Visual Cryptography

Visual Cryptography

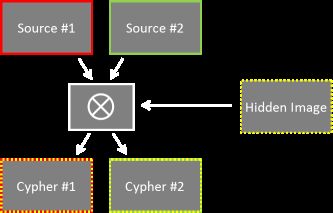

The technique I’m going to describe is attributed to two great mathematicians: Moni Naor and Adi Shamir, in 1994. In this implementation, I'm going to show how to split a secret message into two components. Both parts are necessary to reconstruct and reveal the secret, and the possession of either one, alone, is useless in determining the secret.

|

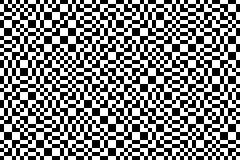

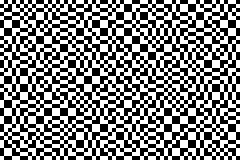

The basis of the technique is the superposition (overlaying) of two semi-transparent layers. Imagine two sheets of transparency covered with a seemingly random collection of black pixels. |

|

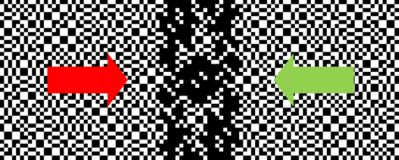

Individually, there is no discernable message printed on either one of the sheets. Overlapping them creates addition interference to the light passing through (mathematically the equivalent of performing a Boolean OR operation with the images), but still it just looks like a random collection of pixels.

|

| Mysteriously, however, if the two grids are overlaid correctly, at just the right position, a message magically appears! The patterns are designed to reveal a message. |

|

Demonstration

Let’s look at couple of examples of this in action, then we’ll describe how the technique works.

Below you will see two random looking rectangles of dots. One is fixed in the center, and the other you can drag around the canvas. As the rectangles intersect, the images merge. If you align the rectangles perfectly, a hidden message will appear. There are three hidden message to see in this demonstration, once you’ve decoded one, click on the square button in the bottom left to advance to the next.

To give you feedback, once the images are perfectly aligned, the advance button will go blank with a red border (don’t worry, your computer will not self-destruct in five seconds)

How does it work?

| First we take a monochrome image for the source. Pixels in the image are either white or black. To the right is the source for the first example we saw above. |

|

We need to distribute the shading such that, if you have just one of the cypher images, it is impossible to determine what is on the other cypher image, and thus, impossible to decrypt the image.

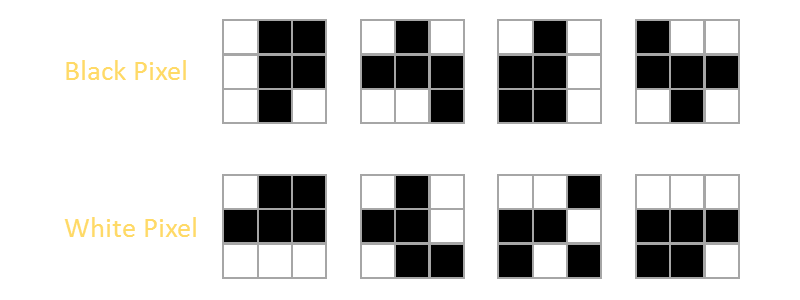

What we do is look at the color of each pixel in the original source image. If the original pixel in the image is set (black), we fill in all four sub pixels then distribute them two per cypher layer. We flip a coin to determine which pattern we place on which layer (so that it is random). It does not matter which pair of pixels goes on which layer, when they are combined, all four pixels will be black.

|

Conversely, if the source image pixel is white, we shade in just two pixels. This time, however, we make sure that the same pixels are shaded on both layers. In this way, when the two cypher images are combined, only two pixels are shaded. As before, we flip a coin to determine which chiral set we go with, and make sure the same image appears on both layers.

Someone who has possession of only one of the cypher images will be able to determine the (2 x 2) pattern of each pixel but has no idea if the corresponding pixel cluster on the other image is the same (white space), or opposite (black pixel). Every grid of (2 x 2) sub pixels on both layers contains exactly two pixels.

Here is a short animation of a some of these (2 x 2) pixel sub-blocks sliding over each other:

Pretty cool, huh? Well hold on, it gets cooler …

Moni Naor, Adi Shamir, and more people …

The original paper by Naor and Shamir talks about how to implement this system in a more generic way. For instance, instead of splitting the image into just two cypher texts, why don't we split the image between n-cyphertexts; all of which are needed to be combined to reveal the final image? (Or possibly a subset of any k images out of these n).

If you are interested in reading more, you can find a reprint of the original paper here.

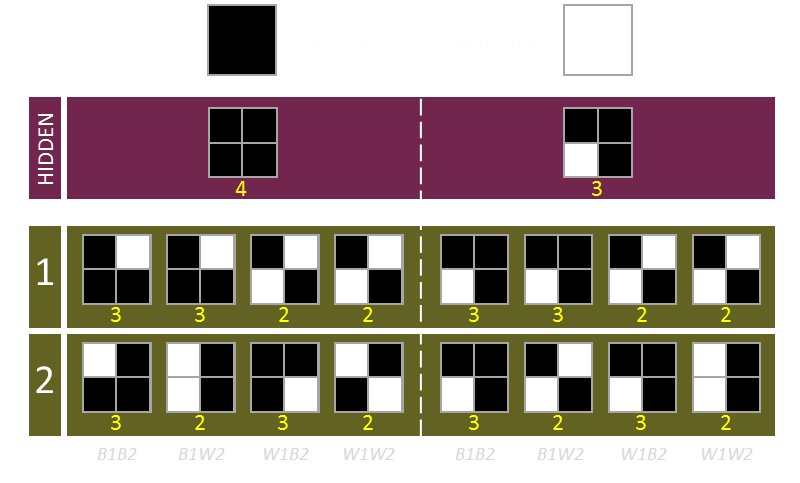

As an example, here are some (3 x 3) sub-elements that could be used to distribute an image over four cypher images, all of which are needed to be combined to reveal the secret images:

The top line shows the subpixels used to represent a black pixel in the original images, and the bottom line a white pixel.

-

Any single share contains exactly five black subpixels.

-

Any stacked pair contains exactly seven black subpixels.

-

Any stacked triplet contains eight black subpixels.

Deeper down the rabbit hole:Visual Steganography

I’ve done this below. Trust me, you’re not going to believe this at first. You’re going to be convinced that there is some ‘behind the scenes’ script at work that changes the image. I assure you this is not the case. You’re still not going to believe me!

Below, on the left, is my name, encoded from a monochrome image, and also containing partial details of a third hidden image. On the right is the word ‘Fish’, similarly encoded. Now, drag the right image over to the left image and watch what happens when they overlap perfectly. Wham! How cool is that?

How does this magic work?

The hidden image we are encoding has black pixels and white pixels. As before, we sub divide each pixel into (2 x 2) subpixels. When the two images are combined, we want to represent the black pixels of the hidden image by having all four subpixels black. We’ll represent the white pixels has having three subpixels black. This is sufficient contrast for the hidden image to be seen.

For each black or white pixel in the hidden image, there are four possible combinations of black and white pixels of the two source images. For the two source images, we’re going to say that any three black subpixels represents black in that source image, and any two pixels represents white.

Examples of all eight permutations of source, image 1 and image 2 are depicted below:

When the hidden image pixel is BLACK:

-

The combined two cypher images (OR) have to have all four subpixels set.

-

When both source images also have a black pixel, this is easy. Both cypher images need to have three out of the four subpixels set. The only constraint is that the missing subpixel is not the same on both layers. One subpixel is randomly selected on the first layer, and one is randomly select from the other three on the second layer.

-

When the first image has a black pixel (requiring three subpixels set), and the second image has a white pixel (requiring two subpixels set), as above, first, a random single subpixel is selected on the black layer to remove. Next two subpixels are randomly selected on the second layer with the constraint that one of the selected subpixels is the same as the gap in the first layer. In this way, when the two are combined, four black subpixels are displayed.

-

The opposite happens when the first layer is white, and the second layer is black.

-

Finally, if both source pixels are white (requiring just two subpixels set), two subpixels are selected at random on the first layer, and the inverse of this selection used for the second layer.

When the hidden image pixel is WHITE:

-

The combined two cypher images (OR) have to have any three subpixels set.

-

When both source images have a black pixel, this is easy. Both cypher images need to have three out of the four subpixels set, and these need to be the same subpixels. Three subpixels are randomly selected and these are set on both of the cypher image layers.

-

When the first image has a black pixel (requiring three subpixels set), and the second image has a white pixel (requiring two subpixels set), as above, first, three random subpixels are selected on the first layer. Next one of these three subpixels is randomly selected for removal and this pattern is used on the second layer.

-

The opposite happens when the first layer is white, and the second layer is black.

-

Finally, if both source pixels are white (requiring two subpixels set), two are selected at random on the first layer, then one of these is duplicated on the second layer, and a second random subpixel is selected on the second layer (from the two white subpixels notselected on the first layer). Both layers have two subpixels, and when combined, there are three subpixels visbile.

Other potential uses of the concept

The ability to give an answer, and potentially mask a true answer to a question, tangentially, reminds me of a technique used to get truthful representations in surveys where the subject is potentially embarrassing or where there is incentive to not give a truthful answer.

Any person looking at the survey results and seeing a ”Yes” on an answer will not know if any single person's answer is truthful, or the result of a coin flip. Any person can be free of embarrassment as none of his/her peers will know either.

Other articles related to this topic

If you liked this article, you might also like this article about Steganography, and this one about Sharing Secrets.

Check out other interesting blog![]() articles here.

articles here.