2019独角兽企业重金招聘Python工程师标准>>> ![]()

1: Introduction

There is a lot of data that doesn't exist in dataset or API form. A lot of this data is present on the internet, in webpages we interact with. One way to access this data without waiting for the provider to create an API is to use a technique called web scraping.

Web scraping allows us to load a webpage into Python, and extract the information we want. We can then work with the data using normal data analysis tools, like pandas and numpy.

In order to perform web scraping, we need to understand the structure of the webpage that we're working with, then find a way to extract parts of that structure in a sensible way.

As we learn about web scraping, we'll be heavily using the requests library, which enables us to download a webpage, and thebeautifulsoup library, which enables us to extract the relevant parts of a webpage.

2: Webpage Structure

Webpages are coded in HyperText Markup Language (HTML). HTML is not a programming language, like Python, but it is a markup language, and has its own syntax and rules. When a web browser, like Chrome or Firefox, downloads a webpage, it reads the HTML to know how to render the webpage and display it to you.

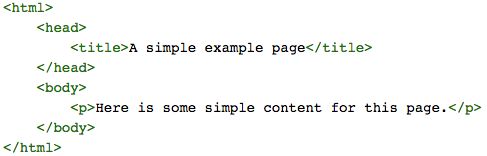

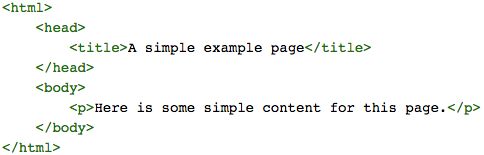

Here is the HTML of a very simple webpage:

You can see this page here. HTML is made up of tags. A tag is opened, like:

![]()

and closed, like:

![]()

Anything in between the opening and closing of a tag is the content of that tag. Tags can be nested to create complex formatting rules. For instance:

![]()

The above HTML will be displayed as a bold paragraph because the b tag, which bolds its contents, is inside the p tag. We would say that the b tag is nested within the p tag.

The composition of an HTML document is broadly split up into the head section, which contains information that is useful to the web browser that is rendering the page, but isn't shown to the user, and the body section, which contains the main information that is shown to the user on the page.

Different tags have different purposes. For example, the title tag tells the web browser what to show as the title of the page in an open tab. The p tag indicates that the content inside is a single paragraph.

We won't dive comprehensively into tags here, but please read this article if you need more of a grounding on HTML. Read this article if you want a list of all possible tags. Understanding the tags and how they work is extremely important to being able to perform web scraping effectively.

Make a GET request to get http://dataquestio.github.io/web-scraping-pages/simple.html.

Instructions

- Make a GET request to get

http://dataquestio.github.io/web-scraping-pages/simple.htmland assign the result to the variableresponse. - Use

response.contentto get the content of the response and assign this tocontent.- Note how the content is the same as the HTML shown above

# Write your code here.

headers={"Authorization": "bearer 13426216-4U1ckno9J5AiK72VRbpEeBaMSKk", "User-Agent": "Dataquest/1.0"}

response=requests.get("http://dataquestio.github.io/web-scraping-pages/simple.html",headers=headers)

content=response.content

content

bytes (

b'\n\n

\nHere is some simple content for this page.

\n \n'response

Response (

headers

dict (

{'Authorization': 'bearer 13426216-4U1ckno9J5AiK72VRbpEeBaMSKk', 'User-Agent': 'Dataquest/1.0'}

3: Retrieving Elements From A Page

Downloading the page is the easy part. Let's say that we want to get the text in the first paragraph. Now we need to parse the page and extract the information that we want.

In order to parse the webpage with python, we'll use the BeautifulSoup library. This library allows us to extract tags from an HTML document.

HTML documents can be thought of as trees due to how tags are nested, and BeautifulSoup works the same way.

For example, looking at this page:

The root of the "tree" is the html tag. Inside the html tag are two "branches", head and body. Inside head is one "branch", title. Inside body is one branch, p. Drilling down through these multiple branches is one way to parse a webpage.

In order to get the text inside the p tag, we would first get the body element, then get the p element, then finally get the text of the p element.

Instructions

- Get the text inside the

titletag and assign the result totitle_text

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

# Initialize the parser, and pass in the content we grabbed earlier.

parser = BeautifulSoup(content, 'html.parser')

# Get the body tag from the document.

# Since we passed in the top level of the document to the parser, we need to pick a branch off of the root.

# With beautifulsoup, we can access branches by simply using tag types as

body = parser.body

# Get the p tag from the body.

p = body.p

# Print the text of the p tag.

# Text is a property that gets the inside text of a tag.

print(p.text)

parser=BeautifulSoup(content,'html.parser')

head=parser.head

title=head.title

title_text=title.text

4: Using Find All

While it's nice to use the tag type as a property, it doesn't always lead to a very robust way to parse a document. Usually, it's better to be more explicit and use the find_all method. find_all will find all occurences of a tag in the current element.

find_all will return a list. If we want only the first occurence of an item, we'll need to index the list to get it. Other than that, it behaves the same way as passing the tag type as an attribute.

Instructions

- Use the

find_allmethod to get the text inside thetitletag and assign the result totitle_text

parser = BeautifulSoup(content, 'html.parser')

# Get a list of all occurences of the body tag in the element.

body = parser.find_all("body")

# Get the paragraph tag

p = body[0].find_all("p")

# Get the text

print(p[0].text)

parser=BeautifulSoup(content,"html.parser")

head=parser.find_all("head")

title=head[0].find_all("title")

print(title[0].text)

5: Element Ids

HTML allows elements to have ids. These ids are unique, and can be used to refer to a specific element.

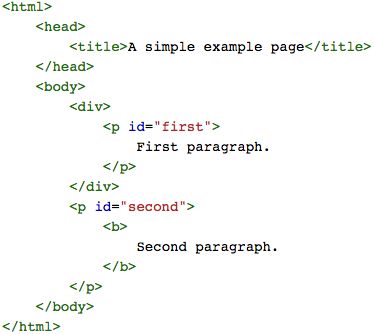

Here's an example page:

You can see the page here.

The div tag is used to indicate a division of the page -- it's used to split up the page into logical units. As you can see, there are two paragraphs on the page, and the first is nested inside a div. Luckily, the paragraphs have been assigned ids -- we can easily access them, even through they're nested.

We can use find_all to do this, but we'll pass in the additional id attribute.

Instructions

- Get the text of the second paragraph (what's inside the second

ptag) and assign the result tosecond_paragraph_text

# Get the page content and setup a new parser.

response = requests.get("http://dataquestio.github.io/web-scraping-pages/simple_ids.html")

content = response.content

parser = BeautifulSoup(content, 'html.parser')

# Pass in the id attribute to only get elements with a certain id.

first_paragraph = parser.find_all("p", id="first")[0]

print(first_paragraph.text)

response=requests.get("http://dataquestio.github.io/web-scraping-pages/simple_ids.html")

content=response.content

parser=BeautifulSoup(content,'html.parser')

second_paragraph=parser.find_all("p",id="second")[0]

second_paragraph_text=second_paragraph.text

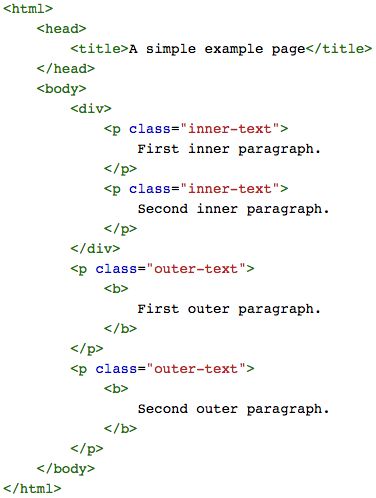

6: Element Classes

HTML also enables elements to have classes. Classes aren't globally unique, and usually indicate that elements are linked. All elements with the same class usually share some kind of characteristic that leads the author of the page to group them into the same class. One element can have multiple classes.

Classes and ids make pages easier to style with CSS, which we'll talk about soon.

You can see the page here.

We can use find_all to select elements by class, we'll just need to pass in the class_ parameter.

Instructions

- Get the text of the second inner paragraph and assign the result to

second_inner_paragraph_text. - Get the text of the first outer paragraph and assign the result to

first_outer_paragraph_tex

# Get the website that contains classes.

response = requests.get("http://dataquestio.github.io/web-scraping-pages/simple_classes.html")

content = response.content

parser = BeautifulSoup(content, 'html.parser')

# Get the first inner paragraph.

# Find all the paragraph tags with the class inner-text.

# Then take the first element in that list.

first_inner_paragraph = parser.find_all("p", class_="inner-text")[0]

print(first_inner_paragraph.text)

second_inner_paragraph=parser.find_all("p",class_="inner-text")[1]

second_inner_paragraph_text=second_inner_paragraph.text

first_outer_paragraph=parser.find_all("p",class_="outer-text")[0]

first_outer_paragraph_text=first_outer_paragraph.text

7: CSS Selectors

Cascading Style Sheets, or CSS, is a way to add style to HTML pages. You may have noticed that our simple HTML pages in the past few screens didn't have any styling -- the paragraphs were all black in color, and the same font size. Most web pages don't only consist of black text. The way that webpages are styled is through CSS. CSS uses selectors that select elements and classes of elements to decide where to add certain stylistic touches, like color and font size changes.

We won't go in depth with CSS here, because that's not our purpose, but if you want to know more, this is a good guide.

What we do need to know is how CSS selectors work.

This CSS will make all text inside all paragraphs red:

p{

color: red

}

You can see an example of this here.

This CSS will make all the text in any paragraphs with the class inner-text red. We select classes with the . symbol:

p.inner-text{

color: red

}

You can see an example of this here.

This CSS will make all the text in any paragraphs with the id first red. We select ids with the # symbol:

p#first{

color: red

}

You can see an example of this here.

You can also style ids and classes without any tags. This css will make any element with the id first red:

#first{

color: red

}

And this will make any element with the class inner-text red:

.inner-text{

color: red

}

What we did in the above examples was use CSS selectors to select one or many elements, and then apply some styling to those elements only. CSS selectors are very powerful and flexible.

Perhaps not surprisingly, CSS selectors are also commonly used in web scraping to select elements.

8: Using CSS Selectors

With BeautifulSoup, we can use CSS selectors very easily. We just use the .select method. Here's the HTML we'll be working with in this screen:

As you can see, the same element can have both an id and a class. We can also assign multiple classes to a single element, we just separate the classes with a space.

You can see this page here.

Instructions

-

Select all the elements with the

outer-textclass.- Assign the text of the first paragraph with the

outer-textclass tofirst_outer_text.

- Assign the text of the first paragraph with the

-

Select all the elements with the

secondid.- Assign the text of the first paragraph with the

secondid to the variablesecond_text

- Assign the text of the first paragraph with the

# Get the website that contains classes and ids

response = requests.get("http://dataquestio.github.io/web-scraping-pages/ids_and_classes.html")

content = response.content

parser = BeautifulSoup(content, 'html.parser')

# Select all the elements with the first-item class

first_items = parser.select(".first-item")

# Print the text of the first paragraph (first element with the first-item class)

print(first_items[0].text)

first_outer_text=parser.select(".outer-text")[0].text

second_text=parser.select("#second")[0].text

9: Nesting CSS Selectors

Just like how HTML has nested tags, we can also nest CSS Selectors to select items that are nested. So we could use CSS selectors to find all of the paragraphs inside the body tag, for instance. Nesting is a very powerful technique that enables us to use CSS to do complex web scraping tasks.

This CSS Selector will select any paragraphs inside a div tag:

div p

This CSS Selector will select any items with the class first-item inside a div tag:

div .first-item

This CSS Selector will select any items with the id first inside a div tag inside a body tag:

body div #first

This CSS Selector will select any items with the id first inside any items with the class first-item:

.first-item #first

As you can see, we can nest CSS selectors in infinite ways. This is how we can extract data from websites with complex layouts. You can easily test selectors by using the .select method as you write them, and it's highly recommended -- it's easy to write a selector that doesn't work how you expect it to.

10: Using Nested CSS Selectors

Now that we know about nested CSS Selectors, let's explore using them. We can use them with the same .select method that we've been using for our CSS Selectors.

We'll be practicing on this HTML:

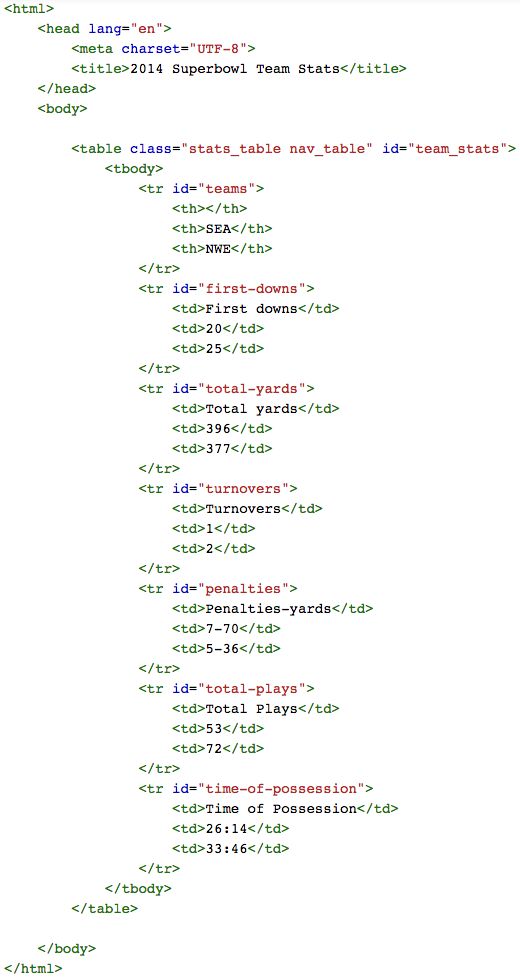

It's an excerpt from a box score of the 2014 Super Bowl, a game played between the New England Patriots and the Seattle Seahawks of theNational Football League. The box score contains information about how many yards each team gained, how many turnovers each team has, and so on. You can see this page here.

The page is rendered to a table, with column and row names. The first column is stats from the Seattle Seahawks, and the second column is stats from the New England Patriots. Each row represents a different statistic.

Instructions

-

Find the Total Plays for the New England Patriots and assign the result to

patriots_total_plays_count. -

Find the Total Yards for the Seahawks and assign the result to

seahawks_total_yards_coun

# Get the super bowl box score data.

response = requests.get("http://dataquestio.github.io/web-scraping-pages/2014_super_bowl.html")

content = response.content

parser = BeautifulSoup(content, 'html.parser')

# Find the number of turnovers committed by the Seahawks.

turnovers = parser.select("#turnovers")[0]

seahawks_turnovers = turnovers.select("td")[1]

seahawks_turnovers_count = seahawks_turnovers.text

print(seahawks_turnovers_count)

patriots_total_plays_count=parser.select("#total-plays")[0].select("td")[2].text

seahawks_total_yards_count=parser.select("#total-yards")[0].select("td")[1].text

11: Beyond The Basics

We've now covered the basics of HTML and how to select elements, which is a key foundational block.

You may be wondering why webscraping is useful, given that in most of our examples, we could easily have found the answer by looking at the page. The real power of webscraping is in being able to get information from a large amount of pages very quickly. Let's say we wanted to find the total yards gained by each NFL team in every single NFL game for a whole season. We could get this manually, but it would take days of boring drudgery. We could write a script to automate this in a couple of hours, and have a lot more fun doing it.