[Linux]----文件操作(重定向+缓冲区)

文章目录

- 前言

- 一、重定向

-

- 具体操作

-

- dup2

- 二、关于缓冲区的理解

-

- 1. 什么是缓冲区

- 2. 为什么要有缓冲区

- 3. 缓冲区在哪里

-

- 刷新策略机制

- 如果在刷新之前,关闭了fd会有什么问题?

- FLIE内部的封装

- 特殊情况

- 模拟实现封装C标准库

- 标准输出和标准错误

- 总结

前言

本节继续基于上节文件描述符继续往下拓展,讲一讲关于文件操作的重定向和缓冲区。

正文开始!

首先来基于上节课的问题

#include然后我们将fflush()这一行代码取消注释后

![[Linux]----文件操作(重定向+缓冲区)_第1张图片](http://img.e-com-net.com/image/info8/be0b56d0fc644ecbacdfe258f9e33e48.png)

我们可以发现打印内容到了文件中了。至于为什么要用fflush()函数,需要了解到缓冲区的内容,接下来带大家理解!

那我有一个问题了?为什么不往显示器去打印,而是打印在了文件中呢???

一、重定向

![[Linux]----文件操作(重定向+缓冲区)_第2张图片](http://img.e-com-net.com/image/info8/9734ae12047f4e949930807308660d86.jpg)

如果我们要进行重定向,上层只认0,1,2,3这样的fd,我们可以在OS内部,通过一定的方式调整数组的特定下标内容够(指向),我们就可以完成重定向操作!

对于上图,我们进行重定向后,fprintf并不知道1号文件描述符指向了"log.txt"文件,而继续向1号文件描述符打印东西。

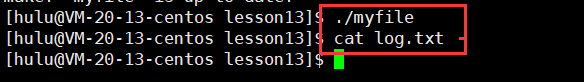

具体操作

上面的一堆的数据,都是内核数据结构。只有谁有权限呢???

必定是操作系统(OS)---->必定提供系统结构!

dup2

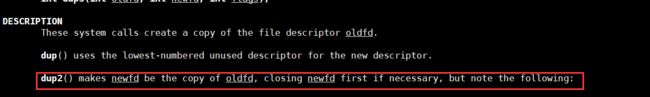

相比于dup,dup2更复杂一些,我们今天主要使用多duo2进行重定向操作!

stdout–>1 log.txt–>fd

-

那么对于dup2()接口,谁是谁的一份拷贝呢?

对于上面框起来的内容翻译就是newfd是oldfd的一份拷贝,就是把oldfd的内容放置newfd里面。最后只剩oldfd了!!!

-

参数怎么传呢??

我们要输出重定向到文件中,即就是stdout的输出到文件中,即就是1号文件描述符的内容要指向新创建文件的描述符。

dup2(fd,1);

int main()

{

int fd=open("log.txt",O_WRONLY|O_CREAT|O_TRUNC,0666);

if(fd<0)

{

perror("open");

return 1;

}

dup2(fd,1);

fprintf(stdout,"打开文件成功,fd=%d",fd);

fflush(stdout);

close(fd);

}

输入重定向

int main()

{

int fd=open("log.txt",O_RDONLY);

if(fd<0)

{

perror("open");

return 1;

}

dup2(fd,0);

char line[64];

while(fgets(line,sizeof(line),stdin)!=NULL)

{

printf(line);

}

fflush(stdout);

close(fd);

}

二、关于缓冲区的理解

1. 什么是缓冲区

- 缓冲区的本质:就是一段内存。

2. 为什么要有缓冲区

- 解放使用缓冲区的进程时间

- 缓冲区的存在可以集中处理数据刷新,减少IO的次数,从而达到提高整机的效率的目的!

3. 缓冲区在哪里

我来写一份代码带大家验证一下!

int main()

{

printf("hello printf\n"); //stdout-->1

const char* msg="hello write\n";

write(1,msg,strlen(msg));

}

int main()

{

printf("hello printf"); //stdout-->1

const char* msg="hello write";

write(1,msg,strlen(msg));

}

write可是立即刷新的!

所以我们根据以上的实验现象我们可以发现stdout必定封装了write!

那么这个缓冲区不在哪里?? ---->一定不在wirte内部!

所以我们曾经讨论的缓冲区,不是内核级别的!

所以这个缓冲区在哪里???—>只能是C语言提供的!!!(语言级别的缓冲区)

因为printf是往stdout中打印,stdout—>FILE—>struct—>封装很多的属性---->fd—>该FILE对于的语言级别的缓冲区!

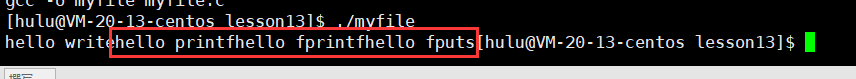

刷新策略机制

int main()

{

printf("hello printf");//stdout->1->封装了write

fprintf(stdout,"hello fprintf");

fputs("hello fputs",stdout);

const char* msg="hello write";

write(1,msg,strlen(msg));

return 0;

}

什么时候刷新?

- 无缓冲(立即刷新)

- 行缓冲(逐行刷新)—>显示器文件

- 全缓冲(缓冲区满,刷新)—>块设备对应的文件(磁盘文件)

无缓冲的特殊情况

a.进程退出

b.用户强制刷新

如果在刷新之前,关闭了fd会有什么问题?

int main()

{

printf("hello printf");//stdout->1->封装了write

fprintf(stdout,"hello fprintf");

fputs("hello fputs",stdout);

const char* msg="hello write";

write(1,msg,strlen(msg));

close(1);

//close(stdout->_fileno);//和上面close(1)效果相同

return 0;

}

![[Linux]----文件操作(重定向+缓冲区)_第9张图片](http://img.e-com-net.com/image/info8/4221d6def2e54d82a83f78f1d923f2cf.png)

一开始我们只是把数据写入到FILE结构体的缓冲区,然后你把文件描述符给关了,当然就写不进文件中了!!!

既然缓冲区在FILE内部,在C语言中,而我们每一次打开一个文件,都要有一个FILE*会返回!!

那就意味着,每一个文件都有一个fd和属于他自己的语言级别的缓冲区!!!

FLIE内部的封装

在/usr/include/libio.h

struct _IO_FILE {

int _flags; /* High-order word is _IO_MAGIC; rest is flags. */

#define _IO_file_flags _flags

//缓冲区相关

/* The following pointers correspond to the C++ streambuf protocol. */

/* Note: Tk uses the _IO_read_ptr and _IO_read_end fields directly. */

char* _IO_read_ptr; /* Current read pointer */

char* _IO_read_end; /* End of get area. */

char* _IO_read_base; /* Start of putback+get area. */

char* _IO_write_base; /* Start of put area. */

特殊情况

int main()

{

const char* str1="hello printf\n";

const char* str2="hello fprintf\n";

const char* str3="hello fputs\n";

const char* str4="hello write\n";

//C库函数

printf(str1);

fprintf(stdout,str2);

fputs(str3,stdout);

//系统接口

write(1,str4,strlen(str4));

//是调用完了上面的代码,才执行的fork

fork();

}

对代码去掉’\n’

int main()

{

const char* str1="hello printf";

const char* str2="hello fprintf";

const char* str3="hello fputs";

const char* str4="hello write";

//C库函数

printf(str1);

fprintf(stdout,str2);

fputs(str3,stdout);

//系统接口

write(1,str4,strlen(str4));

//是调用完了上面的代码,才执行的fork

fork();

}

- 刷新的本质,就是把缓冲区的数据写到OS内部,清空缓冲区!

- 缓冲区是自己的FILE内部维护的,属于父进程

- 子进程也继承了父进程的缓冲区,也就打印了父进程缓冲区的内容!

模拟实现封装C标准库

只封装了C语言库的一部分!

#include标准输出和标准错误

#include我们发现打1的都不见了

![[Linux]----文件操作(重定向+缓冲区)_第16张图片](http://img.e-com-net.com/image/info8/7b9c361c4c4d4a5b98f20e31918e836f.png)

![[Linux]----文件操作(重定向+缓冲区)_第17张图片](http://img.e-com-net.com/image/info8/05cbe28fc713447d9492013cf9a8dac7.jpg)

向stdout里面打的都重定向到log.txt文件中,stderr继续打印到显示器。

./a.out >stdout.txt 2>stderr.txt

一条语句进行两次重定向

那么意义在哪里呢?

可以区分那些是程序日常输出,那些是错误!

我们也可以将上面的两个文件打印在一个文件

./a.out >all.txt 2>&1

总结

(本章完!)

下节课我们基于重定义的学习来完善我们之前写的myshell!!!

![[Linux]----文件操作(重定向+缓冲区)_第3张图片](http://img.e-com-net.com/image/info8/3bc4cb72448a40808f9593e1c3a4b0e3.png)

![[Linux]----文件操作(重定向+缓冲区)_第4张图片](http://img.e-com-net.com/image/info8/8a751dda799b439eb2bdcdf3e923568f.png)

![[Linux]----文件操作(重定向+缓冲区)_第5张图片](http://img.e-com-net.com/image/info8/58c3d6797663406c907e5e05cb2e04a2.png)

![[Linux]----文件操作(重定向+缓冲区)_第6张图片](http://img.e-com-net.com/image/info8/99eb954bea154732879a813ab623e663.png)

![[Linux]----文件操作(重定向+缓冲区)_第7张图片](http://img.e-com-net.com/image/info8/70495551f7e744ebb78b2cb160a79060.png)

![[Linux]----文件操作(重定向+缓冲区)_第8张图片](http://img.e-com-net.com/image/info8/d14d392bfd5d43cfadb7bf6dde8443f2.jpg)

![[Linux]----文件操作(重定向+缓冲区)_第10张图片](http://img.e-com-net.com/image/info8/af655c90cc4845cc8eb6db347ea242cd.jpg)

![[Linux]----文件操作(重定向+缓冲区)_第11张图片](http://img.e-com-net.com/image/info8/b8e7af1096f346479397abff25d4531a.jpg)

![[Linux]----文件操作(重定向+缓冲区)_第12张图片](http://img.e-com-net.com/image/info8/986f27c02dc94e19a22d1cada42687f9.png)

![[Linux]----文件操作(重定向+缓冲区)_第13张图片](http://img.e-com-net.com/image/info8/e4b15ff32cf1439bb468d2316909956c.jpg)

![[Linux]----文件操作(重定向+缓冲区)_第14张图片](http://img.e-com-net.com/image/info8/8432ad0bf3eb40fe9853caff3528b6af.png)

![[Linux]----文件操作(重定向+缓冲区)_第15张图片](http://img.e-com-net.com/image/info8/730afa265b5547b7968da578cfa3bd6f.png)

![[Linux]----文件操作(重定向+缓冲区)_第18张图片](http://img.e-com-net.com/image/info8/71279e6b981b4a77adfa42327aa9ced6.png)

![[Linux]----文件操作(重定向+缓冲区)_第19张图片](http://img.e-com-net.com/image/info8/ff21e9d7ceac4659a8d7cbd48f8496ee.png)