Joseph Stromberg from Vox.com

A hundred years ago, if you were a pedestrian, crossing the street was simple: You walked across it.

一百年前,过马路这件事再简单不过:径直穿过去。

Today, if there's traffic in the area and you want to follow the law, you need to find a crosswalk. And if there's a traffic light, you need to wait for it to change to green.

如今,当马路上有车经过、并且你打算守法的话,那么你要找到人行横道才能过马路。如果还有信号灯,那你还需要等待绿灯才能通过。

In the 1920s, auto groups redefined who owned the city street.

在上世纪 20 年代,汽车行业重新定义了一件事:谁拥有城市街道。

Fail to do so, and you're committing a crime: jaywalking. In some cities — Los Angeles, for instance — police ticket tens of thousands of pedestrians annually for jaywalking, with fines of up to $250.

如果你不遵守,那你就在犯罪: jaywalking (擅自穿越马路)。在洛杉矶等城市,警察每年对数万行人开出 jaywalking 罚单,罚款最高达 250 美元。

To most people, this seems part of the basic nature of roads. But it's actually the result of an aggressive, forgotten 1920s campaign led by auto groups and manufacturers that redefined who owned the city streets.

对大多数人而言,这已经成为了交通基本原则的一部分。实际上,在上世纪 20 年代,汽车业领导了一场激进的运动,才重新定义了城市道路的所有权。

"In the early days of the automobile, it was drivers' job to avoid you, not your job to avoid them," says Peter Norton, a historian at the University of Virginia and author of Fighting Traffic: The Dawn of the Motor Age in the American City. "But under the new model, streets became a place for cars — and as a pedestrian, it's your fault if you get hit."

“在汽车方兴未艾之时,司机有义务避让行人,而不是行人反过来去避让汽车,”佛吉尼亚大学的 Peter Norton 如是说。他是 Fighting Traffic: The Dawn of the Motor Age in the American City 一书的作者。“然而,在新的交通规则下,道路逐渐被汽车所有。结果就是,如果你被汽车撞了,那就是你的不对。”

One of the keys to this shift was the creation of the crime of jaywalking. Here's a history of how that happened.

促成这种改变的关键之一,就是 jaywalking 这项罪名的设立。让我们来回顾一下这段历史。

When city streets were a public space 曾几何时,城市街道还是公共空间

It's strange to imagine now, but prior to the 1920s, city streets looked dramatically different than they do today. They were considered to be a public space: a place for pedestrians, pushcart vendors, horse-drawn vehicles, streetcars, and children at play.

如今,我们已经很难想象出上世纪 20 年代城市街道的样子;它们与现在的街道看上去有着天壤之别。在那时,街道是个公共空间:行人、手推车商贩、马车穿梭其中,还夹杂着嬉戏玩耍的孩子。

"Pedestrians were walking in the streets anywhere they wanted, whenever they wanted, usually without looking," Norton says. During the 1910s there were few crosswalks painted on the street, and they were generally ignored by pedestrians.

“不论何时何地,人们都可以随意走动,没什么要注意的,” Norton 说。在上世纪初,人行横道十分少见;即使有,行人通常也无视它们。

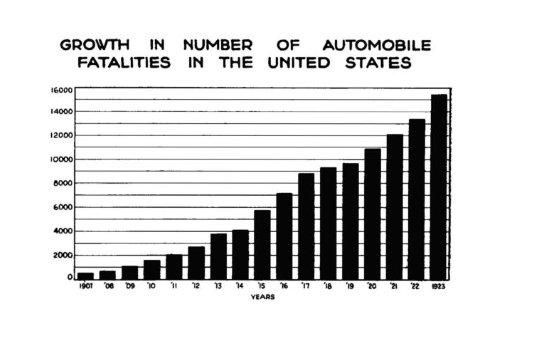

As cars began to spread widely during the 1920s, the consequence of this was predictable: death. Over the first few decades of the century, the number of people killed by cars skyrocketed.

进入 20 年代后,汽车业蓬勃发展,其结果也可想而知:车祸带来的意外死亡。在那几十年中,死于车祸的人数激增。

Those killed were mostly pedestrians, not drivers, and they were disproportionately the elderly and children, who had previously had free rein to play in the streets.

车祸的丧生者绝大多数是行人,而非司机;其中老人与儿童占大多数。在这之前,他们都可以在街道上随意行走、玩耍。

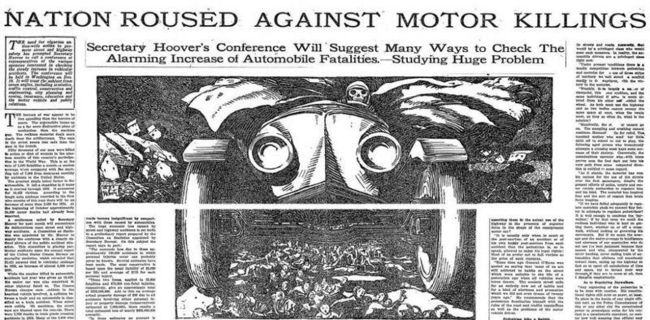

The public response to these deaths, by and large, was outrage. Automobiles were often seen as frivolous playthings, akin to the way we think of yachts today. And on the streets, they were considered violent intruders.

公众对这些车祸感到愤怒。就如同我们今天看待游艇一样,在当时,汽车也被视为一种轻佻的玩物;人们认为它们是粗暴的街道闯入者。

Cities erected prominent memorials for children killed in traffic accidents, and newspapers covered traffic deaths in detail, usually blaming drivers. They also published cartoons demonizing cars, often associating them with the Grim Reaper.

许多城市相继为车祸中丧生的孩子举行了隆重的纪念仪式,新闻媒体也用责备司机的口吻对多起车祸进行了详细报道。一些报纸还刊登了卡通漫画,将汽车妖魔化为死神之车。

Before formal traffic laws were put in place, judges typically ruled that in any collision, the larger vehicle — that is, the car — was to blame. In most pedestrian deaths, drivers were charged with manslaughter regardless of the circumstances of the accident.

在正式的交通法规实施之前,在裁决车祸案件时,法官通常会认定,较大的交通工具——也就是汽车——负有全责。在大多数导致行人死亡的车祸中,不论当时的具体情况如何,汽车司机都被判犯有过失杀人罪。

How cars took over the roads 汽车是如何抢占路权的

As deaths mounted, anti-car activists sought to slow them down. In 1920, Illustrated World wrote, "Every car should be equipped with a device that would hold the speed down to whatever number of miles stipulated for the city in which its owner lived."

车祸导致的死亡越来越多,反汽车运动者开始想方设法降低车速。在 1920 年, Illustrated World 提议,“每辆汽车都应装有限速装置,以限制其车速不得高于车主所在城市的限速。”

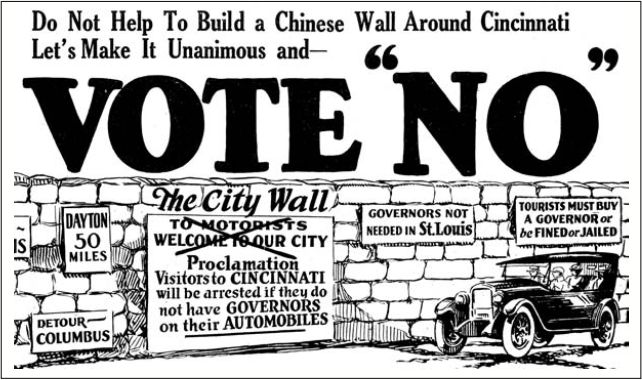

The turning point came in 1923, says Norton, when 42,000 Cincinnati residents signed a petition for a ballot initiative that would require all cars to have a governor limiting them to 25 miles per hour. Local auto dealers were terrified, and sprang into action, sending letters to every car owner in the city and taking out advertisements against the measure.

这一切的转折点, Norton 表示,是 1923 年由 42,000 位辛辛那提居民签署的一份请愿书。在请愿书中,他们发起了一次投票,要将所有汽车的最高速度限制在 25mph (约 40km/h) 。当地的汽车经销商因此慌了阵脚,他们立即行动起来,为市内每位车主寄去信件,并且推出广告,来表达他们反对该提案的立场。

The measure failed. It also galvanized auto groups nationwide, showing them that if they weren't proactive, the potential for automobile sales could be minimized.

辛辛那提居民的提案最终未获通过,但这引起了全国范围内汽车利益团体的警惕:如果他们不主动采取对策,那么全国的汽车销售都可能受到影响。

In response, automakers, dealers, and enthusiast groups worked to legally redefine the street — so that pedestrians, rather than cars, would be restricted.

作为回应,汽车制造商、销售商以及利益团体等联合起来,企图用法律手段重新定义街道,使之服务于汽车——这样一来,反倒是那些行人将受到法律的限制。

This is the traffic law that we're still living with today.

这条规定沿用至今,并未改变。

The idea that pedestrians shouldn't be permitted to walk wherever they liked had been present as far back as 1912, when Kansas City passed the first ordinance requiring them to cross streets at crosswalks. But in the mid-20s, auto groups took up the campaign with vigor, passing laws all over the country.

限制行人任意穿行街道,这一想法早就有人提出了。在 1912 年,堪萨斯城就通过了历史上第一则要求行人使用人行横道过街的法令。不过,直到上世纪 20 年代,由于汽车利益团体积极行动,这类限制行人的法令才得以在全国范围内实施。

Most notably, auto industry groups took control of a series of meetings convened by Herbert Hoover (then secretary of commerce) to create a model traffic law that could be used by cities across the country. Due to their influence, the product of those meetings — the 1928 Model Municipal Traffic Ordinance — was largely based off traffic law in Los Angeles, which had enacted strict pedestrian controls in 1925.

在汽车利益团体的诸多行动中,最值得注意的是他们所操纵的、由时任商务部长 Herbert Hoover 主持召开的一系列会议;会议旨在创立一部模范化的交通法规,并在全国城市进行推广应用。在此之前的 1925 年,洛杉矶就开始实行严格的行人管理,且影响巨大。而这一系列会议的最终产物—— 1928 年《城市交通模范法令》——其实就是借鉴洛杉矶的交通法规而制定的。

"The crucial thing it said was that pedestrians would cross only at crosswalks, and only at right angles," Norton says. "Essentially, this is the traffic law that we're still living with today."

“法令中最关键的一点是,它要求行人必须以直角、使用人行横道通过马路,” Norton 表示。“本质上讲,这条规定沿用至今,并未改变。”

The shaming of jaywalking “ jaywalking ”之耻

Even while passing these laws, however, auto industry groups faced a problem: In Kansas City and elsewhere, no one had followed the rules, and they were rarely enforced by police or judges. To solve it, the industry took up several strategies.

限制行人的诸多法令虽已通过,汽车业者却发现了一个问题:在堪萨斯城等地,根本没人遵守这些法令,执法机构对此几乎不进行监管。于是,他们另辟蹊径。

One was an attempt to shape news coverage of car accidents. The National Automobile Chamber of Commerce, an industry group, established a free wire service for newspapers: Reporters could send in the basic details of a traffic accident and would get in return a complete article to print the next day. These articles, printed widely, shifted the blame for accidents to pedestrians — signaling that following these new laws was important.

其中一个办法就是,他们试图重塑有关车祸的新闻报导。一个名为“国家汽车商会”的利益团体,开通了一条免费新闻热线:记者们只需提供车祸的基本细节,第二天就能获得一份由该团体撰写的车祸完整报导,并进行出版发行。这些报导的共同特点,就是将车祸的责任都推卸到行人一方——这也就暗示公众,遵守新的(有关限制行人的)交通法规十分重要。

Similarly, AAA began sponsoring school safety campaigns and poster contests, crafted around the importance of staying out of the street. Some of the campaigns also ridiculed kids who didn't follow the rules — in 1925, for instance, hundreds of Detroit school children watched the "trial" of a 12-year-old who'd crossed a street unsafely, and, as Norton writes, a jury of his peers sentenced him to clean chalkboards for a week.

美国汽车协会( American Automobile Association )也开始赞助中小学的各类安全宣传活动和海报竞赛,着重强调了随意穿行马路的危害。一些宣传活动甚至公开讥讽那些不守法的孩子——在 1925 年,几百名底特律学生观看了一部特别制作的“审讯”片,在片中,一名 12 岁的儿童未按规定过街,陪审团遂决定“判处”他擦一星期的黑板。

This was also part of the final strategy: shame. In getting pedestrians to follow traffic laws, "the ridicule of their fellow citizens is far more effective than any other means which might be adopted," said E.B. Lefferts, the head of the Automobile Club of Southern California in the 1920s. Norton likens the resulting campaign to the anti-drug messaging of the '80s and '90s, in which drug use was portrayed as not only dangerous but stupid.

这就是汽车利益团体的杀手锏之一:羞耻感。在试图让每个行人遵守新交通法的过程中,“来自身边人的嘲笑,远比其他任何方法都立竿见影,”南加州汽车俱乐部( Automobile Club of Southern California )部长 E.B. Lefferts 在上世纪 20 年代表示。 Norton 表示,与此类似,八九十年代的反毒品运动也利用了人们的羞耻感,将吸毒描绘得不仅危险,而且愚蠢。

Auto campaigners lobbied police to publicly shame transgressors by whistling or shouting at them — and even carrying women back to the sidewalk — instead of quietly reprimanding or fining them. They staged safety campaigns in which actors dressed in 19th-century garb, or as clowns, were hired to cross the street illegally, signifying that the practice was outdated and foolish. In a 1924 New York safety campaign, a clown was marched in front of a slow-moving Model T and rammed repeatedly.

汽车利益团体更是游说警方,在公开场合吹口哨或大声喊叫,以此来羞辱违法者——甚至将违法的女性抬回人行道——而不是像以前那样,低调地斥责或罚款。此外,他们继续推出宣传片,雇佣一些穿着 19 世纪服装的演员或小丑,让他们公开表演非法过街,以此传达这一观点:非法过街是过时、愚蠢的行为。在 1924 年纽约的一次宣传活动中,一个小丑走在一辆缓行的福特 T 型车前,不断被它撞到屁股。

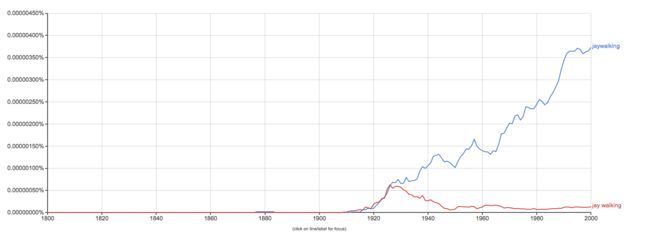

This strategy also explains the name that was given to crossing illegally on foot: jaywalking. During this era, the word "jay" meant something like "rube" or "hick" — a person from the sticks, who didn't know how to behave in a city. So pro-auto groups promoted use of the word "jay walker" as someone who didn't know how to walk in a city, threatening public safety.

这些宣传手法利用了人们的羞耻感,一个新词也应运而生: jaywalking 。当时, jay 的意思类似“乡巴佬”、“土包子”——乡下人进城,不知所措。汽车利益团体则大肆推广“ jay walker ”这一说法,用来描述那些不会依法过街的人,声称他们的行为危害了公共安全。

At first, the term was seen as offensive, even shocking. Pedestrians fired back, calling dangerous driving "jay driving."

起初,公众对此感到震惊,认为这是一种冒犯。许多人对此进行反击,将危险的驾驶行为称为“ jay driving ”。

But jaywalking caught on (and eventually became one word). Safety organizations and police began using it formally, in safety announcements.

然而,“ jaywalking ”还是流行了起来(并最终成为了一个单词);安全组织和警方也开始正式使用这一说法。

Ultimately, both the word jaywalking and the concept that pedestrians shouldn't walk freely on streets became so deeply entrenched that few people know this history. "The campaign was extremely successful," Norton says. "It totally changed the message about what streets are for."

“行人不得随意在马路上走动”这一规则渐渐深入人心,而它背后的这段历史、以及“ jaywalking ”的由来,却鲜为人知。“汽车业者的各种努力最终大获成功,” Norton 说,“‘马路为谁而建’这一问题的答案,也因此而被永远改写。”