原文地址:https://hbctraining.github.io/Intro-to-R/lessons/05_introR-data-wrangling2.html

大神的中文整理版:https://www.jianshu.com/p/14eda97fce0d

本文是我拷贝的原文,加了自己的笔记和练习题答案。

Learning Objectives

- Demonstrate how to subset, merge, and create new datasets from existing data structures in R.

- Export data tables and plots for use outside of the R environment.

Dataframes

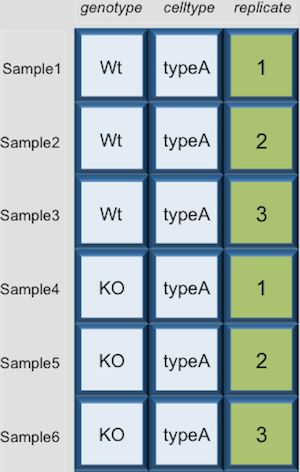

Dataframes (and matrices) have 2 dimensions (rows and columns), so if we want to select some specific data from it we need to specify the “coordinates” we want from it. We use the same square bracket notation but rather than providing a single index, there are two indices required. Within the square bracket, row numbers come first followed by column numbers (and the two are separated by a comma). Let’s explore the metadata dataframe, shown below are the first six samples:

For example:

metadata[1, 1] # element from the first row in the first column of the data frame

metadata[1, 3] # element from the first row in the 3rd column

Now if you only wanted to select based on rows, you would provide the index for the rows and leave the columns index blank. The key here is to include the comma, to let R know that you are accessing a 2-dimensional data structure:

metadata[3, ] # vector containing all elements in the 3rd row

If you were selecting specific columns from the data frame - the rows are left blank:

metadata[ , 3] # vector containing all elements in the 3rd column

Just like with vectors, you can select multiple rows and columns at a time. Within the square brackets, you need to provide a vector of the desired values:

metadata[ , 1:2] # dataframe containing first two columns

metadata[c(1,3,6), ] # dataframe containing first, third and sixth rows

For larger datasets, it can be tricky to remember the column number that corresponds to a particular variable. (Is celltype in column 1 or 2? oh, right… they are in column 1). In some cases, the column number for a variable can change if the script you are using adds or removes columns. It’s therefore often better to use column names to refer to a particular variable, and it makes your code easier to read and your intentions clearer.

metadata[1:3 , "celltype"] # elements of the celltype column corresponding to the first three samples

You can do operations on a particular column, by selecting it using the $ sign. In this case, the entire column is a vector. For instance, to extract all the genotypes from our dataset, we can use:

metadata$genotype

You can use colnames(metadata) or names(metadata) to remind yourself of the column names. We can then supply index values to select specific values from that vector. For example, if we wanted the genotype information for the first five samples in metadata:

colnames(metadata)

metadata$genotype[1:5]

The $ allows you to select a single column by name. To select multiple columns by name, you need to concatenate a vector of strings that correspond to column names:

metadata[, c("genotype", "celltype")]

genotype celltype

sample1 Wt typeA

sample2 Wt typeA

sample3 Wt typeA

sample4 KO typeA

sample5 KO typeA

sample6 KO typeA

sample7 Wt typeB

sample8 Wt typeB

sample9 Wt typeB

sample10 KO typeB

sample11 KO typeB

sample12 KO typeB

While there is no equivalent $ syntax to select a row by name, you can select specific rows using the row names. To remember the names of the rows, you can use the rownames() function:

rownames(metadata)

metadata[c("sample10", "sample12"),]

Selecting using indices with logical operators

With dataframes, similar to vectors, we can use logical vectors for specific columns in the dataframe to select only the rows in a dataframe with TRUE values at the same position or index as in the logical vector. We can then use the logical vector to return all of the rows in a dataframe where those values are TRUE.

idx <- metadata$celltype == "typeA"

metadata[idx, ]

Selecting indices with logical operators using the which() function

As you might have guessed, we can also use the which() function to return the indices for which the logical expression is TRUE. For example, we can find the indices where the celltype is typeA within the metadata dataframe:

idx <- which(metadata$celltype == "typeA")

metadata[idx, ]

Or we could find the indices for the metadata replicates 2 and 3:

idx <- which(metadata$replicate > 1)

metadata[idx, ]

Let’s save this output to a variable:

sub_meta <- metadata[idx, ]

Exercise

Subset the metadata dataframe to return only the rows of data with a genotype of KO.

idx <- which(metadata$genotype == "KO")

sub_meta2 <- metadata[idx, ]

sub_meta2

NOTE: There are easier methods for subsetting dataframes using logical expressions, including the

filter()and thesubset()functions. These functions will return the rows of the dataframe for which the logical expression is TRUE, allowing us to subset the data in a single step. We will explore thefilter()function in more detail in a later lesson.

Lists

Selecting components from a list requires a slightly different notation, even though in theory a list is a vector (that contains multiple data structures). To select a specific component of a list, you need to use double bracket notation [[]]. Let’s use the list1 that we created previously, and index the second component:

list1[[2]]

What do you see printed to the console? Using the double bracket notation is useful for accessing the individual components whilst preserving the original data structure.用双中括号可以保留这一元素原有的数据结构 When creating this list we know we had originally stored a dataframe in the second component. With the class function we can check if that is what we retrieve:

comp2 <- list1[[2]]

class(comp2)

You can also reference what is inside the component by adding and additional bracket. For example, in the first component we have a vector stored.

list1[[1]]

[1] "ecoli" "human" "corn"

Now, if we wanted to reference索引the first element of that vector we would use:

list1[[1]][1]

[1] "ecoli"

You can also do the same for dataframes and matrices, although with larger datasets it is not advisable. Instead, it is better to save the contents of a list component to a variable (as we did above) and further manipulate it. Also, it is important to note that when selecting components we can only access one at a time. To access multiple components of a list, see the note below.

NOTE: Using the single bracket notation also works wth lists. The difference is the class of the information that is retrieved. Using single bracket notation i.e.

list1[1]will return the contents in a list form and not the original data structure用单中括号将不保留原数据结构. The benefit of this notation is that it allows indexing by vectors so you can access multiple components of the list at once.

Exercises

Let’s practice inspecting lists. Create a list named random with the following components: metadata, age, list1, samplegroup, and number.

Print out the values stored in the

samplegroupcomponent.From the

metadatacomponent of the list, extract thecelltypecolumn. From the celltype values select only the last 5 values.

random <- list(metadata,age,list1,samplegroup,number)

random1 <- random[[4]]

random1

random2 <- random[[1]]

random2$celltype

tail(random2$celltype,5)

Assigning names to the components in a list can help identify what each list component contains, as well as, facilitating the extraction of values from list components.

Adding names to components of a list uses the same function as adding names to the columns of a dataframe, names().

Let’s check and see if the list1 has names for the components:

names(list1)

When we created the list we had combined the species vector with a dataframe df and the numbervariable. Let’s assign the original names to the components:

names(list1) <- c("species", "df", "number")

names(list1)

Now that we have named our list components, we can extract components using the $ similar to extracting columns from a dataframe. To obtain a component of a list using the component name, use list_name$component_name:

To extract the df dataframe from the list1 list:

list1$df

Now we have three ways that we could extract a component from a list. Let’s extract the speciesvector from list1:

list1[[1]]

list1[["species"]]

list1$species

Exercise

Let’s practice combining ways to extract data from the data structures we have covered so far:

- Set names for the

randomlist you created in the last exercise. - Extract the third component of the

agevector from therandomlist. - Extract the genotype information from the

metadatadataframe from therandomlist.

random

names(random) <- c("a","b","c","d","e")

random$c

random$a

random$a$genotype

Writing to file

Everything we have done so far has only modified the data in R; the files have remained unchanged. Whenever we want to save our datasets to file, we need to use a write function in R.

To write our matrix to file in comma separated format (.csv), we can use the write.csv function. There are two required arguments: the variable name of the data structure you are exporting, and the path and filename that you are exporting to. By default the delimiter is set, and columns will be separated by a comma:

write.csv(sub_meta, file="data/subset_meta.csv")

Similar to reading in data, there are a wide variety of functions available allowing you to export data in specific formats. Another commonly used function is write.table, which allows you to specify the delimiter you wish to use. 用write.table可以自定义间隔格式This function is commonly used to create tab-delimited files.

NOTE: Sometimes when writing a dataframe with row names to file, the column names will align starting with the row names column. To avoid this, you can include the argument

col.names = NAwhen writing to file to ensure all of the column names line up with the correct column values.

Writing a vector of values to file requires a different function than the functions available for writing dataframes. You can use write() to save a vector of values to file. For example:

write(glengths, file="data/genome_lengths.txt", ncolumns=1)

An R package for data wrangling

The methods presented above are using base R functions for data wrangling. Later we will explore the Tidyverse suite of packages, specifically designed to make data wrangling easier.