- 通过浏览器扩展获取本机 MAC 地址

云水木石

macos

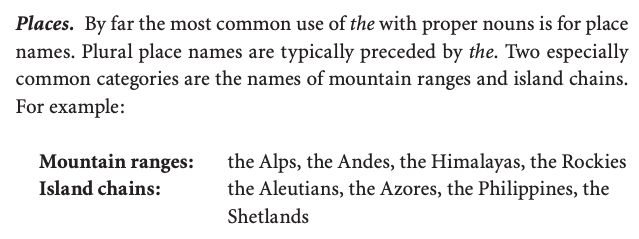

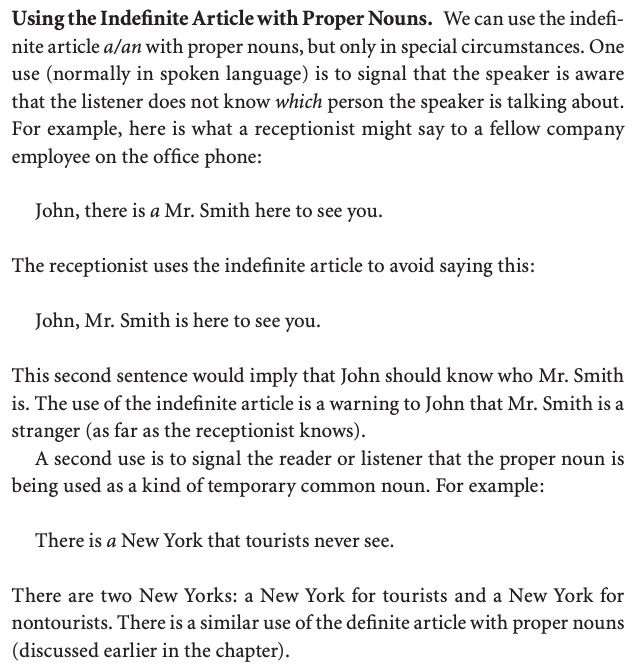

在Web技术主导的B/S架构项目中,获取终端设备硬件信息(如MAC地址)的需求经常会碰到。尽管Electron/CEF等混合应用框架可通过系统级API轻松实现,但纯浏览器环境下的硬件信息获取则不那么容易。因为现代浏览器基于沙箱机制和隐私保护策略,严格禁止网页直接访问底层硬件资源。但用户的需求不能不考虑,特别是在做商业项目时,这时就不得不给出方案,总结下来有如下三种方案:扩展JSAPI:比如以前在做

- access读取EXCEL文件,并根据动态生成表,完成报表的导入

MES先生

ACCESSVBAaccess

OptionCompareDatabasePublicsheetidAsString'报表IDPublictempAsString'获取年月时分秒PublictmpIAsInteger'对应EXCEL行PublictmpJAsInteger'对应EXCEL列PublicXlsAppAsObjectPublicXlsWorkbookAsObjectPublicXlsWorkSheetAsObject

- leetcode-hot100-python-专题三:滑动窗口

༺ Dorothy ༻

leetcodehot100leetcodepython算法

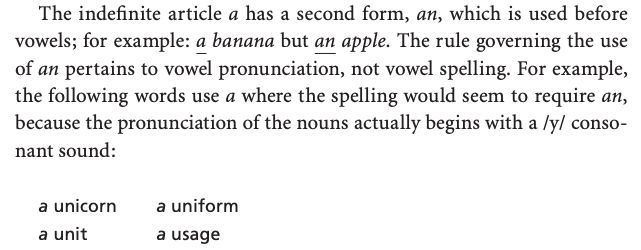

1、无重复字符的最长子串中等给定一个字符串s,请你找出其中不含有重复字符的最长子串的长度。示例1:输入:s=“abcabcbb”输出:3解释:因为无重复字符的最长子串是“abc”,所以其长度为3示例2:输入:s=“bbbbb”输出:1解释:因为无重复字符的最长子串是“b”,所以其长度为1。示例3:输入:s=“pwwkew”输出:3解释:因为无重复字符的最长子串是“wke”,所以其长度为3。请注意,

- Golang算法(二)数据结构

小烧卖

算法GO语言

数据结构栈队列双向链表二叉搜索树红黑树栈typeStackstruct{head*Node}typeNodestruct{datainterface{}next*Node}funcNewStack()*Stack{s:=&Stack{head:&Node{data:nil,next:&Node{},},}returns}func(s*Stack)Push(datainterface{}){n:=&

- Android 中蓝牙Profile与UUID

jaylkh

androidbluetooth

在Android中,常用的几种BluetoothProfile分别为:SPP(SerialPortProfile)、A2DP(AdvancedAudioDistributionProfile)、AVRCP(Audio/VideoRemoteControlProfile)、HID(HumanInterfaceDeviceProfile)、HFP(Hands-FreeProfile)。其中Media相

- 使用kubeadm部署高可用IPV4/IPV6集群---V1.32

使用kubeadm部署高可用IPV4/IPV6集群https://github.com/cby-chen/Kubernetes开源不易,帮忙点个star,谢谢了k8s基础系统环境配置配置IP#注意!#若虚拟机是进行克隆的那么网卡的UUID和MachineID会重复#需要重新生成新的UUIDUUID和MachineID#UUID和MachineID重复无法DHCP获取到IPV6地址sshroot@1

- 某人想将手中的一张面值100元的人民币换成10元、5元、2元和1元面值的票子。要求换正好40张,且每种票子至少一张。问:有几种换法?(C语言)

热心市民小汪

代码练习C语言c语言学习java

一、首先分析题目有两点1、总和是100元。2、一共分为四十张且每种至少有一张。二、思路分析。10元的为s张,5元的为w张,2元的为e张,1元的为y张。n为有几种换算法首先,每个至少有一张a>=1,b>=1,c>=1,d>=1。#includeintmain(){inttotal;for(ints=1;s<=10;s++){for(intw=1;w<=20;w++){for(inte=1;e<=40

- 求第k趟冒泡排序的结果

C嘎嘎嵌入式开发

算法算法数据结构排序算法

冒泡排序基本思想:重复地走访要排序的元素列,依次比较相邻的两个元素,如果顺序错误就交换它们,直到没有元素需要交换。时间复杂度:最坏和平均情况都是O(n²)。空间复杂度:O(1),属于原地排序。稳定性:稳定。求第k趟冒泡排序的结果voidsolve(){intn,k;cin>>n>>k;vectorv(n);for(inti=0;i>v[i];}if(k>n-1){//n个元素最多需要n-1趟排序s

- 基于AWS Endpoint Security(EPS)的自动化安全基线部署

weixin_30777913

云计算awspython安全架构

设计AWS云架构方案实现基于AWSEndpointSecurity(EPS)的自动化安全基线部署,AMSAdvanced(AWS托管服务)环境会为所有新部署的资源自动安装EPS监控客户端,无需人工干预即可建立统一的安全基线。这种自动化机制特别适用于动态扩缩的云环境,确保新启动的EC2实例、容器等终端设备从初始状态即受保护,以及具体实现的详细步骤和关键代码。以下是基于AWSEndpointSecur

- 聊聊langchain4j的Naive RAG

hello_ejb3

人工智能

序本文主要研究一下langchain4j的NaiveRAG示例publicclassNaive_RAG_Example{/***ThisexampledemonstrateshowtoimplementanaiveRetrieval-AugmentedGeneration(RAG)application.*By"naive",wemeanthatwewon'tuseanyadvancedRAGte

- 常见的编码方式及特征

菜根Sec

服务器网络linuxweb安全网络安全

一、BASE编码1、Base64Base64是网络上最常见的用于传输8Bit字节码的编码方式之一,Base64就是一种基于64个可打印字符来表示二进制数据的方法。Base64,就是包括小写字母a-z、大写字母A-Z、数字0-9、符号"+“、”/"一共64个字符的字符集。(1)编码规则①把3个字节变成4个字节。②每76个字符加一个换行符。③最后的结束符也要处理(2)举例说明转前:s13先转成asci

- 有奖直播 | NXP S32K31X 系列 ASIL-B 车身应用方案介绍

WPG大大通

研讨会大大通研讨会汽车车身控制芯片智能

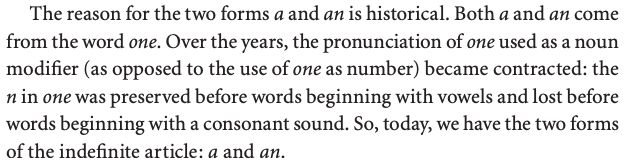

随着汽车智能化、电动化的快速发展,车身控制模块(BCM)作为汽车电子系统的核心组成部分,正面临着更高的功能安全要求和更复杂的系统集成需求。NXPS32K31X系列微控制器凭借其高性能、低功耗和符合ASIL-B功能安全等级的特性,成为车身控制应用的理想选择。本次研讨会将深入探讨S32K31X系列在车身控制中的应用方案,帮助开发者快速掌握相关技术,缩短产品开发周期。研讨会内容包含:一、S32K31X系

- vant官网-vant ui 首页-移动端Vue组件库

embelfe_segge

面试学习路线阿里巴巴android前端后端

Vant是有赞前端团队开源的移动端vue组件库,适用于手机端h5页面。鉴于百度搜索不到vant官方网址,分享一下vant组件库官网地址,方便新手使用vant官网地址https://vant-contrib.gitee.io/vant/#/zh-CN/通过npm安装在现有项目中使用Vant时,可以通过npm或yarn进行安装:#Vue2项目,安装Vant2:npmivant-S#Vue3项目,安装V

- LeetCode剑指offer题目记录3

t.y.Tang

LeetCode记录学语言c++leetcode哈希算法

leetcode刷题开始啦,每天记录几道题.目录剑指offer05.替换空格题目描述思路pythonC++剑指offer06.从尾到头打印链表题目描述思路1python思路2pythonC++剑指offer05.替换空格题目描述让我们实现一个函数,把字符串s中的每个空格替换为%20.思路这个题目我只能想到遍历,在空间控制上应该有原地修改的办法会省一些.python如果用python,那直接用spl

- Matlab绘制台风路径--数据来源:中国气象局热带气旋资料中心

e决

matlab

%读取台风数据fid=fopen('CH2009BST.txt','r');data=textscan(fid,'%s','Delimiter','\n');fclose(fid);data=data{1};%提取台风Morakot数据typhoon_data=[];is_dora=false;fori=1:length(data)line=data{i};%检查是否是Morakot台风的起始行i

- SQL数据更新

小王Jacky

数据库学习sql数据库

1.插入数据**(1)插入单个元组**--向学生表S插入一条学生记录INSERTINTOS(SNO,SN,SEX,AGE,DEPT)VALUES('S001','张三','男',20,'计算机系');--向选课表SC插入一条选课记录INSERTINTOSC(SNO,CNO,SCORE)VALUES('S001','C001',85);**(2)插入多个元组**--向课程表C插入多条课程记录INSE

- 【Html+CSS】3D旋转相册

小木荣

web前端csshtml3d

3D旋转木马相册&3D盒子相册因为代码大部分相同,就放一起了注释一下就是另一个相册3D旋转木马相册body{background-color:#000;/*视距,使子元素获得视距效果*/perspective:900px;}section{margin:20vhauto;position:relative;width:200px;height:200px;/*开启3D空间*/transform-s

- Sklearn.model_selection.GridSearchCV

kakak_

MachineLearning

sklearn.model_selection.GridSearchCV具体在scikit-learn中,主要是使用网格搜索,即GridSearchCV类。estimator:即调整的模型param_grid:即要调参的参数列表,以dict呈现。cv:S折交叉验证的折数,即将训练集分成多少份来进行交叉验证。默认是3,。如果样本较多的话,可以适度增大cv的值。scoring:评价标准。获取最好的模型

- Emacs和SML的安装和使用

weixin_42281226

emacs编辑器

环境:Mac电脑参考文章:编程语言软件安装和使用:SML和Emacs1.Emacs安装和基本使用从官网EmacsForMacOSX下载最新版本,正常安装即可。Emacs使用组合键进行操作(组合键比较难记,可以先尝试通用键)。最重要的操作:(C表示Control)C-xC-c:退出EmacsC-g:取消当前操作C-xC-f:打开文件或新建文件C-xC-s:保存文C-xC-w:等同于saveasC-s

- nginx-部署Python网站项目

skyQAQLinux

pythonlinuxnginx服务器

一、部署Python网站项目实验要求配置Nginx使其可以将动态访问转交给uWSGI安装Python工具及依赖1)拷贝软件到proxy主机[root@server1~]#scp-r/linux-soft/s2/wk/python/192.168.99.5:/root2)安装python依赖软件[root@proxy~]#yum-yinstallgccmakepython3python3-devel

- LabVIEW通过以太网与S PLC通信

JwxDjango

labview信息与通信

LabVIEW是一种强大的工程开发平台,广泛应用于自动化和控制系统。它提供了丰富的功能和工具,使工程师能够轻松地开发各种应用程序,包括与外部设备的通信。本文将介绍如何使用LabVIEW通过以太网与SPLC进行通信,并提供相应的源代码。在开始之前,确保已安装好LabVIEW开发环境,并且已经连接好了以太网和SPLC。接下来,我们将按照以下步骤进行操作:创建LabVIEW项目:打开LabVIEW开发环

- centos 7 安装docker-compose

1.下载docker-compose#官方推荐(太慢)curl-L"https://github.com/docker/compose/releases/download/1.26.2/docker-compose-$(uname-s)-$(uname-m)"-o/usr/local/bin/docker-compose#国内(更快)curl-Lhttps://get.daocloud.io/do

- facefusion AI换脸软件的本地部署过程记录

kfrealme

人工智能

tags:AI驾驭facefusion我的环境Win10+N卡安装步骤安装Python3.10方案手动安装Python官网下载安装包安装PythonReleasesforWindows|Python.org我的蓝奏云分享https://www.lanzoub.com/i9La81s1o5gb密码:h17b命令行安装1以管理员身份打开「命令提示符」2删除Microsoft官方源wingetsourc

- 多个单片机之间的SPI主从通讯

菜长江

单片机嵌入式硬件

工程文件链接:链接:https://pan.baidu.com/s/1RXp9lw2ZqyglQSwKnw7Siw?pwd=6666提取码:6666工程里面有很多例子都是看B站视频手打的(这次代码只用到了YJSPI文件夹下面的.C和.H文件其余可以忽略),只是验证通讯和配置一,概述1.因为工作是从事PCBA测试软件开发的(上位机),之前做过的很多项目都是一个单片机完成所有功能,做了有段时间了无非就

- python strip()

编号1993

pythonpython

参考:http://www.jb51.net/article/37287.htm###############################s.strip(del):在字符串s的开头结尾处,删除del中存在的字符s.lstrip(del):在字符串s的开头处,删除del中存在的字符s.rstrip(del):在字符串s的结尾处,删除del中存在的字符s='asdf'#前后均有空格s.strip(

- java简单的小程序_编写一个简单的入门java小程序

雷幺幺

java简单的小程序

1.创建一个java程序的步骤a打开editplus软件,选择左上角的file选项,在弹出来的菜单中选择new然后再从弹出来的菜单中选择normaltextb按住ctrl+s快捷键,保存。1选择要保存的位置2给文件命名(以大写的字母开头)3选择文件的后缀,以.java后缀结尾c进行代码的编写,所有字符我们必须都是英文输入状态下的d打开控制台(win+r在弹出左下角的命令行中输入cmd)e找到jav

- 使用Jupyter Notebook进行深度学习编程 - 深度学习教程

shandianfk_com

ChatGPTAIjupyter深度学习ide

大家好,今天我们要聊聊如何使用JupyterNotebook进行深度学习编程。深度学习是人工智能领域中的一项重要技术,通过模仿人脑神经网络的方式进行学习和分析。JupyterNotebook作为一个强大的工具,可以帮助我们轻松地进行深度学习编程,尤其适合初学者和研究人员。本文将带领大家一步步了解如何在JupyterNotebook中开展深度学习项目。一、什么是JupyterNotebook?Jup

- Kubernetes配置全解析:从小白到高手的进阶秘籍

ivwdcwso

操作系统与云原生kubernetes容器云原生k8s配置

导语在Kubernetes(K8s)的世界里,合理且精准的配置是释放其强大功能的关键。无论是搭建集群、部署应用,还是优化资源利用,配置都贯穿始终。然而,K8s配置涉及众多参数与组件,错综复杂,令不少初学者望而却步。本文将带你一步步深入K8s配置领域,从小白进阶为配置高手,轻松驾驭K8s集群。一、Kubernetes集群配置Master节点配置kube-api-server:这是K8s集群的“门面”

- MyBatis——基于MyBatis注解的学生管理程序

基础较差的cs菜鸟

JavaEE实验mybatisjavamysql

MyBatis——基于MyBatis注解的学生管理程序Resourcedao层pojo层utils层测试层实验要求 本实验要求根据学生表在数据库中创建一个s_student表,根据班级表在数据库中创建一个c_class表,班级表c_class和学生表s_student是一对多的关系。实验内容表1学生表(s_student)学生编号(id)学生名称(name)学生年龄(age)所属班级(cid)1

- Python自制文本编辑器

Xiaoqing461

python开发语言

Python自制文本编辑器。随便写的半成品fromtkinterimport*fromtkinterimportfiledialog,messageboxclassFindWindow:def__init__(self,parent):self.parent=parentself.find_window=Toplevel(parent)self.find_window.title("Find")s

- html页面js获取参数值

0624chenhong

html

1.js获取参数值js

function GetQueryString(name)

{

var reg = new RegExp("(^|&)"+ name +"=([^&]*)(&|$)");

var r = windo

- MongoDB 在多线程高并发下的问题

BigCat2013

mongodbDB高并发重复数据

最近项目用到 MongoDB , 主要是一些读取数据及改状态位的操作. 因为是结合了最近流行的 Storm进行大数据的分析处理,并将分析结果插入Vertica数据库,所以在多线程高并发的情境下, 会发现 Vertica 数据库中有部分重复的数据. 这到底是什么原因导致的呢?笔者开始也是一筹莫 展,重复去看 MongoDB 的 API , 终于有了新发现 :

com.mongodb.DB 这个类有

- c++ 用类模版实现链表(c++语言程序设计第四版示例代码)

CrazyMizzz

数据结构C++

#include<iostream>

#include<cassert>

using namespace std;

template<class T>

class Node

{

private:

Node<T> * next;

public:

T data;

- 最近情况

麦田的设计者

感慨考试生活

在五月黄梅天的岁月里,一年两次的软考又要开始了。到目前为止,我已经考了多达三次的软考,最后的结果就是通过了初级考试(程序员)。人啊,就是不满足,考了初级就希望考中级,于是,这学期我就报考了中级,明天就要考试。感觉机会不大,期待奇迹发生吧。这个学期忙于练车,写项目,反正最后是一团糟。后天还要考试科目二。这个星期真的是很艰难的一周,希望能快点度过。

- linux系统中用pkill踢出在线登录用户

被触发

linux

由于linux服务器允许多用户登录,公司很多人知道密码,工作造成一定的障碍所以需要有时踢出指定的用户

1/#who 查出当前有那些终端登录(用 w 命令更详细)

# who

root pts/0 2010-10-28 09:36 (192

- 仿QQ聊天第二版

肆无忌惮_

qq

在第一版之上的改进内容:

第一版链接:

http://479001499.iteye.com/admin/blogs/2100893

用map存起来号码对应的聊天窗口对象,解决私聊的时候所有消息发到一个窗口的问题.

增加ViewInfo类,这个是信息预览的窗口,如果是自己的信息,则可以进行编辑.

信息修改后上传至服务器再告诉所有用户,自己的窗口

- java读取配置文件

知了ing

1,java读取.properties配置文件

InputStream in;

try {

in = test.class.getClassLoader().getResourceAsStream("config/ipnetOracle.properties");//配置文件的路径

Properties p = new Properties()

- __attribute__ 你知多少?

矮蛋蛋

C++gcc

原文地址:

http://www.cnblogs.com/astwish/p/3460618.html

GNU C 的一大特色就是__attribute__ 机制。__attribute__ 可以设置函数属性(Function Attribute )、变量属性(Variable Attribute )和类型属性(Type Attribute )。

__attribute__ 书写特征是:

- jsoup使用笔记

alleni123

java爬虫JSoup

<dependency>

<groupId>org.jsoup</groupId>

<artifactId>jsoup</artifactId>

<version>1.7.3</version>

</dependency>

2014/08/28

今天遇到这种形式,

- JAVA中的集合 Collectio 和Map的简单使用及方法

百合不是茶

listmapset

List ,set ,map的使用方法和区别

java容器类类库的用途是保存对象,并将其分为两个概念:

Collection集合:一个独立的序列,这些序列都服从一条或多条规则;List必须按顺序保存元素 ,set不能重复元素;Queue按照排队规则来确定对象产生的顺序(通常与他们被插入的

- 杀LINUX的JOB进程

bijian1013

linuxunix

今天发现数据库一个JOB一直在执行,都执行了好几个小时还在执行,所以想办法给删除掉

系统环境:

ORACLE 10G

Linux操作系统

操作步骤如下:

第一步.查询出来那个job在运行,找个对应的SID字段

select * from dba_jobs_running--找到job对应的sid

&n

- Spring AOP详解

bijian1013

javaspringAOP

最近项目中遇到了以下几点需求,仔细思考之后,觉得采用AOP来解决。一方面是为了以更加灵活的方式来解决问题,另一方面是借此机会深入学习Spring AOP相关的内容。例如,以下需求不用AOP肯定也能解决,至于是否牵强附会,仁者见仁智者见智。

1.对部分函数的调用进行日志记录,用于观察特定问题在运行过程中的函数调用

- [Gson六]Gson类型适配器(TypeAdapter)

bit1129

Adapter

TypeAdapter的使用动机

Gson在序列化和反序列化时,默认情况下,是按照POJO类的字段属性名和JSON串键进行一一映射匹配,然后把JSON串的键对应的值转换成POJO相同字段对应的值,反之亦然,在这个过程中有一个JSON串Key对应的Value和对象之间如何转换(序列化/反序列化)的问题。

以Date为例,在序列化和反序列化时,Gson默认使用java.

- 【spark八十七】给定Driver Program, 如何判断哪些代码在Driver运行,哪些代码在Worker上执行

bit1129

driver

Driver Program是用户编写的提交给Spark集群执行的application,它包含两部分

作为驱动: Driver与Master、Worker协作完成application进程的启动、DAG划分、计算任务封装、计算任务分发到各个计算节点(Worker)、计算资源的分配等。

计算逻辑本身,当计算任务在Worker执行时,执行计算逻辑完成application的计算任务

- nginx 经验总结

ronin47

nginx 总结

深感nginx的强大,只学了皮毛,把学下的记录。

获取Header 信息,一般是以$http_XX(XX是小写)

获取body,通过接口,再展开,根据K取V

获取uri,以$arg_XX

&n

- 轩辕互动-1.求三个整数中第二大的数2.整型数组的平衡点

bylijinnan

数组

import java.util.ArrayList;

import java.util.Arrays;

import java.util.List;

public class ExoWeb {

public static void main(String[] args) {

ExoWeb ew=new ExoWeb();

System.out.pri

- Netty源码学习-Java-NIO-Reactor

bylijinnan

java多线程netty

Netty里面采用了NIO-based Reactor Pattern

了解这个模式对学习Netty非常有帮助

参考以下两篇文章:

http://jeewanthad.blogspot.com/2013/02/reactor-pattern-explained-part-1.html

http://gee.cs.oswego.edu/dl/cpjslides/nio.pdf

- AOP通俗理解

cngolon

springAOP

1.我所知道的aop 初看aop,上来就是一大堆术语,而且还有个拉风的名字,面向切面编程,都说是OOP的一种有益补充等等。一下子让你不知所措,心想着:怪不得很多人都和 我说aop多难多难。当我看进去以后,我才发现:它就是一些java基础上的朴实无华的应用,包括ioc,包括许许多多这样的名词,都是万变不离其宗而 已。 2.为什么用aop&nb

- cursor variable 实例

ctrain

variable

create or replace procedure proc_test01

as

type emp_row is record(

empno emp.empno%type,

ename emp.ename%type,

job emp.job%type,

mgr emp.mgr%type,

hiberdate emp.hiredate%type,

sal emp.sal%t

- shell报bash: service: command not found解决方法

daizj

linuxshellservicejps

今天在执行一个脚本时,本来是想在脚本中启动hdfs和hive等程序,可以在执行到service hive-server start等启动服务的命令时会报错,最终解决方法记录一下:

脚本报错如下:

./olap_quick_intall.sh: line 57: service: command not found

./olap_quick_intall.sh: line 59

- 40个迹象表明你还是PHP菜鸟

dcj3sjt126com

设计模式PHP正则表达式oop

你是PHP菜鸟,如果你:1. 不会利用如phpDoc 这样的工具来恰当地注释你的代码2. 对优秀的集成开发环境如Zend Studio 或Eclipse PDT 视而不见3. 从未用过任何形式的版本控制系统,如Subclipse4. 不采用某种编码与命名标准 ,以及通用约定,不能在项目开发周期里贯彻落实5. 不使用统一开发方式6. 不转换(或)也不验证某些输入或SQL查询串(译注:参考PHP相关函

- Android逐帧动画的实现

dcj3sjt126com

android

一、代码实现:

private ImageView iv;

private AnimationDrawable ad;

@Override

protected void onCreate(Bundle savedInstanceState)

{

super.onCreate(savedInstanceState);

setContentView(R.layout

- java远程调用linux的命令或者脚本

eksliang

linuxganymed-ssh2

转载请出自出处:

http://eksliang.iteye.com/blog/2105862

Java通过SSH2协议执行远程Shell脚本(ganymed-ssh2-build210.jar)

使用步骤如下:

1.导包

官网下载:

http://www.ganymed.ethz.ch/ssh2/

ma

- adb端口被占用问题

gqdy365

adb

最近重新安装的电脑,配置了新环境,老是出现:

adb server is out of date. killing...

ADB server didn't ACK

* failed to start daemon *

百度了一下,说是端口被占用,我开个eclipse,然后打开cmd,就提示这个,很烦人。

一个比较彻底的解决办法就是修改

- ASP.NET使用FileUpload上传文件

hvt

.netC#hovertreeasp.netwebform

前台代码:

<asp:FileUpload ID="fuKeleyi" runat="server" />

<asp:Button ID="BtnUp" runat="server" onclick="BtnUp_Click" Text="上 传" />

- 代码之谜(四)- 浮点数(从惊讶到思考)

justjavac

浮点数精度代码之谜IEEE

在『代码之谜』系列的前几篇文章中,很多次出现了浮点数。 浮点数在很多编程语言中被称为简单数据类型,其实,浮点数比起那些复杂数据类型(比如字符串)来说, 一点都不简单。

单单是说明 IEEE浮点数 就可以写一本书了,我将用几篇博文来简单的说说我所理解的浮点数,算是抛砖引玉吧。 一次面试

记得多年前我招聘 Java 程序员时的一次关于浮点数、二分法、编码的面试, 多年以后,他已经称为了一名很出色的

- 数据结构随记_1

lx.asymmetric

数据结构笔记

第一章

1.数据结构包括数据的

逻辑结构、数据的物理/存储结构和数据的逻辑关系这三个方面的内容。 2.数据的存储结构可用四种基本的存储方法表示,它们分别是

顺序存储、链式存储 、索引存储 和 散列存储。 3.数据运算最常用的有五种,分别是

查找/检索、排序、插入、删除、修改。 4.算法主要有以下五个特性:

输入、输出、可行性、确定性和有穷性。 5.算法分析的

- linux的会话和进程组

网络接口

linux

会话: 一个或多个进程组。起于用户登录,终止于用户退出。此期间所有进程都属于这个会话期。会话首进程:调用setsid创建会话的进程1.规定组长进程不能调用setsid,因为调用setsid后,调用进程会成为新的进程组的组长进程.如何保证? 先调用fork,然后终止父进程,此时由于子进程的进程组ID为父进程的进程组ID,而子进程的ID是重新分配的,所以保证子进程不会是进程组长,从而子进程可以调用se

- 二维数组 元素的连续求解

1140566087

二维数组ACM

import java.util.HashMap;

public class Title {

public static void main(String[] args){

f();

}

// 二位数组的应用

//12、二维数组中,哪一行或哪一列的连续存放的0的个数最多,是几个0。注意,是“连续”。

public static void f(){

- 也谈什么时候Java比C++快

windshome

javaC++

刚打开iteye就看到这个标题“Java什么时候比C++快”,觉得很好笑。

你要比,就比同等水平的基础上的相比,笨蛋写得C代码和C++代码,去和高手写的Java代码比效率,有什么意义呢?

我是写密码算法的,深刻知道算法C和C++实现和Java实现之间的效率差,甚至也比对过C代码和汇编代码的效率差,计算机是个死的东西,再怎么优化,Java也就是和C