前言:本文来自知名科技博主Ben Thompson的在2016年2月的一次分享,文章距现在已经有一段时间了,但从原理和应用性角度从发,依旧非常有借鉴价值.今天也是圣诞假期,值此机会,祝愿Alpha Society的每一位朋友,圣诞快乐!

Merry Christmas!

Enjoy!

本文转载自stratechery.com

THE REALITY OF MISSING OUT

BY BEN THOMPSON

When it comes to ad-supported services, pundits everywhere are fond of the adage “If you’re not the customer you’re the product”. It’s interesting, though, how quickly that adage is forgotten when it comes to evaluating the viability of said services.

Twitter is a perfect example. In response to my pieceHow Facebook Squashed TwitterI got a whole host of responses along the lines of this fromJohn Gruber:

I have argued for years that the fundamental problem is that Twitter is compared to Facebook, and it shouldn’t be. Facebook appeals to billions of people. “Most people”, it’s fair to say. Twitter appeals to hundreds of millions of people. That’s amazing, and there’s tremendous value in that — but it’s no Facebook. Cramming extra features into Twitter will never make it as popular as Facebook — it will only dilute what it is that makes Twitter as popular and useful as it is.

From a user’s perspective, I completely agree. But remember the adage: it’s the customers that matter, and from an advertiser’s perspective Facebook and Twitter are absolutely comparable, which is the root of the problem for the latter. Digital advertising is becoming a rather simple proposition: Facebook, Google, or don’t bother.

CONSUMER SERVICE CARNAGE

Last Friday LinkedIn suffered one of the worst days the stock market has ever seen, plummeting 40% despite the fact the companybeatexpectations for both revenue and adjusted earnings; the slide was prompted by significantly lower guidance than investors expected.

The issue for LinkedIn is that a company’s stock price is not a scorecard;

rather it is the market’s estimate of a company’sfutureearnings, and the ratio to which the stock price varies from current earnings is the degree to which investors expect said earnings to grow. In the case of LinkedIn, the company’s relatively mature core business serving recruiters continues to do well; that’s why the company beat estimates. That market, though, has a natural limit, which means growth must be found elsewhere, and LinkedIn hoped that elsewhere would be in advertising. The lower-than-expected estimates and shuttering of Lead Accelerator, LinkedIn’s off-site advertising program (which follows on the heels of LinkedIn’s previous decision to end display advertising), suggested that said growth may not materialize.

Yelp, meanwhile, was only down 11% yesterday after releasing earnings (and issuing guidance) that weren’t that terrible.

The company’s big hit came last summer when the stock plummeted 28% in a single day on, you guessed it, a lower-than-expected forecast, based in part on Yelp’s decision to end its brand advertising program.

Yahoo’s core business, meanwhile, is practically worthless as revenues and earnings continue to decline, and the aforementioned Twitter has seen its valuation slump below $10 billion; both are in stark contrast to the companies each has traditionally been associated with: Google is worth $460 billion (and was briefly the most valuable company in the world) and Facebook is worth $267 billion.

The reason for such a stark bifurcation is, ultimately, all about the “customer”: the advertiser actually buying the ads that underlie all of these “free” consumer services.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF ANALOG ADVERTISING

Newspapers are the oldest tool in the advertiser’s chest, and were for many years the only one. This wasn’t a problem because newspapers had the magical ability to expand or contract based on how much advertising was sold for a particular day; from a business perspective, editorial has always been filler.

For the first half of the 20th century, U.S. aggregate newspaper revenue growth roughly tracked GDP, which is what you would expect given thatadvertising has always beenaround 1.2% of economic activity for as long as such things have been tracked. In the second half of the century, though, the rate of growth for newspapers slowed just a bit, thanks to the advent of first radio and then television.

Both radio and television advertising had distinct advantages relative to newspaper advertising, both in terms of storytelling and especially their effectiveness in capturing potential consumers’ attention. Still, while newspapers were no longer capturing all of the advertising dollars, they still grew nicely because both radio and television had three important limitations:

Because both radio and television were programmed temporally, there was limited advertising inventory; thus, as you would expect in any situation where supply is scarce, prices were significantly higher

It was much more expensive to produce an effective radio or television advertising slot relative to a newspaper ad

It was difficult to measure the return-on-investment of radio and television advertising; newspapers weren’t that much better, although things like coupons could be tracked more closely

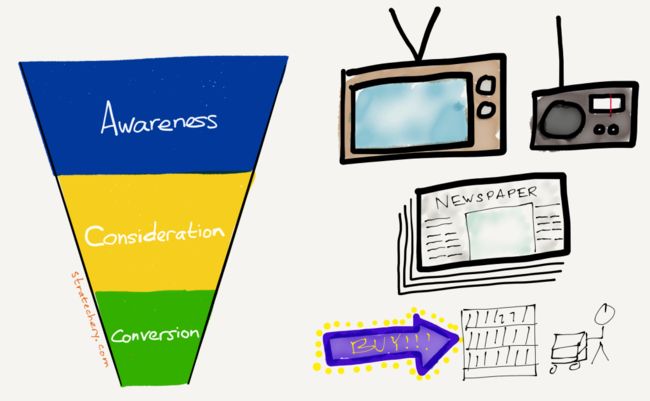

Ultimately, advertisers (known as “brand managers” in the consumer-packaged goods industry, which pioneered these techniques) developed strategies that leveraged all three mediums, plus on-the-spot promotions at retailers, to move customers “down the funnel”:

TV and radio were particularly effective at building awareness — making customers aware that your product existed — and also at building brand affinity — the subconscious preference for your product over a competing product at the moment of purchase. Newspapers, meanwhile, were useful when it came to “consideration”: helping consumers decide to buy the product they were now aware of (coupons were very useful here). Finally, brand managers spent a lot of time and money on their relationships with retailers to help pull consumers through the funnel to conversion, with the vague hope that said consumers would prove to be loyal.

DIGITAL ADVERTISING 1.0

The first wave of digital advertising took square aim at the bottom of the funnel: the fact that computers log everything made it easy to demonstrate when an advertisement led directly to a purchase (or a click), and no company benefitted more than Google. Search ads were so effective because consumers were entering the purchase funnel already at the bottom: they already wanted insurance, or to travel, or a lawyer, so Google could charge a lot of money for the right to put an ad for precisely those services right in front of a guaranteed lead and collect every time said lead clicked.

Efforts to implement digital advertising further up the funnel were more mixed; retargeting ads that displayed items you looked at previously were the most blunt and probably most effective attempt to move customers through the consideration phase, even though said bluntness creeped a lot of people out. The top of the funnel, though, never really took off: it really wasn’t clear how to build awareness in a cost effective way on digital.

There were two big problems with brand advertising on the Internet: first, there simply weren’t any good ad units. Banner ads were pale imitations of print ads, which themselves were inferior to more immersive media like radio and especially TV. Secondly, given the more speculative nature of brand advertising, it was much more cost effective to spread your bets over the maximum number of customers; in other words, it remained a better idea to spend your money on an immersive TV commercial that could be broadly targeted based on programming to a whole bunch of potential consumers at a single moment as opposed to spending much more time — which is money! — creating a whole bunch of banner ads that could be more finely targeted.

Today, though, that is beginning to change.

DIGITAL ADVERTISING 2.0

Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg relayed a fascinating anecdote on Facebook’smost recent earnings call:

Leading up to Black Friday, Shop Direct, the UK’s second largest online retailer teased upcoming sales with a cinemagraph video to build awareness. They then retargeted people who saw the video with one day only deals. On Black Friday, they used our carousel and DPA ads to promote products people had shown interest in. They saw 20 times return on ad spend from this campaign, helping them achieve their biggest Black Friday and their most successful sales day ever.

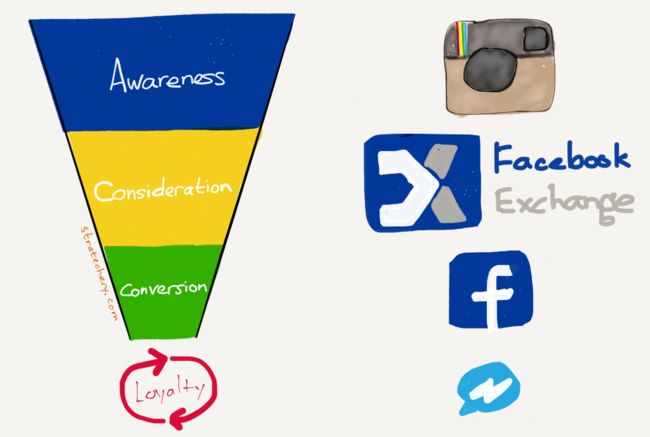

What Sandberg is detailing here is really quite extraordinary: Facebook helped Shop Direct move customers through every part of the funnel: from awareness through Instagram video ads to consideration through retargeting and finally to conversion with dynamic product ads on Facebook (and, in the not too distant future, a direct customer relationship to build loyalty via Messenger).

Google is promising something similar: awareness via properties like YouTube, consideration via DoubleClick, and conversion via AdSense.

Just as importantly, both companies are promising that leveraging their respective platforms will provide benefits on both sides of the ROI equation: the return will be better given the two companies superior targeting capabilities and ability to measure conversion, and the investment will be smaller because you can manage your entire funnel from a single ad-buying interface.

Here’s the kicker, though, and the big difference from the era of analog advertising: the Facebook and Google platforms turn TV and radio’s disadvantages on their head:

Facebook and Google have the most inventory and are still growing in terms of both users and ad-load; there is no temporal limitation that works to the benefit of other properties (and Facebook in particular is ramping up efforts to advertise using Facebook data on non-Facebook properties)

It is cheaper to produce ads for only Facebook and Google instead of making something custom for every potential advertising platform

Facebook and Google have the best tracking, extending not only to digital purchases but increasingly to off-line purchases as well

Both companies, particularly Facebook, havedominantstrategic positions; they are superior to other digital platformson every single vector: effectiveness, reach, and ROI. Small wonder that the smaller players I listed above — LinkedIn, Yelp, Yahoo, Twitter — are all struggling.

THE IMPLICATIONS OF WINNER-TAKES-ALL

I have been arguing for a while thatin the aggregatethe tech sector is fine, and the state of advertising-based services is a perfect example of what I mean: taken as a basket the six companies in this article (Google, Facebook, Yahoo, Twitter, LinkedIn, and Yelp) are up 19% over the last year, even though the latter four companies are down a collective 53%; the fact that Google and Facebook are up a combined 31% more than makes up for it.

This makes sense: while advertising as a whole is a zero-sum game, there is a secular shift from not just print but also radio and TV to digital, which is why this basket of digital advertising companies is up. Digital, though, is subject to the effects ofAggregation Theory, a key component of which is winner-take-all dynamics, and Facebook and Google are indeed taking it all.

I expect this trend to accelerate: first, in digital advertising, it is exceptionally difficult to see anyone outside of Facebook and Google achieving meaningful growth (the potential exceptions being Verizon, which is smartly considering a purchase of Yahoo for reasons I explainedwhen they bought AOL, and especially Snapchat, whichjust signed a deal with Viacomthat is very much inline with my analysis of the company inOld-Fashioned Snapchat; the former has scale, and the latter a hold on the powerful teen demographic).

Everyone else will have an uphill battle to show why they are worth advertisers’ time.

More broadly, the winner-take-all dynamics described by Aggregation Theory have inspired a powerful sense of FOMO (the Fear of Missing Out) amongst investors resulting in a host of unicorns intent on owning their respective industries; I think the recent chill in valuations and fundraising are about coming to terms with the fact that a lot of those unicorns are in the same boat as Facebook and Google’s advertising competitors: they have already missed out to the dominant player in their field (or, that their field was never viable to begin with).

In some respects it is tech’s own inequality story: the average and median company and startup will increasingly bifurcate. It’s not a bubble, it’s a rebalancing, and the winners are poised to be bigger and richer than anything we have seen before.

原文地址:https://stratechery.com/2016/the-reality-of-missing-out/

阿尔法公社,中国领先的天使投资基金

欢迎自荐及推荐优秀早期项目给我们

项目投递绿色通道: [email protected]