Think Python - Chapter 11 - Dictionaries

Dictionaries

A dictionary is like a list, but more general. In a list, the indices have to be integers; in a dictionary they can be (almost) any type.

You can think of a dictionary as a mapping between a set of indices (which are called keys) and a set of values. Each key maps to a value. The association of a key and a value is called a key-value pair or sometimes an item.

As an example, we'll build a dictionary that maps from English to Spanish words, so the keys and the values are all strings.

The function dict creates a new dictionary with no items. Because dict is the name of a built-in function, you should avoid using it as a variable name.

>>> eng2sp = dict() >>> print eng2sp {}

The squiggly-brackets, {}, represent an empty dictionary. To add items to the dictionary, you can use square brackets:

>>> eng2sp['one'] = 'uno'

This line creates an item that maps from the key 'one' to the value 'uno'. If we print the dictionary again, we see a key-value pair with a colon between the key and value:

>>> print eng2sp {'one': 'uno'}

This output format is also an input format. For example, you can create a new dictionary with three items:

>>> eng2sp = {'one': 'uno', 'two': 'dos', 'three': 'tres'}

But if you print eng2sp, you might be surprised:

>>> print eng2sp {'one': 'uno', 'three': 'tres', 'two': 'dos'}

The order of the key-value pairs is not the same. In fact, if you type the same example on your computer, you might get a different result. In general, the order of items in a dictionary is unpredictable.

But that's not a problem because the elements of a dictionary are never indexed with integer indices. Instead, you use the keys to look up the corresponding values:

>>> print eng2sp['two'] 'dos'

The key 'two' always maps to the value 'dos' so the order of the items doesn’t matter.

If the key isn’t in the dictionary, you get an exception:

>>> print eng2sp['four'] KeyError: 'four'

The len function works on dictionaries; it returns the number of key-value pairs:

>>> len(eng2sp)

3

The in operator works on dictionaries; it tells you whether something appears as a key in the dictionary (appearing as a value is not good enough).

>>> 'one' in eng2sp True >>> 'uno' in eng2sp False

To see whether something appears as a value in a dictionary, you can use the method values, which returns the values as a list, and then use the in operator:

>>> vals = eng2sp.values() >>> 'uno' in vals True

The in operator uses different algorithms for lists and dictionaries. For lists, it uses a search algorithm, as in Section 8.6. As the list gets longer, the search time gets longer in direct proportion. For dictionaries, Python uses an algorithm called a hashtable that has a remarkable property: the in operator takes about the same amount of time no matter how many items there are in a dictionary. I won’t explain how that’s possible, but you can read more about it at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hash_table.

11.1 Dictionary as a set of counters

Suppose you are given a string and you want to count how many times each letter appears.

There are several ways you could do it:

- You could create 26 variables, one for each letter of the alphabet. Then you could traverse the string and, for each character, increment the corresponding counter, probably using a chained conditional.

- You could create a list with 26 elements. Then you could convert each character to a number (using the built-in function ord), use the number as an index into the list, and increment the appropriate counter.

- You could create a dictionary with characters as keys and counters as the corresponding values. The first time you see a character, you would add an item to the dictionary.

After that you would increment the value of an existing item.

Each of these options performs the same computation, but each of them implements that computation in a different way.

An implementation is a way of performing a computation; some implementations are better than others. For example, an advantage of the dictionary implementation is that we don’t have to know ahead of time which letters appear in the string and we only have to make room for the letters that do appear.

Here is what the code might look like:

def histogram(s): d = dict() for c in s: if c not in d: d[c] = 1 else: d[c] += 1 return d

The name of the function is histogram, which is a statistical term for a set of counters (or frequencies).

The first line of the function creates an empty dictionary. The for loop traverses the string.

Each time through the loop, if the character c is not in the dictionary, we create a new item with key c and the initial value 1 (since we have seen this letter once). If c is already in the dictionary we increment d[c].

Here’s how it works:

>>> h = histogram('brontosaurus') >>> print h {'a': 1, 'b': 1, 'o': 2, 'n': 1, 's': 2, 'r': 2, 'u': 2, 't': 1}

The histogram indicates that the letters 'a' and 'b' appear once; 'o' appears twice, and so on.

11.2 Looping and dictionaries

If you use a dictionary in a for statement, it traverses the keys of the dictionary. For example, print_hist prints each key and the corresponding value:

def print_hist(h): for c in h: print c, h[c]

Here’s what the output looks like:

>>> h = histogram('parrot') >>> print_hist(h) a 1 p 1 r 2 t 1 o 1

Again, the keys are in no particular order.

Exercise 11.3. Dictionaries have a method called keys that returns the keys of the dictionary, in no particular order, as a list.

Modify print_hist to print the keys and their values in alphabetical order.

11.3 Reverse lookup

Given a dictionary d and a key k, it is easy to find the corresponding value v = d[k]. This operation is called a lookup.

But what if you have v and you want to find k? You have two problems: first, there might be more than one key that maps to the value v. Depending on the application, you might be able to pick one, or you might have to make a list that contains all of them. Second, there is no simple syntax to do a reverse lookup; you have to search.

Here is a function that takes a value and returns the first key that maps to that value:

def reverse_lookup(d, v): for k in d: if d[k] == v: return k

raise ValueError

This function is yet another example of the search pattern, but it uses a feature we haven’t seen before, raise. The raise statement causes an exception; in this case it causes a ValueError, which generally indicates that there is something wrong with the value of

a parameter.

If we get to the end of the loop, that means v doesn’t appear in the dictionary as a value, so we raise an exception.

Here is an example of a successful reverse lookup:

>>> h = histogram('parrot') >>> k = reverse_lookup(h, 2) >>> print k r

And an unsuccessful one:

>>> k = reverse_lookup(h, 3)

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in ? File "<stdin>", line 5, in reverse_lookup ValueError

The result when you raise an exception is the same as when Python raises one: it prints a traceback and an error message.

The raise statement takes a detailed error message as an optional argument. For example:

>>> raise ValueError('value does not appear in the dictionary')

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in ? ValueError: value does not appear in the dictionary

A reverse lookup is much slower than a forward lookup; if you have to do it often, or if the dictionary gets big, the performance of your program will suffer.

11.4 Dictionaries and lists

Lists can appear as values in a dictionary. For example, if you were given a dictionary that maps from letters to frequencies, you might want to invert it; that is, create a dictionary that maps from frequencies to letters. Since there might be several letters with the same frequency, each value in the inverted dictionary should be a list of letters.

Here is a function that inverts a dictionary:

def invert_dict(d): inverse = dict() for key in d: val = d[key] if val not in inverse: inverse[val] = [key] else: inverse[val].append(key) return inverse

Each time through the loop, key gets a key from d and val gets the corresponding value.

If val is not in inverse, that means we haven’t seen it before, so we create a new item and initialize it with a singleton (a list that contains a single element). Otherwise we have seen this value before, so we append the corresponding key to the list.

Here is an example:

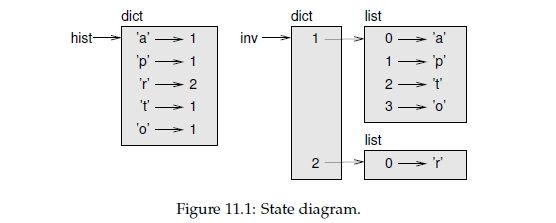

>>> hist = histogram('parrot') >>> print hist {'a': 1, 'p': 1, 'r': 2, 't': 1, 'o': 1} >>> inverse = invert_dict(hist) >>> print inverse {1: ['a', 'p', 't', 'o'], 2: ['r']}

Figure 11.1 is a state diagram showing hist and inverse. A dictionary is represented as a box with the type dict above it and the key-value pairs inside. If the values are integers, floats or strings, I usually draw them inside the box, but I usually draw lists outside the

box, just to keep the diagram simple.

Lists can be values in a dictionary, as this example shows, but they cannot be keys. Here’s what happens if you try:

>>> t = [1, 2, 3] >>> d = dict() >>> d[t] = 'oops' Traceback (most recent call last): File "<stdin>", line 1, in ? TypeError: list objects are unhashable

I mentioned earlier that a dictionary is implemented using a hashtable and that means that the keys have to be hashable.

A hash is a function that takes a value (of any kind) and returns an integer. Dictionaries use these integers, called hash values, to store and look up key-value pairs.

This system works fine if the keys are immutable. But if the keys are mutable, like lists, bad things happen. For example, when you create a key-value pair, Python hashes the key and stores it in the corresponding location. If you modify the key and then hash it again, it would go to a different location. In that case you might have two entries for the same key, or you might not be able to find a key. Either way, the dictionary wouldn’t work correctly.

That’s why the keys have to be hashable, and why mutable types like lists aren’t. The simplest way to get around this limitation is to use tuples, which we will see in the next chapter.

Since dictionaries are mutable, they can’t be used as keys, but they can be used as values.

11.5 Memos

If you played with the fibonacci function from Section 6.7, you might have noticed that the bigger the argument you provide, the longer the function takes to run. Furthermore, the run time increases very quickly.

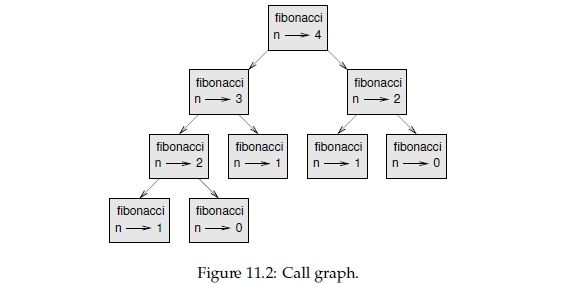

To understand why, consider Figure 11.2, which shows the call graph for fibonacci with n=4:

A call graph shows a set of function frames, with lines connecting each frame to the frames of the functions it calls. At the top of the graph, fibonacci with n=4 calls fibonacci with n=3 and n=2. In turn, fibonacci with n=3 calls fibonacci with n=2 and n=1. And so on.

Count how many times fibonacci(0) and fibonacci(1) are called. This is an inefficient solution to the problem, and it gets worse as the argument gets bigger.

One solution is to keep track of values that have already been computed by storing them in a dictionary. A previously computed value that is stored for later use is called a memo.

Here is a “memoized” version of fibonacci:

known = {0:0, 1:1}

def fibonacci(n):

if n in known:

return known[n]

res = fibonacci(n-1) + fibonacci(n-2)

known[n] = res

return res

known is a dictionary that keeps track of the Fibonacci numbers we already know. It starts with two items: 0 maps to 0 and 1 maps to 1.

Whenever fibonacci is called, it checks known. If the result is already there, it can return immediately. Otherwise it has to compute the new value, add it to the dictionary, and return it.

11.6 Global variables

In the previous example, known is created outside the function, so it belongs to the special frame called __main__. Variables in __main__ are sometimes called global because they can be accessed from any function. Unlike local variables, which disappear when their function ends, global variables persist from one function call to the next. It is common to use global variables for flags; that is, boolean variables that indicate (“flag”) whether a condition is true. For example, some programs use a flag named verbose to control the level of detail in the output:

verbose = True def example1(): if verbose: print 'Running example1'

If you try to reassign a global variable, you might be surprised. The following example is supposed to keep track of whether the function has been called:

been_called = False def example2(): been_called = True # WRONG

But if you run it you will see that the value of been_called doesn’t change. The problem is that example2 creates a new local variable named been_called. The local variable goes away when the function ends, and has no effect on the global variable.

To reassign a global variable inside a function you have to declare the global variable before you use it:

been_called = False def example2(): global been_called been_called = True

The global statement tells the interpreter something like, “In this function, when I say been_called, I mean the global variable; don’t create a local one.”

Here’s an example that tries to update a global variable:

count = 0 def example3(): count = count + 1 # WRONG

If you run it you get:

UnboundLocalError: local variable 'count' referenced before assignment

Python assumes that count is local, which means that you are reading it before writing it.

The solution, again, is to declare count global.

def example3(): global count count += 1

If the global value is mutable, you can modify it without declaring it:

known = {0:0, 1:1}

def example4():

known[2] = 1

So you can add, remove and replace elements of a global list or dictionary, but if you want to reassign the variable, you have to declare it:

def example5(): global known known = dict()

11.7 Long integers

If you compute fibonacci(50), you get:

>>> fibonacci(50)

12586269025L

The L at the end indicates that the result is a long integer, or type long. In Python 3, long is gone; all integers, even really big ones, are type int.

Values with type int have a limited range; long integers can be arbitrarily big, but as they get bigger they consume more space and time.

The mathematical operators work on long integers, and the functions in the math module, too, so in general any code that works with int will also work with long.

Any time the result of a computation is too big to be represented with an integer, Python converts the result as a long integer:

>>> 1000 * 1000 1000000 >>> 100000 * 100000 10000000000L

In the first case the result has type int; in the second case it is long.