一篇非常适合新手学习Biztalk的文章

An XML Guru's Guide to BizTalk Server 2004, Part I

Aaron Skonnard

Contents

Contents

Who would have believed that XML, such a seemingly trivial technology, could revolutionize an industry? It may have seemed like a long shot in the beginning, but the XML aficionados saw something special and pragmatic right away—a sort of duct tape for the world's information systems. But not all developers felt this way. Some were disappointed by the lack of tool support that would bring XML to life.

Given its place today, however, I don't think anyone could say that XML was all hype. It has revolutionized the way we think about distributed computing, given birth to Web services and service orientation, and continually spawns newer, better tools. One such tool, BizTalk

® Server 2004, is poised to finally bring some of XML's benefits to the masses by providing some long-awaited magic.

BizTalk State of Affairs

BizTalk Server 2000 laid the foundation for simplifying common XML use cases in the enterprise. But, needless to say, the final package had some warts. It was hard to install, configure, and operate. Its available tools confused developers and, as a result, was never able to gain significant traction.

Since that humble beginning, the product has evolved significantly. BizTalk Server 2002 came shortly after the initial release, and provided some minor improvements. The big change, however, came with BizTalk Server 2004 when the entire product was rewritten for the Microsoft

® .NET Framework. BizTalk Server 2004 came with some major simplifications and a new toolset integrated with Visual Studio

® .NET—just the right ingredients for a good developer experience.

And future versions look even better. Microsoft recently released a preview of the upcoming BizTalk Server 2006 (code-named "Pathfinder"), which continues to build on the foundation of .NET, while introducing additional improvements and simplifications. One of the primary goals of the 2006 release is to simplify the user experience, especially the installation, configuration, and operation processes, which have caused so much pain in the past. I've heard some say one of their primary goals was to achieve a SQL Server

™-like Next?Next?Next installation. The current release looks very promising.

Theory vs. Reality

One of the first things I noticed after playing with BizTalk Server 2004 is how grounded the product is in reality. Most businesses don't have the luxury of being able to throw away existing investments, so integrating legacy systems with a wide range of communication protocols and data formats is a very big challenge.

While advocates of Web services believe that their approach is the solution to these enterprise challenges, that approach alone would require updating all legacy systems (at least those that don't speak Web services today). If Web services were the answer, everything would have to speak SOAP and the Web services family of specifications. That's a tall order for most enterprises. In addition, most Web services stacks only support a few protocols and are not message-oriented by design, which can limit you when dealing with certain integration scenarios.

The BizTalk folks took a different approach to this problem. Instead of enforcing common protocols, BizTalk Server supports a myriad of protocols through its adapter framework. BizTalk Server provides numerous adapters in the box that address some of the most mainstream use cases, but what's really exciting is the suite of nearly 100 partner adapters you can plug into. You should be able to find one for just about any common enterprise application or technology in use today. Of course, in addition to all of this flexibility, BizTalk Server doesn't require the use of SOAP or WS-*, or even XML. Through BizTalk pipelines and maps, you can support a variety of different data formats to fit your needs, including common flat files and Electronic Data Interchange (EDI).

BizTalk also embraces core XML technologies, such as XPath and XSLT, to deal with tough problems like versioning or alternate data formats to fit a particular customer's needs. In addition, BizTalk provides sophisticated integration with today's evolving Web services technologies when dealing with newer SOAP-savvy applications. Overall, BizTalk Server 2004 offers a message-oriented approach grounded in today's realities.

BizTalk Server Architecture

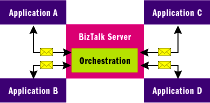

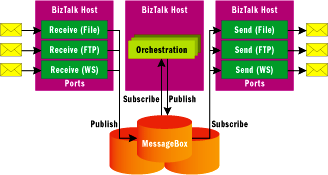

The BizTalk Server 2004 architecture is neatly organized into two primary buckets: messaging and orchestration. The messaging layer is focused on the details of sending and receiving messages or in other words, "connecting the dots" between applications. In order for an application to participate with BizTalk Server, it needs to be able to communicate via messages. The orchestration layer is focused on coordinating numerous individual message exchanges (see

Figure 1), dealing with sequencing and flow, error handling and transactions, and so on. Most BizTalk Server 2004 features and technologies fit nicely into one of these buckets.

Figure 1

Messaging vs. Orchestration

The messaging architecture provides the foundation for the entire product. You can tap directly into the messaging layer (more on this shortly), or you can interface with it indirectly using the orchestration layer. Orchestrations build on the messaging layer to send and receive the messages used by the business process. Orchestrations are a powerful way to automate complex business processes, but the connectivity and integration benefits come from the underlying messaging components. Nonetheless, there are use cases for BizTalk Server where orchestrations aren't needed, such as in many simple one-way application connectivity scenarios.

It should be no surprise that the messaging architecture is built on an XML foundation. BizTalk Server 2004 can deal with a variety of different message types, but XML is considered the primary or default message type. As a result, BizTalk Server 2004 leverages XML Schema as the primary type system for defining message schemas. And BizTalk Server 2004 provides excellent tool support, integrated with Visual Studio .NET, for working with these XML technologies. XML savvy developers will feel right at home working on this foundation.

A Service-Oriented Foundation

The other thing that really struck me after spending more time with BizTalk Server 2004 was how service-oriented it really is. Most of the folks who promote the tenets of service orientation do so in the context of describing Web services applications and designs. But when you apply the tenets of service orientation to the BizTalk Server architecture, you'll notice an even better fit.

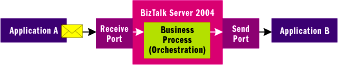

With BizTalk Server, messages are sent and received via ports (see

Figure 2). What happens in between is a complete black box to the sender and receiver. Messages are received by "receive ports" and sent via "send ports." Typically, orchestrations are associated with receive ports and are executed when messages arrive. The orchestration may send a result message (or multiple messages) to another system through send ports.

Figure 2

BizTalk Ports and Messages

Once you have BizTalk Server 2004 installed, you can create and configure ports within the BizTalk Explorer in Visual Studio .NET.

Figure 3 shows how to configure a receive port location (which reads from a file directory on disk) while

Figure 4 shows how to configure a send port (which transmits to an FTP site). Each one configures the transport (adapter) that will be used along with the address where messages will be sent and/or received.

Figure 3

Configuring a Receive Port Location

Once the ports are created and configured, consumers who want to integrate with the business process must be informed of the proper message types to send to the receive ports and the message types they will receive back from send ports. With BizTalk Server, this information is shared with consumers using XML Schema, Web Services Description Language (WSDL), and Business Process Execution Language (BPEL) definitions.

Figure 4

Configuring a Send Port

As you can see, BizTalk Server deals directly with explicit boundaries between applications. In many ways, BizTalk Server is the boundary between the various enterprise applications it orchestrates. Orchestrations also have explicit boundaries (for example, you invoke them by sending messages to ports). The participating applications in a BizTalk environment share schema and contract, not implementation details, to negotiate message exchanges. In fact, BizTalk Server itself knows nothing about how the various participating applications were implemented. Participating applications are completely autonomous and black box to BizTalk Server—they could be running on a variety of different platforms and technologies. New enterprise applications can be added to the mix without affecting existing ones since it's simply a matter of configuring a new message exchange. These traits provide you with a model that can adapt to change over time, which is truly the Zen of service orientation.

Publish-Subscribe Engine

One of the key mechanisms behind the BizTalk Server messaging layer is its flexible publish-subscribe engine. At the heart of BizTalk Server is a SQL Server database, referred to as the MessageBox (see

Figure 5). All of the messages that pass through BizTalk Server are temporarily stored in the MessageBox until they are finished being processed. The receive ports have the job of persisting incoming messages to the MessageBox while the send ports have the job of retrieving messages from the MessageBox for transmission.

Figure 5

Publish-Subscribe in Action

The MessageBox is always in the loop, even for simple request/response style operations. Here's a typical scenario: a message enters a receive port and it's saved to the MessageBox. Then BizTalk Server notices that the message arrived and executes the associated orchestration. The orchestration generates a response message, which is then saved back to the MessageBox. Then a send port picks up the new message and transmits it back to the original sender. So the question is how do send ports and orchestrations know whether to respond to messages arriving in the MessageBox?

This is done through message subscriptions. Both send ports and orchestrations define filters to subscribe to messages entering the MessageBox. When a message hits the MessageBox, all known subscriptions are evaluated to identify matches. The message will then be routed to each orchestration or send port with a matching subscription, as you saw in

Figure 5. A single incoming message could be processed by a handful of different orchestrations and send ports. Or you could have a handful of different receive locations (each bound to a different adapter/transport) that receive the same logical message and execute the same orchestration.

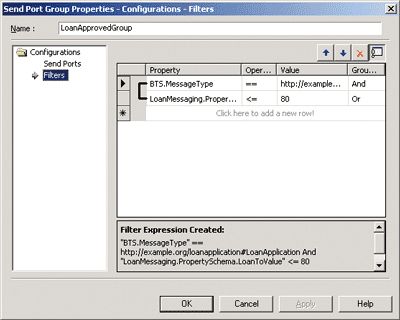

Subscriptions are basically filter expressions that return a Boolean result when evaluated. You can use logical ANDs and ORs to group multiple filter expressions together.

Figure 6 shows an example of two filter expressions—one that matches the message type (the namespace name plus the local name) and another that checks a value from the message body. Each filter expression is evaluated against the incoming message's context, which can contain a variety of information. It typically contains some BizTalk-specific information (such as port details) along with information propagated from the transport, and any properties promoted from the message body itself.

Figure 6

Defining Filter Expressions (Subscriptions)

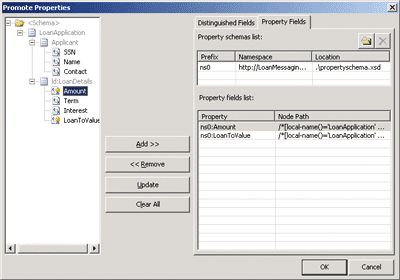

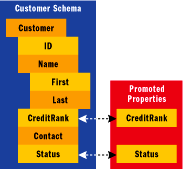

Developers promote nodes in the message schema that they want to make visible to the message context.

Figure 7 illustrates how this is done using the Promote Properties dialog accessible from the BizTalk Schema Editor. Once promoted, information about the properties is stored in the schema definition so BizTalk knows what to promote when messages arrive at run time. The promotion process occurs after a message is received by a port but before it's persisted to the MessageBox.

Figure 7

Promoting Properties

You can think of promoted properties as a view over the entire message as in a SQL view (see

Figure 8). This view only needs to contain the information that you need for routing and decision purposes. This makes it possible for BizTalk Server to optimize message processing, which is helpful with large messages.

Figure 8

Message Properties

This publish-subscribe mechanism makes the messaging layer asynchronous by nature. Synchronous request/response style operations are possible but they're still implemented around the centralized MessageBox in an asynchronous way, which means you'll never achieve the same speeds as traditional synchronous communications. The publish-subscribe mechanism decouples senders from receivers and allows new participants to be added at any point without affecting the existing ones. It also enables some sophisticated content-based routing possibilities through promoted properties.

Contract-Driven Messaging

Now that I've covered the major pieces of the messaging architecture, let's review the high-level development process. Developers typically start by modeling the messages that will flow through their system across the various applications. These messages are defined using XML Schema via the BizTalk Schema Editor. Developers then promote the message properties that will be used for routing or decision purposes. The promotions found in the schema-based contracts are then used by the messaging components to populate the message context at run time and evaluate message subscriptions. Developers can then configure send ports or orchestrations to subscribe to messages matching criteria related to these properties.

As you can see, the entire development process starts with the original schema definitions and everything builds on that. The schema-based contracts dictate how messages are processed, how subscriptions are evaluated, and ultimately how messages flow through the system. They really lay the foundation for the entire solution. It's truly an example of contract-driven messaging at its finest.

Port Extensibility

Throughout this article, I've focused on the BizTalk Server 2004 approach to XML messaging and some of the basic architectural principles that make it all work. I've also highlighted various aspects of the BizTalk Server 2004 architecture that have resonated with me as an XML developer. But this is only the tip of the iceberg.

Figure 9

Port Internals

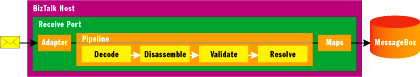

In addition to what I've covered here, BizTalk Server 2004 provides some powerful extensibility points that allow you to perform additional processing while a message is being received but before it's persisted to the MessageBox (see

Figure 9). It also provides the same extensibility points when messages leave the MessageBox. The three port extensibility points are adapters, where bytes are read; pipelines, where preprocessing is performed in stages; and maps, where the message can be transformed, as shown in

Figure 9. XML developers will find these extensibility points particularly interesting due to the flexibility they introduce and the common problems they help solve. I'll cover port internals in detail in the next installment of this column.

Wrap-Up

BizTalk Server has changed dramatically over the years, maturing from its humble beginnings into something more useful and applicable than many developers imagined possible. The current version has many gems for the XML developer better tools and automated support for some of the most common XML integration tasks. BizTalk Server provides a message-oriented approach to connecting systems, something that's truly service-oriented by design. In Part 2 of this series, I'll dive into the port extensibility points including adapters, pipelines, and maps. But while you're waiting, check out "

Understanding BizTalk Server 2004", "

BizTalk Server 2004: A Messaging Engine Overview", and

Pluralsight's BizTalk Wiki.

In my last column, I provided a brief introduction to BizTalk

® Server 2004 for XML developers (see

Service Station: An XML Guru's Guide to BizTalk Server 2004, Part I). I covered the product evolution, core architecture, and several aspects of the underlying messaging layer, all of which have helped make BizTalk Server 2004 the powerful integration technology it is today. I wrapped up after introducing the various extensibility points offered by the messaging layer. These extensibility points are where most of the valuable XML nuggets reside. This month I'll discuss these concepts in more detail. Note that everything I'm discussing is also relevant to the new BizTalk Server 2006.

The Journey of a Message

As I discussed in Part 1 of this column, a message enters BizTalk Server 2004 through a receive port. The job of a receive port is to process the incoming bytes and then to publish the resulting message to the MessageBox.

The MessageBox is, in many ways, the heart of BizTalk Server 2004. All messages passing through the system are persisted to the MessageBox for processing. In addition to holding transient messages, the MessageBox holds subscription information that directs what happens when messages arrive. You create subscriptions either explicitly through BizTalk Explorer in Visual Studio

® .NET (that is, via a send port filter) or implicitly through the orchestration designer (via Receive shapes). Hence, there are two primary types of message subscribers: send ports and orchestrations.

When a message hits the MessageBox, the subscriptions are evaluated to determine which ones match, and each matching subscription is activated. When an incoming message matches a send port subscriber, the message is simply sent out through the given send port. When an incoming message matches an orchestration subscriber, the orchestration is either activated (when it's not already running) or in the case of a running orchestration, the message is simply routed back to the existing orchestration instance (such as when an orchestration is waiting for a response message to return).

To sum it up, messages enter the system through receive ports and leave the system through send ports, potentially passing through orchestration instances along the way. Let's look at a simple scenario in which BizTalk Server 2004 can be used to connect the dots between a few disparate applications.

Using Ports to Connect the Dots

Assume that you need to connect a legacy application with a few new apps. The legacy system was designed to periodically spit out a batch file containing orders that the new applications need to process. One of the new applications was designed to receive orders through a particular FTP site while the other application was designed to receive them through a Microsoft

® Message Queue (MSMQ). There are many ways you could write the code to connect these systems. But to do it right, you'll have to deal with multicasting, a variety of protocols, possible network problems, retry attempts, backup plans, and differences in message formats, so it isn't as simple as it first sounds.

Luckily, this is exactly the type of integration scenario BizTalk Server 2004 was designed to solve. And you can accomplish the integration without writing a single line of code. Just configure a few ports and you're finished. You're basically putting BizTalk Server 2004 between the legacy application and the new apps in what integration specialists typically refer to as a "hub and spoke" configuration. BizTalk Server 2004 becomes the hub and the various disparate applications are the spokes. In such a configuration, only the hub needs to understand all of the protocols used by the various spokes. Then any one spoke can talk to any other by relaying the message through the hub.

In order to accomplish this kind of protocol translation with BizTalk Server 2004, you first create a new receive port. You can do this in Visual Studio .NET by selecting Add Receive Port in BizTalk Explorer. In this case you need a one-way port (which I'll call OrderBatchReceivePort).

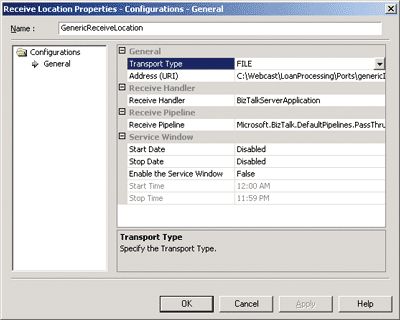

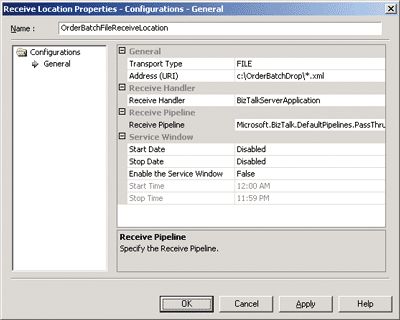

Once the receive port is created, you need to create a receive location and configure it to pick up the order batch file produced by the legacy application. The dialog for creating a receive location is shown in

Figure 1. You'll give the receive location a name, choose a transport type, and specify an address. For this example you need to use the FILE transport type. If you click the button next to the Address field, you'll see a dialog box for entering address details. The configuration I've used tells the receive location to listen for all .xml files in the \\devserver\OrderBatchDrop network share, as I've entered that path in both the Receive folder and Public address fields. It also tells BizTalk to retry every five minutes for a total of five tries if the network share is unavailable because I entered the value 5 into Retry Count and Retry Interval boxes.

Figure 1

Configuring a New Receive Location

At this point you also need to choose a receive pipeline that will be used to process the incoming messages before they're published to the MessageBox. In this case I'll choose the built-in PassThruReceive pipeline, which doesn't do any special processing. It just passes the message through to the MessageBox.

Once you've created a receive location, it will show up in BizTalk Explorer. Then you need to right-click on the receive location and select Enable to have it begin listening for incoming files. Once you do that, your new receive location will begin picking up all .xml files written to the \\devserver\OrderBatchDrop share and publishing them to the MessageBox. However, if you do it at this point, an error will be written to the event log stating that no subscriptions were found for the incoming message.

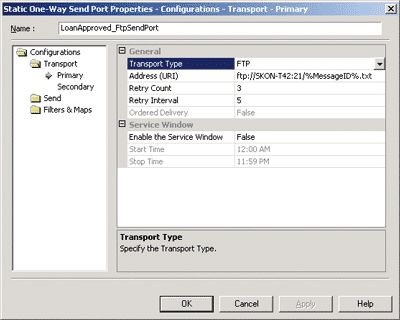

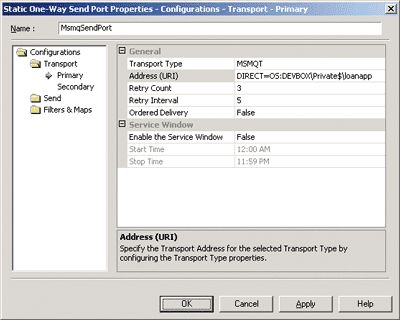

Now you need to configure the send ports—they will be the subscribers in this case. This can be done by selecting Add Send Port in BizTalk Explorer and configuring it much like you did for the receive port. One of the main differences between send and receive ports is that send ports don't contain send locations. You configure the transport details right on the send port itself. For this example you'll need two one-way send ports. One needs to be configured for FTP and the other for the BizTalk Message Queuing Adapter (MSMQT), the BizTalk Server implementation of the MSMQ wire protocol.

Figure 2 serves as an example of the configuration settings.

Figure 2

Configuring a New Send Port (MSMQ)

Note that the addresses are configured for each send port. One is an FTP address (not shown) while the other is specific to MSMQ (as shown in

Figure 2). The FTP address includes a file name of %MessageID%.xml, which tells BizTalk to generate a new file name using a unique message identifier when sending the file to the FTP location. With send ports, you also specify retry information as well as a secondary transport to use when the retry attempts fail. And you must specify a send pipeline (which I'll discuss later), which will be used to process the message after it's read from the MessageBox, but before it's transmitted to the send port address. I'll use the PassThruTransmit pipeline for now.

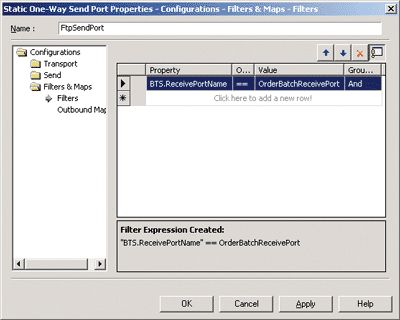

Now you need to define subscription information for both of these send ports, so BizTalk knows that they need to be used whenever messages come in through the OrderBatchReceivePort. You do this by defining "filters" on the send port, as shown in

Figure 3. The filter expression (BTS.ReceivePortName = = OrderBatchReceivePort) states that if the message entered the system via a receive port named "OrderBatchReceivePort," you have a match. You need to use this same filter expression on both send ports so they are both used for each message that hits the receive location. This is a situation in which you could also use a send port group so you only have to specify the filter expression once. When you're finished configuring the send ports, right-click on them in BizTalk Explorer and select Start. Doing so writes the send port subscription information to the MessageBox and enables them for use.

Figure 3

Configuring a Filter Expression (Subscription)

With this configuration in place, the legacy application can now drop arbitrarily named XML files into the \\devserver\OrderBatchDrop network share, at which point BizTalk Server 2004 will read the file from the network share and publish the contents to the MessageBox. When the message hits the MessageBox, the subscriptions are evaluated and, in this case, both send ports are activated. This causes the message to be sent to the FTP site and MSMQ queue, which are the integration points for the new applications, as illustrated in

Figure 4.

Figure 4 BizTalk Integration Scenario

Figure 4 BizTalk Integration Scenario

Notice that you did not need an orchestration to solve this integration scenario, although you might choose to use one when you need more sophisticated error handling logic beyond what's provided by ports. Also notice that I have not performed any special message processing at this point. Since I used the "PassThru" pipelines, the messages simply pass through the system unchanged. It's likely you'll need to perform message transformations during the integration process. I've essentially used ports to connect the dots between these disparate applications at a protocol level. It's interesting to note that this type of integration would not have been possible using Web services alone, at least not without modifying the legacy application to some degree. This integration is accomplished by sending messages through a hub capable of speaking a variety of different dialects.

Port Internals

There is actually much more to a port than first meets the eye. As I walked through the integration scenario, I largely ignored message processing needs and focused on connecting the dots across different protocols. Message processing is a big part of what happens within a port, enabling you to inject code to process or to reshape messages as they pass through the system. This occurs right after a message is received and before it's published to the MessageBox. And, it also occurs after a message is read from the MessageBox but before it's transmitted.

A port primarily consists of an adapter, a pipeline, and a set of maps. Each piece focuses on a different aspect of message processing. Adapters deal with transport details and reading bytes. Pipelines are responsible for performing message processing in stages—they deal with things like message encoding/decoding, message context, validation, and security. A map is simply a transform that defines how to move data from one message schema into another. I'll discuss all three in more detail shortly.

When receiving messages through a receive location, the adapter does its job first, followed by the receive pipeline, and then finally the maps are applied. The resulting message is then published to the MessageBox. The same process is used when sending messages through a send port, except in reverse. The maps are applied first, followed by the send pipeline, and then the adapter transmits the resulting bytes using the specified transport.

On the receive side, you configure the adapter and pipeline on the receive location, but you configure the set of maps on the receive port itself (this allows you to have multiple receive locations that all use the same set of maps). However, on the send side, you configure all three on the send port (you can't configure maps on a send port group,as you might imagine).

As a developer, these three areas are your primary extensibility points for message processing.

Messages

Before diving into adapters, pipelines, and ports, it's important to first understand what messages are in BizTalk Server 2004 and how they are dealt with. When an external message enters the system through a receive location, BizTalk constructs a message that is used internally from that point on. The message is actually considered a multipart message, where each part can be of a different type (XML, flat file, serialized .NET Framework class, and so on). In the most common case, a message contains a single part of XML.

Once messages are constructed, they become immutable. This means that other components cannot modify the message directly. They can, however, construct a new message and populate it with data from another message, which is very common.

Messages also have a context associated with them while in the system. This is a very important concept in BizTalk Server 2004 as it's your only interface to the message during processing. You can think of the message context as the view of the message available to you at run time. For example, only the message context is available to you when writing filter expressions or orchestration logic—you don't have access to the entire message at those points. Some message context properties are related to transport details, others to BizTalk concepts (such as receive port names and IDs), and others come from the content of the message. You control what goes in the message context by promoting properties in your schemas during design.

Messages are the focal point in BizTalk. Adapters, pipelines, and maps all deal with them directly as do orchestrations.

Adapters

A BizTalk adapter is a piece of .NET code that implements a particular transport protocol and knows how to integrate with the rest of the BizTalk infrastructure. Adapters are used to both send and receive messages. A send adapter's primary job is to pump the bytes it receives through the transport. A receive adapter's primary job is to read the incoming bytes from the transport and to construct a BizTalk message. It's also responsible for creating the initial message context and populating it with some basic information, including transport and receive location details. After the message is constructed, it's handed off to the receive pipeline.

In the integration scenario presented earlier, I used the FILE adapter to receive the order batch file from a network share and the FTP and MSMQ adapters to send the message to different locations. BizTalk Server 2004 ships with several adapters in the box including EDI, FILE, FTP, HTTP, MSMQT, SMTP, SOAP, and SQL. These will show up in the Transport Type list in the various configurations screens.

These built-in adapters provide for some of the most common communication cases, but the BizTalk adapter framework allows for new adapters to be introduced at any point in time. Microsoft has shipped several downloadable adapters since the release of BizTalk Server 2004 (see

Microsoft BizTalk Server 2004 Adapters). This list includes adapters for Web Services Enhancements (WSE) 2.0, MSMQ, WebSphere MQ v2.0, mySAP Business Suite, and even a community drop of a Windows Communication Foundation Beta 1 adapter.

But what's most impressive is how the BizTalk adapter framework has fostered a healthy third-party community. Check out the long list of available partner adapters, which covers almost everything available today, at

BizTalk Partner Adapters 2004. It's primarily this healthy collection of adapters that makes BizTalk so compelling from an integration perspective.

And if that isn't enough for your needs, you can always write a custom adapter that can be plugged into the system. This is typically left to the integration vendors as it's not for the faint of heart. Adapters deal with low-level protocols and communication details, which is not where most developers want to spend their time. Most just choose an existing adapter and configure it to fit their particular needs. Pipelines are the main extensibility point for message processing.

Pipelines

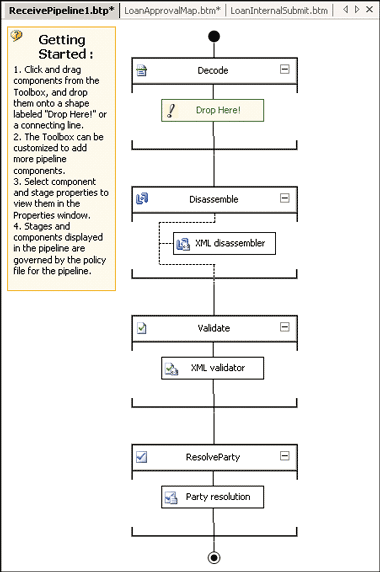

I've mentioned the BizTalk pipelines already and you are probably wondering what they are, so let's take a look. A BizTalk pipeline is a .NET-based component that performs pre- and post-processing on a BizTalk message. There are two types of pipelines: receive pipelines and send pipelines. You can think of a pipeline as a skeleton for common processing stages that occur when sending or receiving messages. Receive pipelines have four stages: decode, disassemble, validate, and resolve party. Send pipelines have three stages: pre-assemble, assemble, and encode. You can add components to perform message processing during any of these stages.

You design pipelines in Visual Studio .NET using the BizTalk pipeline designer. The designer allows you to drag pipeline components from the toolbox into the different stages of interest (see

Figure 5). BizTalk Server 2004 ships with several default pipeline components, which cover some of the most common message processing tasks. These will show up in the pipeline designer toolbox. You can also write custom pipeline components that can be used here.

Figure 5

XML Validation Pipeline

There are a few default pipelines that are already preconfigured and ready to use when you install BizTalk Server 2004. There are two receive pipelines, XMLReceive and PassThruReceive, and two send pipelines, XMLTransmit and PassThruTransmit. The PassThru pipelines don't do anything; in other words, they don't contain any pipeline components.

The default XMLReceive pipeline uses the XML Disassembler component (as well as the Party Resolution component). The XML Disassembler component looks for the XML Schema Definition (XSD) corresponding to the incoming message and then uses it to parse the message and to build the message context according to the promotions found in the schema. (A common error when using BizTalk Server 2004 is to use this component without deploying the XSD schemas it needs to function.)

This pipeline does not perform XSD validation by default. However, if you want to enable XSD validation, you can create a new receive pipeline and drag the XML Disassembler component to the Disassemble stage, the Party Resolution component to the ResolveParty stage, and the XML Validator component to the validate stage (see

Figure 5). Your new receive pipeline will be equivalent to XMLReceive but with XSD validation enabled. I love how easy it is to incorporate XSD validation into your message processing without writing any code.

The default XMLTransmit pipeline only contains a single component, the XML Assembler, which focuses primarily on transferring properties from the message context back into the document and serializing it for transmission.

In my integration scenario, it's likely that the legacy application doesn't produce XML, but rather some proprietary flat file format. In cases like these, you can design pipelines that use the Flat File Assembler/Disassembler components. With these components, you specify the XSD schema that contains the information about how to map the flat file format to an internal XML format, and the components make it happen (in either direction). You'll design the specific flat file translation information into your XSD schemas using the BizTalk Schema Editor.

The receive pipeline is where the message context is built and populated. So if you ever need to get special stuff in the message context (that isn't automatically provided elsewhere), this is where you want to do it. You'll need to write a pipeline component that promotes the information into the context during the Disassemble stage. Writing custom pipeline components is probably the most common place you'll inject .NET code within the messaging layer. And the beauty of this model is that once you've developed pipeline components, all your developers can take advantage of them in a declarative manner using the pipeline designer.

Maps

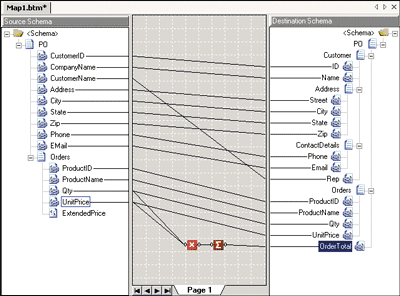

After a message comes out of a receive pipeline, you can apply maps to it. A map is essentially an XSLT transformation that reshapes the message into a different XML format. You design maps using the BizTalk Mapper, which is integrated with Visual Studio .NET (see

Figure 6). The BizTalk Mapper is a wonderful tool that takes the pain out of XSLT. It allows you to open the source and destination XSD schemas and then you typically just drag lines between them in order to specify how the data should map over.

Figure 6

Map for Transforming Between Order Schemas

This technique works well in simple scenarios where you mostly have a 1-to-1 mapping. But in more complex scenarios, you'll need to utilize functoids in your maps. A functoid is a special component that executes some code during the XSLT transformation (the red squares in

Figure 6).

BizTalk Server 2004 ships with numerous functoids that you'll find in the BizTalk Mapper toolbox. There is also a special Scripting functoid that allows you to embed .NET code or XSLT templates directly into the map. It also allows you to call out to external .NET assemblies if you need some help from imperative code along the way. And if that isn't enough to satisfy your extensibility cravings, you can also write custom functoids that can be deployed and used by all the developers on your team when designing new maps (similar to pipeline components).

Since BizTalk maps are simply XSLT, you can author them using the XSLT tool of your choice and then bring them into your BizTalk solution. However, the BizTalk mapping tools are some of the most user-friendly tools I've used, which makes it hard to find a reason to look elsewhere.

In general, the mapping layer makes it simple to address tough integration issues at the message level. Going back to my integration scenario, it's likely that each of the new applications require a different XML dialect. You can solve this by using a receive pipeline to disassemble the flat file into an internal XML message format. Then you can design two maps, one for moving between the internal schema and each schema required by the new applications. Then you simply apply those maps to the send ports.

Maps are also commonly used within receive ports to normalize different external document formats that you need to support (from different customers or application versions, for instance) into a single internal message format that you've built your business process around. Maps can also be used within orchestrations to move between different message formats as needed by the business process.

The BizTalk mapping layer is one of the product's crown jewels, and combined with the adapter framework, it becomes very compelling. I've met several customers who use BizTalk Server 2004 strictly for these powerful XML messaging components alone.

Where Are We?

You can use BizTalk Server 2004 in a variety of configurations to connect your systems without much code. It's truly fit to become your infrastructure duct tape once you understand how it works. It can provide a quick fix to tough integration problems at both the protocol and message level. If you added yet another new application to the integration scenario I presented here, and this one was built using WSE 2.0 with various WS-Security features, you could easily integrate the legacy application with the fancy new WSE 2.0 endpoint through yet another send port. The connectivity possibilities are endless.

In this two-part series on BizTalk Server 2004, I've discussed the overall architecture and core messaging components that bring XML to life in some pragmatic and flexible ways. The BizTalk Server 2004 messaging layer provides powerful connectivity and integration benefits when building connected systems in the real world where legacy applications abound. But it's the ability to deal with legacy as well as new Web service infrastructure that makes BizTalk Server 2004 a compelling XML platform to build on long term.

If you'd like some resources to explore, check out

Understanding BizTalk Server 2004,

BizTalk Server 2004: A Messaging Engine Overview, and my

BizTalk Wiki.

Send your questions and comments for Aaron to [email protected].