Use Case Modelling

Capturing user requirements

Introduction

In this chapter we will be looking at Use Case modelling. Use Cases are a critical technique in developing an application. Within the UML Use Cases are used primarily to capture the high level user-functional requirements of a system. This long winded description is important because Use Cases cannot usefully be used to capture non-functional requirements. Nor can they usefully be used to capture "internal" functional requirements. Attempting either or both is a sure path to disaster for two reasons. Firstly because Use Cases are an informal and imprecise modelling technique. But then they were never intended to be anything else. Secondly because the other use that we make of Use Cases is to define the fundamental structure of our application. The Use Case is not only important as a unit of requirement definition but also as our unit of estimation and our unit of work.

This chapter explores the Use Case in more detail and also answers a number of practical questions like - "but what if we need to model user interface and data details ?"

Why do we develop the Use Case model ?

The very first question to be answered then is why do we develop the Use Case model - what Use Cases are and also - very importantly - what they are not.

The Use Case model is about describing WHAT our system will do at a high-level and with a user focus for the purpose of scoping the project and giving the application some structure. Phew ! The Use Cases are the unit of estimation and also the smallest unit of delivery. Each increment that is planned and delivered is described in terms of the Use Cases that will be delivered in that increment.

Use Cases are not a functional decomposition model. Use Cases are not intended to capture all of the system requirements. Use Cases do not capture HOW the system will do anything - nor do they capture anything the actor does that does not involve the system. All of these things are better modelled using other modelling techniques that were developed for those purposes. The Object Model to capture the static structure of the system and the composition of the classes. Object Sequence Diagrams and State Transition Diagrams to capture the detailed dynamic behaviour of the system - the HOW. The Business Process Model to capture the overall business processes - both computerised and manual.

Use Cases are not an inherently object-oriented modelling technique. There is no fundamental reason why they couldn't be used as the front-end to a structured development method - but they're not because the methods gurus are concentrating on the development of OO methods.

How Do We Develop the Use Case Model ?

The first thing to remember when doing Use Case (or any other type of modelling) is WHY are we using this technique. Forgetting that is a sure recipe for disaster. HOW is - relatively speaking - of secondary importance - forget why you're doing use case modelling, the most common mistake in Use Case modelling, and you'll fail. Which is why I will keep repeating this point. If you've forgotten why then go back and re-read the section above. Go on, off you go, I'll wait for you.

A Simple Use Case Recipe

Step 1. Identify the who is going to be using the system directly - e.g. hitting keys on the keyboard. These are the Actors.

Step 2 . Pick one of those Actors.

Step 3. Define what that Actor wants to do with the system. Each of these things that the actor wants to do with the system become a Use Case.

Step 4. For each of those Use Cases decide on the most usual course when that Actor is using the system. What normally happens. This is the basic course.

Step 5. Describe that basic course in the description for the use case.

Describe it as "Actor does something, system does something. Actor does something, system does something." but keep it at a high level. Do not mention any GUI specifics for example. Also you only describe things that the system does that the actor would be aware of and conversely you only describe what the actor does that the system would be aware of.

Do not worry about the alternate paths (extends) or common courses (uses) ! Yet.

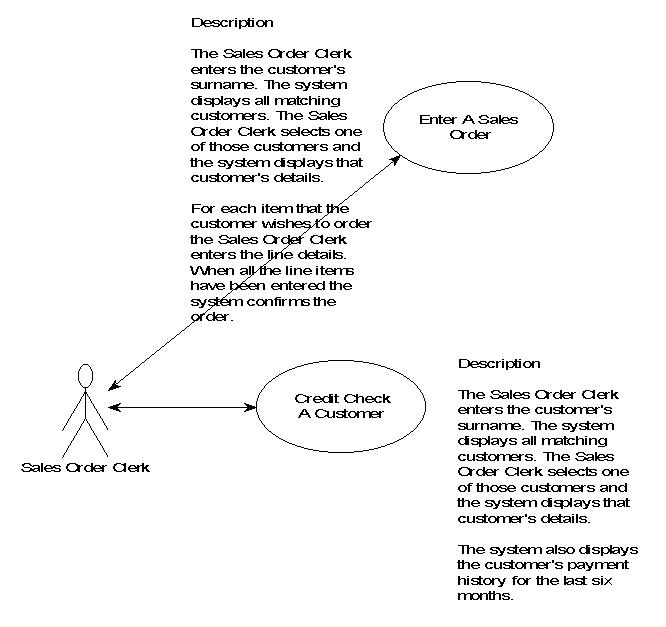

Figure 2 - Describe the Basic Course for each Use Case

Step 6. Once you're happy with the basic course now consider the alternates and add those as extending use cases.

Step 7. Review each Use Case descriptions against the descriptions of the other Use Cases. Notice any glaring commonality ? Extract those out as your common course (used) Use Cases. Note that this is the only valid way of finding "used" Use Cases.

The used, common course, Use Cases are actually the least important of the Use Cases to find. You would have a complete Use Case model even if you did no analysis of the Uses Cases to find these common courses. This is important to remember. Of course if you did not extract these common courses then you would not identify any commonality.

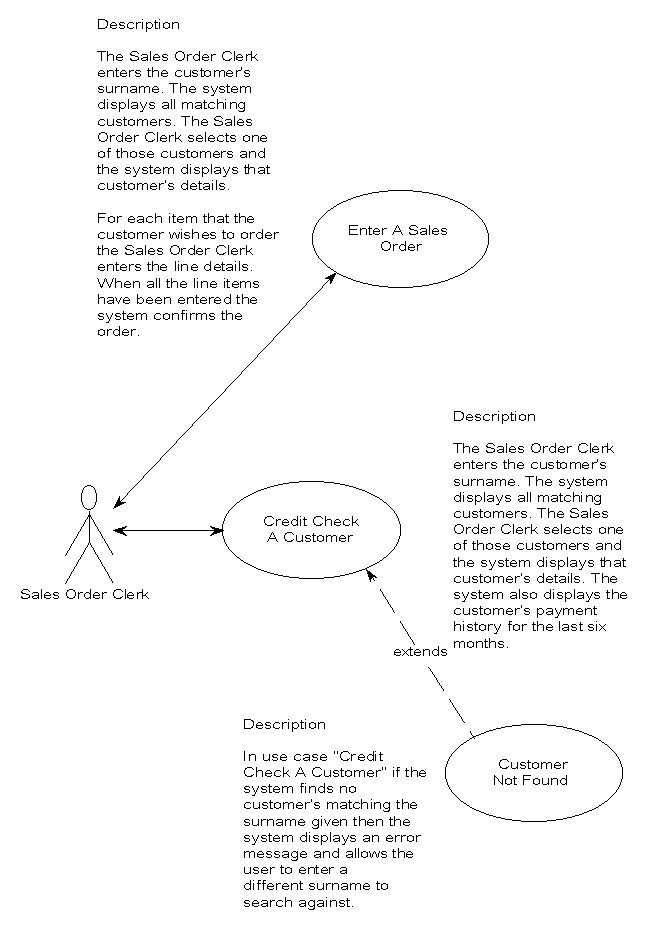

(Note "Customer Not Found" now extends "Display Customer Details").

Step 8. Repeat steps 2 - 7 for each Actor.

Ok so this cook book recipe is a good way of getting started with Use Case modelling. Once you've got started and are comfortable with this process the next step is to begin to understand the trade-offs that can be made. Simplicity versus "completeness" for example. The first thing we'll cover is, perhaps surprisingly, what not to put in. The reason that's being covered next is because putting too much in is the most common mistake. Very rarely - if ever - have I seen too little modelled in a Use Case model.

What Not To Put In

Whilst developing the use case model you my have some more formal or detailed information that you need to capture. Do not put it into the Use Cases ! Instead do a bit of the appropriate type of modelling. If you need to capture a particular relationship between objects, for example the fact that a Sales Order contains one or more Sales Order Lines or that a Customer has an address or that a Customer has a name then capture that on a class diagram. If you need to capture the fact that the Actor selects an address from a list on a GUI dialog then capture that either in an Object Sequence Diagram or in some GUI prototypes or both if appropriate. Do not try to capture this in the Use Cases - there are better ways and you'll have to model it that way anyway so why repeat yourself.

Also be careful about how far you decompose the Use Case model into "used" and "extending" Use Cases. Only decompose as far as is useful in achieving the aims of Use Case modelling: capturing the high-level user functional requirements for the purpose of scoping the project and serving as the basic unit of estimation and deliverable. If you're decomposing down to the nth degree then you're probably just decomposing for its own sake - and that is not good.

Trade Offs

The main trade off in Use Case modelling is between greater completeness (in terms of expression of alternate and common courses) and a simpler model that doesn't express these alternate or common courses.

You may choose during the initial development of the use case model to hold off on the extraction of common and alternate courses because you decide that that is the appropriate level for you to go to in producing a first cut scoping and estimate for the project.

The rule to, carefully, apply is "if it's not useful to model it then don't". This is not an excuse to skimp on modelling. The partner to this rule is "if it is useful then you must model it." But remember you do not model everything in the Use Case model - there are other modelling techniques !

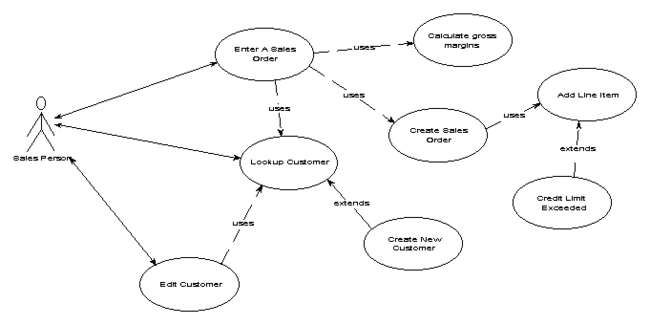

A Case Study In Classic Faults

What we're going to do now is look at a Use Case model that contains the most common mistakes that people make in Use Case modelling. Have a look at the Use Case model pictured below and see if you can spot them. Then read-on and we'll discuss each of them and, most importantly, why they are mistakes and what would be the consequences.

Remember the purpose of Use Case modelling is to capture high-level user-centric requirements for the purpose of scoping the project and giving it some structure. Each Use Case is a unit of estimation and the smallest unit of deliverable.

My initial reaction to this Use Case diagram is that it is very complicated. There are a lot of Use Cases and they have been de-composed to a great degree. It is possible that on closer inspection that it may turn out to be correct - but that is unlikely. The first step then is to question the level of breakdown. Are each of the Use Cases really relevant to the user ? Are they useful as part of the initial estimation process ? Or have they simply been decomposed into smaller and smaller Use Cases just because they could be ? Have the "uses" and "extends" relationships been used correctly ? The consequence of developing a system based on a Use Case model like this would be firstly that the Use Cases are too small to be able to make useful estimates against. Secondly the structure of the application becomes "bitty" and you will see that most clearly in the Object Sequence Diagrams which end up being simply collections of probes to other Object Sequence Diagrams. (See the Class Mistakes section of the OSD chapter for more on this).

Let's examine those "Uses" relationships first. Misapplications of the "uses" relationships generally fall into one of two categories. And we have examples of both of those here. They both are a result of forgetting that "uses" is purely about expressing commonality in the use cases, or to put it simply that one or more use cases share the same piece of descriptive text and that this is not just co-incidence.

Looking at.the "used" Use Cases "Calculate Gross Margins", "Create Sales Order" and "Add Line Item" the first question to ask is given that "uses" is about expressing commonality - where is it ? These three Use Cases are each only "used" by a single Use Case. For this to be valid then "Calculate Gross Margins" and the others would each have to be "used" by at least two Use Cases - otherwise where is the commonality ? This is an example of using the "uses" relationship to model functional decomposition - and that is not what Use Cases are for. That will be modelled at the Object Sequence Diagram (OSD) level.

If we now turn to the Use Case "Lookup Customer" - which is both referenced directly by an actor and is "used" by two other Use Cases: "Enter A Sales Order" and "Edit Customer". This is another one of those "it might be valid but it's unlikely constructs". Where a single Use Case is both a primary Use Case - i.e. one used directly by an Actor - and is "used" by, in this case, two other Use Cases. Just by looking at the structure of the Use Case model it may not seem obvious why. It does however become more obvious when we look at the Use Case descriptions. For the moment we'll ignore any errors in the description itself as we're going to be looking at that later.

Use Case: Enter A Sales Order

The actor selects a customer from a list displayed by the system. Use use case "Lookup Customer". The system then displays the sales order screen and the actor enters the item code and quantity required for each item. The system displays a running total of the value of the order. Once the order is complete the actor confirms the order and the systems resets ready for the next order.

Use Case: Lookup Customer

The actor selects a customer by entering their reference number. The system then displays the complete details of that customer, name, address etc along with a complete history of purchases they have made.

And then read the "Enter A Sales Order" in the way that they would be run. This is the effective basic course of the Use Case "Enter A Sales Order".

The actor selects a customer from a list displayed by the system. The actor selects a customer by entering their reference number. The system then displays the complete details of that customer, name, address etc along with a complete history of purchases they have made. The system then displays the sales order screen and the actor enters the item code and quantity required for each item. The system displays a running total of the value of the order. Once the order is complete the actor confirms the order and the systems resets ready for the next order.

This is a very simple example but you can see the problem straight away: we repeat the same task - of identifying the customer - twice and differently in each case ! Firstly by picking from a list and then again by entering a customer id. We've also picked up some other baggage that we may (or may not) have wanted - to do with displaying the customer's complete sales history. You might want to do that if you were going in to primarily look up a customer's details - but when entering a sales order ? And every time ? The problem here - as with most problems associated with the mis-use of the "uses" relationship is that it has been decomposed without reference to the Use Case descriptions - when that should be precisely the driving factor.

Now let's look at the extends. Both of these are basically correct. Only one minor mistake has been made and that is that the name of an extending Use Case is - unlike any other Use Case - the name of the condition under which it runs. So "Credit Limit Exceeded" is a good extending Use Case name but "Create New Customer" should really be named "Customer Not Found" or something similar.

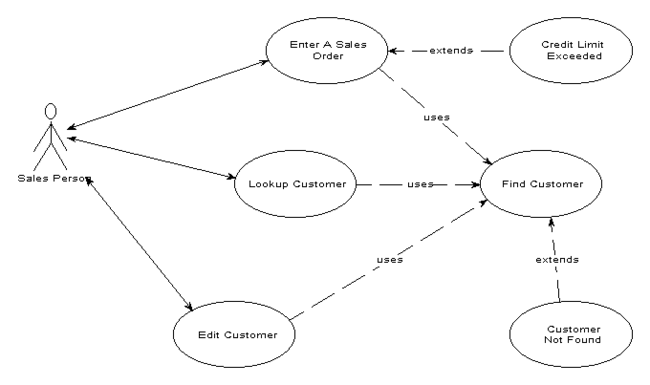

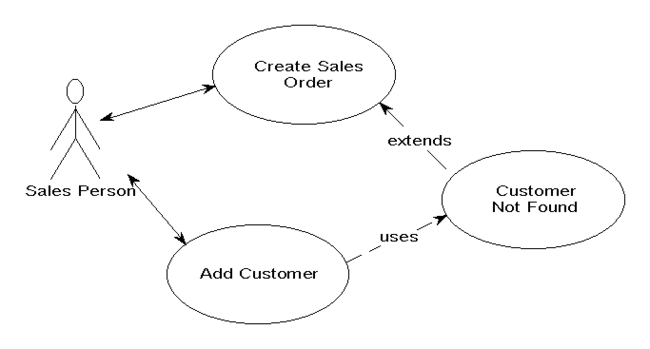

Once we have corrected these mistakes our Use Case model looks like this:

Although in fact I would be more inclined to err on the side of simplicity:

You'll notice that it is much simpler. You'll also notice that all the Use Cases are at a level that makes sense to the user - they are WHAT the system will do - not how. For that reason they're also a much more sensible unit for our estimation and unit of deliverable. What user is going to care that you've delivered the "calculate gross margins" functionality other than as part of a larger piece of more meaningful - to the user - functionality.

A possible concern about making this change is that we have lost information. That is true - we have. But what we have done is made sure that the Use Case model only contains information at an appropriate level. This is important because the Use Case makes the structure of our Use Case is going to drive the rest of our development. Given that then where and how do we capture some of this detail - like that fact that "calculate gross margins" is a common function. The answer is "in the Object Sequence Diagram for that Use Case". If you're doing Use Case modelling and need to model something that shouldn't go in the Use Case diagram then simply switch to the appropriate modelling technique !

The final classic example of a mistake in the structure of a Use Case is shown below.

Figure 8

In this case - because we have correctly named our extending use case as such - i.e. it is named for the condition under which it is run - it's quite obvious that we have made a mistake. Extending use cases contain a conditional clause - by definition they are not and can never be part of the basic course. However a used use case is always part of the basic course (assuming the using Use Case is) because it is unconditional. If the using Use Case is run then normally as part of the basic course so are any used Use Cases. That means that an "extending" - conditional Use Case - can never also be a "used" - unconditional Use Case. (An extending Use Case can however "use" another Use Case. That would be valid but questionable as to whether that level of decomposition was actually useful).

The reason it was done of course is because in adding a new customer we do many of the same things that we do when we discover a customer is not found - we go and create one. To express that commonality we might choose to create a new Use Case "Create New Customer" that is used by both "Add Customer" and "Customer Not Found" and contains precisely what those two Use Cases have in common. Or you may choose not to deciding that the added complexity doesn't really help you. A trade off.

Let's now look at the descriptions behind some of these Use Cases.

Use Case: Enter A Sales Order

The actor selects a customer from a list displayed by the system. The system then displays the sales order screen and the actor enters the item code and quantity required for each item. The system displays a running total of the value of the order. Once the order is complete the actor confirms the order and the systems resets ready for the next order.

We really want to avoid making commitments too early. Here we already made a commitment about how a user is going to select a particular customer: from a list. But what happens when we get into the class modelling and prototyping of the system and discover that there are upwards of 10,000 customers ? A list box would not be appropriate and we've made more work for ourselves - in the form of change management. Avoid detail that commits you to a particular design too early.

Let's look at another possible version of this same Use Case's description.

Use Case: Enter A Sales Order

- Display list of customers from central database.

- Actor chooses one of those customers.

- The system displays sales order form.

- While there are more items for this order

actor enters item and quantity

system updates running total - End While

- Confirm the Order

Here the problem is with the style of the description. Use Cases are to describe the user's view of what the system should do. This format is not very user friendly - it's more like high-level pseudo code (what we would expect in an OSD) than a Use Case description. The format of the description should be more prosaic - written as an exchange between the Actor and the system. "The actor does something, the system does something. The actor does something else in response to that and the system responds." It can include jargon where appropriate - but user - business domain - jargon, not implementation jargon. A better version of that Use Case description would be:

Use Case: Enter A Sales Order

The sales person selects a customer. The system prompts the salesperson to enter the details of the order (item code and quantity) and maintains a running total of the value of the order. Once the salesperson is happy with the order they confirm it and the system records the confirmed order.

User friendly, and without making any commitment about how we are going to provide this functionality - just that we are.

Conclusion

Remember: Use Cases are about capturing HIGH-LEVEL, USER-CENTRIC requirements for the purpose of scoping the project. Use Case modelling should, must, be a short stage in the project's life cycle. Forgetting this is the surest way to disastrous Use Case models.

Bibliography and Further Reading

"Object Oriented Software Engineering: A Use Case Driven Approach" by Ivar Jacobsen.

UML Reference