Methods and Interfaces Part2

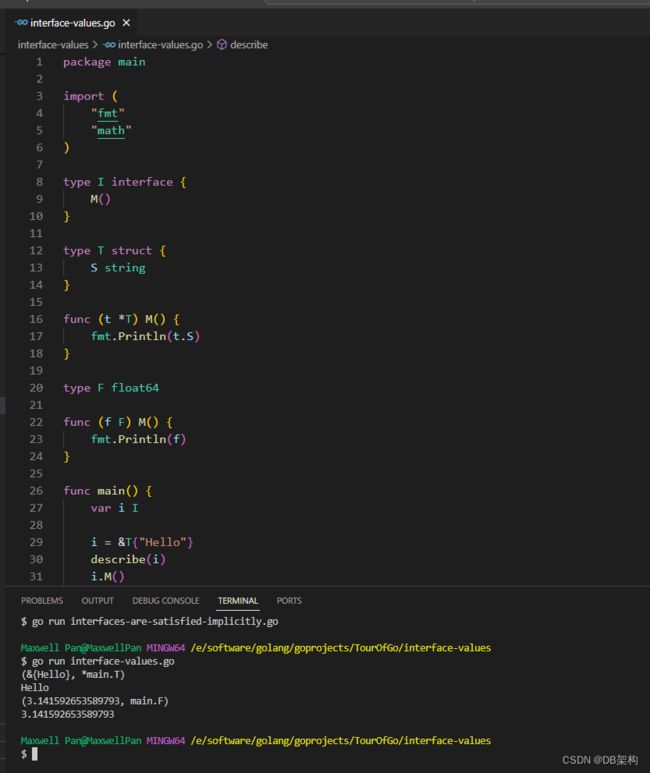

1.Interface values

Under the hood, interface values can be thought of as a tuple of a value and a concrete type:

(value, type)

An interface value holds a value of a specific underlying concrete type.

Calling a method on an interface value executes the method of the same name on its underlying type.

package main

import (

"fmt"

"math"

)

type I interface {

M()

}

type T struct {

S string

}

func (t *T) M() {

fmt.Println(t.S)

}

type F float64

func (f F) M() {

fmt.Println(f)

}

func main() {

var i I

i = &T{"Hello"}

describe(i)

i.M()

i = F(math.Pi)

describe(i)

i.M()

}

func describe(i I) {

fmt.Printf("(%v, %T)\n", i, i)

}

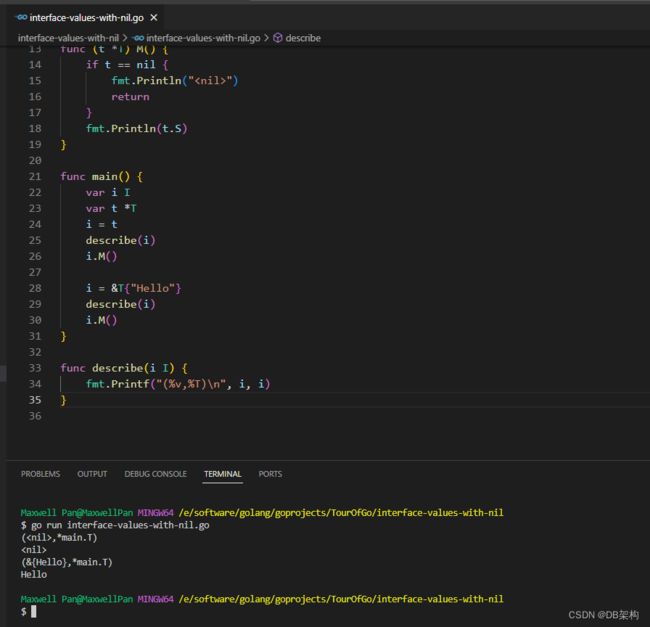

2. Interface values with nil underlying values

If the concrete value inside the interface itself is nil, the method will be called with a nil receiver.

In some languages this would trigger a null pointer exception, but in Go it is common to write methods that gracefully handle being called with a nil receiver (as with the method M in this example.)

Note that an interface value that holds a nil concrete value is itself non-nil.

package main

import "fmt"

type I interface {

M()

}

type T struct {

S string

}

func (t *T) M() {

if t == nil {

fmt.Println("")

return

}

fmt.Println(t.S)

}

func main() {

var i I

var t *T

i = t

describe(i)

i.M()

i = &T{"Hello"}

describe(i)

i.M()

}

func describe(i I) {

fmt.Printf("(%v,%T)\n", i, i)

}

3. Nil interface values

A nil interface value holds neither value nor concrete type.

Calling a method on a nil interface is a run-time error because there is no type inside the interface tuple to indicate which concrete method to call.

package main

import "fmt"

type I interface {

M()

}

func main() {

var i I

describe(i)

i.M()

}

func describe(i I) {

fmt.Printf("(%v,%T)\n", i, i)

}

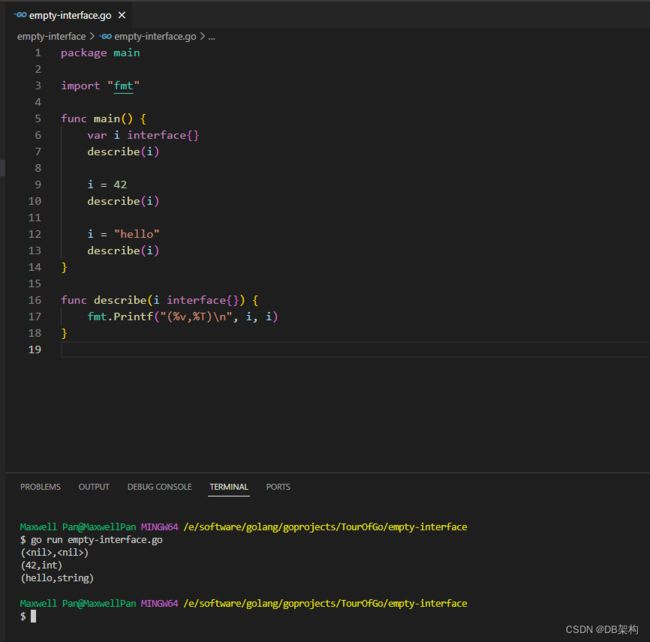

4.The empty interface

The interface type that specifies zero methods is known as the empty interface:

interface{}

An empty interface may hold values of any type. (Every type implements at least zero methods.)

Empty interfaces are used by code that handles values of unknown type. For example, fmt.Print takes any number of arguments of type interface{}.

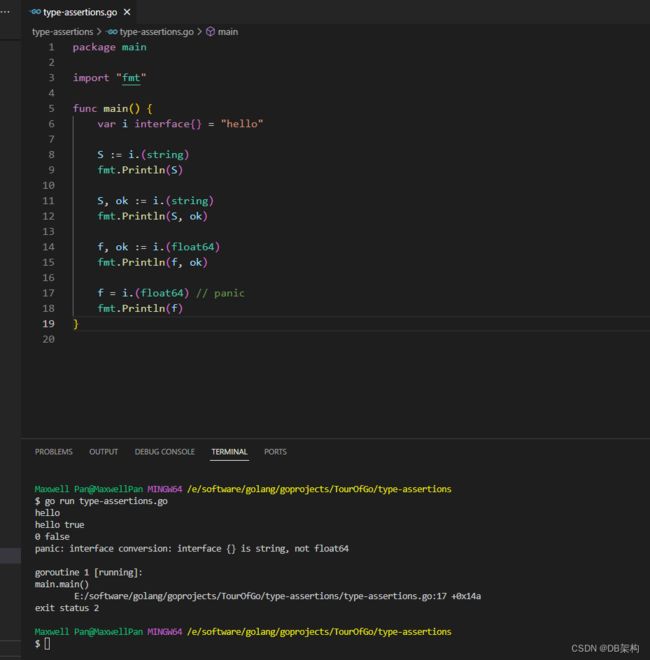

5.Type assertions

A type assertion provides access to an interface value's underlying concrete value.

t := i.(T)

This statement asserts that the interface value i holds the concrete type T and assigns the underlying T value to the variable t.

If i does not hold a T, the statement will trigger a panic.

To test whether an interface value holds a specific type, a type assertion can return two values: the underlying value and a boolean value that reports whether the assertion succeeded.

t, ok := i.(T)

If i holds a T, then t will be the underlying value and ok will be true.

If not, ok will be false and t will be the zero value of type T, and no panic occurs.

Note the similarity between this syntax and that of reading from a map.

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

var i interface{} = "hello"

S := i.(string)

fmt.Println(S)

S, ok := i.(string)

fmt.Println(S, ok)

f, ok := i.(float64)

fmt.Println(f, ok)

f = i.(float64) // panic

fmt.Println(f)

}

6.Type switches

A type switch is a construct that permits several type assertions in series.

A type switch is like a regular switch statement, but the cases in a type switch specify types (not values), and those values are compared against the type of the value held by the given interface value.

switch v := i.(type) {

case T:

// here v has type T

case S:

// here v has type S

default:

// no match; here v has the same type as i

}

The declaration in a type switch has the same syntax as a type assertion i.(T), but the specific type T is replaced with the keyword type.

This switch statement tests whether the interface value i holds a value of type T or S. In each of the T and S cases, the variable v will be of type T or S respectively and hold the value held by i. In the default case (where there is no match), the variable v is of the same interface type and value as i.

package main

import "fmt"

func do(i interface{}) {

switch v := i.(type) {

case int:

fmt.Printf("Twice %v is %v\n", v, v*2)

case string:

fmt.Printf("%q is %v bytes long\n", v, len(v))

default:

fmt.Printf("I don't know about type %T!\n", v)

}

}

func main() {

do(21)

do("hello")

do(true)

}