博弈论最小最大算法minmax

转http://www.flyingmachinestudios.com/programming/minimax/

Overview

The minimax algorithm is used to determine which moves a computer player makes in games like tic-tac-toe, checkers, othello, and chess. These kinds of games are called games of perfect information because it is possible to see all possible moves. A game like scrabble is not a game of perfect information because there’s no way to predict your opponent’s moves because you can’t see his hand.

You can think of the algorithm as similar to the human thought process of saying, “OK, if I make this move, then my opponent can only make two moves, and each of those would let me win. So this is the right move to make.”

The rest of the article explains how to represent possible moves and evaluate them. An example command-line tic-tac-toe game using Ruby is given.

Representing Moves with the Game Tree Data Structure

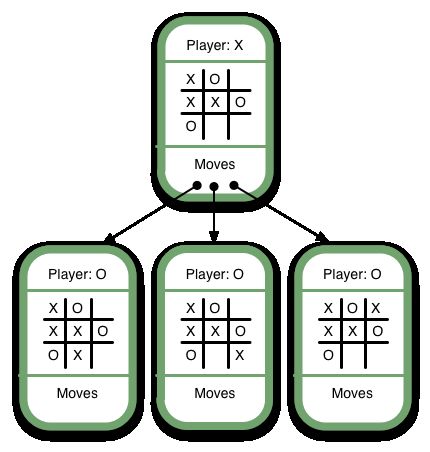

Here’s an example of a Game Tree for tic-tac-toe:

Note that this isn’t a full game tree. A full game tree has hundreds of thousands of game states, so that’s uh… not really possible to include in an image. Some of the discrepancies between the example above and a fully-drawn game tree include:

- The first Game State would show nine moves descending from it, one for each of the empty spaces on its board

- Similarly, the next level of Game States would show eight moves descending from them, and so on for each Game State

Representing the game as a game tree allows the computer to evaluate each of its current possible moves by determining whether it will ultimately result in a win or a loss. We’ll get into how the computer determines this in the next section, Ranking. Before that, though, we need to clearly define the central concepts defining a Game Tree:

- The board state. In this case, where the X’s and O’s are.

- The current player – the player who will be making the next move.

- The next available moves. For humans, a move involves placing a game token. For the computer, it’s a matter of selecting the next game state. As humans, we never say, “I’ve selected the next game state”, but it’s useful to think of it that way in order to understand the minimax algorithm.

- The game state – the grouping of the three previous concepts.

So, a Game Tree is a structure for organizing all possible (legal) game states by the moves which allow you to transition from one game state to the next. This structure is ideal for allowing the computer to evaluate which moves to make because, by traversing the game tree, a computer can easily “foresee” the outcome of a move and thus “decide” whether to take it.

Next we’ll go into detail about how to determine whether a move is good or bad.

Ranking Game States

The basic approach is to assign a numerical value to a move based on whether it will result in a win, draw, or loss. We’ll begin illustrating this concept by showing how it applies to final game states, then show how to apply it to intermediate game states.

Final Game States

Have a look at this Game Tree:

It’s X’s turn, and X has three possible moves, one of which (the middle one) will lead immediately to victory. It’s obvious that an AI should select the winning move. The way we ensure this is to give each move a numerical value based on its board state. Let’s use the following rankings:

- Win: 1

- Draw: 0

- Lose: -1

These rankings are arbitrary. What’s important is that winning corresponds to the highest ranking, losing to the lowest, and a draw’s between the two.

Since the lowest-ranked moves correspond with the worst outcomes and highest-ranked moves correspond with the best outcomes, we should choose the move with the highest value. This is the “max” part of “minimax”. Below are some more examples of final game states and their numerical values:

You might be wondering whether or not we should apply different rankings based on the player whose turn it is. For now, let’s ignore the question entirely and only view things from X’s perspective.

Of course, only the most boring game in the world would start out by presenting you with the options of “win immediately” and “don’t win immediately.” And an algorithm would be useless if it only worked in such a situation. But guess what! Minimax isn’t a useless algorithm. Below I’ll describe how to determine the ranks of intermediate Game States.

Intermediate Game States

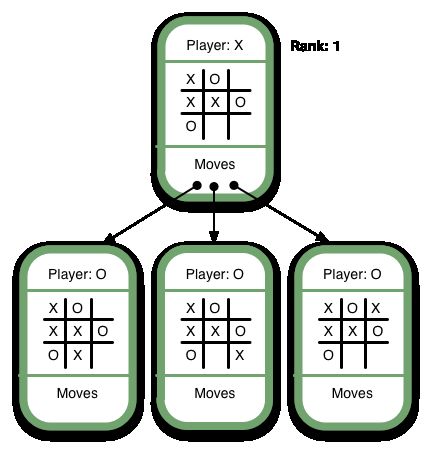

Have another look at this game tree:

As you can see, it’s X’s turn in the top Game State. There are 3 possible moves, including a winning move. Since this Game State allows X to win, X should try to get it if possible. This Game State is as good as winning, so its rank should be 1. In general, we can say that the rank of an intermediate Game State where X is the current player should be set to the maximum rank of the available moves.

Now have a look at this game tree:

It’s O’s turn, and there are 5 possible moves, three of which are shown. One of the moves results in an immediate win for O. From X’s perspective this Game State is equivalent to a loss, since it allows O to select a move that will cause X to lose. Therefore, its rank should be -1. In general, we can say that the rank of an intermediate Game State where O is the current player should be set to the minimum rank of the available moves. That’s what the “mini” in “minimax” refers to.

By the way – the above game tree probably looks ridiculous to you. You might say, “Well of course you shouldn’t make such a dumb move. Why would anyone give up a win and allow O to win?” Minimax is our way of giving the computer the ability to “know” that it’s a dumb move, too.

To sum up:

- Final Game States are ranked according to whether they’re a win, draw, or loss.

- Intermediate Game States are ranked according to whose turn it is and the available moves.

- If it’s X’s turn, set the rank to that of the maximum move available. In other words, if a move will result in a win, X should take it.

- If it’s O’s turn, set the rank to that of the minimum move available. In other words, If a move will result in a loss, X should avoid it.

And that’s the minimax algorithm!

Ruby Example

Below is a Ruby implementation of Tic-Tac-Toe. It has a few limitations – for example, the computer always plays X. This is beacuse it’s meant to illustrate the concepts described here.

To run it, copy it to something like “tictactoe.rb” and run ruby tictactoe.rb.

You can view the repo on github. In the future, I might add Common Lisp and C versions of Tic-Tac-Toe, and I’d welcome versions in other languages as well.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 100 101 102 103 104 105 106 107 108 109 110 111 112 113 114 115 116 117 118 119 120 121 122 123 124 125 126 127 128 129 130 131 132 133 134 135 136 137 138 139 140 141 142 143 144 145 146 147 148 149 150 151 152 153 154 155 156 157 158 159 160 161 162 163 164 165 166 167 168 169 170 171 172 |

|

The End… or Is It???

I hope that explains the algorithm! If anything’s unclear, please let me know in the comments below. I’d like for this post to explain the algorithm completely, and I’ll use any feedback to revise it.

Also, you may have noticed that the algorithm, as written, requires a lot of memory. Tic-Tac-Toe, one of the simplest, most boring games in existence, requires hundreds of thousands of game states in the above, naive Ruby implementation. In the future, I may cover some optimization techniques, like alpha-beta programming. Look for it!

P.S.

My motivation for writing all this came from reading Land of Lisp: Learn to Program in Lisp, One Game at a Time! , which introduced me to minimax. It’s one of the best programming books I’ve read: it was fun to read, and I learned a lot :) It’s also the only programming book I know of to have its own music video.