Linux 内存管理之memory compaction

Memory compaction

It's worth noting that, in one way, this problem is actually getting worse.

Contemporary processors are not limited to 4K pages; they can work with much larger pages ("huge pages")

in portions of a process's address space.

There can be real performance advantages to using huge pages,

mostly as a result of reduced pressure on the processor's translation lookaside buffer.

But the use of huge pages requires that the system be able to find physically-contiguous areas of memory

which are not only big enough, but which are properly aligned as well.

Finding that kind of space can be quite challenging on systems

which have been running for any period of time.

Over the years, the kernel developers have made various attempts to mitigate this problem;

techniques like ZONE_MOVABLE and lumpy reclaim have been the result.

There is still more that can be done, though, especially in the area of fixing fragmentation

to recover larger chunks of memory. After taking a break from this area, Mel Gorman has recently

returned with a new patch set implementing memory compaction. Here we'll take a quick look at how this patch works.

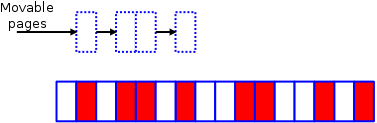

Imagine a very small memory zone which looks like this:

Here, the white pages are free, while those in red are allocated to some use.

As can be seen, the zone is quite fragmented, with no contiguous blocks of

larger than two pages available; any attempt to allocate, for example,

a four-page block from this zone will fail. Indeed, even two-page allocations will fail,

since none of the free pairs of pages are properly aligned.

It's time to call in the compaction code. This code runs as two separate algorithms;

the first of them starts at the bottom of the zone and builds a list of allocated pages which could be moved:

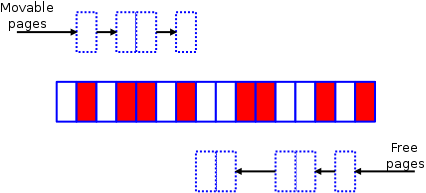

Meanwhile, at the top of the zone, the other half of the algorithm is creating a list of free pages

which could be used as the target of page migration:

Eventually the two algorithms will meet somewhere toward the middle of the zone.

At that point, it's mostly just a matter of invoking the page migration code

(which is not just for NUMA systems anymore)

to shift the used pages to the free space at the top of the zone, yielding a pretty picture like this:

We now have a nice, eight-page, contiguous span of free space which can

be used to satisfy higher-order allocations if need be.

Of course, the picture given here has been simplified considerably from

what happens on a real system. To begin with, the memory zones will

be much larger; that means there's more work to do, but the resulting

free areas may be much larger as well.

But all this only works if the pages in question can actually be moved.

Not all pages can be moved at will; only those which are addressed through

a layer of indirection and which are not otherwise pinned down are movable.

So most user-space pages - which are accessed through user virtual addresses - can be moved;

all that is needed is to tweak the relevant page table entries accordingly.

Most memory used by the kernel directly cannot be moved - though some of it is reclaimable,

meaning that it can be freed entirely on demand.

It only takes one non-movable page to ruin a contiguous segment of memory.

The good news here is that the kernel already takes care to separate movable and non-movable pages,

so, in reality, non-movable pages should be a smaller problem than one might think.

The running of the compaction algorithm can be triggered in either of two ways.

One is to write a node number to /proc/sys/vm/compact_node, causing compaction

to happen on the indicated NUMA node. The other is for the system to fail in an attempt

to allocate a higher-order page; in this case, compaction will run as a preferable alternative to

freeing pages through direct reclaim. In the absence of an explicit trigger,

the compaction algorithm will stay idle; there is a cost to moving pages around

which is best avoided if it is not needed.

Mel ran some simple tests showing that, with compaction enabled, he was able

to allocate over 90% of the system's memory as huge pages while simultaneously

decreasing the amount of reclaim activity needed. So it looks like a useful bit of work.

It is memory management code, though, so the amount of time required to get into the mainline

is never easy to predict in advance.