作者:Marshall Goldsmith

出版社:Crown Business

副标题:Becoming the Person You Want to Be

发行时间:2015年5月19日

来源:下载的 epub 版本

Goodreads:3.95(3236 Ratings)

豆瓣:8.2(125人评价)

概要

Marshall Goldsmith 在书中推荐了一种可以进行「自我教练 self-coaching」的方法,通过寻找到每个人行为背后 Trigger 的机制,继而掌握并利用这种机制,读者可以自己构建起「每日自我提问」的方法,通过较长一段时间的实践建立起受益终身的行为,从而获得令自己满意的成就

作者介绍

Marshall Goldsmith 是一位领导力教练,具体的介绍可以看这个视频:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dnYBbJN4hCc

书中有一段文字我觉得作者有暗示自己对自己的假想:

The question is a mash-up of two bits of guidance I’ve valued over the years, one part Buddhist insight, the other part common sense from the late Peter Drucker.

Twitter: https://twitter.com/coachgoldsmith

个人观点

强烈推荐本书,全书主题清晰,废话很少,我觉得书的内容已经突破了作者「领导力教练」的定位和局限,Trigger 这个理论模型在我看来,是一个系统化和升级版本的「富兰克林行为训练法」,更具有可实施性,善加使用会让你获得受用终身的优良习惯

Marshall Goldsmith 是 Coach 出身,对「提问」自然颇有研究,其中提到的 The Power of Active Questions 感觉是我一直以来忽略的,确实 How meaningful was your day? 是远没有 Did you do your best to find meaning? 有力量的,接下来会调整一下自己在做 Coaching 时候的相关问题

这个象限图对我有一定启发,作者认为「需要但是最不愿意去做的事情」是最有价值的,如同「重要-紧急」象限图里面的「重要但不紧急」是最有价值一样,这两种价值判断的标准可以结合为:「重要不紧急,需要不愿意」,这真心是幸福人生的命门啊~

作者有一处写作手法(或者说排版)我很喜欢,为了论述某个具体的主题需要罗列一系列的观点,然后每个观点用一页的结构简单呈现(而不像传统那样是合在一起不分页的),比如第二章里面介绍自律的15个误区部分:

- If I understand, I will do.

- I have willpower and won’t give in to temptation.

- Today is a special day.

- “At least I’m better than…”

- I shouldn’t need help and structure.

- I won’t get tired and my enthusiasm will not fade.

- I have all the time in the world.

- I won’t get distracted and nothing unexpected will occur.

- An epiphany will suddenly change my life.

- My change will be permanent and I will never have to worry again.

- My elimination of old problems will not bring on new problems.

- My efforts will be fairly rewarded.

- No one is paying attention to me.

- If I change I am “inauthentic.”

- I have the wisdom to assess my own behavior.

摘录

A trigger is any stimulus that reshapes our thoughts and actions. In every waking hour we are being triggered by people, events, and circumstances that have the potential to change us. These triggers appear suddenly and unexpectedly. They can be major moments, like Phil’s concussion, or as minor as a paper cut. They can be pleasant, like a teacher’s praise that elevates our discipline and ambition—and turns our life around 180 degrees. Or they can be counterproductive, like an ice-cream cone that tempts us off our diet or peer pressure that confuses us into doing something we know is wrong. They can stir our competitive instincts, from the common workplace carrot of a bigger paycheck to the annoying sight of a rival outdistancing us. They can drain us, like the news that a loved one is seriously ill or that our company is up for sale. They can be as elemental as the sound of rain triggering a sweet memory.

Triggers are practically infinite in number. Where do they come from? Why do they make us behave against our interests? Why are we oblivious to them? How do we pinpoint the triggering moments that anger us, or throw us off course, or make us feel that all is right in the world—so we can avoid the bad ones, repeat the good ones? How do we make triggers work for us?

Our environment is the most potent triggering mechanism in our lives—and not always for our benefit. We make plans, set goals, and stake our happiness on achieving these goals. But our environment constantly intervenes. The smell of bacon wafts up from the kitchen, and we forget our doctor’s advice about lowering our cholesterol. Our colleagues work late every night, so we feel obliged to match their commitment, and miss one of our kid’s baseball games, then another, then another. Our phone chirps, and we glance at the glowing screen instead of looking into the eyes of the person we love. This is how our environment triggers undesirable behavior.

Because our environmental factors are so often outside of our control, we may think there is not much we can do about them. We feel like victims of circumstance. Puppets of fate. I don’t accept that. Fate is the hand of cards we’ve been dealt. Choice is how we play the hand.

I vividly recall my first decisive behavioral change as an adult. I was twenty-six years old, married to my first and only wife, Lyda, and pursuing a doctorate in organizational behavior at the University of California, Los Angeles. Since high school I had been a follicly challenged man, but back then I was loath to admit it. Each morning I would spend several minutes in front of the bathroom mirror carefully arranging the wispy blond stands of hair still remaining on the top of my head. I’d smooth the hairs forward from back to front, then curve them to a point in the middle of my forehead, forming a pattern that looked vaguely like a laurel wreath. Then I’d walk out into the world with my ridiculous comb-over, convinced I looked normal like everyone else.

When I visited my barber, I’d give specific instructions on how to cut my hair. One morning I dozed off in the chair, so he trimmed my hair too short, leaving insufficient foliage on the sides to execute my comb-over regimen. I could have panicked and put on a hat for a few weeks, waiting for the strands to grow back. But as I stood in front of the mirror later that day, staring at my reflected image, I said to myself, “Face it, you’re bald. It’s time you accepted it.”

That’s the moment when I decided to shave the few remaining hairs on the top of my head and live my life as a bald man. It wasn’t a complicated decision and it didn’t take great effort to accomplish. A short trim at the barber from then on. But in many ways, it is still the most liberating change I’ve made as an adult. It made me happy, at peace with my appearance.

I’m not sure what triggered my acceptance of a new way of self-grooming. Perhaps I was horrified at the prospect of starting every day with this routine forever. Or maybe it was the realization that I wasn’t fooling anyone.

The reason doesn’t matter. The real achievement is that I actually decided to change and successfully acted on that decision. That’s not easy to do. I had spent years fretting and fussing with my hair. That’s a long time to continue doing something that I knew, on the spectrum of human folly, fell somewhere between vain and idiotic. And yet I persisted in this foolish behavior for so many years because (a) I couldn’t admit that I was bald, and (b) under the sway of inertia, I found it easier to continue doing my familiar routine than change my ways. The one advantage I had was (c) I knew how to execute the change. Unlike most changes—for example, getting in shape, learning a new language, or becoming a better listener—it didn’t require months of discipline and measuring and following up. Nor did it require the cooperation of others. I just needed to stop giving my barber crazy instructions and let him do his job. If only all our behavioral changes were so uncomplicated.

During the twelve years he was mayor of New York City, from 2001 to 2013, Michael Bloomberg was an indefatigable “social engineer,” always striving to change people’s behavior for the better (at least in his mind). Whether he was banning public smoking or decreeing that all municipal vehicles go hybrid, his objective was always civic self-improvement. Near the end of his third and final term in 2012, he decided to attack the childhood obesity epidemic. He did so by banning sales of sugary soft drinks in quantities greater than sixteen ounces. We can debate the merits of Bloomberg’s idea and the inequities created by some of its loopholes. But we can all agree that reducing childhood obesity is a good thing. In one small way, Bloomberg was trying to alter the environment that tempts people to overconsume sugary drinks. His rationale was unassailable: if consumers—for example, moviegoers—aren’t offered a thirty-two-ounce soft drink for a few pennies more than the sixteen-ounce cup, they’ll buy the smaller version and consume less sugar. He wasn’t stopping people from drinking all the sugary beverage they wanted (they could still buy two sixteen-ounce cups). He was merely putting up a small obstacle to alter people’s behavior—like closing your door so people must knock before interrupting you.

Personally, I didn’t have a dog in this race. (I am not here to judge. My mission is to help people become the person that they want to be, not tell them who that person is.) I watched Bloomberg’s plan unfold purely as an exercise in the richness of our resistance to change. I love New York. The good citizens didn’t disappoint.

People quickly lodged the “nanny state” objection: where does this Bloomberg fellow come off telling me how to live my life? Local politicians objected because they hadn’t been consulted. They hated the mayor’s high-handed methods. The NAACP objected to the mayor’s hypocrisy in targeting soft drinks while cutting phys ed budgets in schools. So-called “mom and pop” store owners objected because the ban exempted convenience stores such as 7-Eleven, which could put the mom-and-pops out of business. Jon Stewart mocked the mayor because the two-hundred-dollar ticket for illegally selling supersize soft drinks was double the fine for selling marijuana.

And so on. In the end, after a barrage of lawsuits, a judge struck down the law for being “arbitrary and capricious.” My point: even when the individual and societal benefits of changing a specific behavior are indisputable, we are geniuses at inventing reasons to avoid change. It is much easier, and more fun, to attack the strategy of the person who’s trying to help than to try to solve the problem.

People who read my writing sometimes tell me, “It’s common sense. I didn’t read anything here that I don’t already know.” It’s the default critique of most advice books (you may be thinking it right now). My thought is always: “True, but I’ll bet that you read plenty here that you don’t already do.” If you’ve ever been to a seminar or corporate retreat where all attendees agreed on what to do next—and a year later nothing has changed—you know that there’s a difference between understanding and doing. Just because people understand what to do doesn’t ensure that they will actually do it. This belief triggers confusion.

This is how feedback ultimately triggers desirable behavior. Once we deconstruct feedback into its four stages of evidence, relevance, consequence, and action, the world never looks the same again. Suddenly we understand that our good behavior is not random. It’s logical. It follows a pattern. It makes sense. It’s within our control. It’s something we can repeat. It’s why some obese people finally—and instantly—take charge of their eating habits when they’re told that they have diabetes and will die or go blind or lose a limb if they don’t make a serious lifestyle change. Death, blindness, and amputation are consequences we understand and can’t brush aside.

I don’t want to get lost in theory over feedback loops. They’re complex and can be applied to almost anything. Photosynthesis is a feedback loop between the sun and plants. Owners of hybrid cars (like me in my Ford C-Max) are in a feedback loop when they obsessively check their dashboard’s gas consumption display and adjust their driving to maximize gas mileage (they’re called “hypermilers”). The Cold War arms race, with East and West escalating weaponry to match each other, may be the most expensive feedback loop in history.

For our purposes, let’s focus on the feedback loop created by our environment and our behavior.

As a trigger, our environment has the potential to resemble a feedback loop. After all, our environment is constantly providing new information that has meaning and consequence for us and alters our behavior. But the resemblance ends there. Where a well-designed feedback loop triggers desirable behavior, our environment often triggers bad behavior, and it does so against our will and better judgment and without our awareness. We don’t know we’ve changed.

Which brings up the obvious question (well, obvious to me): What if we could control our environment so it triggered our most desired behavior—like an elegantly designed feedback loop? Instead of blocking us from our goals, this environment propels us. Instead of dulling us to our surroundings, it sharpens us. Instead of shutting down who we are, it opens us.

To achieve that, we first have to clarify the term trigger:

A behavioral trigger is any stimulus that impacts our behavior.

Within that broad definition there are several distinctions that improve our understanding of how triggers influence our behavior.

- A behavioral trigger can be direct or indirect.

- A trigger can be internal or external.

- A trigger can be conscious or unconscious.

- A trigger can be anticipated or unexpected.

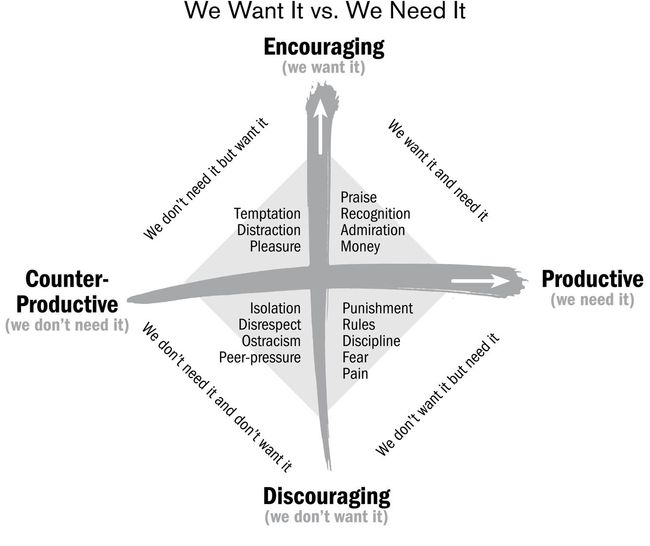

- A trigger can be encouraging or discouraging.

- A trigger can be productive or counterproductive.

We Want It and Need It: The upper right quadrant is where we’d prefer to be all the time. It is the realm where encouraging triggers intersect with productive triggers, where the short-term gratification we want is congruent with the long-term achievement we need. Praise, recognition, admiration, and monetary rewards are common triggers here. They make us try harder right now and they also reinforce continuing behavior that drives us toward our goals. We want them now and need them later.

We Want It but Don’t Need It: The paradoxical effect of an encouraging trigger that is counterproductive comes to a head most tellingly in the upper left quadrant. This is where we encounter pleasurable situations that can tempt or distract us from achieving our goals. If you’ve ever binge-watched a season or two of a TV show on Netflix when you should be studying, or finishing an assignment, or going to sleep, you know how an appealing distraction can trigger a self-defeating choice. You’ve sacrificed your goals for short-term gratification. If you’ve ever taken a supervisor’s compliment or a client’s reassurances as an excuse to ease up a little bit, you know how positive reinforcement can set you back rather than propel you ahead.

We Need It but Don’t Want It: The lower right quadrant is a thorny grab bag of discouraging triggers that we don’t want but that we know we need.

Rules (or any highly structured environment) are discouraging because they limit us; they exist to erase specific behaviors from our repertoire. But we need them because obeying rules makes us do the right thing. Rules push us in the right direction even when our first impulse is to go the other way.

Fear—of shame, punishment, reprisal, regret, disrespect, ostracism—is a hugely discouraging trigger, often appearing after we fail to follow a rule. If you’ve ever been dressed down in public by a high-ranking manager, you know it’s something you don’t want to repeat—which makes it a powerful motivator to stay true to your long-term goals.

Even quirky discipline can be found here. When I fine my clients twenty dollars for cynicism and sarcasm, I’m introducing a discouraging trigger (it’s loss aversion, the concept that we hate losing one dollar more than we enjoy gaining two) that also aims to trigger productive behavior (that is, make people nicer).

Pain, of course, is the ultimate discouraging trigger: we immediately stop a behavior that hurts.

We Don’t Need or Want It: The lower left quadrant, where our triggers are both discouraging and counterproductive, is not a good place to be. It includes all the dead-end situations that make us miserable—and we can’t see any way out of them. It could be a toxic workplace or a violent neighborhood, the kinds of environment that trigger unhealthy behavior steering us away from our goals. There’s not much mystery to why these ugly environments trigger fatigue, stress, apathy, hopelessness, isolation, and anger. The only puzzle is why we choose to stay here instead of fleeing at high speed.

I’m not rigid or doctrinaire about these quadrants. Our experience is too rich and fluid to be contained in a theoretical box. Some triggers overlap or mutate, depending on how we respond, and move us from a bad place to a good one. Consider the triggering impact of peer pressure. An academically ambitious teen may be mocked and ostracized by his slacker classmates for studying hard and wanting to go to college. If he allows the peer pressure to discourage him from his goals, he’ll find himself in the unenviable lower left quadrant. On the other hand, if he resists the peer pressure and endures the ostracism, the isolation may focus him and steel his resolve. It gives him the discipline he needs. It may not be pleasant in the short term but it’s all the push he needs to shift to the lower right quadrant. Same trigger and goals, different responses and outcomes.

I find the grid useful as an analytical tool with my clients. It enables them to take inventory of the triggers in their lives, which, if nothing else, increases their awareness about their environment. More important, it reveals whether they’re operating in a productive quadrant. The right side of the matrix is where successful people want to be, moving forward on their behavioral goals.

Now it’s your turn. Try this modest exercise.

When I was getting my doctorate at UCLA, the classic sequencing template for analyzing problem behavior in children was known as ABC, for antecedent, behavior, and consequence.

The antecedent is the event that prompts the behavior. The behavior creates a consequence. A common classroom example: a student is drawing pictures instead of working on the class assignment. The teacher asks the child to finish the task (the request is the antecedent). The child reacts by throwing a tantrum (behavior). The teacher responds by sending the student to the principal’s office (consequence). That’s the ABC sequence: teacher request to child’s tantrum to hello principal. Armed with this insight, after several repeat episodes the teacher concludes that the child’s behavior is a ploy to avoid class assignments.

In his engaging book, The Power of Habit, Charles Duhigg applied this ABC template to breaking and forming habits. Instead of antecedent, behavior, and consequence, he used the terms cue, routine, and reward to describe the three-part sequence known as a habit loop. Smoking cigarettes is a habit loop consisting of stress (cue), nicotine stimulation (routine), leading to temporary psychic well-being (reward). People often gain weight when they try to quit smoking because they substitute food for nicotine as their routine. In doing so, they are obeying Duhigg’s Golden Rule of Habit Change—keep the cue and reward, change the routine—but they are doing it poorly. Doing thirty push-ups (or anything physically challenging) might be more effective than eating more.

Duhigg provides a terse, vivid example of the cue-routine-reward loop in action—and how we can use it to break a bad habit. A graduate student named Mandy bites her nails, habitually and incessantly until they bleed. She wants to stop. A therapist elicits from Mandy that she brings her fingers to her mouth whenever she feels a little bit of tension in her fingers. The tension appears when she’s bored. That’s the cue: tension in her fingers brought on by boredom. Biting her nails is the routine that fights her boredom. The physical stimulation, especially the sense of completeness when she nibbles all ten nails down to the quick, is Mandy’s reward. She craves it, which makes it habitual.

The therapist instructs Mandy to carry an index card and make a check mark on the card each time she feels the finger tension. A week later she returns to the therapist with twenty-eight check marks on the card, but she is now enlightened about the cues that send her fingers to her mouth. She’s ready to replace her routine. The therapist teaches her a “competing response”—in this case, putting her hands in her pocket or gripping a pencil, anything that prevents her fingers from going to her mouth. Eventually Mandy learns to rub her arms or rap her knuckles on a desk as a substitute for the physical gratification that nail biting provides. The cue and reward stay the same. The routine has changed. A month later, Mandy has stopped biting her nails completely. She’s replaced a harmful habit with a harmless one.

I learned about active questions from my daughter, Kelly Goldsmith, who has a Ph.D. from Yale in behavioral marketing and teaches at Northwestern’s Kellogg School of Management.

Kelly and I were discussing one of the eternal mysteries in my field—namely, the poor return from American company’s $10 billion investment in training programs to boost employee engagement.

Part of the problem, my daughter patiently explained, is that despite the massive spending on training, companies may end up doing things that stifle rather than promote engagement. It starts with how companies ask questions about employee engagement. The standard practice in almost all organizational surveys on the subject is to rely on what Kelly calls passive questions—questions that describe a static condition. “Do you have clear goals?” is an example of a passive question. It’s passive because it can cause people to think of what is being done to them rather than what they are doing for themselves.

When people are asked passive questions they almost invariably provide “environmental” answers. Thus, if an employee answers “no” when asked, “Do you have clear goals?” the reasons are attributed to external factors such as “My manager can’t make up his mind” or “The company changes strategy every month.” The employee seldom looks within to take responsibility and say, “It’s my fault.” Blame is assigned elsewhere. The passive construction of “Do you have clear goals?” begets a passive explanation (“My manager doesn’t set clear goals”).

The result, argued Kelly, is that when companies take the natural next step and ask for positive suggestions about making changes, the employees’ answers once again focus exclusively on the environment, not the individual. “Managers need to be trained in goal setting” or “Our executives need to be more effective in communicating our vision” are typical responses. The company is essentially asking, “What are we doing wrong?”—and the employees are more than willing to oblige with a laundry list of the company’s mistakes.

There is nothing inherently evil or bad about passive questions. They can be a very useful tool for helping companies know what they can do to improve. On the other hand, they can produce a very negative unintended consequence. When asked exclusively, passive questions can be the natural enemy of taking personal responsibility and demonstrating accountability. They can give people the unearned permission to pass the buck to anyone and anything but themselves.

Active questions are the alternative to passive questions. There’s a difference between “Do you have clear goals?” and “Did you do your best to set clear goals for yourself?” The former is trying to determine the employee’s state of mind; the latter challenges the employee to describe or defend a course of action. Kelly was pointing out that passive questions were almost always being asked while active questions were being ignored.

In my experience, fully engaged employees are positive and proactive about their relationship to the job. They not only feel good about what they’re doing; they don’t mind showing off their enthusiasm to the world. Using those qualities—positive versus negative, proactive versus passive—I tracked the responses to my 11 million miles card to distinguish four levels of engagement:

Committed: The proactively positive employees would examine the card as if they’d never seen it before, and say some variation on “Hey, this is cool.” Some would call over another employee to check out the card. They’d all thank me for my loyalty—and they meant it. Even though we were in the middle of a quickly forgotten exchange—it didn’t rise to the level of a transaction, certainly not a relationship—and would not see each other again, the employees made me feel great. That’s engagement.

Professional: Then there are the passively positive responses, best expressed by the woman behind the desk in Dallas who offered the sincere pleasantry, “We appreciate your loyalty, sir.” That’s okay. She made me feel appreciated. She was being a professional.

Cynical: The most common response I get is the passively negative tone of “That’s nice, sir.” Or “That’s interesting.” Bored with their job and indifferent to customers, these employees opt for the passive-aggressiveness of being superficially engaged with what they’re doing but conveying through their tone of voice that they really don’t care.

Hostile: At the bottom of the engagement barrel are the proactively negative types who dislike their jobs and can barely tolerate me. At their best, they treat me as an object of sympathy (“I hope that you don’t have to keep doing this much longer”). At their worst they attack me for simply existing, as in the man who took my card and said, “I’m really tired of you people who fly all the time and expect to get so much back from the airline because you have miles.” (The way he stretched out “miles” into three syllables was particularly gratifying. As a general rule, when I hear the words “you people” I know nothing nice will follow. And he didn’t disappoint.)

In the first study, we used three different groups. The first group was a control group that received no training and was asked “before and after” questions on happiness, meaning, building positive relationships, and engagement.

The second group went to a two-hour training session about “engaging yourself” at work and home. This training was followed up every day (for ten working days) with passive questions:

- How happy were you today?

- How meaningful was your day?

- How positive were your relationships with people?

- How engaged were you?

The third group went to the same two-hour training session. Their training was followed up every day (for ten working days) with active questions:

- Did you do your best to be happy?

- Did you do your best to find meaning?

- Did you do your best to build positive relationships with people?

- Did you do your best to be fully engaged?

At the end of two weeks, the participants in each of the three groups were asked to rate themselves on increased happiness, meaning, positive relationships, and engagement.

The results were amazingly consistent. The control group showed little change (as control groups are wont to do). The passive questions group reported positive improvement in all four areas. The active questions group doubled that improvement on every item! Active questions were twice as effective at delivering training’s desired benefits to employees. While any follow-up was shown to be superior to no follow-up, a simple tweak in the language of follow-up—focusing on what the individual can control—makes a significant difference.

One study never answers all our questions. To the contrary, it only makes us hungrier for more answers. So we initiated a second ongoing study, this time with the steady stream of participants in my leadership seminars, in which people answered six active questions every day for ten working days. I “reverse-engineered” the questions based on my experience and the literature on the factors that make employees feel engaged. Here are the six Engaging Questions I settled on—and why.

- Did I do my best to set clear goals today?

Employees who have clear goals report greater engagement than employees who don’t. No surprise. If you don’t have clear goals and ask yourself, “Am I fully engaged?” the obvious follow-up is “Engaged to do what?” This is true within big organizations as well as for individuals. No clear goals, no engagement. After the 2008 financial crisis I worked with executives at a bank that had gone through three “revolving door” CEOs in three years. The organization was directionless, and it showed in the disintegrating engagement scores of the senior management. The lowest scores were attached to the question “Do I have clear goals?” Tweaking the question into active form made an immediate difference. Executives demoralized by their leaders’ fecklessness became dramatically more engaged after they started setting their own direction for the day instead of futilely waiting to receive it from someone else. - Did I do my best to make progress toward my goals today?

Teresa Amabile, in her scrupulous research and in The Progress Principle, has shown that employees who have a sense of “making progress” are more engaged than those who don’t. We don’t just need specific targets; we need to see ourselves nearing, not receding from, the target. Anything less is frustrating and dispiriting. Imagine how you’d feel if you chose a goal and instead of getting better at it, you got worse. How engaged would you be? Progress makes any of our accomplishments more meaningful. - Did I do my best to find meaning today?

At this late date, I don’t think we have to strenuously argue that finding meaning and purpose improves our lives. I defer here to Viktor Frankl’s 1946 classic, Man’s Search for Meaning. Frankl, an Auschwitz survivor, describes how the struggle to find meaning—the struggle, not the result—can protect us in even the most unimaginable environments. It’s up to us, not an outside agency like our company, to provide meaning. This question challenges us to be creative in finding meaning in whatever we are doing. - Did I do my best to be happy today?

People still debate if happiness is a factor in employee engagement. I think that because happiness goes hand in hand with meaning, you need both. When employees report that they are happy but their work is not meaningful, they feel empty—as if they’re squandering their lives by merely amusing themselves. On the other hand, when employees regard their work as meaningful but are not happy, they feel like martyrs (and have little desire to stay in such an environment). As Daniel Gilbert shows in Stumbling on Happiness,we are lousy at predicting what will make us happy. We think our source of happiness is “out there” (in our job, in more money, in a better environment) but we usually find it “in here”—when we quit waiting for someone or something else to bring us joy and take responsibility for locating it ourselves. We find happiness where we are. - Did I do my best to build positive relationships today?

The Gallup company asked employees, “Do you have a best friend at work?” and found the answers directly related to engagement. By flipping the question from passive to active, we’re reminded to continue growing our positive relationships, even create new ones, instead of judging our existing relationships. One of the best ways to “have a best friend” is to “be a best friend.” - Did I do my best to be fully engaged today?

This gets to the head-spinning core of the Engaging Questions: To increase our level of engagement, we must ask ourselves if we’re doing our best to be engaged. A runner is more likely to run faster in a race by running faster when she trains—and timing herself. Likewise, an employee will be more engaged at work if she consciously tries to be more engaged—and rigorously measures her effort. It’s a self-fulfilling dynamic: the act of measuring our engagement elevates our commitment to being engaged—and reminds us that we’re personally responsible for our own engagement.

There are six questions my class attendees voluntarily consider. After ten days we follow up and essentially ask, “How’d you do? Did you improve?” So far we have conducted 79 studies with 2,537 participants. The results have been incredibly positive.

- 37% of participants reported improvement in all six areas.

- 65% improved on at least four items.

- 89% improved on at least one item.

- 11% didn’t change on any items.

- 0.4% got worse on at least one item (go figure!).

Given people’s demonstrable reluctance to change at all, this study shows that active self-questioning can trigger a new way of interacting with our world. Active questions reveal where we are trying and where we are giving up. In doing so, they sharpen our sense of what we can actually change. We gain a sense of control and responsibility instead of victimhood.

When I asked myself, “Did I say or do something nice for Lyda?”, I could call in a few minutes, say “I love you,” and declare victory. When I asked myself, “Did I do my best to be a good husband?”, I learned that I had set the bar much higher for myself.

This “active” process will help anyone get better at almost anything. It only takes a couple of minutes a day. But be warned: it is tough to face the reality of our own behavior—and our own level of effort—every day.

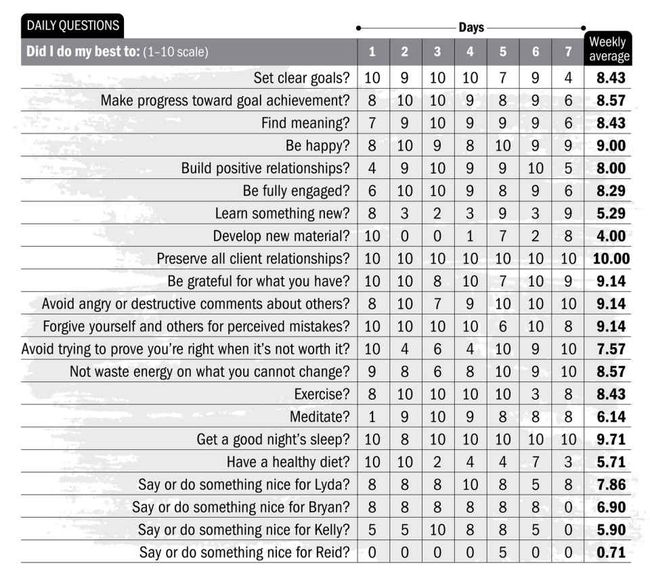

Since then I’ve gone through many permutations of my Daily Questions. The list isn’t working if it isn’t changing along the way—if I’m not getting better on some issues and adding new ones to tackle. Here’s my current list of twenty-two “Did I do my best?” questions that I review every day:

As you can see, my first six questions are the Engaging Questions that I suggest for everyone. My next eight questions revolve around cornerstone concepts in The Wheel of Change, where I’m either creating, preserving, eliminating, or accepting. For example, learning something new or producing new editorial content is creating. Expressing gratitude is preserving. Avoiding angry comments is eliminating, and so is avoiding proving I’m right when it’s not worth it. Making peace with what I cannot change and forgiving myself is accepting. And the remaining questions are about my family and my health.

There’s no correct number of questions. The number is a personal choice, a function of how many issues you want to work on. Some of my clients have only three or four questions to go through each night. My list is twenty-two questions deep because I need a lot of help (obviously) but also because I’ve been doing this a long time. I’ve had years to deal with some of the broad interpersonal issues that seem like obvious targets for successful people just starting out with Daily Questions—for example, suppressing the need to win at all times or being more collaborative. I’ve “conquered” these issues, at least to the point that they’re no longer overriding issues worthy of my Daily Questions list.

The week I’m covering in the spreadsheet above is typical for me outside the United States. I traveled from New York to Rome, then Barcelona, then Madrid, then Zurich, and ended with boarding a flight to Djakarta via Singapore. I gave lengthy presentations in each of the three European cities. I had some travel frustrations—a driver who didn’t show up (which I could have used as an excuse to get angry). I had some good nights of sleep and some not-so-good (which I could have blamed on the changing time zones in my schedule). I had challenges with my diet, since Rome and Madrid have tempting dining scenes (which I could have used as an excuse to eat too much). I totally enjoyed the time I was standing up in front of people and making a presentation. I spent a lot of time on emails and minor distractions. I didn’t get as much writing done as I hoped. All of these outcomes are there for me to reflect on each night as I put in my scores. The net reflection on this particular week: I need to be a better father-in-law. (My son-in-law Reid is a great guy.) My schedule is a little crazy for a sixty-five-year-old man. I want to continue doing what I’m doing, but maybe slow down a bit. (We’ll see. If I don’t add this goal to my Daily Questions, I probably don’t mean it.)

The point is, your Daily Questions should reflect your objectives. They’re not meant to be shared in public (unless you’re writing a book on the subject), meaning they’re not designed to be judged. You’re not constructing your list to impress anyone. It’s your list, your life. I score my “Did I do my best” questions on a simple 1 to 10 scale. You can use whatever works for you. Your only considerations should be:

- Are these items important in my life?

- Will success on these items help me become the person that I want to be?

Active questions are not a distinction without a difference. Professional pollsters have always known that how questions are posed to interview subjects significantly influences the polling results. (For example, there’s a difference between asking if I agree or disagree with the statement, “The best way to ensure peace is through military strength” and asking me to choose between “The best way to ensure peace is through military strength” and “Diplomacy is the best way to ensure peace.” The military option is far less popular when people are also given the diplomacy option.)

This is the most astonishing benefit: eventually we become the Coach. I know this is true because of all my clients who got better—and continued improving without me.

Every endeavor comes with a first principle that dramatically improves our chances of success at that endeavor.

- In carpentry it’s Measure twice, cut once.

- In sailing it’s Know where the wind is coming from.

- In women’s fashion it’s Buy a little black dress.

I have a first principle for becoming the person you want to be. Follow it and it will shrink your daily volume of stress, conflict, unpleasant debate, and wasted time. It is phrased in the form of a question you should be asking yourself whenever you must choose to either engage or “let it go.”

Am I willing,

at this time,

to make the investment required

to make a positive difference

on this topic?

It’s a question that pops into my head so often each day that I’ve turned the first five words into an acronym, AIWATT (it rhymes with “say what”). Like the physician’s principle, First, do no harm, it doesn’t require you to do anything, merely avoid doing something foolish.

The question is a mash-up of two bits of guidance I’ve valued over the years, one part Buddhist insight, the other part common sense from the late Peter Drucker.

The Buddhist wisdom is contained in the Parable of the Empty Boat:

A young farmer was covered with sweat as he paddled his boat up the river. He was going upstream to deliver his produce to the village. It was a hot day, and he wanted to make his delivery and get home before dark. As he looked ahead, he spied another vessel, heading rapidly downstream toward his boat. He rowed furiously to get out of the way, but it didn’t seem to help.

He shouted, “Change direction! You are going to hit me!” To no avail. The vessel hit his boat with a violent thud. He cried out, “You idiot! How could you manage to hit my boat in the middle of this wide river?” As he glared into the boat, seeking out the individual responsible for the accident, he realized no one was there. He had been screaming at an empty boat that had broken free of its moorings and was floating downstream with the current.

We behave one way when we believe that there is another person at the helm. We can blame that stupid, uncaring person for our misfortune. This blaming permits us to get angry, act out, assign blame, and play the victim.

单词列表:

| words | sentence |

|---|---|

| unparalleled | we have greatly benefited from his unparalleled experience and his knowledge |

| illuminating | he shares illuminating stories from his work with great global leaders |

| holistic | He helps us transform our lives and become more holistic human beings |

| aspire | for those who aspire to leadership |

| intention | a hands-on framework for helping people live with intention and greater purpose |

| embark | In order to become the person we aspire to be, we need to embark on a journey of awareness that requires attention, action, and discipline. |

| extract | His coaching techniques and valuable lessons empower you to extract greater meaning from interpersonal relationships |

| relentlessly | Marshall’s coaching invites leaders to focus relentlessly on their behavior |

| rigor | He has taught me, as he has countless others, how to bring rigor and compassion to being a leader. |

| blend | He has a unique blend of intelligence, insight, and practical steps to improve performance |

| nudge | I have come away with valuable insights which will help nudge me toward becoming the person I want to be |

| candid | Triggers is the most straightforward, clear, candid, no-fads, practical advice you’ll ever get on how to make change happen in your life |

| compelling | shares profound insights, compelling stories, and powerful techniques that you can put to use now that will benefit your career |

| raving | I’m a raving fan of Marshall Goldsmith |

| Packed with | Packed with awesome real truths about how we are with ourselves and how to make life better |

| distills | Marshall Goldsmith distills wisdom gained from decades of helping people |

| engaging | the book is written in an engaging, approachable way |

| approachable | the book is written in an engaging, approachable way |

| provocateur | Marshall is more than just a coach. He’s a provocateur, a humorist, and a challenger |

| humorist | Marshall is more than just a coach. He’s a provocateur, a humorist, and a challenger |

| flameout | There are things about myself that I want to change or improve but I always flameout after a little while |

| consistency | allows us to overcome the main roadblocks to positive change: consistency and the environment |

| delightful | A wise book with delightful stories on how to self-actualize |

| self-actualize | A wise book with delightful stories on how to self-actualize |

| quirks | he is also one of the world’s top observers of smart, driven people and their many behavioral quirks |

| tics | you’ll recognize your own tics in many of Marshall’s telling anecdotes |

| anecdotes | you’ll recognize your own tics in many of Marshall’s telling anecdotes |

| pragmatic | as well as a pragmatic blueprint for self-renewal, restoration, and realization |

| restoration | as well as a pragmatic blueprint for self-renewal, restoration, and realization |

| realization | as well as a pragmatic blueprint for self-renewal, restoration, and realization |

| roller coaster | Get ready for a roller coaster ride on the most important adventure of your life |

| sustainable | They have ‘done their best’ to prepare insightful, useful, and practical tips to ensure sustainable behavioral change |

| knee-to-knee | Reading this book feels like having Marshall ‘knee-to-knee’ coaching me |

| savor | What a privilege it is to learn from his insights, savor his stories, and fully engage in positive personal change |

| impacted | fifty great leaders who have impacted the field of management over the past eighty years |

| leaning | I saw a beggar leaning on his wooden crutch |

| crutch | I saw a beggar leaning on his wooden crutch |

| tripped down | My colleague Phil tripped down his basement steps and landed hard on his head |

| tingling | For a few moments as he lay on the floor, his arms and shoulders tingling, he thought he was paralyzed |

| paralyzed | For a few moments as he lay on the floor, his arms and shoulders tingling, he thought he was paralyzed |

| wobbly | Too wobbly to stand up, he sat against a wall and assessed the damage |

| throbbing | His head and neck were throbbing |

| trickling | He could feel blood trickling down his back from a lacerated scalp |

| lacerated | He could feel blood trickling down his back from a lacerated scalp |

| scalp | He could feel blood trickling down his back from a lacerated scalp |

| ER | He knew that he needed to go to an ER so they could clean up the wound and check for broken bones and internal bleeding |

| no shape to | He also knew he was in no shape to drive himself |

| grown | Phil’s wife and grown sons were not home |

| suburban | He was alone in his quiet suburban house |

| scrolled | As he scrolled through names he realized he didn’t have a single friend nearby whom he felt comfortable calling in an emergency |

| gushing | reluctant to call 911 since he wasn’t gushing blood or having a heart attack |

| rushed over | He explained his situation and Kay rushed over, entering Phil’s home through an unlocked back door |

| concussion | Yes, he’d suffered a concussion, the doctors said, and he’d be in pain for a few weeks |

| brittle | the bright brittle sound at impact, like a hammer coming down on a marble counter and shattering the stone into tiny pieces |

| marble | the bright brittle sound at impact, like a hammer coming down on a marble counter and shattering the stone into tiny pieces |

| counter | the bright brittle sound at impact, like a hammer coming down on a marble counter and shattering the stone into tiny pieces |

| electrical charge | He remembered the electrical charge coursing through his limbs |

| limbs | He remembered the electrical charge coursing through his limbs |

| gratitude | But Phil’s fall triggered more than gratitude for not being crippled |

| crippled | But Phil’s fall triggered more than gratitude for not being crippled |

| selflessly | she had selflessly given up her day for him |

| omnipresent | omnipresent challenge any successful person must stare down |

| smattering | nearly all successes but a smattering of failures, too |

| rattled | This development rattled the CEO |

| loathed | Who could say how many opportunities had vanished because people loathed being pummeled and browbeaten |

| pummeled | Who could say how many opportunities had vanished because people loathed being pummeled and browbeaten |

| browbeaten | Who could say how many opportunities had vanished because people loathed being pummeled and browbeaten |

| marijuana | illegally selling supersize soft drinks was double the fine for selling marijuana |

| willpower | I have willpower and won’t give in to temptation |

| Odysseus | the hero Odysseus faces many perils and tests on his return home from the Trojan War |

| Trojan War | the hero Odysseus faces many perils and tests on his return home from the Trojan War |

| epiphany | An epiphany will suddenly change my life |

| maître | making nasty comments to the maître d’—neither of whom cooked the food |

| Louis XIV | it’s not because we regularly display the noblesse oblige of Louis XIV |

| the control group | The control group showed little change |

| pro bono | When we’re working pro bono |