Flow control statements: for, if , else, switch and defer

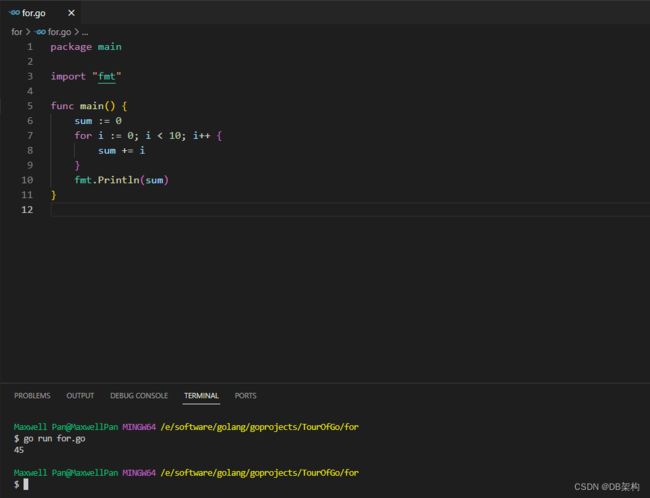

1.For

Go has only one looping construct, the for loop.

The basic for loop has three components separated by semicolons:

- the init statement: executed before the first iteration

- the condition expression: evaluated before every iteration

- the post statement: executed at the end of every iteration

The init statement will often be a short variable declaration, and the variables declared there are visible only in the scope of the for statement.

The loop will stop iterating once the boolean condition evaluates to false.

Note: Unlike other languages like C, Java, or JavaScript there are no parentheses surrounding the three components of the for statement and the braces { } are always required.

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

sum := 0

for i := 0; i < 10; i++ {

sum += i

}

fmt.Println(sum)

}2. For continued

The init and post statements are optional.

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

sum := 1

for sum < 1000 {

sum += sum

}

fmt.Println(sum)

}

3.For is Go's "while"

At that point you can drop the semicolons: C's while is spelled for in Go.

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

sum := 1

for sum < 1000 {

sum += sum

}

fmt.Println(sum)

}

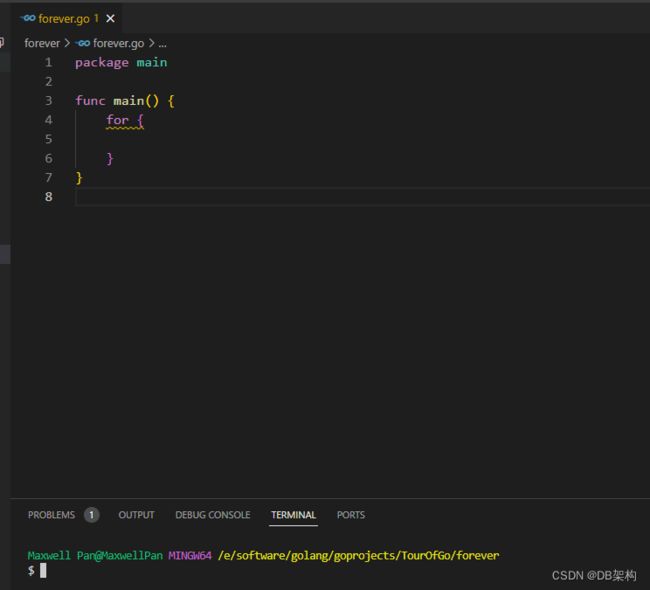

4. Forever

If you omit the loop condition it loops forever, so an infinite loop is compactly expressed.

package main

func main() {

for {

}

}

5.If

Go's if statements are like its for loops; the expression need not be surrounded by parentheses ( ) but the braces { } are required.

package main

import (

"fmt"

"math"

)

func sqrt(x float64) string {

if x < 0 {

return sqrt(-x) + "i"

}

return fmt.Sprint(math.Sqrt(x))

}

func main() {

fmt.Println(sqrt(2), sqrt(-4))

}

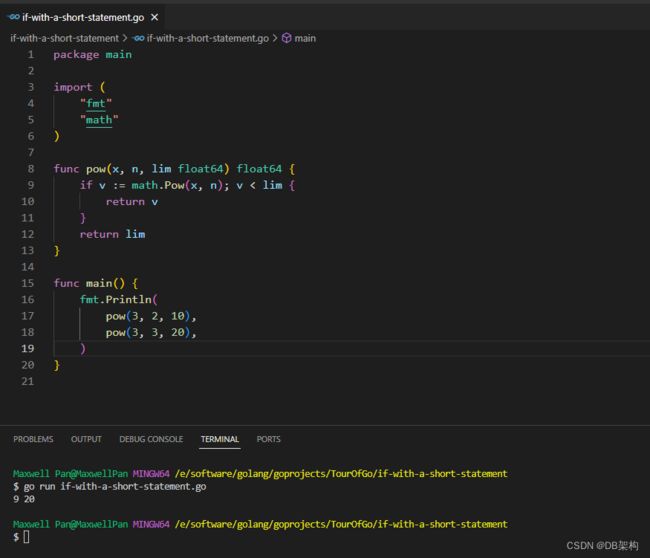

6. If with a short statement

Like for, the if statement can start with a short statement to execute before the condition.

Variables declared by the statement are only in scope until the end of the if.

(Try using v in the last return statement.)

package main

import (

"fmt"

"math"

)

func pow(x, n, lim float64) float64 {

if v := math.Pow(x, n); v < lim {

return v

}

return lim

}

func main() {

fmt.Println(

pow(3, 2, 10),

pow(3, 3, 20),

)

}

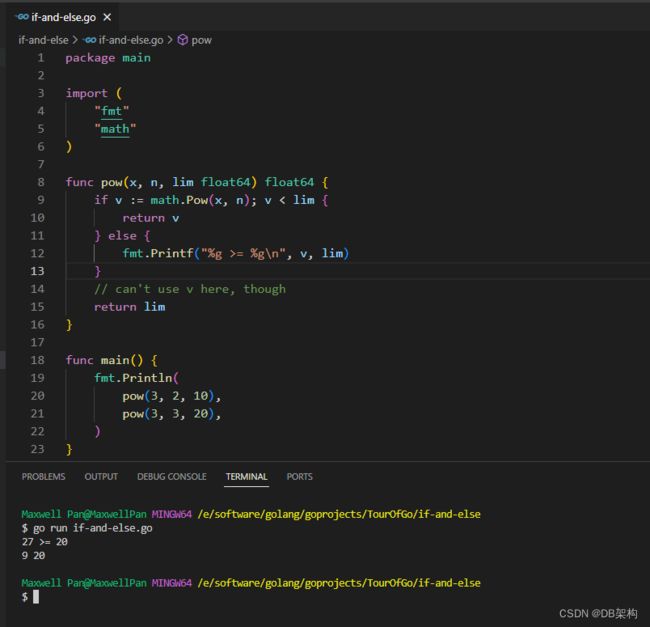

7.If and else

Variables declared inside an if short statement are also available inside any of the else blocks.

(Both calls to pow return their results before the call to fmt.Println in main begins.)

package main

import (

"fmt"

"math"

)

func pow(x, n, lim float64) float64 {

if v := math.Pow(x, n); v < lim {

return v

} else {

fmt.Printf("%g >= %g\n", v, lim)

}

// can't use v here, though

return lim

}

func main() {

fmt.Println(

pow(3, 2, 10),

pow(3, 3, 20),

)

}

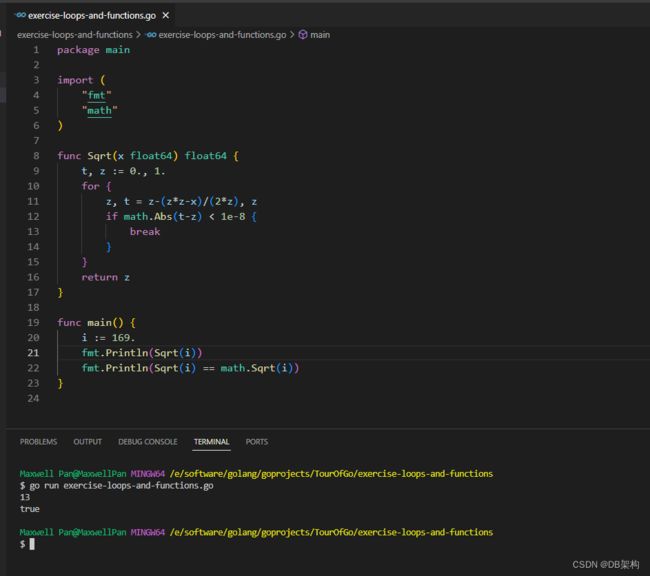

8. Exercise: Loops and Functions

As a way to play with functions and loops, let's implement a square root function: given a number x, we want to find the number z for which z² is most nearly x.

Computers typically compute the square root of x using a loop. Starting with some guess z, we can adjust z based on how close z² is to x, producing a better guess:

z -= (z*z - x) / (2*z)

Repeating this adjustment makes the guess better and better until we reach an answer that is as close to the actual square root as can be.

Implement this in the func Sqrt provided. A decent starting guess for z is 1, no matter what the input. To begin with, repeat the calculation 10 times and print each z along the way. See how close you get to the answer for various values of x (1, 2, 3, ...) and how quickly the guess improves.

Hint: To declare and initialize a floating point value, give it floating point syntax or use a conversion:

z := 1.0 z := float64(1)

Next, change the loop condition to stop once the value has stopped changing (or only changes by a very small amount). See if that's more or fewer than 10 iterations. Try other initial guesses for z, like x, or x/2. How close are your function's results to the math.Sqrt in the standard library?

(Note: If you are interested in the details of the algorithm, the z² − x above is how far away z² is from where it needs to be (x), and the division by 2z is the derivative of z², to scale how much we adjust z by how quickly z² is changing. This general approach is called Newton's method. It works well for many functions but especially well for square root.)

package main

import (

"fmt"

"math"

)

func Sqrt(x float64) float64 {

t, z := 0., 1.

for {

z, t = z-(z*z-x)/(2*z), z

if math.Abs(t-z) < 1e-8 {

break

}

}

return z

}

func main() {

i := 169.

fmt.Println(Sqrt(i))

fmt.Println(Sqrt(i) == math.Sqrt(i))

}

9.Switch

A switch statement is a shorter way to write a sequence of if - else statements. It runs the first case whose value is equal to the condition expression.

Go's switch is like the one in C, C++, Java, JavaScript, and PHP, except that Go only runs the selected case, not all the cases that follow. In effect, the break statement that is needed at the end of each case in those languages is provided automatically in Go. Another important difference is that Go's switch cases need not be constants, and the values involved need not be integers.

package main

import (

"fmt"

"runtime"

)

func main() {

fmt.Print("Go runs on ")

switch os := runtime.GOOS; os {

case "darwin":

fmt.Println("OS X.")

case "linux":

fmt.Println("Linux.")

default:

// freebsd, openbsd,

// plan9, windows...

fmt.Printf("%s.\n", os)

}

}

10. Switch evaluation order

Switch cases evaluate cases from top to bottom, stopping when a case succeeds.

(For example,

switch i {

case 0:

case f():

}

does not call f if i==0.)

Note: Time in the Go playground always appears to start at 2009-11-10 23:00:00 UTC, a value whose significance is left as an exercise for the reader.

package main

import (

"fmt"

"time"

)

func main() {

fmt.Println("When's Saturday?")

today := time.Now().Weekday()

switch time.Saturday {

case today + 0:

fmt.Println("Today.")

case today + 1:

fmt.Println("Tomorrow.")

case today + 2:

fmt.Println("In two days.")

default:

fmt.Println("Too far away.")

}

}

11.Switch with no condition

Switch without a condition is the same as switch true.

This construct can be a clean way to write long if-then-else chains.

package main

import (

"fmt"

"time"

)

func main() {

t := time.Now()

switch {

case t.Hour() < 12:

fmt.Println("Good morning!")

case t.Hour() < 17:

fmt.Println("Good afternoon.")

default:

fmt.Println("Good evening.")

}

}

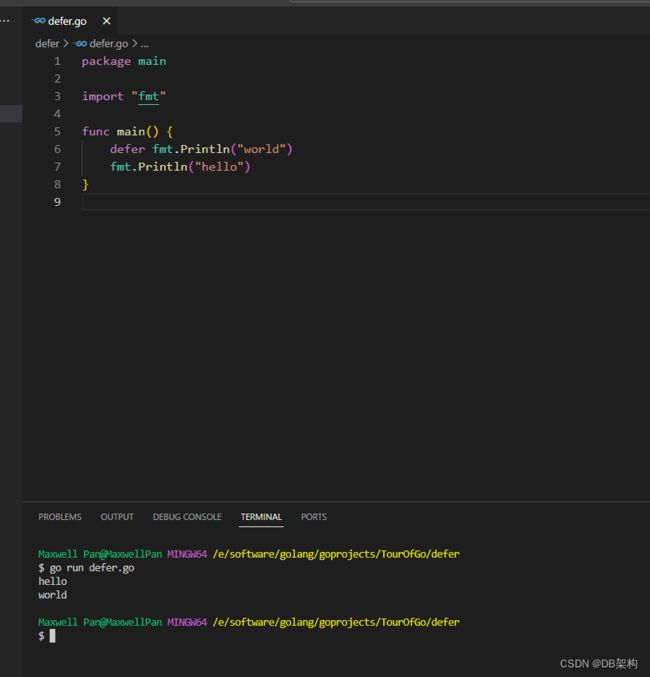

12.Defer

A defer statement defers the execution of a function until the surrounding function returns.

The deferred call's arguments are evaluated immediately, but the function call is not executed until the surrounding function returns.

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

defer fmt.Println("world")

fmt.Println("hello")

}

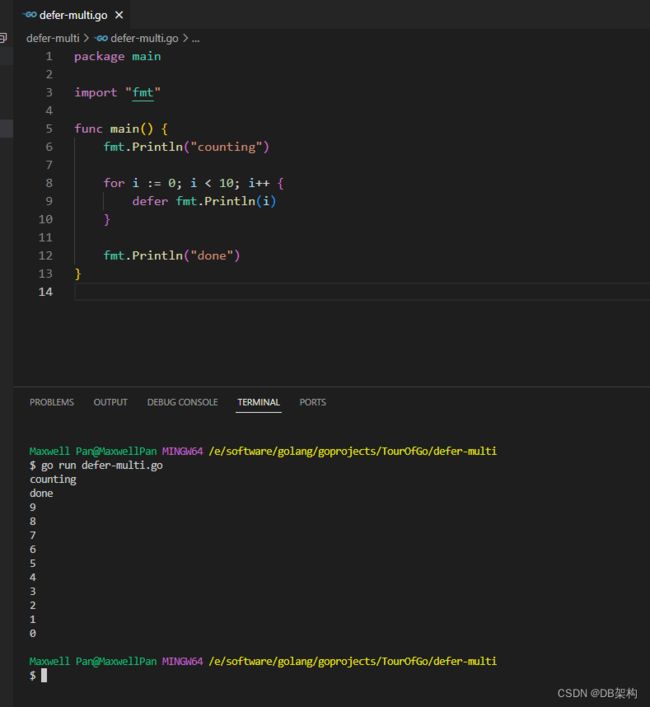

13. Stacking defers

Deferred function calls are pushed onto a stack. When a function returns, its deferred calls are executed in last-in-first-out order.

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

fmt.Println("counting")

for i := 0; i < 10; i++ {

defer fmt.Println(i)

}

fmt.Println("done")

}