Influenza

流感

The centenary of the 20th century’s worst catastrophe

20世纪最大灾难一百周年

陈继龙 译

(本文英文版权归《经济学人》所有)

“Spanish flu” probably killed more people than both world wars combined

“西班牙流感”致死的人数可能比两次世界大战死亡人数总和还要多

ON JUNE 29th 1918 Martín Salazar, Spain’s inspector-general of health, stood up in front of the Royal Academy of Medicinein Madrid. He declared, not without embarrassment, that the disease which was ravaging his country was to be found nowhere else in Europe.

1918年6月29日,西班牙卫生总监马丁·萨拉查站在马德里皇家医学院前,不无尴尬地宣称,肆虐该国的这一疾病在欧洲其他地方没有出现。

In fact, that was not true. The illness in question, influenza, had been sowing misery in France and Britain for weeks, and in America for longer, but Salazar did not know this because the governments of those countries, a group then at war with Germany and its allies, had made strenuous efforts to suppress such potentially morale-damaging news. Spain, by contrast, was neutral, and the press had freely reported on the epidemic since the first cases had appeared in the capital in May. Before the summer was out, the disease Spaniards knew as the “Naples Soldier”—after a tune from a popular operetta—had been dubbed the “Spanish illness” abroad, and that, somewhat unfairly, was the name which stuck.

其实,这种说法并不确切。流感这一疾病已经让法国和英国遭受了数周的苦痛,美国时间更长。但是,萨拉查并不知情,因为那些国家的政府当时正与德国及其盟友交战,所以想方设法压制此类可能挫伤士气的新闻。相比之下,西班牙属中立国,自首都5月出现首发病例起,新闻界一直可以自由报道这一流行病。在西班牙人印象中,该病名叫“那不勒斯士兵”,取自某流行轻歌剧里的一首曲子。(译注:第一波流感来袭时,引人注目的音乐剧《遗忘之歌》(The song of forgetting)正在马德里进行首次公演。人们便借用此剧的角色和剧情,将“那不勒斯士兵”作为此次流感的绰号。)但夏天还没结束,它就被外国冠以“西班牙病”之名,这是有点不公平,但这个名字就这样叫开了。

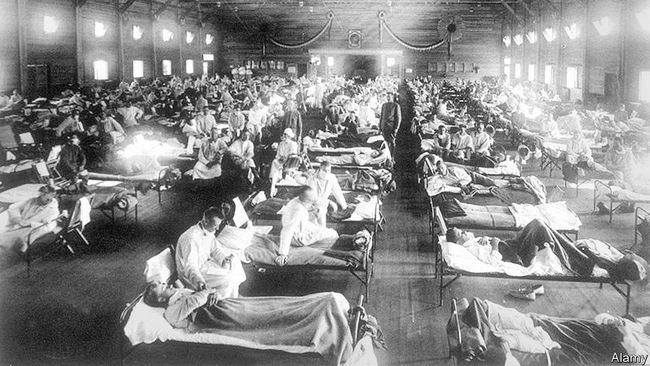

Spanish flu was probably the worst catastrophe of the 20th century. The current estimate is that it killed at least 50m people and perhaps as many as 100m. At minimum, therefore, it ended the lives of three times as many as died in the first world war (in the region of 17m). It was probably also more lethal than the second world war (60m), and may well have outstripped the effects of both wars put together. The death toll was so high partly because Spanish flu was truly pandemic (some 500m people, more than a quarter of those then alive, are believed to have been infected),and partly because of its high mortality rate (5-10%, compared with 0.1% for subsequent influenza epidemics).

西班牙流感可能是20世纪最严重的灾难。据最新估计,它至少导致5000万人死亡,或许多达1亿。所以说,被它夺走的生命起码是第一次世界大战死亡人数(1700万左右)的三倍,也许比第二次世界大战(6000万)更为致命,并且很可能超过两场战争的总致死人数。死亡人数如此之多,一方面是因为西班牙流感流行范围确实非常广(约5亿人,亦即当时总人口数中超过1/4的人都被认为染上此病),再者是由于其具有高致死率(5-10%,而后来的流感仅为0.1%)。

Understanding what happened is therefore important.Two questions in particular need answering. One is: what made this outbreak of influenza so much more lethal than both previous and subsequent ones? The other is: given that knowledge, what defences need to be put in place to nip any similar outbreak in the bud?

因此,弄清发生了什么很重要。有两个问题尤其需要解答:其一,是什么让这场流感的爆发有着如此空前绝后的致命性?其二,有鉴于此,需要采取哪些预防措施,将类似的爆发流行遏止在萌芽状态?

Origin of a species

物种的起源

The first cases of the 1918 flu to be recorded officially as such were at Camp Funston, a military base in Kansas, onMarch 4th 1918. That morning, Albert Gitchell, a mess cook, reported sick. By lunchtime the camp infirmary was dealing with dozens of similar incidents. The highly contagious nature of the Camp Funston outbreak suggests, however, that Gitchell was not the real “patient zero”. An emerging flu strain tends not to infect people very well at first. Researchers hunting for the individual Gitchell caught it from have therefore scoured records for an earlier, more localised outbreak of respiratory disease that quickly petered out.

据官方记载,1918年大流感病例最早于1918年3月4日出现在堪萨斯州一个军事基地——福斯顿军营。当日早晨,食堂炊事员阿尔伯特·吉切尔报告说自己病了。到午饭前,军营医务室处置了数十例类似病情。不过,福斯顿军营爆发的疾病所具有的高传染性表明,吉切尔并不是真正的“零号病人”(首例病人)。新出现的流感病毒往往不会从一开始轻易传染给人。因此,研究人员不再寻找可能把病毒传染给吉切尔的个体,而是从记录中搜索发生时间较早、地点更为明确并且很快烟消云散的呼吸道疾病爆发事件。

At the moment, there are three theories as to where the 1918 flu first manifested itself. John Oxford, a British virologist, has long argued that it was in a British army camp at Étaples on the northern French coast, not far from the Western Front. Here, an outbreak of“purulent bronchitis”, characterised by a dusky blue hue to the face, was reported as early as 1916. Such blue faces were also characteristic of fatal cases of Spanish flu.

关于1918年大流感最早在哪里显现,目前有三种看法。英国病毒学家约翰·奥克斯福特一直坚持认为,这个地方是位于法国北海岸Étaples的一座英国军营,离西线战场不远。有报告显示,这里早在1916年就曾爆发过“化脓性支气管炎”,其特点是面色发青。这种发青的脸部同样也是西班牙流感死亡病例的特征之一。

In 2004 John Barry, an American journalist, put forward a rival theory. He claimed that a small but severe outbreak of flu-like disease in Haskell County, Kansas, in January 1918, could have seeded the later one at Camp Funston. The camp’s catchment area for recruits includedHaskell.

2004年,美国新闻记者约翰·巴里提出了不同的看法。他断言,1918年1月在堪萨斯州哈斯克尔县爆发过一次范围不大但很严重的流感样疾病,可能为后来发生在福斯顿军营的疫情埋下了祸根。这座军营新兵的招募区域就包括哈斯克尔县。

In 2013 a third hypothesis joined these two—or rather was revived, since it was fleetingly popular in the years immediately following the pandemic. According to Mark Humphries, a historian atWilfred Laurier University in Waterloo, Ontario, the 1918 flu began in Shanxi province, China, where an epidemic of severe respiratory disease in December1917 had doctors squabbling over its identity. Some thought it was pneumonic plague, a respiratory variant of bubonic plague to which China was distressingly prone. Others suspected a form of influenza.

2013年,除上述两种看法之外,又出现了第三种假说,或者说得准确些,就是自从大流行过后紧接着的几年里曾经一度广受关注以来,再一次成为热点话题。安大略省滑铁卢市威尔弗瑞德劳里埃大学的历史学家马克·汉弗莱斯认为,1918年大流感始于中国陕西省(或山西省,音同),在那儿,1917年12月发生过一次严重呼吸道疾病的流行,关于具体病种,医生们曾争执不休。有的认为是肺鼠疫,属于腺鼠疫的呼吸道变种,中国比较悲催,容易发生此病;也有的人认为是流感的一种形式。

Since they could not agree, and since it was also difficult to explain how the flu might have travelled from that remote and poorly connected region to the rest of the world, the theory fell by the wayside. Dr Humphries gave it new life when he pointed out that China, though neutral in the war until 1917, nevertheless played a role earlier than this date by providing Allied forces with a body of workers—the Chinese LabourCorps—who were recruited from provinces, including Shanxi, and shipped via Canada to Europe.

由于既无法形成一致意见,又很难解释流感为何会从那个偏僻闭塞的地区传播到世界其他地方,这一理论只能半途而废了。汉弗莱斯博士找到了新的证据。他指出,虽然中国直到1917年在战争中都是中立国,但是早在此前就通过为盟军提供一批劳工即中国劳工营,在战争中扮演了某种角色。这些劳工来自包括陕西在内的多个省份,用船经加拿大被运往欧洲。

Dr Humphries’s hypothesis is weakened by work published the year following his proposal, by Michael Worobey, an evolutionary anthropologist at the University of Arizona, Tucson. Dr Worobey suggests that the 1918 human flu virus was genetically related to a virus circulating in North American birds at the time. The truth, though, is unlikely to be known unless and until a comparison can be made between the genetic sequence of the 1918 virus (which was determined in 2005, by Jeffery Taubenberger and Ann Reid of the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology inWashington, DC) and the sequences of each of the putative ancestors, of which, at the moment, no known samples exist.

在汉弗莱斯提出自己的假说一年后,图森市亚利桑那州立大学进化人类学家迈克尔·沃洛比发表了一份研究报告,汉弗莱斯的推论也因此有些站不住脚了。沃洛比提出,1918年人流感病毒与当时在北美鸟类中播散的一种病毒存在基因关联。然而,无人可以知晓真相,除非将1918年病毒基因序列(已由华盛顿军队病理研究所的杰弗里·陶本伯格和安·里德于2005年测出)与每一个可能的祖先基因序列进行比对,而就目前来看,并不存在这些祖先的已知样本。

The Blue Death

蓝色死神

Whatever its origin, once Spanish flu got going it spread rapidly. It traversed the world in three waves, of which the second—that of the northern-hemisphere autumn of 1918—was the most severe. For that reason, the autumn of 2018 is marked by many as the epidemic’s centenary.

不论起源如何,西班牙流感一发生就迅速蔓延开来。它分为三个波次横扫全世界,其中第二波最为严重,于1918年秋天在北半球爆发。基于这一原因,很多人认为,到2018年秋天,大流行正好满一百年。

That second wave was preceded by a milder one in the spring of 1918 and succeeded by a final wave, intermediate in severity between the other two, in the early months of 1919. The disease lingered on, though, until at least March 1920, with cases being reported that month in Peru and Japan. Indeed, Dennis Shanks, an epidemiologist at the Australian Army Malaria Institute, in Queensland, recently reported that the epidemic continued on some Pacific islands for another year, with cases still being reported in New Caledonia as late as July 1921.

第二波之前是1918年春季情况较为轻微的那一波次,之后是最后一波,其严重程度介于其他两个波次之间,发生在1919年前几个月。至少直到1920年3月,该病才逐渐消弭,当月秘鲁和日本仍有病例报告。实际上,昆士兰澳大利亚陆军疟疾研究所流行病学家丹尼斯·山克斯最近报告说,之后该病在一些太平洋岛屿又持续流行了一年,最晚到1921年7月,新喀里多尼亚仍有病例报告。

In the mind of Paul Ewald, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Louisville, in Kentucky, the 1918 virus’s global reach and its particular virulence were shaped by a common factor. Both were a consequence of the trench warfare of the Western Front.

肯塔基州路易斯维尔大学的进化生物学家保罗·埃瓦尔德认为,1918年病毒之所以波及全球且具有特别强的毒力,有一个共同影响因素——它们都是西线战场阵地战(堑壕战)引发的后果。

Its virulence, in Dr Ewald’s view, was a result of the abnormal evolutionary environment that the trenches provided.Normally, natural selection causes a virus that is transmitted directly from host to host to moderate its virulence. The longer the host stays alive, the more new hosts that initial victim is likely to come into contact with. Less virulent strains are thus favoured, and so spread. Observation shows that such drops in virulence do, indeed, happen in most influenza epidemics.

在埃瓦尔德看来,1918大流感病毒的强毒力是由战壕中异常进化环境造成的。正常情况下,由于自然选择,当病毒直接在宿主之间传播时,其毒力也在减弱。宿主存活越久,初期受感染的宿主接触到的新宿主也就越多。毒力较弱的病毒株也从而得以留存,进而播散出去。观察报告显示,大多数流感疫情确实存在这种病毒毒力下降的现象。

Dr Ewald, however, suggests that the war forced the 1918 virus down a different evolutionary path. The large numbers of young men packed into trenches in eastern France for days or weeks on end were, first of all, living cheek by jowl, making contagion easy, and, second, quite likely to die of causes other than influenza before they could pass it on. In these circumstances the strategy favoured by selection would be to breed rapidly in a new host’s body, shedding lots of virus particles as this happens,even if that risks killing a host—for the host may soon be unavailable anyway.

可是,埃瓦尔德指出,战争让1918年病毒的进化“误入歧途”。大量年轻人涌入法国东部的战壕,一呆就是数日或数周,如此一来,首先,他们在一起亲密接触容易造成传染,其二,他们在把流感传染给他人之前非常有可能死于流感以外的原因。在这些环境条件下,自然选择所采取的策略可能是病毒在一个新宿主体内迅速繁殖,产生大量病毒颗粒,即使这样存在致使宿主死亡的风险,因为这个宿主也许很快就用不上了(根本不管宿主的死活,因为宿主本来也自身难保)。

Historians confirm that the virus did indeed race through the trenches, killing as it went. Those soldiers who survived then took it home with them when they went on leave. This process was exacerbated by the demobilisation which followed the armistice of November 1918that ended the fighting, with American, Australian, Canadian and New Zealand troops returning home, and also soldiers from the European combatants’ colonies in Africa and Asia.

历史学家证实,病毒确实在战壕中“赛跑”,所到之处毙命无数。那些幸存的战士后来在休假时,又把病毒带回家。1918年11月,停战协议签订,战争结束,随着美国、澳大利亚、加拿大、新西兰军队,以及来自欧洲参战国在非洲和亚洲殖民地的士兵回国,大量军人复员加速了这一进程。

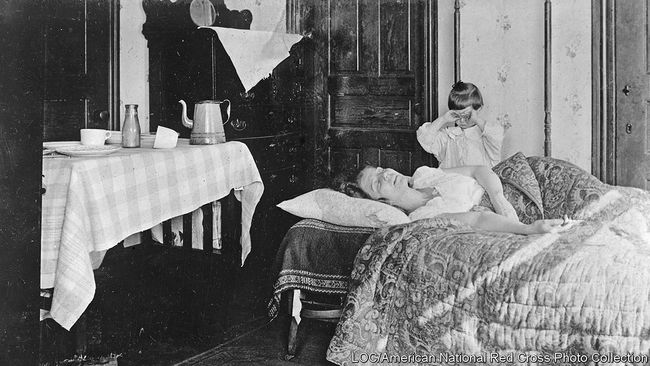

Most of those who fell ill from Spanish flu experienced nothing more than the symptoms of ordinary flu—a sore throat, fever and a headache. The unlucky, however, began to have difficulty breathing. Their faces took on a mahogany hue and they bled from their noses and mouths.Mahogany deepened to blue, an effect doctors dubbed “heliotrope cyanosis”, and before long their entire bodies turned black.

除了普通流感的症状如咽喉痛、发热和头痛之外,刚患上西班牙流感的患者大多数都没有其他不适。然而,不幸的人开始出现呼吸困难,脸部呈红褐色,口鼻出血。红褐色渐渐加深发青(也就是医生所称的“淡紫色发绀”效应),不久后浑身变成黑色。

The actual cause of death in most cases was pneumonia brought on by opportunistic bacteria. This made diagnosis complicated—for in 1918 the concept of a “virus” was a newish one. Most of the world’s doctors therefore thought they were dealing with a bacterial infection.The 1918 influenza thus appears in historical records under a kaleidoscope of labels ranging from the common cold to pneumonic plague. That is one reason why estimating the death toll accurately is hard.

大多数病例死亡的确切原因是细菌乘虚而入引起的肺炎。诊断因此变得棘手,因为在1918年,“病毒”这一概念还属于新生事物,当时全世界大多数医生都认为他们诊治的是一种细菌感染,进而造成历史上关于1918年大流感的记载,从普通感冒到肺鼠疫千变万化,纷然杂陈。之所以很难准确估计死亡人数,这也是原因之一。

At the molecular level, the explanation for the virulence of the Spanish flu remains unknown. But there are clues. Shortly after Dr Taubenberger and Dr Reid had worked out its genetic sequence, a group led by Terrence Tumpey, a virologist at the Centres for Disease Control andPrevention in Atlanta, Georgia, reconstructed the virus by feeding its genes to cultured human kidney cells in a dish, and forcing them to churn out viral particles in the way that human lung cells do during the normal process of infection. This reconstructed virus is now being studied at high-security biocontainment facilities in America.

目前还没有从分子水平解析西班牙流感病毒毒力的相关结论,不过线索已经有了。陶本伯格和里德测出其基因序列后不久,一个由佐治亚州亚特兰大的疾病控制与预防中心病毒学家泰伦斯·塔姆佩带领的研究小组重构了这一病毒,方法是将其基因注入培养皿中的人肾细胞,迫使其像正常感染过程中人肺细胞那样大量产生病毒颗粒。这一重组病毒目前正在美国高安全性生物防护设施内接受研究。

One promising line of inquiry is the 1918strain’s version of haemagglutinin, a surface protein that helps the virus break into a target cell. When this is swapped into a strain of virus normally almost harmless to mice, it makes that strain deadly.

有一种研究体系前景,那就是1918年病毒株的血凝素说。血凝素是病毒表面的一种蛋白,可以帮助病毒侵入靶细胞。当血凝素被替换进一种通常对小鼠几乎无毒的病毒株中,它会令那个病毒株变得致命。

Such work is controversial. Some critics point to possible military applications. Those working in the area, such as Dr Tumpey, prefer to emphasise its potential help to the job of creating better flu vaccines.

此类研究引发了争议。某些批评人士指出其可能应用于军事。这一领域的研究人员,比如塔姆佩博士,则更愿意强调其有助于推动研发更好的流感疫苗。

Never again?

再也不会发生?

The glittering prize of such work would be a universal vaccine—something that protects recipients against all possible versions of the virus. One approach to creating such a vaccine exploits the observation that, although the convoluted head of the haemagglutinin molecule(which is the target of most existing vaccines), is highly variable in its composition, the stem that anchors it to the rest of the virus is not. A vaccine aimed at the stem might thus be universally effective.

此类研究若想获得熠熠生辉的成果,就要创出一种通用型疫苗,保护接种者免受各种可能类型病毒的侵扰。观察发现,虽然血凝素分子(大多数现有疫苗的靶点)的弯曲头部组成千变万化,但其借以吸附在病毒其他部位的茎部是不变的。因此,针对茎部的疫苗可能是普遍有效的。如果我们注意到这一点并加以利用,造出通用疫苗的方法也就有了。

Vaccines which employ this principle are already in clinical trials. But even if they do work, they might not be as universal as their supporters hope. Sceptics point to a phenomenon called imprinting, that might cause a “universal” vaccine’s efficacy to vary between individuals who have had different histories of exposure to flu.

应用这一原理的疫苗现已进入临床试验。但是即使有效,它们也许还是不会让其拥趸如愿以偿,做不到普遍适用。怀疑人士指出一种被称为“印记”的现象,它可能会使“通用”疫苗的效用因个体流感接触史的差异而有所不同。

Imprinting is the name given to the observation that an immune system mounts its most effective response to the first flu strain it ever encounters. A memory of this first response is retained by the system and subsequent responses are therefore likely to be poor matches for new and different strains, whether caught from someone else or introduced by inoculation as vaccines. To the extent that haemagglutinin’s molecular stems really are the same in different strains, the effects of imprinting should be diminished. But they may not be abolished entirely.

人们观察发现免疫系统会对其遇到的第一个病毒株产生最有效的免疫应答,将这一现象取名为“印记”。免疫系统会保留这一首次应答记忆,后续应答因此可能无法准确针对新的不同的病毒株,不管是其他人传染的还是疫苗接种后引入的。不同病毒株的血凝素分子茎完全相同,基于此,“印记”作用的影响也会减弱,但并不会彻底消除。

Imprinting probably shaped the 1918pandemic. One of its surprises was that people in their twenties and thirties were particularly vulnerable, while the elderly—normally a high-risk group for flu—were actually more likely to survive than they had been in flu seasons throughout the previous decade. The first flu virus that most of those who were young adults in 1918 were exposed to as children was the one that caused the pandemic of the 1890s. This belonged to viral subtype H3N8 (subtypes are named after particular versions of haemagglutinin and a second surface protein, neuraminidase, that they contain), and was thus a different beast from the H1N1strain with which they were confronted in 1918, so imprinting would have harmed their response.

印记作用或许对1918年流感大流行产生了重要影响。那次大流行很多情况出乎意料,其中之一就是二三十岁的人特别容易被感染致命,而一般情况下属流感高危人群的老年人相比前几十年流感季,实际上存活率更高。1918年的青壮年大多数在儿时就已经最先接触过流感病毒,而那个病毒是引起19世纪90年代大流行的病毒,属于H3N8亚型(亚型是指病毒中所包含的血凝素与另一种表面蛋白神经氨酸酶的特定变体),而他们在1918年遭遇的是H1N1病毒株,对于后者(H1N1)而言,就成了不同的动物宿主,于是印记作用就可能损坏他们的免疫应答。

By contrast, there is evidence that those who were elderly in 1918 had often been exposed when young to viruses circulating earlier in the 19th century which contained H1 or N1. In their cases, imprinting would have helped their resistance mechanisms.

相比之下,有证据显示,1918年的老人年轻时候常常接触早在19世纪初期就已经传播的病毒,其中就包含H1或N1。对他们而言,印记作用则会促进其免疫防御系统。

Understanding imprinting could assist efforts to predict who will come off worst in a future pandemic, and to build abetter universal vaccine. The imprinting story is unlikely to be simple,though. For example, there seems to be cross-reactivity between some subtypes of influenza, meaning that exposure to one offers protection against another.America’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases is planning a large study of imprinting in infants, to explore these effects.

了解印记作用,有助于预测在未来的大流行中谁最倒霉,并研发一种更好的通用疫苗。不过,关于印记绝非三言两语可以说清。例如,流感的某些亚型之间似乎有交叉反应,这意味着接触一种亚型可以防御另一种亚型。美国国家过敏和传染病研究所正计划一项针对婴儿印记现象的大型研究,以探讨这些影响。

The better vaccines promised by this sort of research are one arm of an effective response to a new pandemic. The other is early detection. The world has, thankfully, moved on from the point where a high-ranking health official can stand up four months into a flu pandemic and be ignorant of the situation in countries beyond his own. But the ability of a virus to spread around the world has increased hugely.

这类研究有望发现更好的疫苗,将为有效应对新的大流行助一臂之力。另一个办法是早期检测。令人欣慰的是,现今的世界不会再有哪个高级卫生官员在大流行都已经持续4个月了还站着不动,而且对本国以外的情况一无所知。但是病毒在世界各地传播的能力却大大增加了。

Troops demobilised after the first world war went home by railway and ship. Now, passenger airliners mean that a virus in one part of the planet could cross to that place’s antipodes in a day.Moreover, though humanity at large is not as crowded together as were the troops in the trenches, the world’s population has quadrupled since 1918. About half of it now lives in cities, with a proximity between neighbours unknown to the far more rural world of a century ago. Monitoring systems are much better than they were in 1918, so the chances are that a threatening influenza outbreak would be picked up quickly. But the conditions needed for a pandemic to happen do exist. As with liberty, so with health: the price of retaining it is eternal vigilance.

一战结束后遣散的部队乘火车和轮船返回家乡。现如今,客运班机意味着一种病毒可以在一天之内从地球的一端横跨到另一端。再者说了,尽管一般情况下人类不会像战壕里的军队那样挤在一起,但是自1918年至今,世界人口已经增长了4倍,其中接近半数居住在城市,邻里之间相距很近,而这种情况对于一个世纪前以农村为主的世界而言是并不存在的。相比1918年,现在的监测系统先进得多,因此任何有可能流感爆发的迹象都会很快被发现。不过,发生大范围流行的客观条件仍确实存在。自由也好,健康也罢,要想拥有,就要永远警醒。