A Hands-On Tutorial for Zero-Knowledge Proofs: Part II

A Hands-On Tutorial for Zero-Knowledge Proofs: Part II

In the previous post we developed the witness for our proof. Simply put - it is a piece of data that the prover will claim it has, and the verifier will ask queries about. In this process will develop the machinery required to force the prover to be - if not honest, then at least consistent.

Hopefully, our protocol will be such that the prover cannot make a false claim and be consistent about it.

Where were we?

Recall that in our setting, the prover claims knowledge of a (supposedly secret) satisfying assignment to a known Partition Problem instance. The protocol we developed so far was this:

- The verifier chooses a random value ii.

- According to the value of ii, the verifier asks for two values from the witness (usually two consecutive values, but sometimes the first and the last).

(check the previous post for exact details).

Indeed, if the prover is honest in its answers, and doesn’t cheat or make mistakes, then after enough queries - the verifier should be convinced. But hold on, if the prover is honest - why have all this elaborate game of questions and answers? the verifier can just take the prover’s word for it, and everyone’ll go home early.

But the prover may be a liar!!!

The entire raison d’être of ZK proofs is that we assume that the prover may be dishonest. So, assuming that the prover knows the protocol that the verifier is using - it can simply send such queries that will satisfy the verifier. If the verifier asks for two consecutive values, the prover will provide some two random numbers such that their absolute value matches the verifier’s expectations (i.e., the corresponding value in the problem instance), and if it asks for the first and last element, the prover will just send some random number twice.

The Commitments

What we need here is a mechanism that will:

- Force the prover to write down all of the values of pp before the verifier asks about them.

- When asked, force the prover to return the required values from this previously written list.

This is a concept known in the world of cryptography as a commitment scheme.

In our case, we’re going to work with a 40 year-old commitment scheme, a Merkle Tree. It is a simple and brilliant idea.

A Merkle Tree is just a full binary tree, where each node is assigned a string:

- The leaves contain hashes (we’ll use Sha256) of the data we’d like to commit to.

- Every internal node in the tree is assigned with a string that is a hash of its two children’s strings.

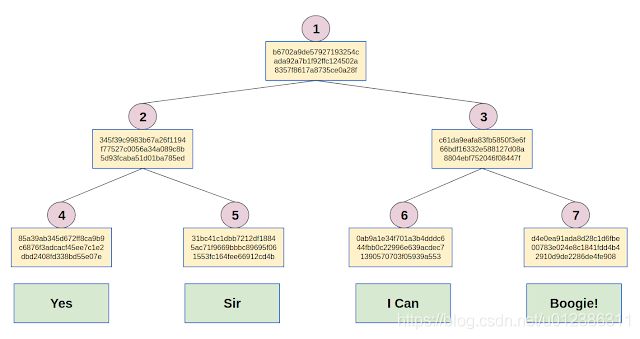

Suppose we want to commit to this list of four strings: [“Yes”, “Sir”, “I Can”, “Boogie!”].

The Merkle tree will look something like this:

So node 4 is assigned the hash of the word “Yes”, node 5 is assigned the hash of the word “Sir”, and so on.

Also, every node 0<i<40

The string assigned to the root of the tree (i.e. node #1) is referred to as the commitment.

That is because even the slightest change in the underlying data causes the root to change drastically.

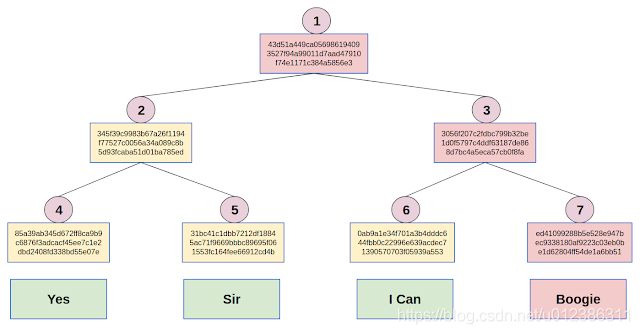

Here’s what happens if we omit the exclamation mark from the word “Boogie” (the affected nodes are marked in red):

An even cooler property of Merkle Trees, is that one can prove that a certain string belongs to the underlying data, without exposing the entire data.

Authentication Paths

Suppose I would like to commit to the title of a 1977 song by the Spanish vocal duo Baccara. The title itself is kept a secret (!), but you can ask me about one of the words in the title (well, I put “I” and “Can” in the same leaf… but let’s ignore this fine point).

To prove that I won’t switch songs half way through our game, I send you the hash from the root node of a Merkle Tree I created.

You now ask me what is the second word in the title, to which I reply “Sir”.

To prove that this answer is consistent with the hash I sent you before, I also send you the hashes of nodes 4 and 3. This is called the authentication path of node 5 (which contains the second word from the title).

You can now check that I’m not lying by:

- Computing the hash of node 5 yourself (by hashing the word “Sir”).

- Using that and the hash I gave you of node 4 to compute the hash of node 2.

- Using that and the hash I gave you of node 3 to compute the hash of the root node.

- Compare the hash you computed with the one I originally sent you, if they match, it means that I didn’t switch song in between the time I sent you the initial commitment, and the time I answered you query about the second word in the title.

It is widely believed that given the Sha256 hash of some string S0S0, it is infeasible to find another string S1≠S0S1≠S0 that has an identical Sha256 hash. This belief means that indeed one could not have changed the underlying data of a Merkle Tree without changing the root node’s hash, and thus Merkle Trees can be used as commitment schemes.

Let’s See Some Code

Recall that we need this machinery in order to commit to a list of numbers which we dubbed “the witness”, and referred to as pp in the previous post.

So we need a simple class with a constructor that gets a list of numbers as input, constructs the necessary Merkle Tree, and allows the user to get the root’s hash, and obtain authentication paths for the numbers in the underlying list.

We’ll also throw in a function that verifies authentication paths, this function is independent from the class, as this can be done simply by hashing.

Here’s a somewhat naive implementation of a Merkle Tree:

import hashlib

from math import log2, ceil

def hash_string(s):

return hashlib.sha256(s.encode()).hexdigest()

class MerkleTree:

"""

A naive Merkle tree implementation using SHA256

"""

def __init__(self, data):

self.data = data

next_pow_of_2 = int(2**ceil(log2(len(data))))

self.data.extend([0] * (next_pow_of_2 - len(data)))

self.tree = ["" for x in self.data] + \

[hash_string(str(x)) for x in self.data]

for i in range(len(self.data) - 1, 0, -1):

self.tree[i] = hash_string(self.tree[i * 2] + self.tree[i * 2 + 1])

def get_root(self):

return self.tree[1]

def get_val_and_path(self, id):

val = self.data[id]

auth_path = []

id = id + len(self.data)

while id > 1:

auth_path += [self.tree[id ^ 1]]

id = id // 2

return val, auth_path

def verify_merkle_path(root, data_size, value_id, value, path):

cur = hash_string(str(value))

tree_node_id = value_id + int(2**ceil(log2(data_size)))

for sibling in path:

assert tree_node_id > 1

if tree_node_id % 2 == 0:

cur = hash_string(cur + sibling)

else:

cur = hash_string(sibling + cur)

tree_node_id = tree_node_id // 2

assert tree_node_id == 1

return root == cur

A few things to note:

- It being a binary tree, we extend the underlying data to the next power of 2 (by padding with 0s) for it to match the number of leaves of a full binary tree.

- We store the root of the tree at index 1 and not 0, and its children at 2 and 3 and so on. This is just so that the indexing will be convenient, and the children of node ii will always be 2i2i and 2i+12i+1.

- This is far from optimal, because for our purposes (a blog post) clarity and brevity are more important.

What About Zero Knowledge???

An observant reader will point out that when we provide the authentication path for node 5, we provide the hash of node 4.

A snooping verifier may try hashing various words from the titles of songs of the Spanish vocal duo Baccara, and when it gets the hash we sent it as “the hash of node 4”, it will have found out a leaf of the tree that we never intended to expose!

In the next post in the series, we’ll deal with the ZK issue, using a simple but effective trick to get a Zero Knowledge Merkle Tree.

Also, we’ll hopefully tie everything together to get the proof we originally wanted!

Part III

原文:http://www.shirpeled.com/2018/10/a-hands-on-tutorial-for-zero-knowledge.html