Data Structures, Algorithms, & Applications in Java

Have You Seen This String?

The Suffix Tree

Let's Find That Substring

Other Nifty Things You Can Do with a Suffix Tree

How to Build Your Very Own Suffix Tree

Exercises

References and Selected Readings

Have You Seen This String?

In the classical substring search problem, we are given a string

S and a pattern

P and are to report whether or not the pattern

P occurs in the string

S. For example, the pattern

P = cat appears (twice) in the string

S1 = The big cat ate the small catfish., but does not appear in the string

S2 = Dogs for sale..

Researchers in the human genome project are constantly searching for substrings/patterns (we use the terms substring and pattern interchangeably) in a gene databank that contains tens of thousands of genes. Each gene is represented as a sequence or string of letters drawn from the alphabet

{A, C, G, T}. Although, most of the strings in the databank are around

2000 letters long, some have tens of thousands of letters. Because of the size of the gene databank and the frequency with which substring searches are done, it is imperitive that we have as fast an algorithm as possible to locate a given substring within the strings in the databank.

We can search for a pattern

P in a string

S, using pattern matching algorithms that are described in standard

algorithm's texts. The complexity of such a search is

O(|P| + |S|), where

|P| denotes the length (i.e., number of letters or digits) of

P. This complexity looks pretty good when you consider that the pattern

P could appear anywhere in the string

S. Therefore, we must examine every letter/digit (we use the terms letter and digit interchangeably) of the string before we can conclude that the search pattern does not appear in the string. Further, before we can conclude that the search pattern appears in the string, we must examine every digit of the pattern. Hence, every pattern search algorithm must take time that is linear in the lengths of the pattern and the string being searched.

When classical pattern matching algorithms are used to search for several patterns

P1, P2, ..., Pk in the string

S,

O(|P1| + |P2| + ... + |Pk| + k|S|) time is taken (because

O(|Pi| + |S|) time is taken to seach for

Pi). The suffix tree data structure that we are about to study reduces this complexity to

O(|P1| + |P2| + ... + |Pk| + |S|). Of this time,

O(|S|) time is spent setting up the suffix tree for the string

S; an individual pattern search takes only

O(|Pi|) time (after the suffix tree for

S has been built). Therefore once the suffix tree for

S has been created, the time needed to search for a pattern depends only on the length of the pattern.

The Suffix Tree

The suffix tree for

S is actually the

compressed trie for the nonempty suffixes of the string

S. Since a suffix tree is a compressed trie, we sometimes refer to the tree as a trie and to its subtrees as subtries.

The (nonempty) suffixes of the string

S = peeper are

peeper, eeper, eper, per, er, and

r. Therefore, the suffix tree for the string

pepper is the compressed trie that contains the elements (which are also the keys)

peeper, eeper, eper, per, er, and

r. The alphabet for the string

peeper is

{e, p, r}. Therefore, the radix of the compressed trie is

3. If necessary, we may use the mapping

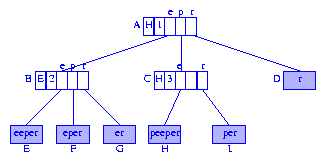

e -> 0, p -> 1, r -> 2, to convert from the letters of the string to numbers. This conversion is necessary only when we use a node structure in which each node has an array of child pointers. Figure 1 shows the compressed trie (with edge information) for the suffixes of

peeper. This compressed trie is also the suffix tree for the string

peeper.

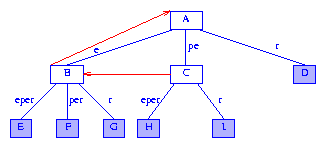

Figure 1 Compressed trie for the suffixes of peeper

Since the data in the information nodes

D-I are the suffixes of

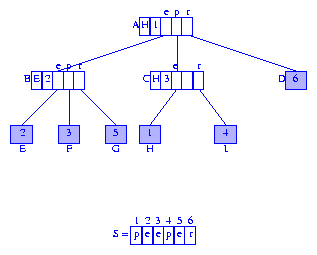

peeper, each information node need retain only the start index of the suffix it contains. When the letters in

peeper are indexed from left to right beginning with the index

1, the information nodes

D-I need only retain the indexes

6, 2, 3, 5, 1, and

4, respectively. Using the index stored in an information node, we can access the suffix from the string

S. Figure 2 shows the suffix tree of Figure 1 with each information node containing a suffix index.

Figure 2 Modified compressed trie for the suffixes of peeper

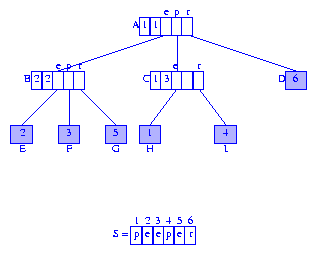

The first component of each branch node is a reference to an element in that subtrie. We may replace the element reference by the index of the first digit of the referenced element. Figure 3 shows the resulting compressed trie. We shall use this modified form as the representation for the suffix tree.

Figure 3 Suffix tree for peeper

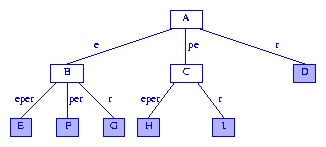

When describing the search and construction algorithms for suffix trees, it is easier to deal with a drawing of the suffix tree in which the edges are labeled by the digits used in the move from a branch node to a child node. The first digit of the label is the digit used to determine which child is moved to, and the remaining digits of the label give the digits that are skipped over. Figure 4 shows the suffix tree of Figure 3 drawn in this manner.

Figure 4 A more humane drawing of a suffix tree

In the more humane drawing of a suffix tree, the labels on the edges on any root to information node path spell out the suffix represented by that information node. When the digit number for the root is not

1, the humane drawing of a suffix tree includes a head node with an edge to the former root. This edge is labeled with the digits that are skipped over.

The string represented by a node of a suffix tree is the string spelled by the labels on the path from the root to that node. Node

A of Figure 4 represents the empty string

epsilon, node

C represents the string

pe, and node

F represents the string

eper.

Since the keys in a suffix tree are of different length, we must ensure that no key is a proper prefix of another (see Keys With Different Length). Whenever the last digit of string

S appears only once in

S, no suffix of

S can be a proper prefix of another suffix of

S. In the string

peeper, the last digit is

r, and this digit appears only once. Therefore, no suffix of

peeper is a proper prefix of another. The last digit of

data is

a, and this last digit appears twice in

data. Therefore,

data has two suffixes

ata and

a that begin with

a. The suffix

a is a proper prefix of the suffix

ata.

When the last digit of the string

S appears more than once in

S we must append a new digit (say

#) to the suffixes of

S so that no suffix is a prefix of another. Optionally, we may append the new digit to

S to get the string

S#, and then construct the suffix tree for

S#. When this optional route is taken, the suffix tree has one more suffix (

#) than the suffix tree obtained by appending the symbol

# to the suffixes of

S.

Let's Find That Substring

But First, Some Terminology

Let

n = |S| denote the length (i.e., number of digits) of the string whose suffix tree we are to build. We number the digits of

S from left to right beginning with the number

1.

S[i] denotes the

ith digit of

S, and

suffix(i) denotes the suffix

S[i]...S[n] that begins at digit

i,

1 <= i <= n.

On With the Search

A fundamental observation used when searching for a pattern

P in a string

S is that

P appears in

S (i.e.,

P is a substring of

S) iff

P is a prefix of some suffix of

S.

Suppose that

P = P[1]...P[k] = S[i]...S[i+k-1]. Then,

P is a prefix of

suffix(i). Since

suffix(i) is in our compressed trie (i.e., suffix tree), we can search for

P by using the

strategy to search for a key prefix in a compressed trie.

Let's search for the pattern

P = per in the string

S = peeper. Imagine that we have already constructed the suffix tree (Figure 4) for

peeper. The search starts at the root node

A. Since

P[1] = p, we follow the edge whose label begins with the digit

p. When following this edge, we compare the remaining digits of the edge label with successive digits of

P. Since these remaining label digits agree with the pattern digits, we reach the branch node

C. In getting to node

C, we have used the first two digits of the pattern. The third digit of the pattern is

r, and so, from node

C we follow the edge whose label begins with

r. Since this edge has no additional digits in its label, no additional digit comparisons are done and we reach the information node

I. At this time, the digits in the pattern have been exhausted and we conclude that the pattern is in the string. Since an information node is reached, we conclude that the pattern is actually a suffix of the string

peeper. In the actual suffix tree representation (rather than in the humane drawing), the information node

I contains the index

4 which tells us that the pattern

P = per begins at digit

4 of

peeper (i.e.,

P = suffix(4)). Further, we can conclude that

per appears exactly once in

peeper; the search for a pattern that appears more than once terminates at a branch node, not at an information node.

Now, let us search for the pattern

P = eeee. Again, we start at the root. Since the first character of the pattern is

e, we follow the edge whose label begins with

e and reach the node

B. The next digit of the pattern is also

e, and so, from node

B we follow the edge whose label begins with

e. In following this edge, we must compare the remaining digits

per of the edge label with the following digits

ee of the pattern. We find a mismatch when the first pair

(p,e) of digits are compared and we conclude that the pattern does not appear in

peeper.

Suppose we are to search for the pattern

P = p. From the root, we follow the edge whose label begins with

p. In following this edge, we compare the remaining digits (only the digit

e remains) of the edge label with the following digits (there aren't any) of the pattern. Since the pattern is exhausted while following this edge, we conclude that the pattern is a prefix of all keys in the subtrie rooted at node

C. We can find all occurrences of the pattern by traversing the subtrie rooted at

C and visiting the information nodes in this subtrie. If we want the location of just one of the occurrences of the pattern, we can use the index stored in the first component of the branch node

C (see Figure 3). When a pattern exhausts while following the edge to node

X, we say that node

X has been reached; the search terminates at node

X.

When searching for the pattern

P = rope, we use the first digit

r of

P and reach the information node

D. Since the the pattern has not been exhausted, we must check the remaining digits of the pattern against those of the key in

D. This check reveals that the pattern is not a prefix of the key in

D, and so the pattern does not appear in

peeper.

The last search we are going to do is for the pattern

P = pepe. Starting at the root of Figure 4, we move over the edge whose label begins with

p and reach node

C. The next unexamined digit of the search pattern is

p. So, from node

C, we wish to follow the edge whose label begins with

p. Since no edge satisfies this requirement, we conclude that

pepe does not appear in the string

peeper.

Other Nifty Things You Can Do with a Suffix Tree

Once we have set up the suffix tree for a string

S, we can tell whether or not

S contains a pattern

P in

O(|P|) time. This means that if we have a suffix tree for the text of Shakespeare's play ``Romeo and Juliet,'' we can determine whether or not the phrase

wherefore art thou appears in this play with lightning speed. In fact, the time taken will be that needed to compare up to

18 (the length of the search pattern) letters/digits. The search time is independent of the length of the play.

Other interesting things you can do at lightning speed are:

- Find all occurrences of a pattern

P. This is done by searching the suffix tree forP. IfPappears at least once, the search terminates successfully either at an information node or at a branch node. When the search terminates at an information node, the pattern occurs exactly once. When we terminate at a branch nodeX, all places where the pattern occurs can be found by visiting the information nodes in the subtrie rooted atX. This visiting can be done in time linear in the number of occurrences of the pattern if we- (a)

-

Link all of the information nodes in the suffix tree into a chain, the linking is done in lexicographic order of the represented suffixes (which also is the order in which the information nodes are encountered in a left to right scan of the information nodes). The information nodes of Figure 4 will be linked in the order

E, F, G, H, I, D. - (b)

-

In each branch node, keep a reference to the first and last information node in the subtrie of which that branch node is the root. In Figure 4, nodes

A, B,andCkeep the pairs(E, D), (E, G),and(H,I), respectively. We use the pair(firstInformationNode, lastInformationNode)to traverse the information node chain starting atfirstInformationNodeand ending atlastInformationNode. This traversal yields all occurrences of patterns that begin with the string spelled by the edge labels from the root to the branch node. Notice that when(firstInformationNode, lastInformationNode)pairs are kept in branch nodes, we can eliminate the branch node field that keeps a reference to an information node in the subtrie (i.e., the fieldelement).

- Find all strings that contain a pattern

P. Suppose we have a collectionS1, S2, ... Skof strings and we wish to report all strings that contain a query patternP. For example, the genome databank contains tens of thousands of strings, and when a researcher submits a query string, we are to report all databank strings that contain the query string. To answer queries of this type efficiently, we set up a compressed trie (we may call this a multiple string suffix tree) that contains the suffixes of the stringS1$S2$...$Sk#, where$and#are two different digits that do not appear in any of the stringsS1, S2, ..., Sk. In each node of the suffix tree, we keep a list of all stringsSithat are the start point of a suffix represented by an information node in that subtrie.

- Find the longest substring of

Sthat appears at leastm > 1times. This query can be answered inO(|S|)time in the following way:- (a)

- Traverse the suffix tree labeling the branch nodes with the sum of the label lengths from the root and also with the number of information nodes in the subtrie.

- (b)

-

Traverse the suffix tree visiting branch nodes with information node count

>= m. Determine the visited branch node with longest label length.

Note that step (a) needs to be done only once. Following this, we can do step (b) for as many values ofmas is desired. Also, note that whenm = 2we can avoid determining the number of information nodes in subtries. In a compressed trie, every subtrie rooted at a branch node has at least two information nodes in it.

- Find the longest common substring of the strings

SandT. This can be done in timeO(|S| + |T|)as below:- (a)

-

Construct a multiple string suffix tree for

SandT(i.e., the suffix tree forS$T#). - (b)

-

Traverse the suffix tree to identify the branch node for which the sum of the label lengths on the path from the root is maximum and whose subtrie has at least one information node that represents a suffix that begins in

Sand at least one information node that represents a suffix that begins inT.

Notice that the related problem to find the longest common subsequence ofSandTis solved inO(|S| * |T|)time using dynamic programming (see Exercise 15.22 of the text).

How to Build Your Very Own Suffix Tree

Three Observations

To aid in the construction of the suffix tree, we add a

longestProperSuffix field to each branch node. The

longestProperSuffix field of a branch node that represents the nonempty string

Y points to the branch node for the longest proper suffix of

Y (this suffix is obtained by removing the first digit from

Y). The

longestProperSuffix field of the root is not used.

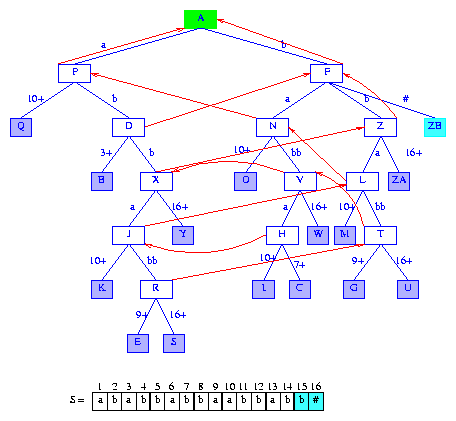

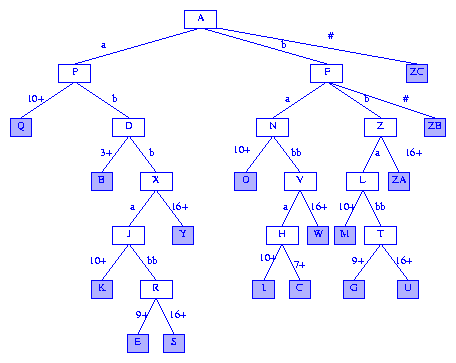

Figure 5 shows the suffix tree of Figure 4 with longest proper suffix pointers (often, we refer to the longest proper suffix pointer as simply the suffix pointer) included. Longest proper suffix pointers are shown as red arrows. Node

C represents the string

pe. The longest proper suffix

e of

pe is represented by node

B. Therefore, the (longest proper) suffix pointer of

C points to node

B. The longest proper suffix of the string

e represented by node

B is the empty string. Since the root node represents the empty string, the longest proper suffix pointer of node

B points to the root node

A.

Figure 5 Suffix tree of Figure 4 augmented with suffix pointers

Observation 1 If the suffix tree for any string

S has a branch node that represents the string

Y, then the tree also has a branch node that represents the longest proper suffix

Z of

Y.

Proof Let

P be the branch node for

Y. Since

P is a branch node, there are at least

2 different digits

x and

y such that

S has a suffix that begins with

Yx and another that begins with

Yy. Therefore,

S has a suffix that begins with

Zx and another that begins with

Zy. Consequently, the suffix tree for

S must have a branch node for

Z.

Observation 2 If the suffix tree for any string

S has a branch node that represents the string

Y, then the tree also has a branch node for each of the suffixes of

Y.

Proof Follows from Observation 1.

Note that the suffix tree of Figure 5 has a branch node for

pe. Therefore, it also must have branch nodes for the suffixes

e and

epsilon of

pe.

The concepts of the last branch node and the last branch index are useful in describing the suffix tree construction algorithm. The last branch node for suffix

suffix(i) is the parent of the information node that represents

suffix(i). In Figure 5, the last branch nodes for suffixes

1 through

6 are

C, B, B, C, B, and

A, respectively. For any suffix

suffix(i), the last branch index

lastBranchIndex(i) is the index of the digit on which a branch is made at the last branch node for

suffix(i). In Figure 5,

lastBranchIndex(1) = 3 because

suffix(1) = peeper;

suffix(1) is represented by information node

H whose parent is node

C; the branch at

C is made using the third digit of

suffix(1); and the third digit of

suffix(1) is

S[3]. You may verify that

lastBranchIndex[1:6] = [3, 3, 4, 6, 6, 6].

Observation 3 In the suffix tree for any string

S,

lastBranchIndex(i) <= lastBranchIndex(i+1),

1 <= i < n.

Proof Left as an exercise.

Get Out That Hammer and Saw, and Start Building

To build your very own suffix tree, you must start with your very own string. We shall use the string

R = ababbabbaabbabb to illustrate the construction procedure. Since the last digit

b of

R appears more than once, we append a new digit

# to

R and build the suffix tree for

S = R# = ababbabbaabbabb#. With an

n = 16 digit string

S, you can imagine that this is going to be a rather long example. However, when you are done with this example, you will know everything you ever wanted to know about suffix tree construction.

Construction Strategy

The suffix tree construction algorithm starts with a root node that represents the empty string. This node is a branch node. At any time during the suffix tree construction process, exactly one of the branch nodes of the suffix tree will be designated the active node. This is the node from where the process to insert the next suffix begins. Let

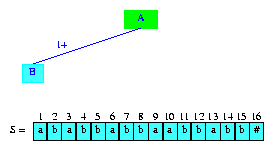

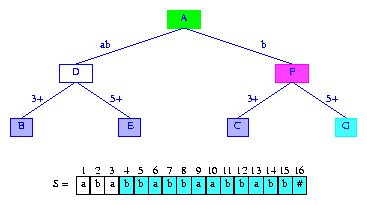

activeLength be the length of the string represented by the active node. Initially, the root is the active node and activeLength = 0. Figure 6 shows the initial configuration, the active node is shown in green.

Figure 6 Initial configuration for suffix tree construction

As we proceed, we shall add branch and information nodes to our tree. Newly added branch nodes will be colored magenta, and newly added information nodes will be colored cyan. Suffix pointers will be shown in red.

Suffixes are inserted into the tree in the order

suffix(1), suffix(2), ..., suffix(n). The insertion of the suffixes in this order is accomplished by scanning the string S from left to right. Let tree(i) be the compressed trie for the suffixes suffix(1), ..., suffix(i), and let lastBranchIndex(j, i) be the last branch index for suffix(j) in tree(i). Let minDistance be a lower bound on the distance (measured by number of digits) from the active node to the last branch index of the suffix that is to be inserted. Initially, minDistance = 0 as lastBranchIndex(1,1) = 1. When inserting suffix(i), it will be the case that lastBranchIndex(i,i) >= i + activeLength + minDistance. To insert

suffix(i+1) into tree(i), we must do the following:

- Determine

lastBranchIndex(i+1, i+1). To do this, we begin at the current active node. The firstactiveLengthnumber of digits of the new suffix (i.e., digitsS[i+1], S[i+2], ..., S[i + activeLength]) will be known to agree with the string represented by the active node. So, to determinelastBranchIndex(i+1,i+1), we examinine digitsactiveLength + 1,activeLength + 2, ..., of the new suffix. These digits are used to follow a path throughtree(i)beginning at the active node and terminating whenlastBranchIndex(i+1,i+1)has been determined. Some efficiencies result from knowing thatlastBranchIndex(i+1,i+1) >= i + 1 + activeLength + minDistance. - If

tree(i)does not have a branch nodeXwhich represents the stringS[i]...S[lastBranchIndex(i+1,i+1)-1], then create such a branch nodeX. - Add an information node for

suffix(i+1). This information node is a child of the branch nodeX, and the label on the edge fromXto the new information node isS[lastBranchIndex(i+1, i+1)]...S[n].

Back to the Example

We begin by inserting

suffix(1) into the tree tree(0) that is shown in Figure 6. The root is the active node, activeLength = minDistance = 0. The first digit of suffix(1) is S[1] = a. No edge from the active node (i.e., the root) of tree(0) has a label that begins with a (in fact, at this time, the active node has no edge at all). Therefore, lastBranchIndex(1,1) = 1. So, we create an information node and an edge whose label is the entire string. Figure 7 shows the result, tree(1). The root remains the active node, and activeLength and minDistance are unchanged.

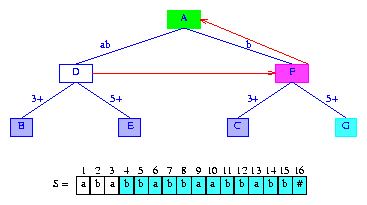

Figure 7 After the insertion of the suffix ababbabbaabbabb#

In our drawings, we shall show the labels on edges that go to information nodes using the notation

i+, where i gives the index, in S, where the label starts and the + tells us that the label goes to the end of the string. Therefore, in Figure 7, the edge label 1+ denotes the string S[1]...S[n]. Figure 7 also shows the string S. The newly inserted suffix is shown in cyan. To insert the next suffix,

suffix(2), we again begin at the active node examining digits activeLength + 1 = 1, activeLength + 2 = 2, ..., of the new suffix. Since, digit 1 of the new suffix is S[2] = b and since the active node has no edge whose label begins with S[2] = b, lastBranchIndex(2,2) = 2. Therefore, we create a new information node and an edge whose label is 2+. Figure 8 shows the resulting tree. Once again, the root remains the active node and activeLength and minDistance are unchanged.

Figure 8 After the insertion of the suffix babbabbaabbabb#

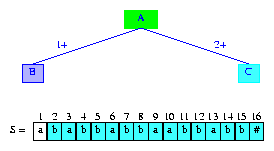

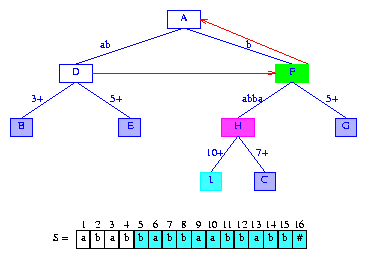

Notice that the tree of Figure 8 is the compressed trie

tree(2) for suffix(1) and suffix(2). The next suffix,

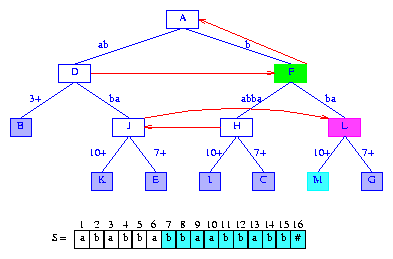

suffix(3), begins at S[3] = a. Since the active node of tree(2) (i.e., the root) has an edge whose label begins with a, lastBranchIndex(3,3) > 3. To determine lastBranchIndex(3,3), we must see more digits of suffix(3). In particular, we need to see as many additional digits as are needed to distinguish between suffix(1) and suffix(3). We first compare the second digit S[4] = b of the new suffix and the second digit S[2] = b of the edge label 1+. Since S[4] = S[2], we must do additional comparisons. The next comparison is between the third digit S[5] = b of the new suffix and the third digit S[3] = a of the edge label 1+. Since these digits are different, lastBranchIndex(3,3) is determined to be 5. At this time, we update minDistance to have the value 2. Notice that, at this time, this is the max value possible for minDistance because lastBranchIndex(3,3) = 5 = 3 + activeLength + minDistance. To insert the new suffix,

suffix(3), we split the edge of tree(2) whose label is 1+ into two. The first split edge has the label 1,2 and the label for the second split edge is 3+. In between the two split edges, we place a branch node. Additionally, we introduce an information node for the newly inserted suffix. Figure 9 shows the tree tree(3) that results. The edge label 1,2 is shown as the digits S[1]S[2] = ab.

Figure 9 After the insertion of the suffix abbabbaabbabb#

The compressed trie

tree(3) is incomplete because we have yet to put in the longest proper suffix pointer for the newly created branch node D. The longest suffix for this branch node is b, but the branch node for b does not exist. No need to panic, this branch node will be the next branch node created by us. The next suffix to insert is

suffix(4). This suffix is the longest proper suffix of the most recently inserted suffix, suffix(3). The insertion process for the new suffix begins by updating the active node by following the suffix pointer in the current active node. Since the root has no suffix pointer, the active node is not updated. Therefore, activeLength is unchanged also. However, we must update minDistance to ensure lastBranchIndex(4,4) >= 4 + activeLength + minDistance. It is easy to see that lastBranchIndex(i,i) <= lastBranchIndex(i+1,i+1) for all i < n. Therefore, lastBranchIndex(i+1,i+1) >= lastBranchIndex(i,i) >= i + activeLength + minDistance. To ensure lastBranchIndex(i+1,i+1) >= i + 1 + activeLength + minDistance, we must reduce minDistance by 1. Since

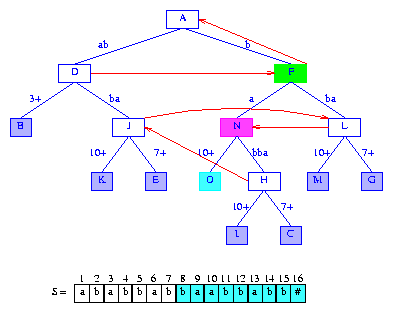

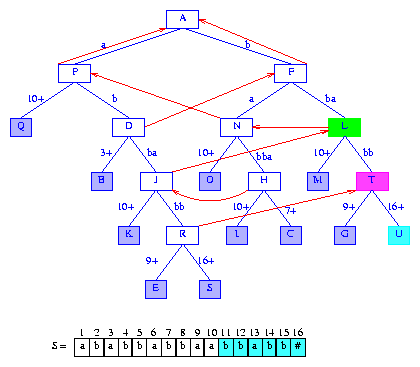

minDistance = 1, we start at the active node (which is still the root) and move forward following the path dictated by S[4]S[5].... We do not compare the first minDistance digits as we follow this path, because a match is assured until we get to the point where digit minDistance + 1 (i.e., S[5]) of the new suffix is to be compared. Since the active node edge label that begins with S[4] = b is more than one digit long, we compare S[5] and the second digit S[3] = a of this edge's label. Since the two digits are different, the edge is split in the same way we split the edge with label 1+. The first split edge has the label 2,2 = b, and the label on the second split edge is 3+; in between the two split edges, we place a new branch node F, a new information node G is created for the newly inserted suffix, this information node is connected to the branch node F by an edge whose label is 5+. Figure 10 shows the resulting structure.

Figure 10 After the insertion of the suffix bbabbaabbabb#

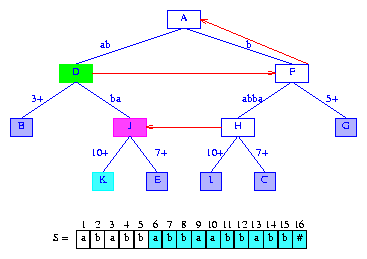

We can now set the suffix pointer from the branch node

D that was created when suffix(3) was inserted. This suffix pointer has to go to the newly created branch node F. The longest proper suffix of the string

b represented by node F is the empty string. So, the suffix pointer in node F is to point to the root node. Figure 11 shows the compressed trie with suffix pointers added. This trie is tree(4).

Figure 11 Trie of Figure 10 with suffix pointers added

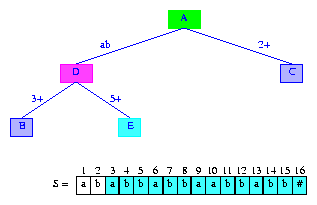

The construction of the suffix tree continues with an attempt to insert the next suffix

suffix(5). Since suffix(5) is the longest proper suffix of the most recently inserted suffix suffix(4), we begin by following the suffix pointer in the active node. However, the active node is presently the root and it has no suffix pointer. So, the active node is unchanged. To preserve the desired relationship among lastBranchIndex, activeLength, minDistance, and the index (5) of the next suffix that is to be inserted, we must reduce minDistance by one. So, minDistance becomes zero. Since

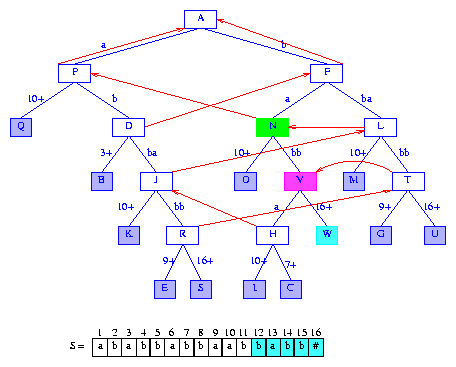

activeLength = 0, we need to examine digits of suffix(5) beginning with the first one S[5]. The active node has an edge whose label begins with S[5] = b. We follow the edge with label b comparing suffix digits and label digits. Since all digits agree, we reach node F. Node F becomes the active node (whenever we encounter a branch node during suffix digit examination, the active node is updated to this encountered branch node) and activeLength = 1. We continue the comparison of suffix digits using an edge from the current active node. Since the next suffix digit to compare is S[6] = a, we use an active node edge whose label begins with a (in case such an edge does not exist, lastBranchIndex for the new suffix is activeLength + 1). This edge has the label 3+. The digit comparisons terminate inside this label when digit S[10] = a of the new suffix is compared with digit S[7] = b of the edge label 3+. Therefore, lastBranchIndex(5,5) = 10. minDistance is set to its max possible value, which is lastBranchIndex(5,5) - (index of suffix to be inserted) - activeLength = 10 - 5 - 1 = 4. To insert

suffix(5), we split the edge (F,C) that is between nodes F and C. The split takes place at digit splitDigit = 5 of the label of edge (F,C). Figure 12 shows the resulting tree.

Figure 12 After the insertion of the suffix babbaabbabb#

Next, we insert

suffix(6). Since this suffix is the longest proper suffix of the last suffix suffix(5) that we inserted, we begin by following the suffix link in the active node. This gets us to the tree root, which becomes the new active node. activeLength becomes 0. Notice that when we follow a suffix pointer, activeLength reduces by 1; the value of minDistance does not change because lastBranchIndex(6,6) >= lastBranchIndex(5,5). Therefore, we still have the desired relationship lastBranchIndex(6,6) >= 6 + activeLength + minDistance. From the new active node, we follow the edge whose label begins with

a. When an edge is followed, we do not compare suffix and label digits. Since minDistance = 4, we are assured that the first mismatch will occur five or more digits from here. Since the label ab that begins with a is 2 digits long, we skip over S[6] and S[7] of the suffix, move to node D, make D the active node, update activeLength to be 2 and minDistance to be 2, and examine the label on the active node edge that begins with S[8] = b. The label on this edge is 5+. We omit the comparisons with the first two digits of this label because minDistance = 2 and immediately compare the fifth digit S[10] = a of suffix(6) with the third digit S[7] = b of the edge label. Since these are different, the edge is split at its third digit. The new branch node that results from the edge split is the node that the suffix pointer of node H of Figure 12 is to point to. Figure 13 shows the tree that results.

Figure 13 After the insertion of the suffix abbaabbabb#

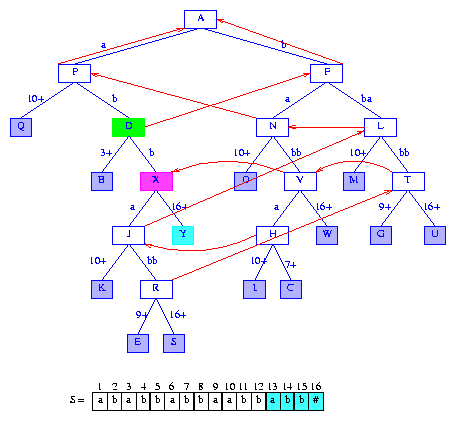

Notice that following the last insertion, the active node is

D, activeLength = 2, and minDistance = 2. Next, we insert

suffix(7). Since this suffix is the longest proper suffix of the suffix just inserted, we can use a short cut to do the insertion. The short cut is to follow the suffix pointer in the current active node D. By following this short cut, we skip over a number of digits that is 1 less than activeLength. In our example, we skip over 2 - 1 = 1 digit of suffix(7). The short cut guarantees a match between the skipped over digits and the string represented by the node that is moved to. Node F becomes the new active node and activeLength is reduced by 1. Once again, minDistance is unchanged. (You may verify that whenever a short cut is taken, leaving minDistance unchanged satisfies the desired relationship among lastBranchIndex, activeLength, minDistance, and the index of the next suffix that is to be inserted.) To insert

suffix(7), we use S[8] = b (recall that because of the short cut we have taken to node F, we must skip over activeLength = 1 digit of the suffix) to determine the edge whose label is to be examined. This gets us the label 5+. Again, since minDistance = 2, we are assured that digits S[8] and S[9] of the suffix match with the first two digits of the edge label 5+. Since there is a mismatch at the third digit of the edge label, the edge is split at the third digit of its label. The suffix pointer of node J is to point to the branch node that is placed between the two parts of the edge just split. Figure 14 shows the result.

Figure 14 After the insertion of the suffix bbaabbabb#

Notice that following the last insertion, the active node is

F, activeLength = 1, and minDistance = 2. If lastBranchIndex(7,7) had turned out to be greater than 10, we would increase minDistance to lastBranchIndex(7,7) - 7 - activeLength. To insert

suffix(8), we first take the short cut from the current active node F to the root. The root becomes the new active node, activeLength is reduced by 1 and minDistance is unchanged. We start the insert process at the new active node. Since minDistance = 2, we have to move at least 3 digits down from the active node. The active node edge whose label begins with S[8] = b has the label b. Since minDistance = 2, we must follow edge labels until we have skipped 2 digits. Consequently, we move to node F. Node F becomes the active node, minDistance is reduced by the length 1 of the label on the edge (A,F) and becomes 1, activeLength is increased by the length of the label on the edge (A,F) and becomes 1, and we follow the edge (F,H) whose label begins with S[9] = a. This edge is to be split at the second digit of its edge label. The suffix pointer of L is to point to the branch node that will be inserted between the two edges created when edge (F,H) is split. Figure 15 shows the result.

Figure 15 After the insertion of the suffix baabbabb#

The next suffix to insert is

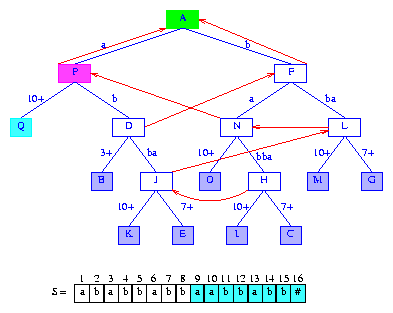

suffix(9). From the active node F, we follow the suffix pointer to node A, which becomes the new active node. activeLength is reduced by 1 to zero, and minDistance is unchanged at 1. The active node edge whose label begins with S[9] = a has the label ab. Since minDistance = 1, we compare the second digit of suffix(9) and the second digit of the edge label. Since these two digits are different, the edge (A,D) is split at the second digit of its label. Further the suffix pointer of the branch node M that was created when the last suffix was inserted into the trie, is to point to the branch node that will be placed between nodes A and D. Finally, since the newly created branch node represents a string whose length is one, its suffix pointer is to point to the root. Figure 16 shows the result.

Figure 16 After the insertion of the suffix aabbabb#

As you can see, creating a suffix trie can be quite tiring. Let's continue though, we have, so far, inserted only the first

9 suffixes into our suffix tree. For the next suffix,

suffix(10), we begin with the root A as the active node. We would normally follow the suffix pointer in the active node to get to the new active node from which the insert process is to start. However, the root has no suffix pointer. Instead, we reduce minDistance by one. The new value of minDistance is zero. The insertion process begins by examining the active node edge (if any) whose label begins with the first digit

S[10] = a of suffix(10). Since the active node has an edge whose label begins with a, additional digits are examined to determine lastBranchIndex(10,10). We follow a search path from the active node. This path is determined by the digits of suffix(10). Following this path, we reach node J. By examining the label on the edge (J,E), we determine that lastBranchIndex(10,10) = 16. Node J becomes the active node, activeLength = 4, and minDistance = 2. When

suffix[10] is inserted, the edge (J,E) splits. The split is at the third digit of this edge's label. Figure 17 shows the tree after the new suffix is inserted.

Figure 17 After the insertion of the suffix abbabb#

To insert the next suffix,

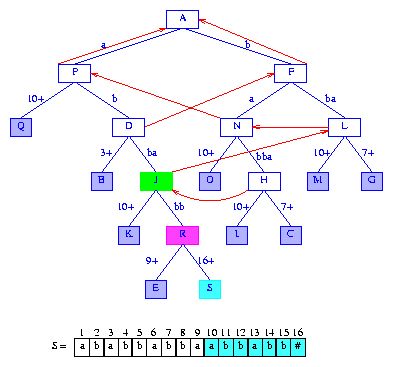

suffix(11), we first take a short cut by following the suffix pointer at the active node. This pointer gets us to node L, which becomes the new active node. At this time, activeLength is reduced by one and becomes 3. Next, we need to move forward from L by a number of digits greater than minDistance = 2. Since digit activeLength + 1 of suffix(11) is S[14] = b we follow the b edge of L. We omit comparing the first minDistance digits of this edge's label. The first comparison made is between S[16] = # (digit of suffix) and S[7 + 2] = a (digit of edge label). Since these two digits are different, edge (L,G) is to be split. Splitting this edge (at its third digit) and setting the suffix pointer from the most recently created branch node R gives us the tree of Figure 18.

Figure 18 After the insertion of the suffix bbabb#

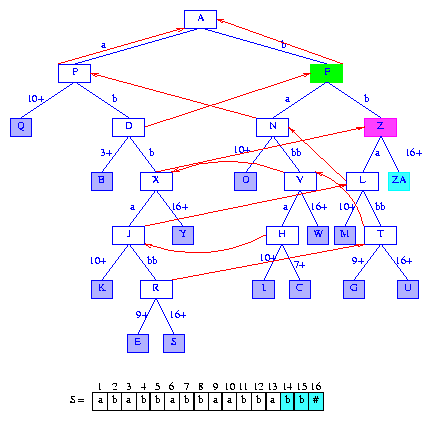

To insert the next suffix,

suffix(12), we first take the short cut from the current active node L to the node N. Node N becomes the new active node, and we begin comparing minDistance + 1 = 3 digits down from node N. Edge (N,H) is split. Figure 19 shows the tree after this edge has been split and after the suffix pointer from the most recently created branch node T has been set.

Figure 19 After the insertion of the suffix babb#

When inserting

suffix(13), we follow the short cut from the active node N to the branch node P. Node P becomes the active node and we are to move down the tree by at least minDistance + 1 = 3 digits. The active node edge whose label begins with S[14] = b is used first. We reach node D, which becomes the active node, and minDistance becomes 1. At node D, we use the edge whose label begins with S[15] = b. Since the label on this edge is two digits long, and since the second digit of this label differs from S[16], this edge is to split. Figure 20 shows the tree after the edge is split and the suffix pointer from node V is set.

Figure 20 After the insertion of the suffix abb#

To insert

suffix(14), we take the short cut from the current active node D to the branch node F. Node F becomes the active node. From node F, we must move down by at least minDistance + 1 = 2 digits. We use the edge whose label begins with S[15] = b (S[15] is used because it is activeLength = 1 digits from the start of suffix(14)). The split takes place at the second digit of edge (F,L)'s label. Figure 21 shows the new tree.

Figure 21 After the insertion of the suffix bb#

The next suffix to insert begins at

S[15] = b. We take the short cut from the current active node F, to the root. The root is made the current active node and then we move down by minDistance + 1 = 2 digits. We follow the active node edge whose label begins with b and reach node F. A new information node is added to F. The suffix pointer for the last branch node Z is set to point to the current active node F, and the root becomes the new active node. Figure 22 shows the new tree.

Figure 22 After the insertion of the suffix b#

Don't despair, only one suffix remains. Since no suffix is a proper prefix of another suffix, we are assured that the root has no edge whose label begins with the last digit of the string

S. We simply insert an information node as a child of the root. The label for the edge to this new information node is the last digit of the string. Figure 23 shows the complete suffix tree for the string S = ababbabbaabbabb#. The suffix pointers are not shown as they are no longer needed; the space occupied by these pointers may be freed.

Figure 23 Suffix tree for ababbabbaabbabb#

Complexity Analysis

Let

r denote the number of different digits in the string S whose suffix tree is to be built (r is the alphabet size), and let n be the number of digits (and hence the number of suffixes) of the string S. To insert

suffix(i), we

- (a)

- Follow a suffix pointer in the active node (unless the active node is the root).

- (b)

-

Then move down the existing suffix tree until

minDistancedigits have been crossed. - (c)

-

Then compare some number of suffix digits with edge label digits until

lastBranchIndex(i,i)is determined. - (d)

- Finally insert a new information node and possibly also a branch node.

n inserts) is O(n). When moving down the suffix tree in part (b), no digit comparisons are made. Each move to a branch node at the next level takes

O(1) time. Also, each such move reduces the value of minDistance by at least one. Since minDistance is zero initially and never becomes less than zero, the total time spent in part (b) is O(n + total amount by which minDistance is increased over all n inserts). In part (c),

O(1) time is spent determining whether lastBranchIndex(i,i) = i + activeLength + minDistance. This is the case iff minDistance = 0 or the digit x at position activeLength + minDistance + 1 of suffix(i) is not the same as the digit in position minDistance + 1 of the label on the appropriate edge of the active node. When lastBranchIndex(i,i) != i + activeLength + minDistance, lastBranchIndex(i,i) > i + activeLength + minDistance and the value of lastBranchIndex(i,i) is determined by making a sequence of comparisons between suffix digits and edge label digits (possibly involving moves downwards to new branch nodes). For each such comparison that is made, minDistance is increased by 1. This is the only circumstance under which minDistance increases in the algorithm. So, the total time spent in part (c) is O(n + total amount by which minDistance is increased over all n inserts). Since each unit increase in the value of minDistance is the result of an equal compare between a digit at a new position (i.e., a position from which such a compare has not been made previously) of the string S and an edge label digit, the total amount by which minDistance is increased over all n inserts is O(n). Part (d) takes

O(r) time per insert, because we need to initialize the O(r) fields of the branch node that may be created. The total time for part (d) is, therefore, O(nr). So, the total time taken to build the suffix tree is

O(nr). Under the assumption that the alphabet size r is constant, the complexity of our suffix tree generation algorithm becomes O(n). The use of branch nodes with as many children fields as the alphabet size is recommended only when the alphabet size is small. When the alphabet size is large (and it may be as large as

n, making the above algorithm an O(n2) algorithm), the use of a hash table results in an expected time complexity of O(n). The space complexity changes from O(nr) to O(n). A divide-and-conquer algorithm that has a time and space complexity of

O(n) (even when the alphabet size is O(n)) is developed in Optimal suffix tree construction with large alphabets. Exercises

- Draw the suffix tree for

S = ababab#. - Draw the suffix tree for

S = aaaaaa#. - Draw the multiple string suffix tree for

S1 = abba, S2 = bbbb,ands3 = aaaa. - Prove Observation 3.

- Draw the trees

tree(i), 1 < = i < = |S|forS = bbbbaaaabbabbaa#. Show the active node in each tree. Also, show the longest proper suffix pointers. - Draw the trees

tree(i), 1 < = i < = |S|forS = aaaaaaaaaaaa#. Show the active node in each tree. Also, show the longest proper suffix pointers. - Develop the class

SuffixTree. Your class should include a method to create the suffix tree for a given string as well as a method to search a suffix tree for a given pattern. Test the correctness of your methods. - Explain how you can obtain the multiple string suffix tree for

S1, ..., Skfrom that forS1, ..., S(k-1). What is the time complexity of your proposed method?

References and Selected Readings

You can learn more about the genome project and genomic applications of pattern matching from the following Web sites:

- NIH's Web site for the human genome project

- Department of Energy's Web site for the human genomics project

- Biocomputing Hypertext Coursebook.

Linear time algorithms to search for a single pattern in a given string can be found in most algorithm's texts. See, for example, the texts:

- Computer Algorithms, by E. Horowitz, S. Sahni, and S. Rajasekeran, Computer Science Press, New York, 1998.

- Introduction to Algorithms, by T. Cormen, C. Leiserson, and R. Rivest, McGraw-Hill Book Company, New York, 1992.

For more on suffix tree construction, see the papers:

- ``A space economical suffix tree construction algorithm,'' by E. McCreight, Journal of the ACM, 23, 2, 1976, 262-272.

- ``On-line construction of suffix trees,'' by E. Ukkonen, Algorithmica, 14, 3, 1995, 249-260.

- Fast string searching with suffix trees,'' by M. Nelson, Dr. Dobb's Journal, August 1996.

- Optimal suffix tree construction with large alphabets, by M. Farach, IEEE Symposium on the Foundations of Computer Science, 1997.

You can download C++ code to construct a suffix tree from http://www.ddj.com/ftp/1996/1996.08/suffix.zip. This code, developed by M. Nelson, is described in paper 3 above.