The art of ancient Greece (about 500B.C.—30B.C.) and Rome (about 300 B.C. ---500 A.D.) is called Classical Art. In their art, the Greeks and Romans celebrated the beauty of the human body and the greatness of their gods.

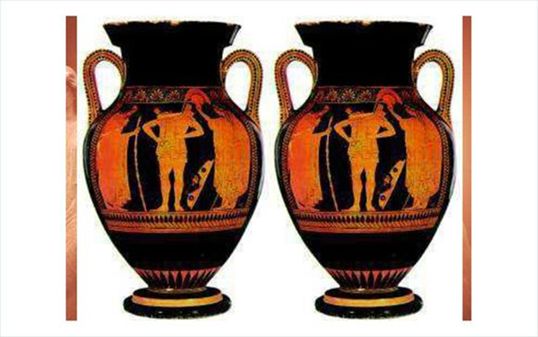

Painting on pottery

Painted pottery was one of the highest forms of art in ancient Greece. The Greeks were skilled at using a potter’s wheel. They painted their pottery with scenes of daily life and stories of gods and heroes. Instead of paint, they used slip, a mixture of clay and water, to decorate the pottery. The pottery was heated up, or fired, in a very hot oven called a kiln.

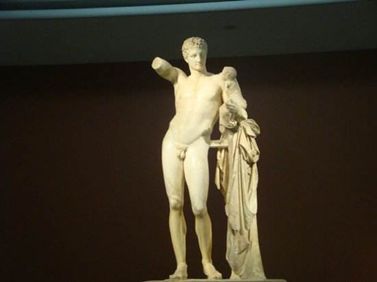

Greek sculpture

The Greeks were masters at sculpture.Traditional sculpture is three-dimensional art that can be viewed from all sides. Most Greek sculpture was of people. Unlike the Egyptians, Greek artists aimed to show humans in a natural way.

The Greeks chiseled marble for their sculpture, and they also used cast bronze. To do this, they first made the sculpture out of clay. Next, they covered the clay with wax and added another layer of clay over it. When the entire piece was fired, the high heat melted the wax, leaving a gap between the layers of clay. Then, melted bronze was poured into this gap. When it cooled, the clay coating was removed, leaving behind the bronze statue.

Roman sculpture

After the Romans conquered Greece, they modeled their own sculptures after those by Greek artists, who they very much admired. The Romans carved busts, or head sculptures, of important people. They gave them realistic faces and features unique to that person. These busts were the first true facial likenesses in art history.

Further Reading

1. There is no living body quite as symmetrical, well-built and beautiful as those of the Greek statues. People often think that what the artists did was to look at many models and to leave out any feature they did not like; that they started by carefully copying the appearance of a real man, and then beautified it by omitting any irregularities or traits which did not conform to their idea of a perfect body. They say that Greekartists “idealized” nature, and they think of it in terms of a photographer who touches up a portrait by deleting small blemishes. But a touched-up photograph and an idealized statue usually lack character and vigor. So much has been left out and deleted that little remains but a pale and insipid ghost of the model. The Greek approach was really exactly the opposite. Through all these centuries, the artists we have been discussing were concerned with infusing more and more life into the ancient husks. In the time of Praxiteles their method bore its ripest fruits. The old types had begun to move and breathe under the hands of the skillful sculptor, and they stand before us like real human beings, and yet as beings from a different, better world. They are, in fact, beings from a different world, not because the Greeks were healthier or more beautiful than other men --- there is no reason to think they were --- but because art at the moment had reached a point at which the typical and the individual were poisedin a new and delicate balance.

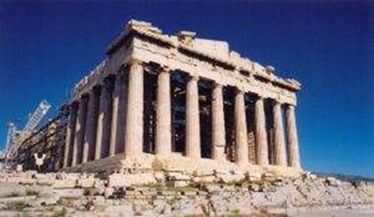

2. Phidias, also spelled Pheidias (flourished c. 490–430 bc), Athenian sculptor, the artistic director of the construction of the Parthenon, who created its most important religious images and supervised and probably designed its overall sculptural decoration. He established forever general conceptions of Zeus and Athena.

The two great works of Pheidias are the great idol of Pallas Athene made for her shrine in the Parthenon and the famous statue of Zeus in Olympia. Both of them have been irretrievably lost, but the temples in which they were placed still exist. What we can see now are only their second hand copies made in Roman times for travelers and collectors as souvenirs, and as decorations for gardens or publicbaths. We must be very grateful for these copies, because they give us at least a faint idea of the famous masterpieces of Greek art; but unless we use our imagination these weak imitations can also do much harm.

The long band or frieze that ran high up round the inside of the Parthenon is another classical representation of Greek sculpture. It depicted the annual procession on the solemn festival of the goddess.

3. The statue of a charioteer has been found in Delphi. His head is amazingly different from the general idea one may easily form of Greek art when one only looks at copies. The eyes, which often look so blank and expressionless in marble statues or are empty in bronze heads, are marked in coloured stones --- as they always were at that time. The hair, eyes and lips were slightly gilt, which gave an effect of richness and warmth to the whole face. And yet such a head never looked gaudy or vulgar.

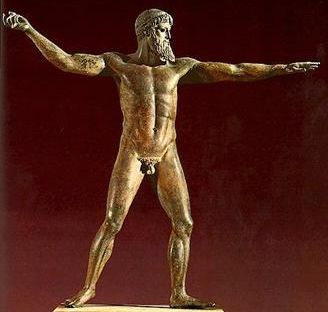

4. Discobolos (Discus thrower) by the Athenian sculptor Myron, who probably belonged to the same generation as Pheidias: The young athlete was represented at the moment when he is just about to hurl the heavy discus. Various copies of this work have been found. The attitude looks so convincing that modern athletes have taken it for a model and have tried to learn from it the exact Greek style of throwing the discus.

From the statue, we still can see its relation to the tradition of Egyptian art. Like the Egyptian painters, Myron has given us the trunk in front view, the legs and arms in side view; like them he has composed his picture of a man’s body out of the most characteristic views of its parts.But under his hands this old and outworn formula has become something entirely different. Instead of fitting these views together into an unconvincing likeness of a rigid pose, he asked a real model to take up a similar attitude and so adapted it that it seems like a convincing representation of a body in motion. Whether or not this corresponds to the exact movement most suitable for throwing the discus is hardly relevant. What matters is that Myron conquered movement just as the painters of his time conquered space.

5. Every Greek work from that great period shows the wisdom and skill in the distribution of figures, but what the Greeks of the time valued even more was something else: the new-found freedom to represent the human body in any position or movement could be used to reflect the inner life of the figures represented. We hear from one of his disciples that this is what the great philosopher Socrates, who had himself been trained as a sculptor, urged artists to do. They should represent the“workings of the soul” by accurately observing the way “feelings affect the body in action”.

References:

1. Heather Alexander, A Child’sIntroduction to Art, Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers, New York, 2014.

2. E.H.Gombrich, The Story of Art.

3. 蒋勋,《写给大家的西方艺术史》,湖南美术出版社,2015年7月。

By Emily

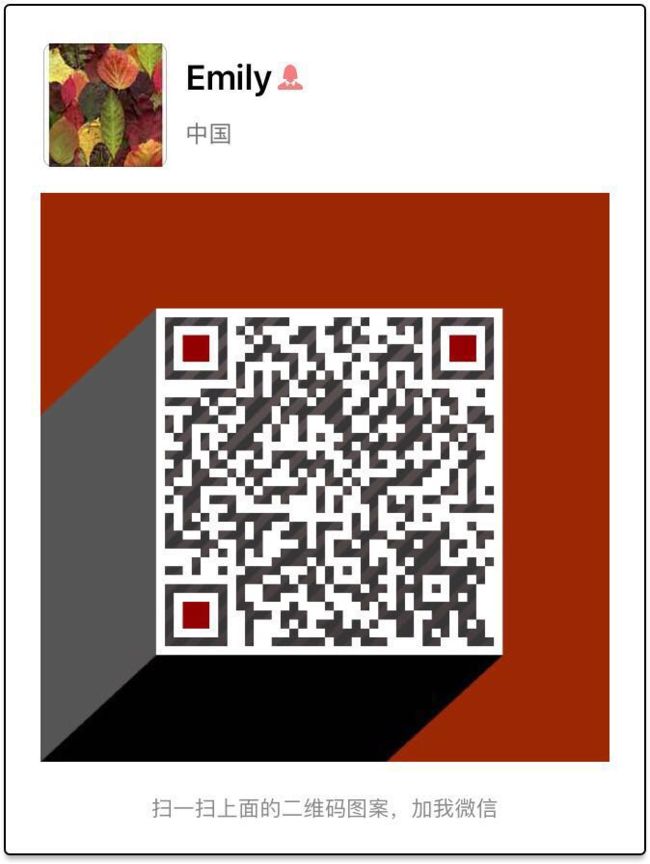

WeChat: emily_109