作者:Seth Lerer, Ph.D.

版本:Jul 8, 2013, 2nd Edition

出版社:thegreatcourses.com

来源:下载的 PDF 版本

本来以为可以很快翻掉的,没想到内容还蛮精彩的,查一下这个主题的书有好几本,不像国内有豆瓣可以简单的看评分或者书评大致了解一本书的好坏,外语书好坏的参考标准如何评估呢?还不是很清楚。不过有一个网站做了系统的梳理:http://www.thehistoryofenglish.com/

书的内容涵盖了英语的整个发展史:

from its origins as a dialect of Germanic-speaking peoples, through the literary and cultural documents of its 1,500-year span, to the state of American speech of the present day.

通过语言的发展史,去看民族的发展史,确实是非常有意思的角度,目前只看了前9章,诺曼人入侵以后中古英语被迫引入大量法语词汇:出现「教堂的拉丁语,贵族的法语,民众的英语」三语并存,世界上的任何名族都有过悲催的往事~

作者是 University of California, San Diego 的教授:

Seth Lerer joined the Literature Department in January 2009 as Distinguished Professor and as Dean of Arts and Humanities. His teaching and research address Medieval and Renaissance Literature, the History of the English Language, Children’s Literature, and the history of the book. Most recently, he has been working on Shakespeare

作者的一个 TED

《The History of Reading and the Literate Life: Seth Lerer at TEDxUCSD》

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X_Z5HNRC_Ic

摘录:

Anyone who comes to English as a child in school or as an adult who speaks another language is invariably confronted by the strangeness of its spelling. English has many “silent” letters and clusters of consonants or vowels that seem to be mutable, giving us different sounds in different contexts. Why is that the case? English spelling has remained historical and etymological. In other words, English, by and large, preserves older forms of the language by using conservative spelling.

Scholars have three tools for studying language historically: articulatory phonetics, sociolinguistics, and comparative philology.

- Articulatory phonetics is the representation of the sounds of a language using symbols developed for that purpose or the description of sounds according to where and how they are produced in the mouth.

- Sociolinguistics is the study of how language operates in society and brings people into communities of culture. This study also encompasses social attitudes toward language variation, use, and change.

- Comparative philology is the technique of reconstructing earlier forms of a language by comparing surviving forms in recorded languages.

Meaning, or semantics, is at the heart of language. Let’s look at an example of semantic change with the word silly. In Old English and Modern German, the root of this word means blessed, touched by the spirit of the Lord. Over time, the word came to describe, not an inner spiritual condition of someone, but the outer and physical manifestations of silliness. By the 15th and 16th centuries, the word moved from a description of an interior condition to an exterior condition, and in Modern English, it has completely lost its sense of being blessed.

A modern example of this might be found in the “eye dialect” of Mark Twain or other regionalist writers. These writers evoke the sound of a speaker through spelling: sez for says, wanna for want to, gonna for going to. The eye dialect of early writers gives us a window into early pronunciation. When we look at speech sounds, the historical study of language gives us certain rules and conventions of sound change. We can work backward from these conventions to reconstruct the sounds of earlier languages.

Let’s close this lecture by looking at four myths about language.

- The first of these is the myth of universality. There is, as far as we can tell, no universal language—no single living language that is comprehensible to all speakers—and no way to reconstruct a language that would be comprehensible to all speakers. Nor is there any single word or expression that is the same in all living languages. In the language of the Republic of Georgia, mama means father and dada means mama.

- The second myth is that of simplicity. No language is harder or easier for its own speech community to learn. Six-year-olds in every culture have the same relative ability to speak or write their languages. As a corollary, no language was simpler in an earlier form. Languages neither decay nor evolve.

- The third myth is that of teleology: Language change does not move toward a goal. Languages do not evolve from lower to higher forms.

- Finally, there is the myth of gradualism. Languages do not change at a steady rate. The Great Vowel Shift took place in the space of about 150 years, but the history of pronunciation has been relatively stable for the 400 years since the shift ended. Radical semantic change took place during the Renaissance and is taking place now, but semantics has been stable over other periods of time.

Linguists have developed two broad approaches to classifying languages. Genetic classification implies the growth or development from a “root stock” and the branching into language groups or families. Genetic classification looks for shared features of vocabulary, sound, and grammar that enable scholars to reconstruct earlier forms. This is a historical, or diachronic, system of classification. Typological classification means comparing languages for larger systems of organization. For example, do the languages signal meaning in a sentence by means of inflectional endings (a so-called synthetic language, such as Latin), or do they signal meaning by word order patterns (an analytic language, such as Modern English)? In this synchronic system of classification, what matters is not the historical descent but the current features of the languages.

The western languages that descended from Indo-European are so-called centum languages. Centum is the Latin word for 100, and all these languages have a word for that number closely related to centum. (The Germanic languages have the word beginning with h, which is a later sound change.) The eastern languages are so-called satem languages; satem is the Old Persian or Avastan word for 100. The centumsatem distinctions indicate a historical geographical split in Indo-European, as well as a larger sound change.

We can also make some general claims about the Indo-European language. It was a highly inflected language. It had eight noun cases, including the evocative, locative, and instrumental cases. It had six tenses, each of which was signaled with special verb endings. It had grammatical gender for the nouns. It had a special system of distinguishing words by changing the root vowel to indicate changes in tense, location, or aspect.

In linguistics, the term “ablaut” is used to designate this kind of system. This phenomenon descends into the Germanic languages in the form of strong verbs, that is, those that signal change in tense by a shift in the root vowel of the word: drink, drank, drunk; sing, sang, sung; bring, brought. Weak verbs in the Germanic languages simply take a suffix to indicate the past tense: walk, walked; talk, talked.

Pantheon means “all the gods.” Pan means all, but it is also the Indo-European root for five. Look at your hand; I have five fingers. That’s all the fingers on my hand. And so the root for five and the root for all is the same—a fascinating way in which the bodily condition of life generates a verbal condition of description

the language known as Old English can be defined in four ways: geographically—as a language spoken by the Germanic settlers in the British Isles; historically—as a language spoken from the time of the Germanic settlement in the 5th century until the Norman Conquest in 1066; genetically—as a Lowlands branch of the West Germanic group of languages (in other words, it is a branch of the Germanic languages that emerged from languages spoken in what are now Holland, northern Germany, and Denmark); and typologically—as a language with a particular sound system (phonology), grammatical endings (morphology), word order patterns (syntax), and vocabulary (lexis).

Old English is bounded by geography. The earliest inhabitants of the British Isles were a group of Paleolithic peoples who constructed Stonehenge and other stone-circle monuments. However, we have no linguistic, literary, or verbal remnants of their lives. The earliest inhabitants whose language we can reconstruct were Celtic speakers who migrated from Europe sometime in the second half of the 1st millennium B.C. Modern Celtic languages include Irish, or Gaelic; Welsh; Cornish; Manx, the language of the Isle of Man; and Erse, a language of the Scots. The Celtic speakers brought with them an Indo-European pantheon, along with skills in iron working and certain key vocabulary terms.

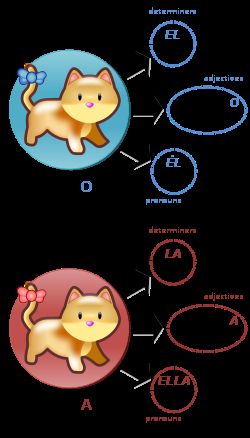

Like all the Germanic languages, Old English had noun declensions. Nouns were in different groups or classes. To signal relationships in a sentence— subject, direct object, indirect object, instrument of action—endings were added to the words. These are known as case endings. All the Indo-European languages had such case endings; we see them, for example, in Latin and Greek and in masculine, feminine, and neuter nouns in many modern European languages. Note that this is grammatical gender, not natural gender. The Old English word for woman, wif, became our modern word wife, but it was a grammatically neuter noun in Old English. All concept nouns (those ending in -ness) were feminine in Old English. The wonderful Old English word witherweardnesse, meaning stress, exhaustion, irritation, is a feminine concept noun

Words from Scandinavian Germanic languages were borrowed after contact with the Vikings and the Danes during their raids on England in the 8th–9th centuries. These words were distinguished by special sounds in the Scandinavian languages, in particular, the sounds sk and k which corresponded to the sounds sh and ch in Old English. Thus, Scandinavian skirt, kirk, skip, and dike have Germanic family cognates in Old English shirt, church, ship, and ditch. Scandinavian languages also had a hard g sound that was not present in Old English; the words muggy, ugly, egg, and rugged are Scandinavian borrowings; certain words with the ll sound, such as ill, were also borrowed. In the 10th and 11th centuries, during the period of the Benedictine Reform, more elaborate and learned Latin words came into Old English, including Antichrist, apostle, canticle, demon, font, nocturne, Sabbath, synagogue, accent, history, paper, and so on

Old English also made new words with distinctive approaches to compounding. Determinative compounding is common to all the Germanic languages and involves forming new words by yoking together two normally In terms of vocabulary, “Caedmon’s Hymn” offers us a lexicon for the divine. 37 independent nouns or a noun and an adjective. Examples of determinative compounding with two nouns include earhring (earring) or bocstæf (bookstaff, meaning “letter”). Examples with an adjective and a noun include middangeard (middle-yard, “Earth”), federhoma (feather coat, “plumage”), and bonlocan (bone locker, “body”). Many of these words make up the unique poetic vocabulary of Old English literature, especially in metaphorical constructions known as kennings. A kenning is a noun metaphor that expresses a familiar object in unfamiliar ways. The sea, for example, could be known as the hronrad, whale road.

Repetitive compounding brings together words that are nearly identical or that complement and reinforce each other for specific effect. Thus, holtwudu meant, essentially, wood-wood, in Old English, or forest; gangelwæfre meant the going-about weaver or the swift-moving one, that is, a spider. Noun-adjective formations constitute another approach to compounding, giving us græsgrene (grass green), lofgeorn (praise-eager, or eager for praise), and goldhroden (gold-adorned). In Modern English, this form of compounding is revived in such phrases as king-emperor or fi ghter-bomber.

Prefix formations were the most common way of creating new words in Old English and other Germanic languages. Old English had many prefixes that derived from prepositions and altered the meanings of words in special ways. For example, the prefix and- meant back or in response to. Thus, one could swear in Old English or andswar, meaning to answer. The prefix with- meant against. One could stand or withstand something in Old English, meaning to stand against.

I’d like to disabuse us of the notion that on some blustery day in the fall of 1066, the English language and English culture irrevocably changed—that one day Anglo-Saxons were a group of pipe-toting, mead-swilling barbarians who overnight were transformed into a group of fops eating champignons in a beurre-blanc sauce.

the year 1066, the date of the Norman Conquest of England, is shrouded in mystery and mythology. What did the Norman Conquest do to English? Did the Normans really conquer the English language? How can we see the effects of this political upheaval on the history of English and in our own study of the language today? In this lecture, we’ll review some of the major effects that the Norman Conquest had on the English language, but we’ll also see that the language was changing long before the conquest and continued to change throughout the British Isles in spite of the influence of the French-speaking Normans.

Let’s begin with some of the natural changes in Old English that took place from its earliest times. Recall that our best evidence for language change is the writing of the barely literate. In several texts from the 10th and 11th centuries, we can see that the complex system of noun case endings was gradually being lost. As mentioned earlier, Old English had an inflectional system, in which special endings were used to distinguish whether a noun was the subject of a sentence, the direct object, the indirect object, the object of possession, or the instrument of an action. The term that describes the falling together of the old system of case endings is “syncretism.” In this process, endings collapse into smaller and smaller groups, until a limited collection of sounds comes to represent a larger set of grammatical categories.

In addition to noun endings, adjective endings (such as those that delineated number or gender) were lost in this period of Old English. Verb endings were maintained, but simplified. Old English, like other Indo-European languages, had a dual pronoun in addition to the singular and plural (I and we). This third pronoun signaled two people, but this distinctive feature of the language was also lost in this period. Grammatical gender disappeared, to be replaced by natural gender. Nouns were no longer masculine, feminine, or neuter.

Why did these changes take place? Some theories have been proposed that hinge on stress, form, and function. Old English, like all Germanic languages, had fixed stress on the root syllable of the word. In other words, regardless of what prefixes or suffixes were added to the word, the stress remained on the root syllable. Examples include come, become; timber, betimber (to build); swerian, answerian (answer). Some scholars believe that this insistent stress tended to level out the sounds of unstressed syllables. Any sound or syllable that did not take the full word stress, such as a grammatical ending, would not have been pronounced clearly.

It’s important to note that the chronicle was not necessarily kept year by year. Instead, our evidence tells us that every 20 years, or 10, or five, a scribe would copy out what had happened in the preceding years. In this way, blocks of text highlight—in gross form—the ways in which the English language was changing during the transitional period right after the Norman Conquest.

Let’s look at the following examples:

| Year | Phrase | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1083 | on pisum geare | The endings “-um” and “-e” signal a dative masculine singular. This is classic Old English. |

| 1117 | on pison geare | The “-um” ending has been replaced with “-on.” The adjectival ending seems to have been replaced with an indiscriminate vowel plus an indiscriminate nasal (“-m” or “-n”). This may be the scribe’s attempt to preserve a grammatical ending or preserve the sound of speech. |

| 1135 | on pis geare | The adjectival ending of this has been lost, but the “-e” at the end of geare still signals a dative. Concord in grammatical gender is obviously gone by this time. |

| 1154 | on pis gear | The endings have completely disappeared. We are no longer in the world of inflected Old English. |

We can trace several other changes in the period after the Norman Conquest. As mentioned earlier, word order patterns were regularized. The order of subject-verb-object became the standard for the simple declarative sentence. Other word order patterns were used for special kinds of expression; for example, in asking a question, the standard word order would be inverted to verb-subject-object: Know I the way? Both Shakespeare and the King James Bible preserve this archaism in asking questions. Other archaisms, such as methinks, meaning it seems to me, survived until the time of the Renaissance.

What the Norman Conquest did in altering the vocabulary structure of English was not simply increase the raw vocabulary—the raw number of words—it changed conceptually or systematically the vernacular in the British Isles. It changed it from one that resisted the acceptance of loan words to one that accepted almost voraciously new loan words.

New words brought into a language can affect word stress. In the Germanic languages and Old English, in particular, word stress was fixed on the root syllable of a word, but this was not true for the Romance languages, including French and Norman French. The idea of variable word stress can be seen in Modern English. For example, the word record (pronounced “reCORD”) is a verb, but record (with the accent on the first syllable) is a noun. Here, different stress patterns on different syllables change the meaning and grammatical function of the word. We see another example in canon (an accepted set of texts, values, or individuals), pronounced “CA-non,” and canonization (the act of making a canon), with the stress on the “a” before “tion.”

French loan words in English are easy to spot:

- Words spelled with ei, ey, or oy: cloy, joy.

- Endings in -ion or -ioun: extension, retention.

- Endings in -ment: emolument, condiment.

- Endings in -ence or -aunce: existence. • Endings in -or or -our: color, honor.

In Central French, words that end in -ous are adjectives; words that end in -us are nouns. Thus, callous is an adjective, while callus is a noun. This spelling convention still works in Modern English

The influence of French is especially apparent in matters of cuisine, itself a French word. Sir Walter Scott noted in his novel Ivanhoe that words for animals are Old English and words for meats are French. We might imagine an Anglo-Saxon peasant raising a cow on his land, but when that cow appeared as meat on a Norman Frenchman’s table, it became boeuf (beef). The same transformation is seen in calf-veal, deer-venison, and sheep-mutton. These kinds of pairings show us how French became the language of high culture, while English remained the language of the land.

Medieval England was a trilingual culture. Latin had become the language of the church, education, and philosophy. French was the language of administration, culture, and courtiership. English was the language of popular expression, regional dialect, and personal reflection. The Harley Lyrics, a collection of literature written probably in the 1330s in Hertfordshire, gives us clear evidence of writers and readers who were, in a broad sense, trilingual. One poem in the manuscript (#2253) ends with this quatrain:

Scripsi hec carmina in tabulis;

Mon ostel es en mi la vile de Paris;

May y sugge namore, so wel me is;

3ef hi de3e for loue of hire, duel hit ys.I have written these verses on my tablets;

My dwelling is in the middle of the city of Paris;

Let me say no more, so things are fine;

But if I die for love of her, it would be a pity

The firstline here is in Latin, the second is in French, and the third and fourth are in Middle English. This poem shows us the brilliance of medieval trilingual culture, to be found in the stratification of languages. An English schoolboy would write on his tablet in the language of learning—Latin. When he went to the university, he would have traveled to Paris and learned French. But when he wanted to express himself and his love, he would have done so in his own Middle English.

概念摘录:

Great Vowel Shift

The Great Vowel Shift was a major series of changes in the pronunciation of the English language that took place in southern England, primarily between 1350 and the 1600s and 1700s, today influencing effectively all dialects of English. Through this vowel shift, all Middle English long vowels changed their pronunciation. English spelling was first becoming standardized in the 15th and 16th centuries, and the Great Vowel Shift is responsible for the fact that English spellings now often strongly deviate in their representation of English pronunciations.

Northumbrian dialect

Northumbrian was a dialect of Old English spoken in the Anglian Kingdom of Northumbria. Together with Mercian, Kentish and West Saxon, it forms one of the sub-categories of Old English devised and employed by modern scholars.

The dialect was spoken from the Humber, now within England, to the Firth of Forth, now within Scotland. During the Viking invasions of the 9th century, Northumbrian came under the influence of the languages of the Viking invaders.

The earliest surviving Old English texts were written in Northumbrian: these are Caedmon's Hymn and Bede's Death Song. Other works, including the bulk of Caedmon's poetry, have been lost. Other examples of this dialect are the Runes on the Ruthwell Cross from the Dream of the Rood. Also in Northumbrian are the 9th-century Leiden Riddle[1] and the mid-10th-century gloss of the Lindisfarne Gospels.

The Canterbury Tales

The Canterbury Tales (Middle English: Tales of Caunterbury) is a collection of 24 stories that runs to over 17,000 lines written in Middle English by Geoffrey Chaucer between 1387–1400. In 1386, Chaucer became Controller of Customs and Justice of Peace and, in 1389, Clerk of the King's work. It was during these years that Chaucer began working on his most famous text, The Canterbury Tales. The tales (mostly written in verse, although some are in prose) are presented as part of a story-telling contest by a group of pilgrims as they travel together on a journey from London to Canterbury to visit the shrine of Saint Thomas Becket at Canterbury Cathedral. The prize for this contest is a free meal at the Tabard Inn at Southwark on their return.

Grammatical gender

In linguistics, grammatical gender is a specific form of noun-class system in which the division of noun classes forms an agreement system with another aspect of the language, such as adjectives, articles, pronouns, or verbs. This system is used in approximately one quarter of the world's languages. In these languages, most or all nouns inherently carry one value of the grammatical category called gender; the values present in a given language (of which there are usually two or three) are called the genders of that language. According to one definition: "Genders are classes of nouns reflected in the behaviour of associated words."

Archaism

In language, an archaism (from the Ancient Greek: ἀρχαϊκός, archaïkós, 'old-fashioned, antiquated', ultimately ἀρχαῖος, archaîos, 'from the beginning, ancient') is the use of a form of speech or writing that is no longer current or that is current only within a few special contexts. Their deliberate use can be subdivided into literary archaisms, which seeks to evoke the style of older speech and writing; and lexical archaisms, the use of words no longer in common use.

Caedmon’s Hymn

Cædmon's Hymn is a short Old English poem originally composed by Cædmon, an illiterate cow-herder who was able to sing in honour of God the Creator, using words that he had never heard before. It was composed between 658 and 680 and is the oldest recorded Old English poem, being composed within living memory of the Christianization of Anglo-Saxon England. It is also one of the oldest surviving samples of Germanic alliterative verse.

Historical imagination

Collingwood is widely noted for The Idea of History (1946), which collated from various sources soon after his death by a student, T. M. Knox. It came to be a major inspiration for philosophy of history in the English-speaking world and is extensively cited, leading to an ironic remark by commentator Louis Mink that Collingwood is coming to be "the best known neglected thinker of our time".

Collingwood thought that history can not be studied in the same way as natural science because the internal thought processes of historical persons can not be perceived with the physical senses, and past historical events can not be directly observed. He suggested that a historian must "reconstruct" history by using "historical imagination" to "re-enact" the thought processes of historical persons based on information and evidence from historical sources.

《柯林烏 (R. G. Collingwood)的歷史哲學》

http://www.chinesetheology.com/ChanHC/Collingwood.htm

Eye dialect

Eye dialect is the use of nonstandard spelling for speech to draw attention to an ironically standard pronunciation. The term was coined by Prof. George P. Krapp to refer to the literary technique of using nonstandard spelling that implies a pronunciation of the given word that is actually standard, such as wimmin for women; the spelling indicates that the character's speech overall is dialectal, foreign, or uneducated. This form of nonstandard spelling differs from others in that a difference in spelling does not indicate a difference in pronunciation of a word. That is, it is dialect to the eye rather than to the ear. It suggests that a character "would use a vulgar pronunciation if there were one" and "is at the level of ignorance where one misspells in this fashion, hence mispronounces as well".

Grimm's law

Grimm's law (also known as the First Germanic Sound Shift or Rask's rule) is a set of statements named after Jacob Grimm describing the inherited Proto-Indo-European (PIE) stop consonants as they developed in Proto-Germanic (the common ancestor of the Germanic branch of the Indo-European family) in the 1st millennium BC. It establishes a set of regular correspondences between early Germanic stops and fricatives and the stop consonants of certain other centum Indo-European languages (Grimm used mostly Latin and Greek for illustration).

术语摘录:

| word | meaning |

|---|---|

| Indo-European | 印欧语系 |

| trilingual | 三语的 |

| Linguistic description | 语言解释 |

| Linguistic prescription | 语言规范 |

| grammatical gender | 语性(阴性 阳性) |

| etymological | 语源学 |

| archaism | 拟古主义 |

| romance languages | 罗曼斯语(由拉丁语演变而成的语言) |

| colonialism | 殖民主义 |

| Anglophone | 以英语为母语的人 |

| consonants | 辅音 |

| alveolar | 牙槽嵴 |

| alveolar sounds | 齿槽音(t d) |

| velar sounds | 舌根音 |

| glottal sounds | 喉音 |

| interdental | 齿间音(the th sound in thin) |

| anatomical | 解剖学 |

| semantics | 语义学 |

| metaphors | 隐喻 |

| teleology | 目的论 |

| casus | 格 |

| ablaut | 元音交替 |

| cognate | 同源的 |

| synonyms | 同义词 |

| alliterative | 头韵的 |

| syncretism | 语形融合 |

| word stress | 重读音 |

| octosyllabic | 八音节的诗 |

单词摘录:

| word | meaning |

|---|---|

| describing | 描述文法 |

| prescribing | 规范文法 |

| coined | 杜撰 |

| vernacular | 方言 |

| flourishes | 繁荣 |

| bequeath | 遗赠 |

| welter | 起伏 |

| soliloquy | 独白 |

| pedagogues | 教员 |

| pedants | 学者 |

| loci | 地点 |

| fulcrum | 支点 |

| lexicons | 词典 |

| isles | 群岛 |

| archaizing | 仿古 |

| Farsi | 波斯 |

| Celtic | 凯尔特 |

| spawned | 孵化 |

| omnivorous | 杂食类的 |

| labial | 唇部的 |

| connote | 意味着 |

| glosses | 注释 |

| millennium | 一千年 |

| provocations | 证明 |

| descendant | 后裔 后代 |

| efflorescence | 全盛期 |

| connotations | 内涵 |

| resonance | 共鸣 |

| cowherd | 牧牛人 |

| upheaval | 剧变 |

the role of the dictionary in describing and prescribing usage; and the ways in which words change meaning, as well as the manner in which English speakers have coined and borrowed new words from other languages.

Old English emerges as the literary vernacular of the Anglo-Saxons and flourishes until the Norman Conquest

Those debates bequeath to us not just larger arguments about language, but the very literary texts we read.

even in the welter of technical detail sometimes necessary to the historical study of English

Finally, we hear Hamlet’s famous soliloquy, written by Shakespeare in the late 16th century

pedagogues and pedants debated whether a standard should be grounded in university education

these debates were played out in the courts, schools, and official loci of royal administration

As we will see in later lectures, the dictionary of Samuel Johnson (1755) became, in many ways, the fulcrum on which previous and subsequent lexicons have balanced.

These existed in the British Isles from the very beginning.

from the need to recreate among an educated, literate elite a form of pronunciation that would replace French as a prestige form of language.

we’ll see the impact this highly formal and archaizing form of English prose had on later 7 writers, especially American writers of the 19th century

as well as modern languages, ranging from Hindi and Farsi in the east to Celtic, Germanic, and Romance languages in the west.

We’ll learn how the Germanic languages spawned English

the fact that English became an omnivorous consumer of new words and new cultures.

Sounds that are produced only with the lips are known as labial sounds.

the word has come to connote the historical and empirical

such as manuals of Latin for schoolroom teaching, glosses, and dictionaries.

a common language spoken by a group of people who lived in the 4th or 3rd millennium B.C. in southeastern Europe

When we look at the surviving Indo-European languages, what we’re looking at are provocations to describe them genetically or to describe them typologically.

The fact that many of the descendant Indo-European languages share a word for yoke also tells us that

Northumbria was the first area of Anglo-Saxon efflorescence

using synonyms to bring together various connotations of a thing or an idea to enrich its resonance.

a cowherd living in Northumbria

How can we see the effects of this political upheaval on the history of English