作者 简单的镜子

转载请标明原作者和出处

也可以关注我的

TIME’S ARROW IS BENT INTO A LOOP

Memory was one of the first fields of study for psychologists in the 19th century, as it was closely connected with the concept of consciousness, which had formed the bridge between philosophy and psychology. Hermann Ebbinghaus in particular devoted much of his research to the scientific study of memory and learning, but the next generation of psychologists turned their attention to a behaviourist study of learning, and “conditioning” replaced memory as the focus of research.

Apart from a few isolated studies, notably by Bluma Zeigarnik and Frederic Bartlett in the 1920s and 30s, memory was largely ignored as a topic until the “cognitive revolution” took place following World War II. Cognitive psychologists began to explore the idea of the brain as an information processor, and this provided a model for the storage of memory: it was seen as a process, whereby some items passed from short-term or working memory into long-term memory.

By the time Endel Tulving finished his doctorate in 1957, memory was once more a central area of study. Forced to abandon the study of visual perception due to a lack of facilities, Tulving turned his attention to memory. The funding deficit also shaped his approach to the subject, designing experiments that used no more than a pen, some paper, and a supply of index cards.

"Relating what we know about the behaviour of memory to the underlying neural structures is not at all obvious. That’s real science."

Endel Tulving

The free-recall method

Learning about the subject as he went along, Tulving worked in a rather unorthodox way, which occasionally earned him criticism from his peers, and was to make publishing his results difficult. His maverick instincts did, however, lead to some truly innovative research. One hurriedly designed, ad hoc demonstration to a class of students in the early 1960s was to provide him with the model for many later experiments.

He read out a random list of 20 everyday words to the students, and then asked them to write down as many as they could recall, in any order. As he expected, most of them managed to remember around half of the list. He then asked them about the words that they had not remembered, giving hints such as “Wasn’t there a colour on the list?”, after which the student could often provide the correct answer.

Tulving developed a series of experiments on this “free recall” method, during which he noticed that people tend to group words together into meaningful categories; the better they organize the information, the better they are able to remember it. His subjects were also able to recall a word when given a cue in the form of the category (such as “animals”) in which they had mentally filed that word.

Tulving concluded that although all the words memorized from the list were actually available for remembering, the ones that were organized by subject were more readily accessible to memory, especially when the appropriate cue was given. In Tulving’s free recall experiments, people were asked to remember as many words as possible from a random list. “Forgotten” words were often recalled using category cues. They were stored in memory but temporarily inaccessible.

Memory types

Where previous psychologists had concentrated on the process of storing information, and the failings of that process, Tulving made a distinction between two different processes – storage and retrieval of information – and showed how the two were linked.In the course of his research, Tulving was struck by the fact that there seemed to be different kinds of memory.

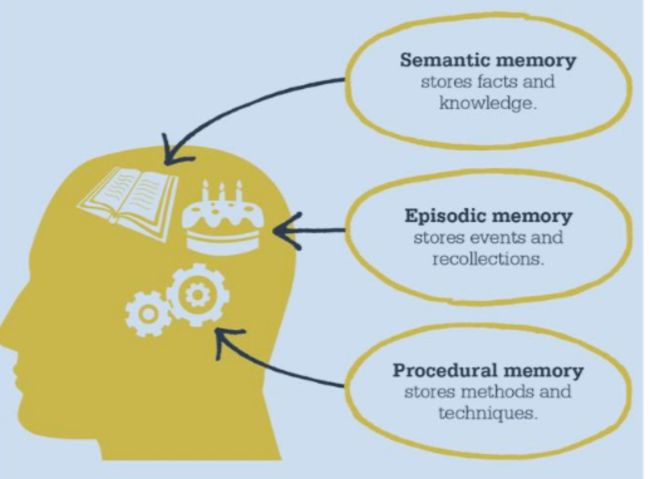

The distinction between long-term memory and short-term memory had already been established, but Tulving felt there was more than one kind of long-term memory. He saw a difference between memories that are knowledge-based (facts and data), and those that are experience-based (events and conversations).

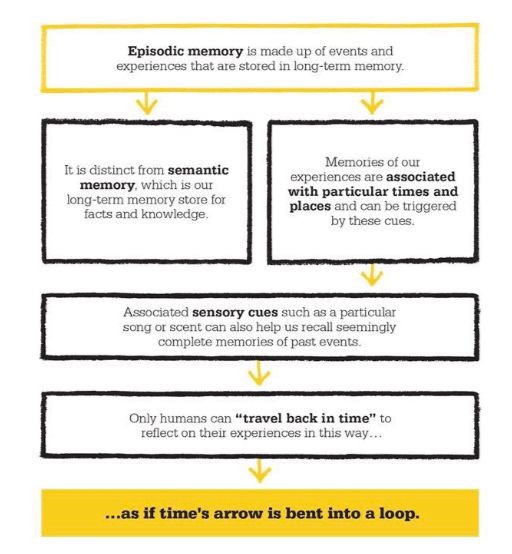

He proposed a division of long-term memory into two distinct types: semantic memory, the store of facts; and episodic memory, the repository of our personal history and events. Tulving’s experiments had demonstrated that organization of semantic information, such as lists of words, helps efficient recollection, and the same appeared to be true of episodic memory. But where semantic memories are organized into meaningful categories of subject matter, episodic memories are organized by relation to the specific time or circumstances in which they were originally stored.

For example, a particular conversation may have taken place during a birthday dinner, and the memory of what was said would be stored in association with that occasion. Just as the category of “city” might provide a retrieval cue for the semantic memory “Beijing”, the mention of “40th birthday” might act as a cue for the retrieval of what had been said over that dinner. The more strongly these autobiographical memories are associated with the time and circumstances of their occurrence, the greater their accessibility is likely to be.

“Flashbulb memories”, which are stored when a highly memorable event – such as the 9/11 terrorist attacks – occurs, are an extreme example of this. Tulving described recollection from episodic memory as “mental time travel”, involving us in a revisiting of the past to access the memory. In his later work he pointed out that episodic memory is unique in featuring a subjective sense of time.

Specific to humans, it involves not merely awareness of what has been, but also of what may come about. This unique ability allows us to reflect on our lives, worry about future events, and make plans. It is what enables humankind to “take full advantage of its awareness of its continued existence in time” and has allowed us to transform the natural world into one of numerous civilizations and cultures. Through this facility, “time’s arrow is bent into a loop”.

"Remembering is mental time travel."

Endel Tulving

Encoding information

Tulving realized that organization is the key to efficient recall for both semantic and episodic memory, and that the brain somehow organizes information so that specific facts and events are “pigeonholed ” with related items. Recalling that specific information is then made easier by direction to the appropriate pigeonhole – the brain “knows where to look” for the memory it wants and can narrow down the search.

The implication, he believed, is that the brain encodes each memory for storage in long-term memory, so that specific memories can be located for recollection by a more general retrieval cue. The cues that prompt episodic memory are usually sensory. A specific sound, such as a piece of music, or a scent can trigger a complete memory. Tulvings’s theory of the “encoding specificity principle” was especially applicable to episodic memory.

Memories of specific past events are encoded according to the time of their occurrence, along with other memories of the same time. He found that the most effective cue for retrieving any specific episodic memory is the one which overlaps with it most, as this is stored together with the memory to be retrieved. Retrieval cues are necessary to access episodic memory, but not always sufficient, because sometimes the relationship is not close enough to allow recollection, even though the information is stored and available in long-term memory.

Unlike previous theories of memory, Tulving’s encoding principle made a distinction between memory that is available and that which is accessible. When someone is unable to recall a piece of information, it does not mean that it is “forgotten” in the sense that it has faded or simply disappeared from long-term memory; it may still be stored, and therefore be available – the problem is one of retrieval.

Different types of memory are physically distinct, according to Tulving, because each behaves and functions in a significantly different way.

Scanning for memory

Tulving’s research into the storage and retrieval of memory opened up a whole new area for psychological study. The publication of his findings in the 1970s coincided with a new determination by many cognitive psychologists to find confirmation of their theories in neuroscience, using brain-imaging techniques that had just become available.

In conjunction with neuroscientists, Tulving was able to map the areas of the brain that are active during encoding and retrieval of memory, and establish that episodic memory is associated with the medial temporal lobe and, specifically, the hippocampus Partly due to his unorthodox and untutored-approach, Tulving made innovative insights that proved inspirational to other psychologists, including some of his former students such as Daniel Schacter.

Tulving’s focus on storage and retrieval provided a new way of thinking about memory, but it was perhaps his distinction between semantic and episodic memory that was his breakthrough contribution. It allowed subsequent psychologists to increase the complexity of the model to include such concepts as procedural memory (remembering how to do something), and the difference between explicit memory (of which we are consciously aware) and implicit memory (of which we have no conscious awareness, but which nonetheless continues to affect us).

These topics remain of great interest to cognitive psychologists today. Emotional events such as weddings give rise to episodic memories. These are stored in such a way that the person remembering relives the event, in a form of “time travel”.

MORE TO KNOW…

APPROACH

Memory studies

BEFORE

1878 Hermann Ebbinghaus conducts the first scientific study of human memory.

1927 Bluma Zeigarnik describes how interrupted tasks are better remembered than uninterrupted ones.

1960s Jerome Bruner stresses the importance of organization and categorization in the learning process.

AFTER

1979 Elizabeth Loftus looks at distortions of memory in her book Eyewitness Testimony.

1981 Gordon H. Bower makes the link between events and emotions in memory.

2001 Daniel Schacter publishes The Seven Sins of Memory: How the Mind Forgets and Remembers.

ENDEL TULVING

Born the son of a judge in Tartu, Estonia, Endel Tulving was educated at a private school for boys, and although a model student, he was more interested in sports than academic subjects. When Russia invaded in 1944, he and his brother escaped to Germany to finish their studies and did not see their parents again until after the death of Stalin 9 years later. After World War II, Tulving worked as a translator for the American army and briefly attended medical school before emigrating to Canada in 1949.

He was accepted as a student at the University of Toronto, where he graduated in psychology in 1953, and took his MA degree in 1954. He then moved to Harvard where he gained a PhD for his thesis on visual perception. In 1956, Tulving returned to the University of Toronto, where he continues to teach to this day.

Key works

1972 Organization of Memory

1983 Elements of Episodic Memory

1999 Memory, Consciousness, and the Brain

以下是我写的关于The Psychology Book的其他章节,欢迎各位前来观看 ^ ^