作者:Paul R. Niven & Ben Lamorte

出版社:Wiley

副标题:Driving Focus, Alignment, and Engagement with OKRs

发行时间:2016年9月6日

来源:下载的 pdf 版本

Goodreads:3.68(26 Ratings)

豆瓣:7.7(77人评价)

概要

可以算是一本 OKRs 的实践指南,非常适合作为手册带在身边,全书结构清晰,观点论证严谨,实施介绍的时候图文并茂,一步一步的介绍 OKRs 的发展历史、基本原则、实施指南、案例分析,非常适合对 OKRs 管理不甚了解的读者

书的结构:

Objectives and Key Results is composed of seven chapters. The first six will lead you through an OKRs implementation in more or less chronological order, while the final chapter showcases the work of a number of global organizations currently benefiting from OKRs.

一个7章,前六章按顺序介绍 OKRs 的实施步骤,最后一章介绍了一些案例

每一章都围绕一个主题:

Chapter 1: Introduction to OKRs(历史、基本概念介绍)

Chapter 2: Preparing for Your OKRs Journey(为什么?如何开始?)

Chapter 3: Creating Effective OKRs(如何具体操作)

Chapter 4: Connecting OKRs to Drive Alignment(如何整体运作)

Chapter 5: Managing with OKRs(早会、中期check-in、季度Review)

Chapter 6: Making OKRs Sustainable(如何可持续的运用)

Chapter 7: Case Studies in OKRs Use(案例参考)

作者介绍

Paul R. Niven 是一位管理类畅销书作者,Ben Lamorte 是一位 OKRs 培训咨询师,两人合开了一个培训公司,现在已经开始有中国业务了

作者撰写的初衷:

As we write this, the OKRs field is still relatively nascent in terms of standard practices and proven procedures. It is an emerging discipline, and while implementations are growing by the day, and consultants and software providers are coming forward in attempts to plug knowledge gaps, no definitive how-to guide exists for organizations anxious to implement OKRs without falling prey to potential pitfalls that can derail this or any change effort. This book is our answer to that challenge. It was written to fill the void that currently exists between knowledge and practice. Organizations wishing to reap the benefits of OKRs must first be made aware of—and properly equipped to overcome—the challenges associated with an undertaking of this magnitude. Based on our global consulting experience with OKRs as well as the extensive research we’ve conducted, these pages will act as your comprehensive guide through the entire OKRs terrain.We’re confident the tools and techniques profiled in this book will propel the success of those currently engaged with OKRs and compel more executives to launch OKRs programs in their own organizations.

个人观点

自己因为对目标管理和 OKRs 一直比较关注,所以阅读这本书,终于通过阅读了解了 OKRs 的发展历史,了解到了中间的关键性人物 Andy Grove,Intel 的创始人之一,标记了他的《High Output Management》,后续会看一下

除了 Andy Grove 的《High Output Management》,另一本彼得德鲁克的经典作品《The Practice of Management》也被多次提到,彼得德鲁克一辈子写过30多本书,我自己标记了有2-3本,后面有时间也会看一下

在目标设定的时候,可以允许有非常高的标准,然后考核其完成的比例,这会带动每个人的 Ambition,我觉得这是 OKRs 最大的意义所在,另一方面,对于个别没有 Ambition 的员工,需要想办法调动起来 Ambition,对于一潭死水的公司,如果要运用起来 OKRs,感觉是不大可能的

原来 OKRs 是以季度为周期的,觉得这个周期的设置,确实比年度更有效率,在现如今发展如此之快的世界

摘录

As we write this, the OKRs field is still relatively nascent in terms of standard practices and proven procedures. It is an emerging discipline, and while implementations are growing by the day, and consultants and software providers are coming forward in attempts to plug knowledge gaps, no definitive how-to guide exists for organizations anxious to implement OKRs without falling prey to potential pitfalls that can derail this or any change effort. This book is our answer to that challenge. It was written to fill the void that currently exists between knowledge and practice. Organizations wishing to reap the benefits of OKRs must first be made aware of—and properly equipped to overcome—the challenges associated with an undertaking of this magnitude. Based on our global consulting experience with OKRs as well as the extensive research we’ve conducted, these pages will act as your comprehensive guide through the entire OKRs terrain.We’re confident the tools and techniques profiled in this book will propel the success of those currently engaged with OKRs and compel more executives to launch OKRs programs in their own organizations.

“When you go for a hike with your family, it’s fine to just walk and enjoy the scenery, but when you’re at work you need to be crystal clear about the destination. Otherwise you’re wasting your time and the time of everyone who works with you.”

Ben was approached by an organization to assist them with a KPI (key performance indicators) project. He accepted the assignment and found himself eagerly awaiting the strategy document that was to be supplied by the company’s CEO. When it arrived, Ben felt overwhelmed. The strategy slide decks and documents were stuffed with ideas and good intentions, but the materials contained a confusing mix of key pillars (corporate priorities), core values, and business metrics. Ben struggled with how to approach the project, and it wasn’t until arriving at his hotel room the night before meeting with the CEO and CFO that he recalled the advice of Jeff Walker. With that in mind, Ben condensed the strategy document into a single page, translating the key pillars into objectives, and assigning key results to each. The next day, he used this organizing framework of OKRs to share his understanding of the organization’s strategy. After his overview, the executives fell quiet and asked for a moment of privacy. Ben left the room convinced he had misinterpreted the strategy and would quickly be dispatched to the airport for the next plane home. Two minutes in the hallway felt like two hours, but when he was summoned back into the room he was relieved to see a smile on the face of the CEO, who said: “We want you to help us create this type of document for every business unit and department in the company!” After helping close to 50 teams at the company draft and refine their OKRs, and later witnessing their success with the method, Ben knew he had found his calling. Hundreds of hours coaching teams and managers later, here we are.

While we think of the model as relatively new—most of us would pin its origination to Google’s adoption in the 1990s—it is actually the result of a successive number of frameworks, approaches, and philosophies whose lineage we can track back well over a hundred years. At the turn of the twentieth century, organizations were much enamored with the work of Frederick Winslow Taylor, a pioneer in the nascent field of Scientific Management. Taylor was among the first to apply scientific rigor to the field of management, demonstrating how such an approach could vastly improve both efficiency and productivity.

In another development, in the 1920s, researchers discovered what would later be termed “The Hawthorne Effect.” At a factory (Hawthorne Works) outside of Chicago, investigators examined the impact of light on employee performance. The studies suggested that productivity improved when lighting increased. However, it was later determined the changes were most likely the result of increased motivation due to interest being shown to employees. While these and many other advancements were casting a light on how companies could enhance productivity through monitoring discrete activities, for the most part employees themselves were an afterthought. That all changed, however, with the work of Peter Drucker.

Considered by most people (ourselves included) to be the father of management thinking, Peter Drucker set the standard for management philosophy and the theoretical foundations of the modern business corporation. Many of his more than 30 books are considered classics in the field. It is one book, his 1954 release, The Practice of Management, which is of particular significance to those of us interested in OKRs. In the text, Drucker tells the story of three stonecutters who were asked what they were doing. “I am making a living” was the response of the first cutter. The second continued hammering as he answered, “I am doing the best job of stonecutting in the entire country.” Finally, the third answered confidently, “I am building a cathedral.” The third person is clearly connected to an overall aspirational vision, while the first is focused almost exclusively on providing a fair day’s work for a fair day’s pay. Drucker’s primary concern was with the second stonecutter, the individual focused on functional expertise, in this case being the best stonecutter in the county. Of course, exceptional workmanship is something to be esteemed and will always be important in carrying out any task, but it must be related to the overall goals of the business.

Drucker feared that in many instances, modern managers were not

measuring performance by its contribution to the company, but by their

own criteria of professional success. He writes, “This danger will be greatly

intensified by the technological changes now underway. The number of

highly educated specialists working in the business enterprise is bound to

increase tremendously . . . the new technology will demand closer coordination

between specialists.” Did we mention he wrote this in 1954! Prescient

as always, Drucker recognized the surge in specialized roles that were to

become the hallmark of the modern corporation, and sensed immediately the

danger that change posed should these specialists be focused on individual

achievement rather than the goals of the enterprise.

In response to this challenge, Drucker proposed a system termed management by objectives, or MBO. He introduces the framework this way:

Each manager, from the “big boss” down to the production foreman or the chief clerk, needs clearly spelled-out objectives. These objectives should lay out what performance the man’s own managerial unit is supposed to produce. They should lay out what contribution he and his unit are expected to make to help other units obtain their objectives. Finally, they should spell out what contribution the manager can expect from other units toward the attainment of his own objectives. . . . These objectives should always derive from the goals of the business.

Readers will forgive Drucker’s exclusive use of the masculine pronouns; again, he was writing this in the 1950s. He went on to suggest that objectives be keyed to both short- and long-range considerations and that they contain both tangible business goals and intangible objectives for organizational development, worker performance, attitude, and public responsibility This last point is yet another example of Drucker’s considerable foresight. It would be another four decades before the inclusion of intangible “assets” was formally included in a corporate performance management system (the Balanced Scorecard).

Already somewhat of a renowned management guru, Drucker’s words carried significant weight in the boardrooms of corporate America and thus resonated with executives, who then raced to create MBO systems within their firms. Unfortunately, as is often the case with any type of managerial or organizational change intervention, implementations varied widely in form, often straying far afield from Drucker’s original intentions for the model. Perhaps the biggest mistake committed by firms eager to gain the benefits offered by MBOs was transforming what was originally envisioned as a highly participative event into a top-down bureaucratic exercise in which senior managers shoved objectives down into the corporation with little regard of how they would be executed. Many also damaged the integrity of the model by making it a static exercise, often setting objectives on an annual basis, despite the fact that even 50 years ago businesses faced pressure to react quickly to market and environmental changes. But, rather than adopt a more frequent cadence, when it came to objective setting most companies chose the “Set it and forget it” pattern we so often see in organizations to this day.

Drucker’s expectation was that organizations would use MBOs to foster cross-functional cooperation, spur individual innovation, and ensure all employees had a line of sight to overall goals. In practice, that rarely occurred and eventually MBOs became the subject of substantial criticisms. However, those with keen business acumen saw the underlying power of Drucker’s words and recognized the value inherent in the process. Enter Andy Grove.

A Silicon Valley legend, Andy Grove served as CEO of Intel Corporation from 1987 to 1998 and shepherded the company through its remarkable transformation from a manufacturer of memory chips into the planet’s dominant supplier of microprocessors. An astute student of business, Grove recognized the latent power in the MBO system and inserted it as a key piece of his management philosophy at Intel. However, he made a number of modifications to the model, transforming it into the framework most of us would recognize today. In Grove’s thinking, a successful MBO system need answer just two fundamental questions: (1) Where do I want to go (the objective) and (2) How will I pace myself to see if I am getting there? That second question, simple as it may seem, turned out to be revolutionary in launching the OKRs movement by attaching what would come to be known as a “key result” to an objective.

A guiding principle in Grove’s use of objectives and key results was driving focus. As he put it:

Here, as elsewhere, we fall victim to our inability to say “no”—in this case, to too many objectives. We must realize—and act on the realization—that if we try to focus on everything, we focus on nothing. A few extremely well-chosen objectives impart a clear message about what we say “yes” to and what we say “no” to—which is what we must have if an MBO system is to work.

He didn’t stop at limiting the number of objectives, however. Grove modified the Drucker model in a number of important ways.

First, he suggested setting objectives and key results more frequently, recommending quarterly or in some cases monthly. This was in recognition of the fast pace of the industry in which he found himself, but also reflected the fundamental importance of adopting fast feedback into an organization’s culture. Grove also insisted that objectives and key results not be considered a “legal document” binding employees to what they proposed and basing their performance review solely on their results. He believed OKRs should be just one input used to determine an employee’s effectiveness.

Another important ingredient of success at Intel was ensuring OKR creation was a mix of top-down and bottom-up involvement. As noted earlier, Drucker assumed this mechanism in his rendering of the model, but many organizations, fixed in a purely hierarchical mindset, abandoned it. Not so with Grove. He intuited the critical nature of employee involvement in fostering self-control and motivation.

Finally, Grove understood the importance of introducing the concept of stretch into OKRs. In his words:

When the need to stretch is not spontaneous, management needs to create an environment to foster it. In an MBO system, for example, objectives should be set at a point high enough so that even if the individual (or organization) pushes himself hard, he will still only have a 50-50 chance of making them. Output will tend to be greater when everybody strives for a level of achievement beyond his immediate grasp, even though trying means failure half the time. Such goal-setting is extremely important if what you want is peak performance from yourself and your subordinates.

At this point in our story, we’re just one degree of separation from Google and the OKRs boom we’re witnessing today. John Doerr represents that link in the chain. Now a partner at the venerable Silicon Valley venture capital firm Kleiner Perkins Caulfield and Byers, Doerr started his career at Intel and enthusiastically soaked up the many management lessons Andy Grove was only too pleased to volunteer. Among them, of course, was objectives and key results. Doerr recognized the value and potential of the model and continues to share it with entrepreneurs to this day.

Two of his early students were Larry Page and Sergey Brin, who you may know as the founders of Google. Here’s how John Doerr recalls the introduction of OKRs at Google:

Shortly after we invested, we had our board meetings around a ping pong table above the ice cream parlor on University Avenue, and Larry called an all-hands meeting because I’d shown him this OKR thing . . . I went through a slide presentation that I still have today . . . and Larry and Sergey—so smart, so aggressive, so ambitious, so interested in not just making but achieving moonshots, embraced the system and that was thirty or so people and to this day I think they’re part of the culture, they’re part of the DNA, at Google they’re part of the language the actual words that you use. Larry embraced it for himself, for the company and he uses it as a tool to actually empower people. People think it’s about accountability and it does achieve that as a byproduct. It’s really a way to build a social contract in your organization that says I’m going to sign up to do this amazing stuff.

One of our favorite “Drucker-isms” is this: “The most serious mistakes are not being made as a result of wrong answers. The truly dangerous thing is asking the wrong questions.”

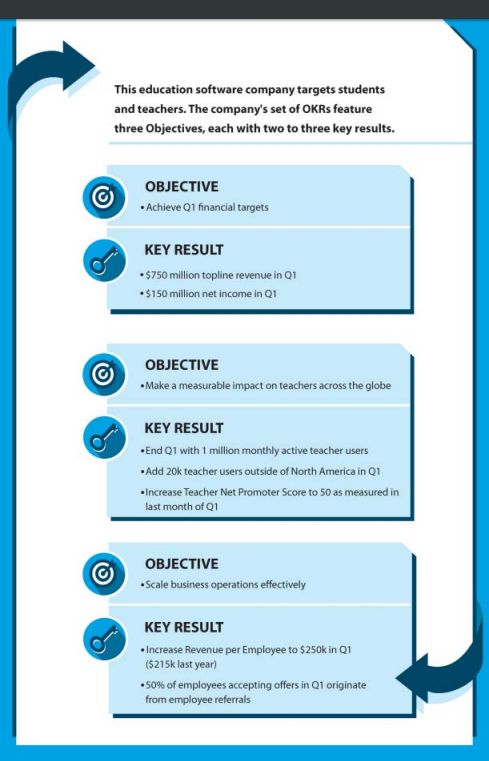

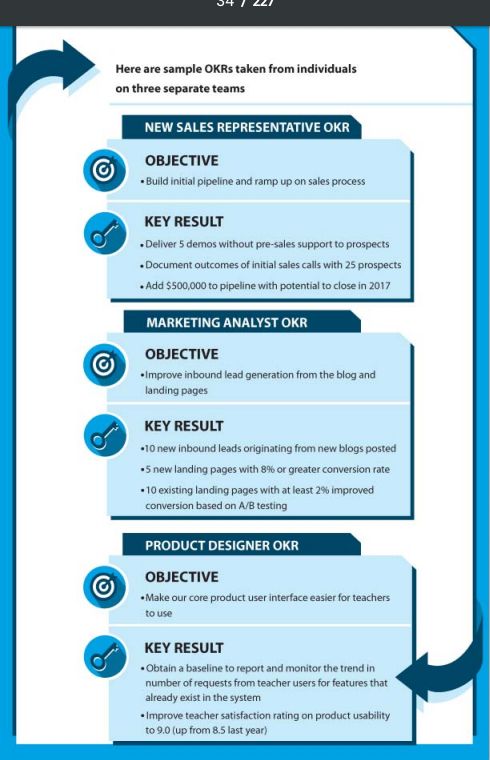

OBJECTIVES

An objective is a concise statement outlining a broad qualitative goal designed to propel the organization forward in a desired direction. Basically, it asks, “What do we want to do?” A well-worded objective is time-bound (doable in a quarter) and should inspire and capture the shared imagination of your team.

As an example, we’re creating a series of collateral materials for this book, and one of our objectives this quarter is: “Design a compelling website that attracts people to OKRs.” The objective is concise (just nine words), qualitative (no numbers here—that’s the province of the key result), time-bound (we’re confident we can create a design this quarter), and inspirational (it’s exciting to engage our creativity in producing a site that people will find both helpful and aesthetically appealing).

KEY RESULTS

A key result is a quantitative statement that measures the achievement of a given objective. If the objective asks, “What do we want to do?” the key result asks, “How will we know if we’ve met our objective?” In our previous definition, some may quibble with the use of the word quantitative, arguing that if a key result measures achievement, then by its very nature it’s quantitative. Point taken, but we want to err on the side of too much information here to ensure that you recognize the vital importance of stating your key results as numbers.

The challenge, and ultimately value, of key results is in forcing you to quantify what may appear to be vague or nebulous words in your objective. Using our example objective of “Design a compelling website that attracts people to OKRs,” we’re now committed to designating what we mean by “compelling” and “attracts.” As you’ll discover with your own key results, there are no given translations of words like compelling and attracts into numbers; you must determine what the words mean specifically to you in your unique business context. Here are our key results (most objectives will have between two and five key results—more on that later in the book).

- 20 percent of visitors return to the site in one week.

- 10 percent of visitors inquire about our training and consulting services.

In the process of writing this book, we conducted an extensive amount of research, which translates primarily into an abundance of reading—books, white papers, articles, blog posts, and so on. They all differ based on their unique subject matter, but the one common denominator amongst virtually all of them can be found within the opening sentence or two. Invariably, the case is made that we live in the most volatile of times. The very foundations of our corporate thinking are challenged, forcing us to swiftly extend the frontiers of knowledge to stay one short step ahead of the change monster bearing down upon us. With this book, we wanted to do something a little different by allowing you to breathe a little deeper as we begin our journey together, because in some ways economic life, at least in the developed world, is actually less turbulent than it’s ever been. In the United States, for example, the volatility of gross domestic product (GDP) growth decreased from 3 percent in the period of 1946 to 1968 to just 1.2 percent from 1985 to 2006. Both inflation and corporate profit growth also saw similar reductions in volatility during the period.11 Today’s technological wonders can make our heads spin, but they’re really no more destabilizing than the advent of railroads, telephones, automobiles, mass production, or radio were in their day

Rather than disruption, we could term the changes Uber and others are employing as “business model innovations,” but regardless of the terminology employed the fact remains, there are hungry (nay, starving) companies that you’ve never heard of, who are at this very moment plotting to steal your market share. No industry is immune to this assault. Take shipping companies. They face a very unanticipated threat: 3D printing. As more manufacturers have the option to print parts and products in finished form onsite, shipments by air, sea, and roadway will plummet. It is estimated that as much as 41 percent of the air cargo business, 37 percent of ocean container shipments, and 25 percent of truck deliveries are vulnerable to 3D printing. Given the undeniable threat, it’s vital that organizations embrace agility and possess the ability to swiftly modify their business model based on new information. Once again, we believe OKRs will prove beneficial in this task.

The business press is replete with stories relating the “war for talent” among corporations striving to stock their ranks with the best, brightest, and most highly engaged employees. It’s a simple fact that no organization can succeed without skilled and motivated teams working in alignment with overall objectives. Of all the adjectives appearing in the last two sentences the one that has the greatest hold on executive attention is engagement. To put it bluntly, we’re currently facing an engagement crisis.

Before we present the litany of statistics to bolster this point, let’s define the term, because there is much confusion about what engagement is and is not. First, what it’s not. Engagement does not represent employee happiness and it’s much bigger than employee satisfaction. Kevin Kruse, author of Engagement 2.0, defines engagement as the emotional commitment an employee has to the organization and its goals. This emotional commitment means engaged employees actually care about their work and the company. They don’t work just for a salary, or for a promotion to the next rung on the ladder, but work passionately on behalf of the organization’s goals. When employees care—when they are truly engaged—they use discretionary effort.

Here’s a simple, but telling, example we observed at a client organization. We were scheduled to meet with the CEO of a small fast-food chain in Southern California. The meeting location was one of its restaurants, and we arrived quite early. None of the employees knew who we were, so there was certainly no incentive for them to try and impress us in any way. At one point, we noticed an employee rushing across the floor towards the door. Our first thought was that someone had attempted to leave without paying, but in fact we were wrong. As he approached the door the employee bent over and picked up a discarded napkin. He placed it in the trash and went back behind the counter to assist the next customer. You could say he was simply doing his job, but again, no one was watching. He could have easily left the trash on the floor, but he took the discretionary step of leaving his station to keep the restaurant clean.

Unfortunately, the engagement numbers in the United States and around the world are dismally low—Gallup reports only 13 percent of the global workforce is highly engaged. In the United States, the number is about 30 percent. And this produces a real penalty—by some estimates, low engagement costs $17,000 per employee per year in lost productivity, absenteeism, and so on. Seventeen thousand doesn’t sound that big, so let’s amplify it by extrapolating that to the entire U.S. workforce. We’re then looking at approximately $450 billion to $550 billion in lost productivity each year. But we believe there may be an even bigger cost—the inability to contribute effectively to strategy execution. Disengaged employees are not willing to expend the discretionary effort necessary to sense new opportunities, take calculated risks, or propose business model innovations that may keep their firms ahead of rivals.

The good news is that organizations recognize what is at stake in this battle, and have significantly expanded efforts to enhance engagement. Annual employee satisfaction and engagement surveys are being phased out, replaced by employee listening tools such as pulse surveys, anonymous social tools, and perhaps most importantly regular check-ins with, and feedback from, managers.

We’ve laid out some considerable challenges on the previous pages. Fortunately, as we’ve alluded to, OKRs can assist in overcoming these hurdles, and launch you on a trajectory of sustained success. Let’s look at some of the many benefits of the OKRs approach.

单词列表:

| words | sentence |

|---|---|

| nascent | As we write this, the OKRs field is still relatively nascent in terms of standard practices and proven procedures |

| pitfalls | falling prey to potential pitfalls that can derail this or any change effort |

| derail | falling prey to potential pitfalls that can derail this or any change effort |

| crystal clear | but when you’re at work you need to be crystal clear about the destination |

| nimble | in a fast-changing industry with nimble competitors emerging rapidly |

| metrics | but by focusing on a core set of metrics to learn about what was |

| fivefold | nearly fivefold to a large majority of employees |

| legions | The framework has been embraced by legions of organizations around the globe |

| taxonomy | The Scorecard’s taxonomy has swollen over the years since its founding in the early 1990s |

| swollen | The Scorecard’s taxonomy has swollen over the years since its founding in the early 1990s |

| yearning | one comprised of teams yearning for simple, yet powerful methods to |

| accountability | OKRs must be created throughout the organization in order to drive engagement, accountability, and focus |

| cadence | But, rather than adopt a more frequent cadence |

| acumen | those with keen business acumen saw the underlying power of Drucker’s words |

| soaked up | Doerr started his career at Intel and enthusiastically soaked up the many management lessons |

| all-hands meeting | and Larry called an all-hands meeting because I’d shown him this OKR thing |

| parlor | From those modest beginnings at a board meeting above an ice cream parlor |

| behemoth | As an example of the behemoth’s place in the business zeitgeist, if you were to |

| zeitgeist | As an example of the behemoth’s place in the business zeitgeist, if you were to |

| paper towels | If someone were to write a book sharing how often Google changes the paper towels in their restrooms |

| ascendance | began their ascendance immediately upon Google’s adoption of the program |

| inexorable | the movement really began to gain inexorable momentum |

| imperative | it’s imperative that you use consistent definitions for OKRs terms and concepts |

| pundits | Strategy pundits are fond of noting that strategy is as much about what not to do |

| exclusively | key results are typically (and almost exclusively) quantitative in nature |

| concise | An objective is a concise statement outlining a broad qualitative goal |

| quibble | some may quibble with the use of the word quantitative |

| quantitative | some may quibble with the use of the word quantitative |

| temptation | and thus there is a temptation to eschew further study |

| eschew | and thus there is a temptation to eschew further study |

| peril | However, you do so at your significant peril |

| garner | should you hope to garner the benefits promised by the system |

| gross domestic product | for example, the volatility of gross domestic product (GDP) growth decreased from 3 percent in the period of 1946 to 1968 to just 1.2 percent from 1985 to 2006 |

| exhale | So we can all exhale just a bit: |

| most peg | but most peg the rate of successful execution at a best case of 25 to 35 percent |

| stunningly | while less optimistic pundits propose a stunningly low 10 percent |

| mantra | “Grow or Die” is a much-repeated mantra throughout corporate conference rooms here in the United States |

| sanguine | because most executives are extremely sanguine when it comes to the growth prospects facing their firms |

| sobering | Here’s a sobering statistic that just may dampen your enthusiasm |

| dampen | Here’s a sobering statistic that just may dampen your enthusiasm |

| bluntly | To put it bluntly, we’re currently facing an engagement crisis |