2019-04-04

原文来源:The Economist 2019-4-5

The beauty of breadth

Indian politicians are promising more cash for the poor. They should be less selective

Good king wenceslas thought of the poor when the weather turned cold. Election season has the same effect on India’s politicians. With national polls looming in April and May, the two main political parties are competing to shower money on the indigent. The governing Bharatiya Janata Party (bjp) has al- ready started paying benefits to farmers who own less than two hectares (five acres) of land. The Congress party promises cash payments for the poorest 50m households. The new focus on the problem is admirable, but these ideas need rethinking.

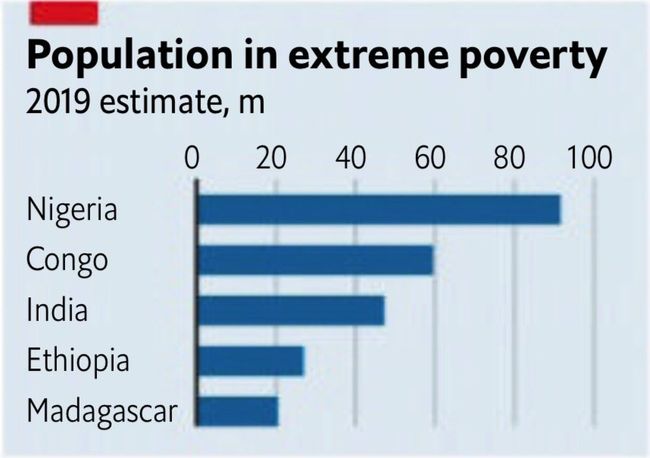

India has about 50m people living in extreme poverty, accord- ing to the World Poverty Clock, an Austrian research project. Many others are severely pinched. Yet India’s safety-net is both immensely complicated, with over 950 centrally funded schemes and subsidies, and stingy. Old people protested in the capital last year, complaining that the central-government pen- sion of 200 rupees ($3) a month has been frozen since 2007. Much of the money spent on welfare never gets to the poor. Numerous subsidies for fertiliser, power, water and so forth are snaffled by better-off farmers or go into officials’ pockets. A large rural employment scheme does mostly reach poor people, since nobody else is prepared to dig ditches all day under the hot sun. But it is expensive to run and prevents participants from doing any other work. A study carried out in Bihar, a poor state, by the World Bank estimated that you could cut poverty at least as much by taking the money for the scheme and dividing it among the entire population, whether poor or not.

It is welcome, then, that the parties are vying to come up with better schemes. And it is especially encouraging that both the bjp and Congress are proposing simply to give people money. Distributing cash is cheaper than handing out jobs or food, and allows poor people to buy whatever they need. As bank accounts spread and India’s biometric id system matures, it should be possible to curb fraud and theft.

Yet the politicians’ plans are ill thought out. Even if the bjp’s bung to farmers manages to get round the problem that many lack clear land titles, it will do nothing for landless labourers, who are often poorer than smallholders. It would have perverse consequences, too, for it would discourage small farmers from getting bigger. Congress’s scheme to pay needy families 6,000 rupees a month is better (see Asia section), but faces the practical and political difficulties involved in targeting the poor.

Targeting welfare is costly and difficult in a country like In- dia. How is the state supposed to identify the poorest 50m households in a country where income and spending are so hard to track? If it looks for signs such as straw roofs, it will almost certainly miss many poor people, especially in the cities. The political economy of targeted schemes is also tricky. In countries with minimal welfare states, schemes with few beneficiaries also have few supporters, and therefore risk being quietly wound down or diminished by inflation. And any formula used to target the bottom 20% is likely to be so opaque that people will never know whether they should have been included or not, so cannot fight for their entitlements. A workfare scheme in Argentina , trabajar, was so well-targeted—75% of its beneficiaries were among the bottom 30%—that it lost political support and was replaced by a benefit with broader appeal. As Amartya Sen, an Indian economist, put it, benefits that go only to the poor often end up being poor benefits.

Two years ago a government report suggest- ed a bold new approach. Instead of a universal basic income—an idea doing the rounds in rich countries—create a nearly universal scheme from which you exclude the richest quarter of the population. They are easier (and therefore cheaper) to spot than the poorest. The report estimated that poverty could be virtually eradicated at a cost of 5% of gdp— just about the same as the combined cost of the existing schemes and subsidies. Transfers to the very poor would be lower under Congress’s plan, but since a broader scheme’s chances of survival are higher, indigent Indians would probably benefit more in the long run.

Binning the hotch-potch of existing schemes and implementing a radical new system would be politically difficult. Yet the broader plan may have a better chance than a targeted scheme, since many of the beneficiaries of the old schemes would get some cash under the new one. And it must be worth a try. The eradication of one of the world’s very worst problems is a prize worth fighting for.

Notes

two main political parties are competing to shower money on the indigent

竞争着去做某事,抢着去做某事;撒钱给穷苦人民

promises cash payments for the poorest 50m households.

最穷的50百万家庭

but these ideas need rethinking.

三思啊

Ex:I still some time to rethink my plan.

Much of the money spent on welfare never gets to the poor

money gets to the poor,都没能到穷人手上

Numerous subsidies for fertiliser, power, water and so forth are snaffled by better-off farmers or go into officials’ pockets

补助;抢先攫取;条件较好的farmer

dig ditches all day under the hot sun

在火辣的太阳下整天干活挖沟渠

the parties are vying to come up with better schemes

vie (with sb) (for sth) (formal) to compete strongly with sb in order to obtain or achieve sth 激烈竞争;争夺 SYNCOMPETE

handing out jobs or food

ˌhand sth↔'out (to sb)

1 to give a number of things to the members of a group 分发某物 SYNDISTRIBUTE

Could you hand these books out, please?

请把这些书发给大家好吗?

—related noun HANDOUT

2 to give advice, a punishment, etc. 提出,给予(建议、惩罚等)

He's always handing out advice to people.

他总是喜欢教训人。

curb fraud and theft.

控制,抑制,限定,约束(不好的事物) SYN CHECK

Yet the politicians’ plans are ill thought out.

carefully/well/badly thought-out planned and organized carefully, well etc:

a carefully thought-out speech

get round the problem

get round something to avoid something that is difficult or causes problems for you:

Most companies manage to get round the restrictions.

needy families

贫穷家庭

faces the practical and political difficulties involved in targeting the poor.

怎么定位和找到这些穷人

Targeting welfare is costly and difficult in a country like India.

等于targeting the poor

straw roofs

草屋顶,很穷

risk being quietly wound down or diminished

wind down

to bring a business, an activity, etc. to an end gradually over a period of time 使(业务、活动等)逐步结束

The government is winding down its nuclear programme.

政府在逐步取消核计划。

a bold new approach

大胆的冒险的

Binning the hotch-potch of existing schemes and implementing a radical new system would be politically difficult.

bin:扔掉,hotchpotch 杂乱无章的一堆东西,大杂烩

The eradication of one of the world’s very worst problems is a prize worth fighting for.

something very important or valuable that is difficult to achieve or obtain 难能可贵的事物;难以争取的重要事物

View

And any formula used to target the bottom 20% is likely to be so opaque that people will never know whether they should have been included or not, so cannot fight for their entitlements.

A workfare scheme in Argentina, trabajar, was so well-targeted—75% of its beneficiaries were among the bottom 30%—that it lost political support and was replaced by a benefit with broader appeal. As Amartya Sen, an Indian economist, put it, benefits that go only to the poor often end up being poor benefits.

Transfers to the very poor would be lower under Congress’s plan, but since a broader scheme’s chances of survival are higher, indigent Indians would probably benefit more in the long run.

Yet the broader plan may have a better chance than a targeted scheme

It is a common sense to help needy people in a developing country. However, how to hand out a nation’s resources is the essence. The straight method is to help the poorest families. But targeting welfare is costly and difficulty in some countries like India. What is more, we should not forget the truth that benefits go only to the poor often end up being poor benefits since every project needs political support. So the author proposed that a broader plan rather than a targeted scheme would be more suitable for India, which means creating a nearly universal scheme from which you exclude the riches quarter of the population. The rich is more easier to spot than the poor.