【Linux】线程概念

目录

1. 线程

1.1. 线程概念

1.2. Linux下的线程

线程的优点

线程的缺点

1.3. 进程与线程

2.线程控制

2.1. 线程创建

2.2. 线程等待

2.3. 线程终止

2.4. 线程分离

3.线程ID

1. 线程

1.1. 线程概念

一般而言,线程是在进程内部运行的一个执行分支(执行流),属于进程的一部分,粒度要比进程更加细和轻量化。

一个进程内是可能存在多个进程的。

那么操作系统内就存在更多的线程,所以操作系统管理线程的方式依旧是:先描述,再组织。

既然进程有PCB,那么线程也可以有TCB,其内部数据也类似于PCB。

但是上面操作只是常规OS的做法,比如Windows。

1.2. Linux下的线程

但是在Linux上不是这样做的。

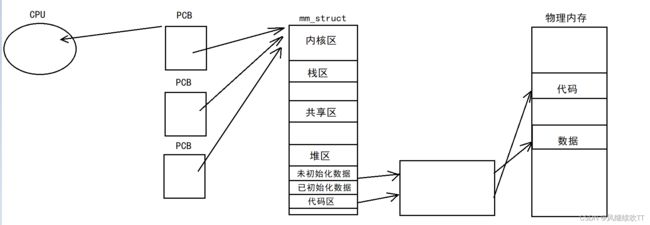

在Linux操作系统中,不存在真正意义上的线程,不会为线程创建TCB,而是创建PCB(task_struct) 模拟线程。(好处是不用维护复杂的进程和线程的关系,不用单独为线程设计任何算法,直接使用进程的相关方法)

一个进程内的PCB共享一个地址空间,当前进程的资源(代码+数据),被划分成若干份,让每个PCB使用。

CPU此时看到的PCB是小于等于之前进程的PCB的概念,一个PCB就是一个需要被调度的执行流。

所以今天的进程就可以被重新定义:

进程是承担分配系统资源的基本实体。

线程是CPU调度的基本单位,承担进程部分资源的基本实体(进程划分资源给线程)。

CPU在调度PCB时不会专门去区分到底是线程还是进程。

线程的优点

这样组织线程的方式,是Linux操作系统优于其他操作系统的原因之一。

Linux进程相比于其他操作系统上的进程更加轻量化,其原因在于 OS创建线程 和 CPU调度线程;所以Linux进程又被称为轻量级进程。

创建一个新线程的代价要比创建一个新进程小得多

与进程之间的切换相比,线程之间的切换需要操作系统做的工作要少很多

线程占用的资源要比进程少很多

能充分利用多处理器的可并行数量

在等待慢速I/O操作结束的同时,程序可执行其他的计算任务

计算密集型应用,为了能在多处理器系统上运行,将计算分解到多个线程中实现

I/O密集型应用,为了提高性能,将I/O等待就绪操作重叠。线程可以同时等待不同的I/O操作

线程不是越多越好,线程太多会导致线程间被过度切换,影响效率。

线程的缺点

Linux线程因为是用进程模拟的,所以Linux下不会给用户提供直接操作线程的接口,而是提供在同一个地址空间内创建PCB的方法,分配资源给指定的PCB的接口。所以对用户不太友好,这是这样设计的缺点。(这里的用户指的是:系统级工程师)

性能损失 一个很少被外部事件阻塞的计算密集型线程往往无法与共它线程共享同一个处理器。如果计算密集型 线程的数量比可用的处理器多,那么可能会有较大的性能损失,这里的性能损失指的是增加了额外的 同步和调度开销,而可用的资源不变。

健壮性降低 编写多线程需要更全面更深入的考虑,在一个多线程程序里,因时间分配上的细微偏差或者因共享了 不该共享的变量而造成不良影响的可能性是很大的,换句话说线程之间是缺乏保护的。

缺乏访问控制 进程是访问控制的基本粒度,在一个线程中调用某些OS函数会对整个进程造成影响。

编程难度提高 编写与调试一个多线程程序比单线程程序困难得多

如果进程中的一个线程运行时出问题了(崩溃),整个进程都会崩溃。

1.3. 进程与线程

所有的轻量级进程(可能是线程)都是在进程的内部运行 (地址空间:标识进程所能看到的大部分资源!)

进程是资源分配的基本单位,线程是调度的基本单位。

进程具有独立性,可以有部分共享资源(比如:管道,IPC资源)

线程大部分资源是共享的(例如:代码、进程数据、文件描述符、信号处理方式),可以有部分资源是私有的(例如:PCB、栈、上下文)

ps:每个线程是有自己的独立栈,保存线程运行时形成的临时数据;上下文中保存的是CPU调度时存放在寄存器中的临时数据。

2.线程控制

为了方便对线程进行操作,Linux提供了原生线程库,在使用时需要手动链接。

2.1. 线程创建

使用接口:

pthread_created: 创建线程

#includeint pthread_create(pthread_t *thread, const pthread_attr_t *attr, void *(*start_routine) (void *), void *arg); // Compile and link with -pthread. 使用需链接原生线程库 // pthread_t:实际为无符号整型,这里thread代表线程id // attr:线程属性,一般不需要自己设置,默认为NULL // start_routine:函数指针,为该线程需执行的对应任务 // arg:传入start_routine回调函数内的参数 // 创建成功返回0,失败返回-1,并对全局变量errno赋值,指示错误信息 pthread_self:获取自己的线程id

#includepthread_t pthread_self(void); // Compile and link with -pthread.

演示代码:

#include

#include

#include

void *thread_run(void *arg)

{

while(1)

{

printf("我是新线程[%s], 我的线程ID是:%lu\n", (const char*)arg,pthread_self());

sleep(1);

}

}

int main()

{

pthread_t tid;

pthread_create(&tid, NULL, thread_run, (void*)"new thread");

while(1)

{

printf("我是主线程,我创建的线程ID是:%lu\n",tid);

sleep(1);

}

return 0;

} Makefile:

mythread:mythread.c

gcc -o $@ $^ -lpthread #链接原生线程库

.PHONY:clean

clean:

rm -f mythread

运行结果:

ps -aL:查看线程:

这里两张图片中的线程ID不同,原因后面讲。

一次创建多个线程:

pthread_t tid[5];

int i = 0;

for(i = 0; i < 5; ++i)

{

pthread_create(tid+i, NULL, thread_run, (void*)"new thread");

}2.2. 线程等待

一般而言,线程也是需要被等待的,如果不等待,可能会导致类似"僵尸进程"的问题。

调用接口:

pthread_join:等待线程

#includeint pthread_join(pthread_t thread, void **retval); // Compile and link with -pthread. // 等待成功返回0,失败返回错误码 // thread:需要等待的线程 // retval:输出型参数,获取线程函数的返回值(由于该函数的返回值是一级指针,所以必须要传二级指针才能带回)

演示代码:

#include

#include

#include

void *thread_run(void *arg)

{

printf("我是新线程[%s], 我的线程ID是:%lu\n", (const char*)arg,pthread_self());

sleep(1);

return (void*)666;

}

#define NUM 1

int main()

{

pthread_t tid[NUM];

int i = 0;

for(i = 0; i < NUM; ++i)

{

pthread_create(tid+i, NULL, thread_run, (void*)"new thread");

}

void *status = NULL;

pthread_join(tid[0], &status);

printf("ret: %d\n",(int)status);

return 0;

} 值得注意的是,如果线程异常退出,对错误的处理不是由线程完成,而是进程去完成的。线程中没有信号。

由于这里是用指针接收,如果要返回的数据大于4个或8个字节,需要封装成结构体或者类返回。

2.3. 线程终止

线程终止有三种方法:

函数中return(main函数return表示主线程或者进程退出,其他线程函数return只代表当前线程退出)

新线程通过调用pthread_exit终止(exit是终止进程,如果在线程中调用会终止整个进程)

主线 程调用pthread_cancel,取消目标线程。

pthread_exit:终止当前线程

#includevoid pthread_exit(void *retval); // Compile and link with -pthread. // retval:返回值 pthread_cancel:主线程取消其他线程

#includeint pthread_cancel(pthread_t thread); // Compile and link with -pthread. // thread:目标线程

演示代码:

#include

#include

#include

void *thread_run(void *arg)

{

printf("我是新线程[%s], 我的线程ID是:%lu\n", (const char*)arg,pthread_self());

sleep(1);

pthread_exit((void*)666); // 终止线程,返回值为666

}

void *thread_run2(void*arg)

{

while(1)

{

printf("我是新线程[%s], 我的线程ID是:%lu\n", (const char*)arg,pthread_self());

sleep(1);

}

}

#define NUM 2

int main()

{

pthread_t tid[NUM];

pthread_create(tid+0, NULL, thread_run1, (void*)"new thread");

pthread_create(tid+1, NULL, thread_run2, (void*)"new thread");

pthread_cancel(tid[1]); // 取消第二个线程

void *status = NULL;

pthread_join(tid[0], &status);

printf("ret: %d\n",(int)status);

void *status1 = NULL;

pthread_join(tid[1], &status1);

printf("ret: %d\n",(int)status1);

return 0;

} 如果线程是正常被取消的,他的退出码是-1,反之如果一个线程的退出码是-1,就证明他是被取消的。

如果新线程用pthread_cancel取消主线程,进程还不会退出,会导致进程出现僵尸状态。

一般使用前两中线程终止的方式。

2.4. 线程分离

分离之后的线程不需要被join,运行完毕之后会自动释放PCB,其作用类似与进程信号中的SIGCHLD。

调用接口:

pthread_detach: 分离线程

#includeint pthread_detach(pthread_t thread); // Compile and link with -pthread. // thread:需分离的线程id,可以新线程分离自己,也可以主线程分离新线程

演示代码:

#include

#include

#include

void *thread_run(void *arg)

{

pthread_detach(pthread_self()); // 线程分离

printf("我是新线程[%s], 我的线程ID是:%lu\n", (const char*)arg,pthread_self());

sleep(1);

return (void*)666;

}

#define NUM 1

int main()

{

pthread_t tid[NUM];

int i = 0;

for(i = 0; i < NUM; ++i)

{

pthread_create(tid+i, NULL, thread_run, (void*)"new thread");

}

sleep(2); // 给新线程时间让他分离

void *status = NULL;

int ret = pthread_join(tid[0], &status);

printf("status: %d ret: %d\n",(int)status, ret);

return 0;

} ![]()

pthread_join返回值不是0,说明等待失败了。

3.线程ID

回到上面的问题为什么ps -aL中查看到的线程id与程序运行中输出的id值不一样?

首先LWP是操作系统内核中的,而右边的线程id是线程库中的,并没有规定两个值必须相同。而为什么两个值不一样,其实我们回答不了。

#include

#include

#include

void*run(void* arg)

{

const char* str = (const char*)arg;

while(1)

{

printf("%s id: 0x%x\n", arg, pthread_self());

sleep(1);

}

}

int main()

{

pthread_t tid;

pthread_create(&tid, NULL, run, (void*)"new pthread");

while(1)

{

printf("main pthead id: 0x%x\n", pthread_self());

sleep(1);

}

return 0;

} 我们查看到的线程id是pthread库的线程id,不是Linux内核中的LWP,pthread库的线程id是一个内存地址!

其组织方式如下图所示:

而操作系统内核中的LWP与线程id数量其实是1:1的关系,当新线程被创建,操作系统就会为它创建一个LWP。

而操作系统内核中的LWP与线程id数量其实是1:1的关系,当新线程被创建,操作系统就会为它创建一个LWP。

为了操作系统能够调度线程,LWP被保存在struct pthread结构体中。