For one of China’s most powerful investors, Guan Jun is surprisingly difficult to track down. On a sweltering July afternoon in Beijing, two Bloomberg

staffers set out to find Guan, who until recently controlled a stake in airlines-to-finance conglomerate HNA Group Co. that on paper was worth almost $18 billion. The first stop was the headquarters of cosmetics company Beijing Mei Yue Xi Beauty Technology Ltd., which corporate registries indicate Guan controls. On the fifth floor of a nondescriptbuilding in a quiet neighborhood of the capital, the office was empty and locked. A man in

the hallway said whoever worked there had moved away a couple of months before.

Another dead end: an apartment that Guan listed as his address in Hong Kong filings. The current tenant, who would give only her surname,Sui, said the apartment was owned by Guan’s wife until she sold it about a year before. Sui said she couldn’t provide new contact details. The story was similar at the local branch of Oriental Aphrodite Beauty Spa, a provider of pedicures and massages that media reports have suggested Guan once owned. Two managers said they couldn’t recall anyone by that name.

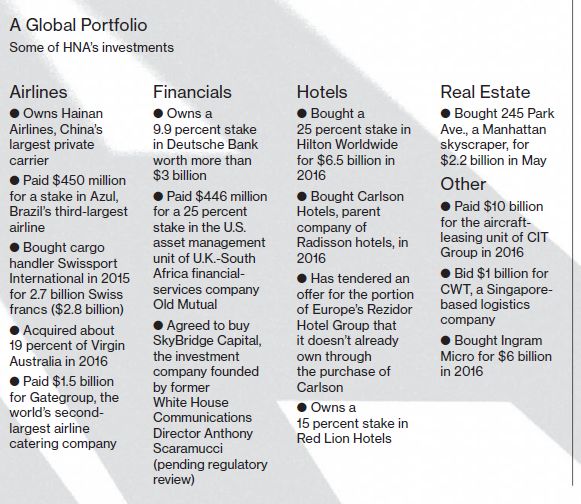

The elusiveness of Guan, who’s never given an interview or been seen at a public event, is in keeping with the broader murkiness of privately held HNA.Despite an impenetrable corporate structure that makes its true ownership difficult to discern, it has vaulted from provincial obscurity to become one of China’s most prolific global dealmakers. HNA now owns about 10 percent of Deutsche Bank AG and a quarter of Hilton Worldwide Holdings Inc., and acquired the global aircraft leasing business of CIT Group Inc., and the airport ground- handling giant Swissport International Ltd. It also has a huge portfolio of blue chip real estate, including a tower on New York’s Park Avenue that it picked up for $2.2 billion in May. Late last year it completed one of the largest takeovers of a U.S. company by a Chinese buyer when it purchased computer distributor Ingram Micro Inc. for about $6 billion. It’s also seeking approval for a roughly $200 million acquisition of SkyBridge Capital, the hedge fund company owned by ousted White House Communications Director Anthony Scaramucci, part of its growing push into global financial services.

All those deals advance what HNA’s 64-year-old founder and chairman, Chen Feng, has said is his goal to build the company into one of the world’s 50 largest. He’s well on his way. In 2016 HNA—which says it’s now owned by its managers and a pair of charities to which Guan, who has no executive role, earlier this year transferred his stake—more than doubled its total assets, to about $150 billion.The purchases have put HNA, along with China’s other mergers and acquisitions titans, in the government’s crosshairs as President Xi Jinping’s Communist Party clamps down on mounting debt and capital outflows to protect the yuan from weakening further. China’s banking and foreign-exchange regulators are reviewing loans and deals linked to the likes of HNA, Dalian Wanda Group, Anbang Insurance Group, and Fosun International Ltd.,which has purchased Club Méditerranée SA and Cirque du Soleil Inc., to see whether their shopping sprees resulted in any violations, people familiar with the matter have told Bloomberg.

That’s increasing pressure on HNA and its acquisitive brethren to halt their purchases, sell assets, or invest domestically. After announcing more than $30 billion in deals in 2016, HNA has declared only about $10 billion of investments in 2017, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. And some of its deals are shaky. In Singapore, the purchase of logistics operator CWT Ltd. and the initial public offering of an HNA-backed property trust are facing delays, according to people familiar with the matter. HNA says it wants to continue to make acquisitions in core areas such as transport, even while its overall pace of dealmaking slows.

HNA isn’t alone in feeling the heat. Billionaire Wang Jianlin’s Wanda in July agreed to sell most of his theme-park and hotel assets, reversing a longstanding strategy to build an entertainment empire that could challengeWalt Disney Co.Wang recently told Caixin magazine that he’s decided to focus his investments at home. And Chinese authorities have taken the extraordinary step of asking Anbang,owner of New York’s Waldorf Astoria hotel, to sell its offshore assets, according to people familiar with the matter.

Meanwhile, long-whispered questions about HNA’s ownership and finances have burst into the open. In April an exiled Chinese businessman, Guo

Wengui, made explosive allegations of financial connections between the company and top Communist Party officials. (HNA denied Guo’s allegations and sued him for defamation.) More recently, Bank of America Merrill Lynch told bankers they shouldn’t pitch HNA for new acquisitions or fundraisings because of concerns about its debt and ownership structure, according to people familiar with the matter.Morgan Stanley and Citigroup Inc., too, have largely steered clear of the company. Other lenders are asking hard questions about the conglomerate’s financial stability.

“It goes back to the old cliché: If you can’t stand the heat, get out of the kitchen,” says Steve Tsang,director of London’s SOAS China Institute. “If you’re going to be operating on the international scene as a major global investor, you’re going to be getting serious scrutiny.” HNA denies thatWall Street banks are shunning the company or that it’s under any particular scrutiny from other lenders. Bank of America,Citigroup, andMorgan Stanley declined to comment.Chen makes no secret of his desire for HNA to serve as an exemplar of Chinese capitalism. The company’s skyscraping headquarters on the tropical vacation island of Hainan is designed to resemblea seated Buddha, and the chairman says he wants to develop a management style that melds Western and Confucian cultural concepts. In public he almost always appears wearing a Mandarincollar suit. He says he unwinds by practicing classical calligraphy.

HNA traces its roots to a more frenetic period in China’s history, the go-go atmosphere of the country’s late-20th century economic opening. After

trading a job in China’s air force for a role as a lowlevel government official, Chen set out in the early 1990s to start an airline to serve Hainan. At first it was so small that the founder himself had to serve drinks in the aisle of its sole Boeing 737. But Chen soon made a powerful friend: George Soros, who invested $25 million in fledgling Hainan Airlines in 1995 and later doubled that bet. The carrier grew rapidly as its home province became a popular destination for domestic tourists, and in 2006, Chen expanded beyond the mainland, acquiring two airlines in Hong Kong.

Then came deals for international assets such as Spain’s NH Hotel Group, a container-shipping company, and a stake in France’s second-largest airline. Over the past couple of years that acquisition campaign accelerated, with transportationrelated deals that included a stake in Rio de Janeiro’s main airport and the acquisition of flight caterer Gategroup Holding AG, as well as investments in companies in a smattering of other sectors: a consumerloan provider in New Zealand, prime development land in Hong Kong, the owner of Radisson Hotels, a company linked to the respected Chinese business magazine Caijing, and, this year, the pending deal for SkyBridge.

As it snapped up global assets, HNA sought to announce its arrival in more than just financial terms. In late June it invited a top-drawer crowd of French politicians, bankers, and socialites to a glitzy banquet at the beaux-arts Petit Palais in central Paris, with a menu of lobster and candied duck curated by celebrity chef Joel Robuchon. Chen was celebrating his birthday with a performance of Chinese opera and the announcement of a series of charitable donations by HNA.

Although Hainan is a profitable airline, HNA’s rapid expansion has been possible only thanks to enormous amounts of debt—a load it says is sustainable but some analysts believe is risky. The company, which relies mainly on Chinese banks,has borrowed more than $73 billion and secured about $90 billion in credit lines, according to its latest annual report. For collateral, HNA has pledged at least $24 billion in shares of companies it has invested in, filings show—meaning that if the stocks’ prices were to fall far enough, it could be forced to sell assets quickly at depressed prices to repay debt.Even among debt-hungry Chinese companies, HNA “is fairly extreme in terms of its leverage,” says Nigel Stevenson, an analyst at GMT Research.

At the same time, some Western governments have become less open to HNA’s approaches. In July a deal for a stake in Global Eagle Entertainment Inc., a provider of in-flight Wi-Fi, fell apart after the parties were unable to win approval from the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS), which reviews the security implications of acquisitions by overseas companies. CFIUS previously waved through the Ingram Micro deal,which gave HNA access to the U.S. company’s cloud technology for logistics. The European Central Bank is also considering a review of HNA’s relationship with Deutsche Bank, Germany’s largest lender, part of a procedure that looks at an investor’s finances and the origin of its funds.

With questions mounting about its operations,HNA in late July made what it said was a full disclosure of its ownership structure. About half the company is controlled by a group of 12 executives, it said, while the remainder is owned by two charities it created, one in China and another in New York,named for the Chinese deity Cihang. Guan, HNA Chief Executive Officer Adam Tan told the Financial Times, “had just held the stake for us,” before transferring it to other shareholders in recent months.If Chen and Tan thought their announcement would put questions about HNA’s structure to rest, they were wrong. New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman said the local Cihang foundation wasn’t registered as a charity in the state and made a formal request for detailed information on its officers and affiliates. According to the foundation’s federal tax return, it had no assets at the end of 2016, and HNA has yet to provide specifics on its current or planned philanthropic activities. The company has said it intends to comply fully with New York rules.

“Any company that has the aspirations for size and impact that HNA has will have to bemuch more open in terms of its organization, its governance,and its ownership than most Chinese firms have been to date,” says William Kirby, a professor at Harvard Business School and author of a case study on HNA. The company “may not have anticipated how quickly these questions would come as they rise in prominence.”

In the meantime, Scaramucci’s brief tenure in the White House has put HNA’s ownership and influence on the U.S. political radar as well. CFIUS is still reviewing the offer for SkyBridge, which hedge fund industry veterans said upon announcement of the deal in January valued the company at a higher-than-average level. “We do not know who owns HNA,” says Paul Ryan, vice president for policy and litigation at transparency organization Common Cause, “so we do not know who is buying a big stake in SkyBridge.” For HNA, that’s been par for the course.—Matthew Campbell, with Dong Lyu, Ruth David, and Ken Wills