作者:Peter McGraw / Joel Warner

出版社:Simon & Schuster

副标题:A Global Search for What Makes Things Funny

发行时间:April 1st 2014

来源:下载的 epub 版本

Goodreads:3.41 (677 Ratings)

豆瓣:无

It might seem that there’s no way to cover the wide world of comedy with a single, tidy explanation. But for someone like Pete, a guy who yearns for order, that wouldn’t do. “People say humor is such a complex phenomenon, you can’t possibly have one theory that explains it,” he told me. “But no one talks that way about other emotional experiences. Most scientists agree on a simple set of principles that explain when most emotions arise.” It’s generally accepted that anger occurs when something bad happens to you and you blame someone else for it, while guilt occurs when something bad happens to someone else and you blame yourself.

It has to be the same for humor, Pete figured. There has to be a simple explanation that the authorities have long overlooked. He thinks he found it by doing a Google search for “humor theory.”

One of the first results led to “A Theory of Humor,” an article published in a 1998 issue of HUMOR: The International Journal of Humor Research, written by a man named Thomas Veatch. Veatch posited what he called the “N+V Theory,” the idea that humor occurs when someone perceives a situation is a violation of a “subjective moral principle” (V) while simultaneously realizing that the situation is normal (N). To prove that his idea worked, Veatch, who had a PhD in linguistics from the University of Pennsylvania, laid out point after compelling point, meandering from computational linguistics to developmental psychology to predicate calculus. It’s heady, compelling stuff, and to Pete, Veatch’s theory was closer to the truth than anything he’d come across. But it hadn’t rocked the field of humor scholarship. Why had Veatch and his N+V Theory sunk into obscurity?

While Veatch had once taught linguistics at Stanford University, he’d since dropped off the academic radar. It took several weeks of online sleuthing and unreturned voice mails to get Veatch on the phone from his home in Seattle.

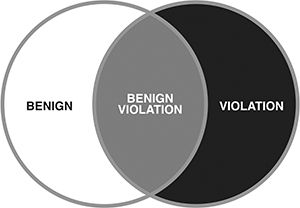

So Pete and Caleb set upon improving Veatch’s work and ended up with a new comedic axiom: the benign violation theory. According to this amended theory, humor only occurs when something seems wrong, unsettling or threatening (i.e., a violation), but simultaneously seems okay, acceptable, or safe (i.e., benign). When something is just a violation, such as somebody falling down the stairs, people feel bad about it. But according to Pete and Caleb, when the violation turns out to be benign, such as someone falling down the stairs and ending up unhurt, people often do an about-face and react in at least one of three ways: they feel amused, they laugh, or they make a judgment—“That was funny.”

To them, the term “benign,” rather than “normal,” better encapsulated the many ways a violation could be okay, acceptable, or safe—and gave them a clear-cut tool to determine when and why a violation such as the feline-turned-sex-toy story can be funny. While heavy petting with a kitten may not be normal, according to the story, the kitten purred and seemed to enjoy the contact. The violation was benign—no kittens were harmed in the making of the joke. Later, when Pete and Caleb used this story in an experiment, participants who read a version in which the kitten whined in displeasure at the heavy petting found the tale far less funny than the “happy kitty” scenario.

And tickling, long a sticking point for other humor theories, fits perfectly. After all, tickling involves violating someone’s physical space in a benign way. People can’t tickle themselves—a phenomenon that baffled Aristotle—because it isn’t a violation. Nor will people laugh if a creepy stranger tries to tickle them, since nothing about that is benign.

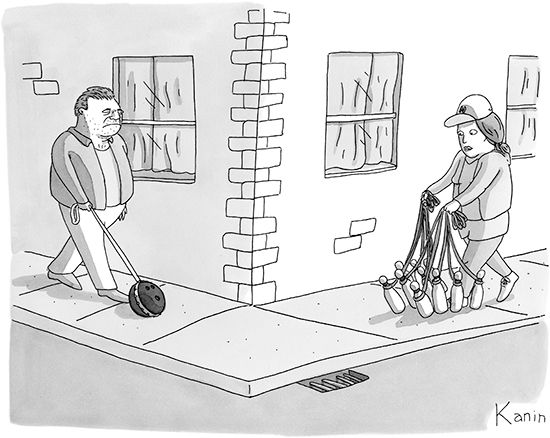

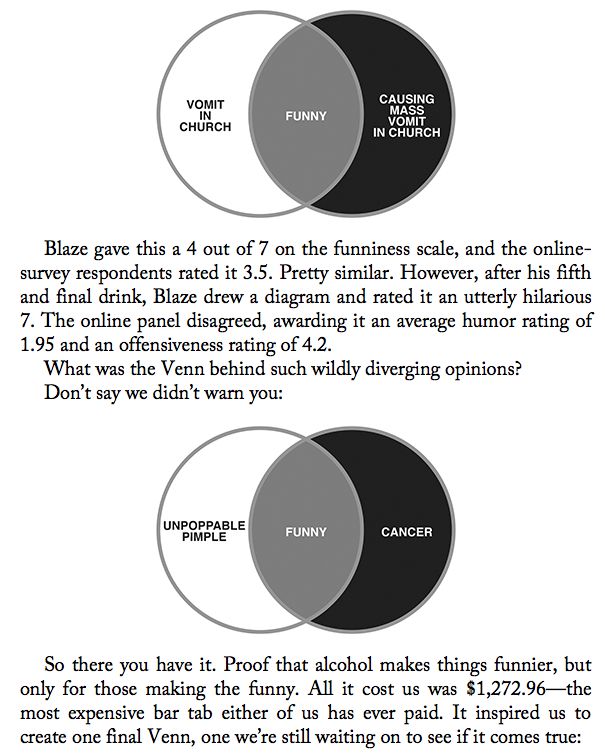

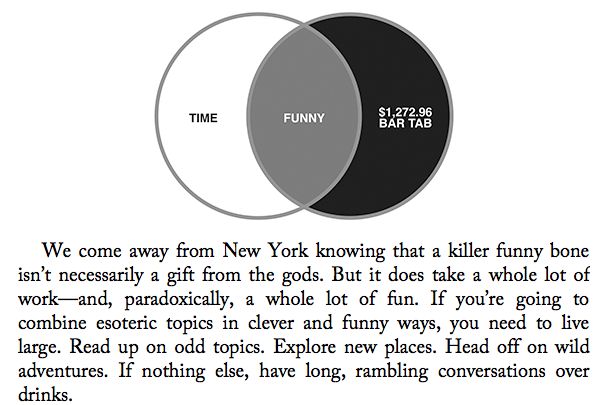

At the Hurricane Club, is all the booze we’re buying turning the ad team into Kanin-level humorists? They believe so. The more drinks they down, the funnier they rate their comedy attempts. But later, when Pete submits the Venns to an online survey panel, he finds the inebriated ad team is off the mark. According to the panel’s respondents, the shenanigans went downhill by the time the ad team reached its fifth drink. Take, for example, one creative director who went by the code name Blaze. After his third drink, Blaze rated himself about halfway up the drunkenness scale and came up with this gem: