4.1 Introduction

4.1.1 The Role of the Parser

There are three general types of parsers for grammars: universal, top-down and bottom-up. Universal parsing methods such as the Cocke-Younger-Kasami algorithm and Earley's algorithm can parse any grammar. These general methods are, however, too inefficient to use in production compilers.

The methods commonly used in compilers can be classified as being either top-down or bottom-up. As implied by their names, top-down methods build parse trees from the top (root) to the bottom (leaves), while bottom-up methods start from the leaves and work their way up to the root. In either case, the input to the parse is scanned from left to right, one symbol at a time.

The most efficient top-down and bottom-up methods work only for subclasses of grammars, but several of these classes, particularly, LL and LR grammars, are expressive enough to describe most of the syntactic constructs in modern programming languages.

4.1.2 Representative Grammars

E represents expressions consisting of terms separated by + signs, T represents terms consisting of factors separated by * signs, and F represents factors that can be either parenthesized expressions or identifiers.

Expression grammar (4.1) belongs to the class of LR grammars that are suitable for bottom-up parsing . This grammar can be adapted to handle additional operators and additional levels of precedence. However, it cannot be used for top-down parsing because it is left-recursive.

The following non-left-recursive variant of the expression grammar (4.1) will be used for top-down parsing:

4.1.3 Syntax Error Handling

Common programming errors can occur at many different levels.

Lexical errors include misspellings of identifiers, keywords, or operators.

Syntactic errors include misplaced semicolons or extra or missing braces; that is, "{" or "}".

Semantic errors include type mismatches between operators and operands.

Logical errors can be anything from incorrect reasoning on the part of the programmer to the use in a C program of the assignment operator = instead of the comparison operator ==. The program containing = may be well formed; however, it may not reflect the programmer's intent.

The error handler in a parser has goals that are simple to state but challenging to realize:

Report the presence of errors clearly and accurately.

Recover from each error quickly enough to detect subsequent errors.

Add minimal overhead to the processing of correct programs.

Fortunately, common errors are simple ones, and a relatively straightforward error-handling mechanism often suffices.

4.1.4 Error-Recovery Strategies

Panic-Mode Recovery: With this method, on discovering an error, the parser discards input symbols one at a time until one of a designated set of synchronizing tokens is found. The synchronizing tokens are usually delimiters, such as semicolon or }, whose role in the source program is clear and unambiguous. While panic-mode correction often skips a considerable amount of input without checking it for additional errors, it has the advantage of simplicity, and, unlike some methods to be considered later, is guaranteed not to go into an infinite loop.

Phrase-Level Recovery: On discovering an error, a parser may perform local correction on the remaining input, that is, it may replace a prefix of the remaining input by some string that allows the parser to continue.

Error Productions: By anticipating common errors that might be encountered, we can augment the grammar for the language at hand with productions that generate the erroneous constructs.

Global Correction: Ideally, we would like a compiler to make as few changes as possible in processing an incorrect input string, There are algorithms for choosing a minimal sequence of changes to obtain a globally least-cost correction. Given an incorrect input string x and grammar G, these algorithms will find a parse tree for a related string y, such that the number of insertions, deletions, and changes of tokens required to transform x into y is as small as possible. Unfortunately, these methods are in general too costly to implement in terms of time and space, so these techniques are currently only of theoretical interest.

4.2 Context-Free Grammars

4.2.3 Derivations

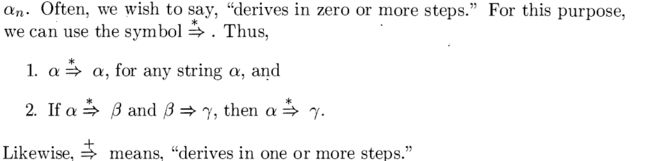

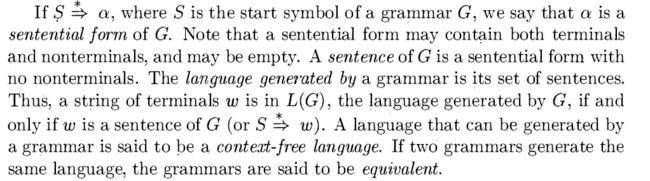

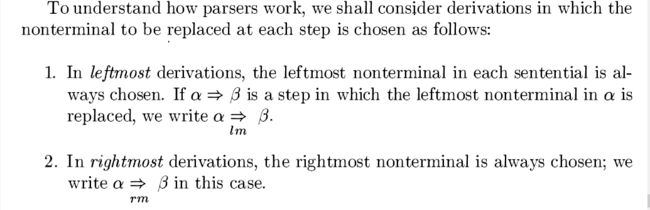

⇒ : derives in one step

Rightmost derivations are sometimes called canonical derivations.

4.2.4 Parse Trees and Derivations

A parse tree is a graphical representation of a derivation that filters out the order in which productions are applied to replace nonterminals. Each interior node of a parse tree represents the application of a production. The interior node is labeled with the nonterminal A in the head of the production; the children of the node are labeled, from left to right, by the symbols in the body of the production by which this A was replaced during the derivation.

4.2.7 Context-Free Grammars Versus Regular Expressions

Every construct that can be described by a regular expression can be described by a grammar, but not vice-versa. Alternatively, every regular language is a context-free language, but not vice-versa.

4.3 Writing a Grammar

4.3.2 Eliminating Ambiguity

- rule

- unambiguous grammar

4.3.3 Elimination of Left Recursion

A grammar is left recursive if it has a nonterminal A such that there is a derivation A ⇒+ Aα for some string α. Top-down parsing methods cannot handle left-recursive grammars, so a transformation is needed to eliminate left recursion.

Immediate left recursion: A → Aα.

Immediate left recursion can be eliminated by the following technique, which works for any number of A-productions. First, group the productions as

A → Aα1 | Aα2 | ··· | Aαm | β1 | β2 | ··· | βn

where no βi begins with an A. Then, replace the A-productions by

A → β1A' | β2A' | ··· | βnA'

A' → α1A' | α2A' | ··· | αmA' | ε

The nonterminal A generates the same strings as before but is no longer left recursive.

General case: left recursion involving derivations of two or more steps.

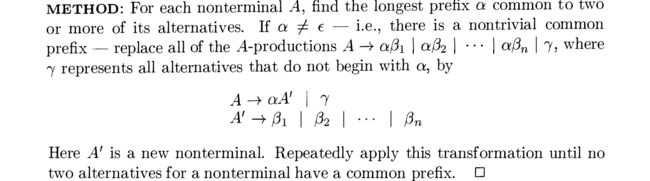

4.3.4 Left Factoring

Left factoring is a grammar transformation that is useful for producing a grammar suitable for predictive, or top-down, parsing. When the choice between two alternative A-productions is note clear, we may be able to rewrite the productions to defer the decision until enough of the input has been seen that we can make the right choice.