Inheritance versus composition

One of the fundamental activities of an object-oriented design is establishing relationships between classes. Two fundamental ways to relate classes are inheritance and composition. Although the compiler and Java virtual machine (JVM) will do a lot of work for you when you use inheritance, you can also get at the functionality of inheritance when you use composition. This article will compare these two approaches to relating classes and will provide guidelines on their use.

First, some background on the meaning of inheritance and composition.

About inheritance In this article, I'll be talking about single inheritance through class extension, as in:

class Fruit {

//...

}

class Apple extends Fruit {

//...

}

In this simple example, class Apple is related to class Fruit by inheritance, because Apple extends Fruit. In this example,Frui tis the super class and Apple is the subclass.

I won't be talking about multiple inheritance of interfaces through interface extension. That topic I'll save for next month's Design Techniques article, which will be focused on designing with interfaces.

Here's a UML diagram showing the inheritance relationship between Apple and Fruit:

Figure 1. The inheritance relationship

About composition By composition, I simply mean using instance variables that are references to other objects. For example:

class Fruit {

//...

}

class Apple {

private Fruit fruit = new Fruit();

//...

}

In the example above, class Apple is related to class Fruit by composition, because Apple has an instance variable that holds a reference to a Fruito bject. In this example,Apple is what I will call the front-end class and Fruit is what I will call the back-end class. In a composition relationship, the front-end class holds a reference in one of its instance variables to a back-end class.

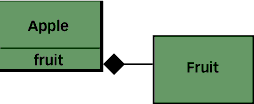

The UML diagram showing the composition relationship has a darkened diamond, as in:

Figure 2. The composition relationship

Dynamic binding, polymorphism, and change

When you establish an inheritance relationship between two classes, you get to take advantage of dynamic binding and polymorphism. Dynamic binding means the JVM will decide at runtime which method implementation to invoke based on the class of the object. Polymorphism means you can use a variable of a superclass type to hold a reference to an object whose class is the superclass or any of its subclasses.

One of the prime benefits of dynamic binding and polymorphism is that they can help make code easier to change. If you have a fragment of code that uses a variable of a superclass type, such asFruit, you could later create a brand new subclass, such asBanana, and the old code fragment will work without change with instances of the new subclass. IfBananaoverrides any ofFruit's methods that are invoked by the code fragment, dynamic binding will ensure thatBanana's implementation of those methods gets executed. This will be true even though classBananadidn't exist when the code fragment was written and compiled.

Thus, inheritance helps make code easier to change if the needed change involves adding a new subclass. This, however, is not the only kind of change you may need to make.

Changing the superclass interface

In an inheritance relationship, superclasses are often said to be "fragile," because one little change to a superclass can ripple out and require changes in many other places in the application's code. To be more specific, what is actually fragile about a superclass is its interface. If the superclass is well-designed, with a clean separation of interface and implementation in the object-oriented style, any changes to the superclass's implementation shouldn't ripple at all. Changes to the superclass's interface, however, can ripple out and break any code that uses the superclass or any of its subclasses. What's more, a change in the superclass interface can break the code that defines any of its subclasses.

For example, if you change the return type of a public method in classFruit(a part ofFruit's interface), you can break the code that invokes that method on any reference of typeFruitor any subclass ofFruit. In addition, you break the code that defines any subclass ofFruitthat overrides the method. Such subclasses won't compile until you go and change the return value of the overridden method to match the changed method in superclassFruit.

Inheritance is also sometimes said to provide "weak encapsulation," because if you have code that directly uses a subclass, such asApple, that code can be broken by changes to a superclass, such asFruit. One of the ways to look at inheritance is that it allows subclass code to reuse superclass code. For example, ifAppledoesn't override a method defined in its superclassFruit,Appleis in a sense reusingFruit's implementation of the method. ButAppleonly "weakly encapsulates" theFruitcode it is reusing, because changes toFruit's interface can break code that directly usesApple.

The composition alternative

Given that the inheritance relationship makes it hard to change the interface of a superclass, it is worth looking at an alternative approach provided by composition. It turns out that when your goal is code reuse, composition provides an approach that yields easier-to-change code.

Code reuse via inheritance For an illustration of how inheritance compares to composition in the code reuse department, consider this very simple example:

class Fruit {

// Return int number of pieces of peel that // resulted from the peeling activity.

public int peel() {

System.out.println("Peeling is appealing.");

return 1;

}

}

class Apple extends Fruit { }

class Example1 {

public static void main(String[] args) {

Apple apple = new Apple(); int pieces = apple.peel();

}

}

When you run theExample1application, it will print out"Peeling is appealing.", becauseAppleinherits (reuses)Fruit's implementation ofpeel(). If at some point in the future, however, you wish to change the return value ofpeel()to typePeel, you will break the code forExample1. Your change toFruitbreaksExample1's code even thoughExample1usesAppledirectly and never explicitly mentionsFruit.

Here's what that would look like:

class Peel {

private int peelCount;

public Peel(int peelCount) {

this.peelCount = peelCount;

}

public int getPeelCount() {

return peelCount;

} //...

}

class Fruit {

// Return a Peel object that // results from the peeling activity.

public Peel peel() {

System.out.println("Peeling is appealing.");

return new Peel(1);

}

}

// Apple still compiles and works fine

class Apple extends Fruit { }

// This old implementation of Example1 // is broken and won't compile.

class Example1 {

public static void main(String[] args) {

Apple apple = new Apple(); int pieces = apple.peel();

}

}

Code reuse via composition Composition provides an alternative way forAppleto reuseFruit's implementation ofpeel(). Instead of extendingFruit,Applecan hold a reference to aFruitinstance and define its ownpeel()method that simply invokespeel()on theFruit. Here's the code:

class Fruit {

// Return int number of pieces of peel that // resulted from the peeling activity.

public int peel() {

System.out.println("Peeling is appealing.");

return 1;

}

}

class Apple {

private Fruit fruit = new Fruit();

public int peel() {

return fruit.peel();

}

}

class Example2 {

public static void main(String[] args) {

Apple apple = new Apple();

int pieces = apple.peel();

}

}

In the composition approach, the subclass becomes the "front-end class," and the superclass becomes the "back-end class." With inheritance, a subclass automatically inherits an implemenation of any non-private superclass method that it doesn't override. With composition, by contrast, the front-end class must explicitly invoke a corresponding method in the back-end class from its own implementation of the method. This explicit call is sometimes called "forwarding" or "delegating" the method invocation to the back-end object.

The composition approach to code reuse provides stronger encapsulation than inheritance, because a change to a back-end class needn't break any code that relies only on the front-end class. For example, changing the return type ofFruit'speel()method from the previous example doesn't force a change inApple's interface and therefore needn't breakExample2's code.

Here's how the changed code would look:

class Peel {

private int peelCount;

public Peel(int peelCount) { this.peelCount = peelCount; }

public int getPeelCount() {

return peelCount;

}

//...

}

class Fruit {

// Return int number of pieces of peel that // resulted from the peeling activity.

public Peel peel() {

System.out.println("Peeling is appealing.");

return new Peel(1);

}

}

// Apple must be changed to accomodate // the change to Fruit

class Apple {

private Fruit fruit = new Fruit();

public int peel() {

Peel peel = fruit.peel();

return peel.getPeelCount();

}

}

// This old implementation of Example2 // still works fine.

class Example1 {

public static void main(String[] args) {

Apple apple = new Apple();

int pieces = apple.peel();

}

}

This example illustrates that the ripple effect caused by changing a back-end class stops (or at least can stop) at the front-end class. AlthoughApple'speel()method had to be updated to accommodate the change toFruit,Example2required no changes.

Comparing composition and inheritance

So how exactly do composition and inheritance compare? Here are several points of comparison:

-

It is easier to change the interface of a back-end class (composition) than a superclass (inheritance). As the previous example illustrated, a change to the interface of a back-end class necessitates a change to the front-end class implementation, but not necessarily the front-end interface. Code that depends only on the front-end interface still works, so long as the front-end interface remains the same. By contrast, a change to a superclass's interface can not only ripple down the inheritance hierarchy to subclasses, but can also ripple out to code that uses just the subclass's interface.

-

It is easier to change the interface of a front-end class (composition) than a subclass (inheritance). Just as superclasses can be fragile, subclasses can be rigid. You can't just change a subclass's interface without making sure the subclass's new interface is compatible with that of its supertypes. For example, you can't add to a subclass a method with the same signature but a different return type as a method inherited from a superclass. Composition, on the other hand, allows you to change the interface of a front-end class without affecting back-end classes.

-

Composition allows you to delay the creation of back-end objects until (and unless) they are needed, as well as changing the back-end objects dynamically throughout the lifetime of the front-end object. With inheritance, you get the image of the superclass in your subclass object image as soon as the subclass is created, and it remains part of the subclass object throughout the lifetime of the subclass.

-

It is easier to add new subclasses (inheritance) than it is to add new front-end classes (composition), because inheritance comes with polymorphism. If you have a bit of code that relies only on a superclass interface, that code can work with a new subclass without change. This is not true of composition, unless you use composition with interfaces. Used together, composition and interfaces make a very powerful design tool. I'll talk about this approach in next month's Design Techniques article.

-

The explicit method-invocation forwarding (or delegation) approach of composition will often have a performance cost as compared to inheritance's single invocation of an inherited superclass method implementation. I say "often" here because the performance really depends on many factors, including how the JVM optimizes the program as it executes it.

- With both composition and inheritance, changing the implementation (not the interface) of any class is easy. The ripple effect of implementation changes remain inside the same class.

Choosing between composition and inheritance

So how do all these comparisons between composition and inheritance help you in your designs? Here are a few guidelines that reflect how I tend to select between composition and inheritance.

Make sure inheritance models the is-a relationship My main guiding philosophy is that inheritance should be used only when a subclass is-a superclass. In the example above, anApplelikely is-aFruit, so I would be inclined to use inheritance.

An important question to ask yourself when you think you have an is-a relationship is whether that is-a relationship will be constant throughout the lifetime of the application and, with luck, the lifecycle of the code. For example, you might think that anEmployeeis-aPerson, when reallyEmployeerepresents a role that aPersonplays part of the time. What if the person becomes unemployed? What if the person is both anEmployeeand aSupervisor? Such impermanent is-a relationships should usually be modelled with composition.

Don't use inheritance just to get code reuse If all you really want is to reuse code and there is no is-a relationship in sight, use composition.Don't use inheritance just to get at polymorphism If all you really want is polymorphism, but there is no natural is-a relationship, use composition with interfaces. I'll be talking about this subject next month.

Next month

In next month's Design Techniques article, I'll talk about designing with interfaces.

A request for reader participation

I encourage your comments, criticisms, suggestions, flames -- all kinds of feedback -- about the material presented in this column. If you disagree with something, or have something to add, please let me know.

You can either participate in a discussion forum devoted to this material, enter a comment via the form at the bottom of the article, or e-mail me directly using the link provided in my bio below.

Bill Venners has been writing software professionally for 12 years. Based in Silicon Valley, he provides software consulting and training services under the name Artima Software Company. Over the years he has developed software for the consumer electronics, education, semiconductor, and life insurance industries. He has programmed in many languages on many platforms: assembly language on various microprocessors, C on Unix, C++ on Windows, Java on the Web. He is author of the book: Inside the Java Virtual Machine, published by McGraw-Hill.Learn more about this topic

- Bill Venners' next book is Flexible Java http://www.artima.com/flexiblejava/index.html

- Bill Venners just got back from his European bike trip. Read about it at

http://www.artima.com/bv/travel/bike98.html - The discussion forum devoted to the material presented in this article http://www.artima.com/flexiblejava/fjf/compoinh/index.html

- Links to all previous design techniques articles http://www.artima.com/designtechniques/index.html

- A tutorial on cloning http://www.artima.com/innerjava/cloning.html

- Recommended books on Java design, including information by the Gamma, et al., Design Patterns book http://www.artima.com/designtechniques/booklist.html

- A transcript of an e-mail debate between Bill Venners, Mark Johnson (JavaWorld's JavaBeans columnist), and Mark Balbe on whether or not all objects should be made into beans http://www.artima.com/flexiblejava/comments/beandebate.html

- Source packet that contains the example code used in this article http://www.artima.com/flexiblejava/code.html

- Object orientation FAQ http://www.cyberdyne-object-sys.com/oofaq2/

- 7237 Links on Object Orientation http://www.rhein-neckar.de/~cetus/software.html

- The Object-Oriented Page http://www.well.com/user/ritchie/oo.html

- Collection of information on OO approach http://arkhp1.kek.jp:80/managers/computing/activities/OO_CollectInfor/OO_CollectInfo.html

- Design Patterns Home Page http://hillside.net/patterns/patterns.html

- A Comparison of OOA and OOD Methods http://www.iconcomp.com/papers/comp/comp_1.html

- Object-Oriented Analysis and Design MethodsA Comparative Review http://wwwis.cs.utwente.nl:8080/dmrg/OODOC/oodoc/oo.html

- Patterns discussion FAQ http://gee.cs.oswego.edu/dl/pd-FAQ/pd-FAQ.html

- Patterns in Java AWT http://mordor.cs.hut.fi/tik-76.278/group6/awtpat.html

- Software Technology's Design Patterns Page http://www.sw-technologies.com/dpattern/

- Previous Design Techniques articles http://www.javaworld.com/topicalindex/jw-ti-techniques.html