关于上海龙美术馆安东尼·葛姆雷的11个小短文

THE SEARCH FOR SPIRITUALITY IN COLD IRON;

11 short texts about Antony Gormley at the Long Museum, Shanghai.

1

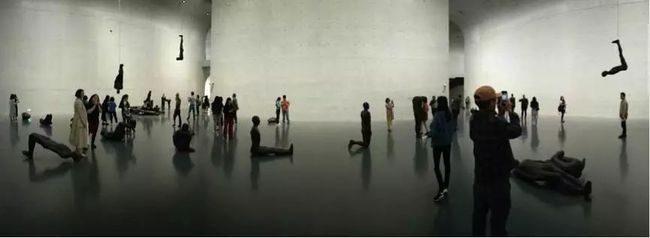

To enter the front gallery of the Long Museum for the first time feels like walking into a minimalistic cathedral. The raw concrete walls ascend in a straight line, forcing my curious gaze upwards, before softly changing angles when almost out of reach, creating a ceiling similar in shape to the arched window that so generously guides the daylight onto Antony Gormley’s cast iron sculptures below. Even the murmurs from the hundred or so people that are here to view the exhibition have an almost religious ring to it, like an abstract form of chant previously unknown to me. And when we move our focus to what we are really here to experience, the already renowned works of art, the signs that we might be in for something a bit more than at least I had expected, just keeps appearing, as one of the first figures that attract our attention is a man on his knees with his face to the ground.

Is he praying, my wife asks me with a whisper.

I am not sure, I reply as I take her hand in mine.

I am really not sure.

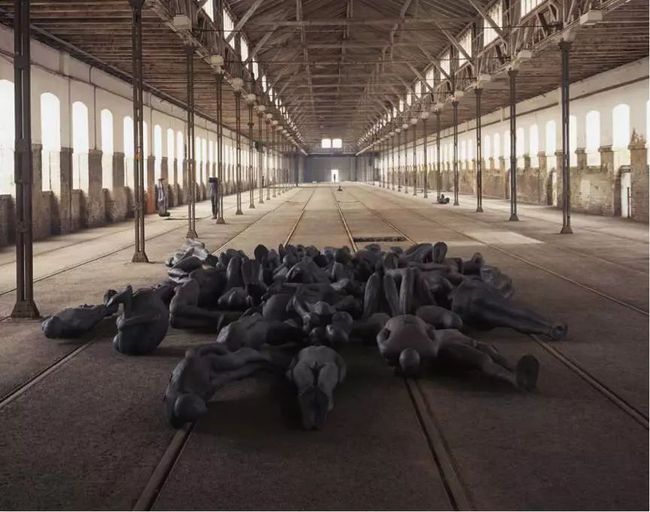

Critical Mass II, 1995, detail. Photo: Stein-Arne With.

2

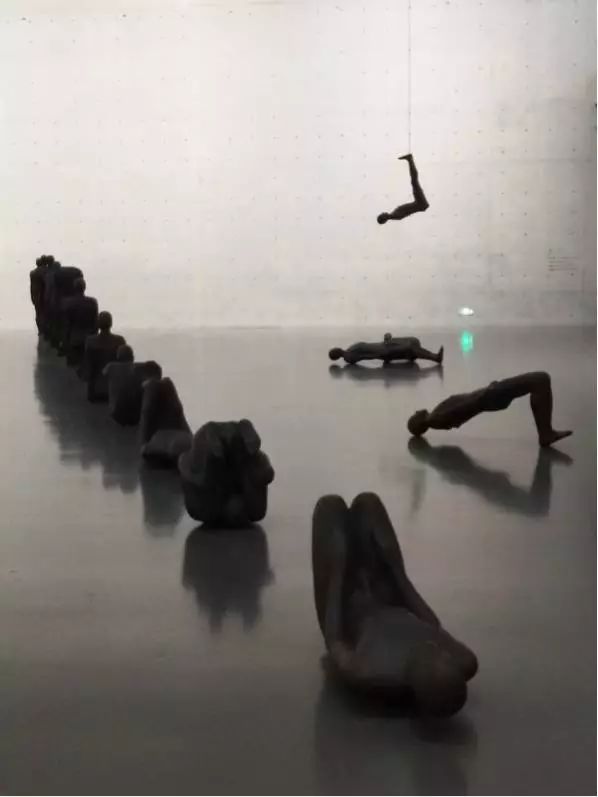

While holding hands we slowly advance towards the middle of the room. The life-size figures of naked men that make up the piece Critical Mass II continue to pose before us. Some of the sculptures made in the image of the artist himself are installed in a linear progression, ground-hugging, crouching, foetal, squatting, sitting, kneeling, standing, mourning and a final instability - an ascent of man ranging through the complex syntax of the body, while others are suspended in mid fall or scattered on the floor, individually, in pairs, or grouped together in a pile in the way that has become a regular display of these bodies throughout their lifetime.

What do you think, I ask my wife.

I am not sure, she answers, before letting go of my hand.

I am not sure what it all means, she continues, looking up at me.

Can you explain it to me?

3

In what can only be described as an imminent bodily response to my wife’s request, I take a few steps forward. I stop beside a body lying on his back, focusing on his virtually featureless face, and in the next ten seconds I try to orientate myself within the small flood of information that was just released inside my head.

Where should I begin?

To be honest I have not always been that fond of Gormley’s work. In most cases I have felt that something essential is actually missing from it, and despite his rather personal and intimate way of creating many of his sculptures, I have never found them to be very accessible. When confronted with Gormley’s work in the past it has felt a bit cold and out of reach, lacking any form of intimacy, something that works fine when dealing with topics like the Holocaust, but that in the long run, in the context of being art, becomes very tedious, repetitive and in fact superficial, as the work will always be about them, and not at all connected to the ones that are actually there experiencing it. Of course there are exceptions, like with Another Time (1999-2013) and his beautiful and fragile Still I (1994), but in the past, before visiting the Long Museum on this cloudy spring day, I was always under the impression that “one swallow doesn't make a summer”. I might have been wrong.

Still I (1994), photo from Antony Gormley’s website.

4

The first time Antony Gormley exhibited the installation now directly in front of us was in 1995, after creating the cast iron sculptures that over time has become one of his best-known pieces in direct response to the Remise, an old tram storage station in Vienna. The artist’s initial idea for this work was to try and isolate basic body positions, then to test them by laying them in different arrangements. In the end only 11 of the body forms were displayed in the way they were cast (i.e. in a realistic position). All the rest were tumbled, literally dumped from the back of a truck, giving them contradictory and sometimes absurd connotations. The original installation was made up of 5 casts of the 12 already mentioned positions, and it is these 60 body forms that are now the core of the Still Moving exhibition, the first major presentation of Gormley’s work in China.

Critical Mass, 1995, detail from when originally displayed. Photo from the Antony Gormley website.

5

In physics, the term Critical Mass is the minimum amount of a substance needed to start a nuclear chain reaction. When applied to social issues, Critical Mass usually means the necessary level of density within a collective that allows for something transformative to happen. Within this particular work of art, the bodies appear to somehow have descended from their regular surroundings, and while the first impression under “normal” circumstances might have been that some kind of trauma had occurred, perhaps an act of violence perpetrated towards the masses, such as terrorism or genocide, viewing the sculptures here in the Long Museum makes me wonder if spirituality actually can be found in cold iron, contrary to prior belief.

Critical Mass II, 1995, detail. Photo: Stein-Arne With.

6

Can you please explain it to me?

Her repeated question turns me around.

Yes, of course, I answer, kissing her on the mouth, quickly, in order for her not to get too embarrassed by my public display of affections. I then crouch down beside the faceless figure in order to get a closer look at the texture of its iron body. Cast from the outside of a plaster mould, all the imperfections on the surface of the mould are transferred onto the finished work. The loose pieces in the sand mould are also integrated into the surface, as are both the flash lines that exist between them, and the out-runners of the metal-pouring. The solidity and weight of each piece is an active feature of the work; the density of each iron body being ten times that of a human body of the same size, giving it a stability that its relatively vulnerable positioning might not suggest. Its scent is close to that of a rusted ship, or maybe more accurately; to the submarine I got to visit when only a seven year old boy.

Critical Mass II, 1995, detail. Photo: Stein-Arne With.

7

While touching his cold iron chest with my index finger I start talking. But instead of communicating the information that has been racing through my mind in the last couple of minutes, the words I choose to share with my wife are very different than what I thought they would be, and rightly so.

Maybe it is the design of the gallery that at last allows the piece to show its flexibility, maybe it is the figures’ placement that allows the meaning of the work to shift from where it has been trapped for more than 20 years, but what we now see before us is not about the Holocaust, it is not about “the victims of the twentieth century”, it is not about “indexical body impressions that freeze time”, or any other abstracted explanation that increases the gap between the artist (hence the art) and the beholder.

This is plain and simple about you and me.

It is about my neighbor and your neighbor.

It is about that guy you work with.

It is about the woman you sit next to on the bus or on the subway.

It is about all of us, regardless of what country we are from, what color our skin is or which language we speak.

And contrary to what Gormley himself have said: This piece is also about moments in time, at least when exhibited in this museum, not just about “being” in the bigger sense.

At the same time the iron figures does not seem to be just about the body, but also about the soul; the emotions that being human brings to us when every unnecessary detail is stripped away, the unrestricted reality that we all, each and every one of us, have to face every single day of every single month of every single year of our lives. This is about life as first-hand experience, about using the conditions of existence as a kind of test site for asking questions regarding what it means to be alive, what it means to be conscious.

And that is, from where I am standing, what art first and foremost should be about.

Critical Mass II, 1995, detail. Photo: Stein-Arne With.

8

Curious if the “praying man” is still praying I once again close in on him, and while looking at the kneeling figure from a different angle, with the pile of 18 or so bodies just behind him, a question that was initially intended to be no more than a thought slips out between my lips.

Might the artist finally be showing us himself?

While staying in India in the early 1970s, Antony Gormley was faced with the question we all at some point are confronted with; what should he do with his life? Should he select the spiritual life, which meant to carry on with his Buddhist studies and eventually become a fully integrated monk and meditator within the Theravadā tradition, or should he choose another path. In the end he felt that it was his responsibility to try to go back to Britain to fulfill some kind of creative role, and maybe bring what insight and knowledge he had acquired in India back into that stream of development.

Part of that insight was an “acceptance of the body as our first home”, something we quite clearly can detect in the figure on the floor in front of me, as his body is without a doubt his only protection against the world outside him, against the consequences linked to the choices he eventually ended up making.

Critical Mass II, 1995, detail. Photo: Stein-Arne With.

9

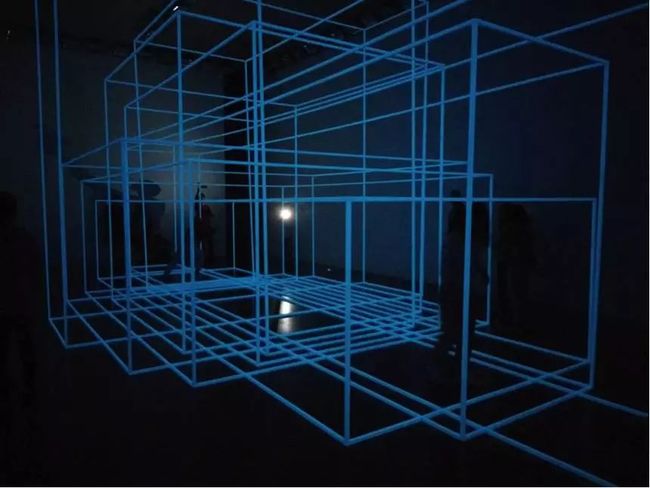

Adapted from his Still Being show in Brazil in 2012, Still Moving also includes other works than Critical Mass II. Passage II (2016) is a new work modeled on a standing human form, where the visitor is able to take part in a journey, a stroll into darkness, or rather towards the light that meets them on the other side of the 15.5-metre long steel tunnel. Breathing Room IV (2012) is a series of interlinking open rectangular structures made out of nesting photo-luminescent space frames that will glow in the ten minutes of darkness that surrounds it, before the darkness is interrupted by 40 seconds of blinding light. The idea is to invite the viewer to “look at it as an object and engage with it as a subject, providing both a soothing and confrontational experience”, without it actually getting close to being much more than a photo opportunity for the selfie-hunting fraction of the public.

Breathing Room IV, 2012, (including selfie-hunting individuals). Photo: Stein-Arne With.

10

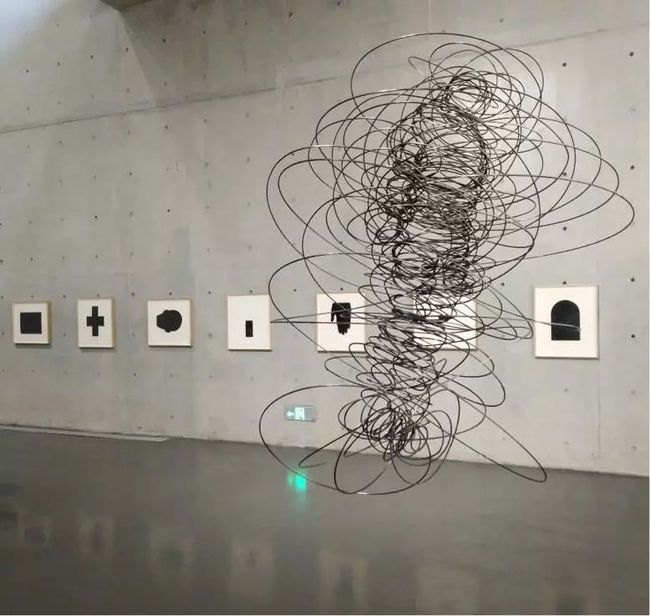

Four additional suspended sculptures (2008-2012) follows. "What I try to show is the space where the body was, not to represent the body itself", Gormley told Nicholas Wroe of The Guardian in 2005, and those words explain these pieces to the fullest, as this is all about using what in technical terms is called the negative space. Created as “drawings in mid air” the sculptures are efficiently mixed together with a wide selection of drawings and prints on paper. As drawing has always been the fruitful start to Gormley’s projects, no matter the size of the project, these works offer a valuable understanding of the artist’s process, although they are more like sketches and ideas, a starting point (that also include a link to the symbol use of Antoni Tàpies), rather than “drawings and prints that chart the intimate movements of the hand and impressions of the body that result from an interaction between the behavior and intuition”, as the exhibition pamphlet so pompously puts it.

Feeling Material XXXVI, 2008. Photo: Stein-Arne With.

11

After hours and hours of non-stop dialogue with our surroundings, with each other, as well as the constant inner dialogue with ourselves, we decide that it is time to leave both the Long Museum as well as Antony Gormley’s work behind. Somewhere on the outside of the thick concrete walls a good meal awaits, maybe even a glass of red wine, but in order to depart the somewhat futuristic world designed by Atelier Deshaus and get back out into the real world, we must first return to the room where we entered this minimalistic cathedral, then turn the entryway into an exit.

On the way out I stop to have one last look at the iron sculptures of Critical Mass II, and as I find a surprisingly solitary spot close to one of the walls, a new set of reflections and information comes running like impulsive children onto the cerebral playground that was made relatively vacant about an hour earlier. After then sharing my thoughts about the exhibition in a somewhat passionate manner, looking at the pieces of art now brings a sudden calm to me, a silence that despite the noise of the surroundings spreads out like a delicate mist, in the end reaching from the floor, all the way up to the arched ceiling above.

Critical Mass II, 1995, detail. Photo: Stein-Arne With.

Wherever they are shown, the sculptures of Antony Gormley will evoke contradictory readings and emotions from the viewer depending upon which way the viewers are orientated. That is the way it is with all art, even the pieces that, when it comes down to it, is not that good. Depending on its quality a piece of art can leave a void, a black hole that will never leave you with anything other than emptiness, or it can work as a catalyst for a process of understanding, a kind of empathy, a process of engagement that in itself can be an entryway to new thoughts and emotions. In the most extreme cases you will have experienced something that will have made you a better and more knowledgeable person when you leave the exhibition space, than when you walked in. In those rare moments the beholder gets to experience a connection between the piece and its surroundings that lifts art itself up to a higher level. Personally, I have only had that kind of significant encounter through art twice before, when Olafur Eliasson showed the Weather Project in the Turbine Hall of the Tate Modern, and when walking into the Rothko room in the same museum. When visiting Still Moving it doesn't quite reach that highest level, primarily because of reasons that I will discuss at a later stage, but it certainly comes close. After more than 20 years being exhibited in various cities in various countries all around the world, it is like the cast iron bodies once again have found a place they can call home, a place where they truly belong. And what better place for an artist searching for spiritual experience through objects to find shelter for the most genuine representation of his body and soul than in a beautiful museum in the part of the world where Buddha roamed the earth, what better way for a skeptic to be made aware of the presence of spirituality, even in cold iron, than through the near perfect synergy of art and architecture that this exhibition so graciously offers us.

Art can be the way that life expresses itself, and this time it has.

Thank you Antony.

Photo: Stein-Arne With.

THE END

The exhibition STILL MOVING will be open until the 26th of November. Go there if you can, with an open heart, open eyes and an open mind.

In the process of writing this text I have used the following sources to gather information:

1 British sculptor Antony Gormley showing at Shanghai’s Long Museum, but admits it should be Chinese artists getting the chance | South China Morning Post.

2 Critical mass definition and meaning | Collins English Dictionary.

3 Profile: Antony Gormley | Art and design | The Guardian

4 Resurgence • Article - An Interview with Antony Gormley

5 http://www.antonygormley.com/

6 Still Moving exhibition pamphlet