来自国外Kotin 布道师的 完整版【Kotlin 简明教程】1

A Productive and Pragmatic Language

A programming language is usually designed with a specific purpose in mind. This purpose can be anything from serving a specific environment (e.g, the web) to a certain paradigm (e.g. functional programming). In the case of Kotlin the goal is to build a productive and pragmatic language, that has all the features that a developer needs and makes easy to use them.

Kotlin was initially designed to work with other JVM languages, but it is now evolved to be much more: it also works in the browser and as a native application.

This is what Dmitry Jemerov, development lead at JetBrains said about their choice of creating Kotlin:

We’ve looked at all of the existing JVM languages, and none of them meet our needs. Scala has the right features, but its most obvious deficiency is very slow compilation

For a more in-depth comparison between Scala and Kotlin you can see our article: Kotlin vs Scala: Which Problems Do They Solve?

Why not keeping using Java? Java is a good language but has a series of issues because of its age and success: it needs to maintain backward compatibility with a lot of old code and it suffers from old design principles.

Kotlin is multi-paradigm, with support for object-oriented, procedural and functional programming paradigms, without forcing to use any of them. For example, contrary to Java, you can define functions as top-level, without having to declare them inside a class.

In short, Kotlin was designed to be a better Java, that takes all the best practices and add a few innovations to make it the most productive JVM language out there.

A Multi-platform Language from the Java World

It is no secret that Kotlin comes from the Java world. JetBrains, the company behind the language has long experience in developing tools for Java and they specifically thought about the issues in developing with Java. In fact, one of the core objectives of Kotlin is creating code that is compatible with an existing Java code base. One reason is because the main demographics of Kotlin users are Java developers in search of a better language. However, it is inter-operable also to support working with both languages. You can maintain old code in Java e create a new project in Kotlin without issues.

It has been quite successful in that and this is the reason because Google has chosen to officially support Kotlin as a first-class language for Android development.

The main consequence is that, if you come from the Java world, you can immediately start using Kotlin in your existing Java projects. Also, you will found familiar tools: the great IntelliJ IDEA IDE and build tools likes Gradle or Maven. If you have never used Java that is still good news: you can take advantage of a production ready infrastructure.

However, Kotlin is not just a better Java that also has special support for Android. You can also use Kotlin in the browser, working with existing JavaScript code and even compile Kotlin to a native executable, that can take advantage of C/C++ libraries. Thanks to native executables you can use Kotlin on an embedded platform.

So, it does not matter which platform you use or which language you already know, if you search for a productive and pragmatic language Kotlin is for you.

A Few Kotlin Features

Here there are a quick summary of Kotlin features:

- 100% interoperable with Java

- 100% compatible with Java 6 and so can you can create apps for most Android devices

- Runs on the JVM, it can be transpiled to JavaScript and can even run native, with interoperability with C and Objective-C (macOs and iOS) libraries

- There is no need to end statements with a semicolon

;. Blocks of code are delimited by curly brackets{ } - First-class support for constant values and immutable collections (great for parallel and functional programming)

- Functions can be top-level elements (i.e., there is no need to put everything inside a class)

- Functions are first-class citizens: they can be passed around just like any other type and used as argument of functions. Lambda (i.e., anonymous functions) are greatly supported by the standard library

- There is no keyword

static, instead there are better alternatives - Data classes, special classes designed to hold data

- Everything is an expression:

if,for, etc. they can all return values - The

whenexpression is like a switch with superpowers

Table of Contents

The companion repository for this article is available on GitHub

- Setup

Basics of Kotlin

- Variables and Values

- Types

- Nullability

- Kotlin Strings are Awesome

- Declaring and Using Functions

- Classes

- Data Classes

- Control Flow

- The Great when Expression

- Dealing Safely with Type Comparisons

- Collections

- Exceptions

- A Simple Kotlin Program

Advanced Kotlin

- Higher-order Functions

- Lambdas

- Generic Types

- A Few Niceties

- Using Kotlin for a Real Project

- Summary

Setup

As we mentioned, you can use Kotlin on multiple platforms and in different ways. If you are still unsure if you want to develop with Kotlin you can start with the online development environment: Try Kotlin. It comes with a few exercises to get the feel of the language.

In this setup section, we are going to see how to setup the most common environment to build a generic Kotlin application. We are going to see how to setup IntelliJ IDEA for Kotlin development on the JVM. Since Kotlin is included in all recent versions of IntelliJ IDEA you just have to downloadand install the IDE.

You can get the free Community edition for all platforms: Windows, MacOS and Linux.

Basic Project

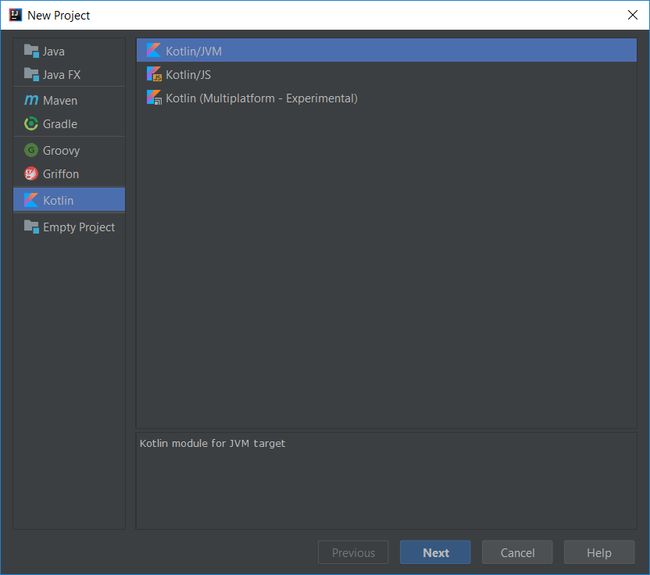

You can create a new Kotlin project very easily, just launch the wizard and choose the template.

Then you have to fill the details of your project, the only required value is the Project name, you can leave the other settings to their default value.

Now that you have a project you can look at its structure and create a Kotlin file inside the srcfolder.

This is the basic setup, which is good for when you need to create a pure Kotlin project with just your own code. It is the ideal kind of project for your initial Kotlin programs, since it is easier and quicker to setup.

Gradle Project

In this section we are going to see how to create a Gradle project. This is the kind of project you are going to use the most with real projects, since it easily allows to mix Java and Kotlin code, both your own code and libraries from other people. That is because Gradle facilitates download and use existing libraries, instead of having to download them manually.

You can create a new Gradle project quite easily, just launch the wizard, choose the Gradle template and select **Kotlin (Java) **in the section Additional Libraries and Frameworks.

Then you have to fill the naming details of your project, needed for every Gradle project. You have to indicate a name for your organization (GroupId) and for the specific project (ArtifactID). In this example we choose the names **strumenta **(i.e., the company behind SuperKotlin) for our organization and books for our project.

Then you have to specify some Gradle settings, but you can usually just click Next for this stage.

Finally, you have to fill the details of your project, the only required value is the Project name, you can leave the other settings to their default value. The value should already be filled, with the ArtifactId value chose in one of the preceding steps.

Now that you have a project you can look at its structure and create a Kotlin file inside the src/main/kotlin folder. Given that you can mix Java and Kotlin code there are two folders: one for each language. The structure of a Java project is peculiar: in a Java project, the hierarchy of directories matched the package structure (i.e., the logical organization of the code). For example, if a Java file is part of a package com.strumenta.books it will be inside the folders com/strumenta/books.

With Kotlin you do not have to respect this organization, although it is the recommended if you plan to use both Java and Kotlin. Instead if you just use Kotlin you should use whatever structure your prefer.

Adding Kotlin Code

Inside the new Kotlin file you can create the main routine/function. IntelliJ IDEA comes with a template, so you simply need to write main and press tab to have it appear.

When you code is ready, you can compile it and run the program with the proper menu or clicking the icon next to main function.

And that is all you need to know to setup and start developing with Kotlin.

Basics of Kotlin

In this section we explain the basic elements of Kotlin. You will learn about the basic elements needed to create a Kotlin program: definining variables, understanding the type system, how Kotklin supports nullability and how it deals with strings. You will learn how to us the builing blocks like control flow expressions, functions, classes and how to define the special Kotlin classes known as data classes. Finally, we will put everything together to create a simple program.

Variables and Values

Kotlin is a multi-paradigm language, which includes good support for functional programming. It is a completely functional language like Haskell, but it has the most useful features of functional programming. An important part of this support is that constant values are first class citizens of Kotlin, just like normal variables.

Constants are called value and are declared using the keyword val.

val three = 3

This is as simple as declaring a variable, the difference, of course, is that to declare a variable you use the keyword var.

var number = 3

If you try to reassign a value you get a compiler error:

Val cannot be reassigned

This first-class support for values is important for one reason: functional programming. In functional programming the use constant values allow some optimizations that increase performance. For instance, calculations can be parallelized since there is a guarantee that the value will not change between two parallel runs, given that it cannot change.

As you can see, in Kotlin there is no need to end statements with a semicolon, a newline is enough. However, adding them is not an error: it is no required, but it is allowed. Though remember that Kotlin is not Python: blocks of code are delimited by curly braces and not indentation. This is an example of the pragmatic approach of the language.

Note: outside this chapter, when we use the term variable we usually also talk about value, unless explicitly noted.

Types

Kotlin is statically-typed language, which means that types of any variable must be determined at compilation time. Up until now, we have declared variables and values without indicating any type, because we have provided an initialization value. This initialization allows the Kotlin compiler to automatically infer the type of the variable or value.

Obviously, you can explicitly assign a type to a variable. This is required, if you do not provide an initialization value.

val three: Int = 3

In this example, the value three has the type Int.

Whether you explicitly indicate the type of a value or not, you always have to initialize it, because a value cannot be changed.

The types available in Kotlin are the usual ones: Char, String, Boolean, several types of numbers.

There are 4 types of natural numbers: Byte, Short, Int, Long.

| Type | Bit Width |

|---|---|

| Byte | 8 |

| Short | 16 |

| Int | 32 |

| Long | 64 |

A Long literal must end with the suffix L.

There are also two types for real numbers: Float and Double.

| Type | Bit Width | Example Literal |

|---|---|---|

| Float | 32 | 1.0f |

| Double | 64 | 1.0 |

Float and Double literals use different formats, notice the suffix f for float.

Since Kotlin 1.1 you can use underscore between digits, to improve readability of large numeric literals.

For example, this is valid code.

var large = 1_000_000

A Type is Fixed

Even when you are not explicitly indicating the type, the initial inferred type is fixed and cannot be changed. So, the following is an error.

var number = 3

// this is an error

number = "string"

This remains true even if there is a type that could satisfy both the initial assignment and the subsequent one.

var number = 1

// this is an error

number = 2.0

In this example number has the type Int, but the second assignment has the type Double. So, the second assignment is invalid, despite the fact that an Int value could be converted to a Double. So, if number was a Double it could accept integer numbers.

In fact, to avoid similar errors, Kotlin is quite strict even when inferring the type to literals. For example, an integer literal will always just be an integer literal and it will not be automatically converted to a double.

var number = 1.0

// this is an error

number = 2

In the previous example the compiler will give you the following error, relative to the second assignment:

The integer literal does not conform to the expected type Double

However, complex expressions, like the following one, are perfectly valid.

var number = 1.0

number = 2 + 3.0

This works because the whole addition expression is of type Double. Even though the first operand of the addition expression is an Int, that is automatically converted to Double.

Kotlin usually prefers a pragmatic approach, so this strictness can seem out of character. However, Kotlin has another design principle: to reduce the number of errors in the code. This is the same principle that dictates the Kotlin approach to nullability.

Nullability

In the last few years best practices suggest being cautious in using null and nullable variables. That is because using null references is handy but prone to errors. It is handy because sometimes there is not a meaningful value to use to initialize a variable. It is also useful to use a null value to indicate the absence of a proper value. However, the issue is that sometimes the developer forgets to check that a value is valid, so you get bugs.

Tony Hoare, the inventor of the null reference call it its billion-dollar mistake:

I call it my billion-dollar mistake. It was the invention of the null reference in 1965. At that time, I was designing the first comprehensive type system for references in an object oriented language (ALGOL W). My goal was to ensure that all use of references should be absolutely safe, with checking performed automatically by the compiler. But I couldn’t resist the temptation to put in a null reference, simply because it was so easy to implement. This has led to innumerable errors, vulnerabilities, and system crashes, which have probably caused a billion dollars of pain and damage in the last forty years.

That is why in Kotlin, by default, you must pay attention when using null values. Whether it is a string, an array or a number, you cannot assign a null value to a variable.

var text: String = "Test"

text = "Changing idea"

// this is an error

text = null

The last assignment will make the compiler throw an error:

Null can not (sic) be a value of a non-null type String

As this error indicates, you cannot use null with standard types, but there is a way to use null values. All you have to do is indicating to the compiler that you want to use a nullable type. You can do that by adding a ? at the end of a type.

var text: String = null // it does not compile

var unsafeText: String? = null // ok

Nullability Checks

Kotlin takes advantage of the nullability or, at the opposite, the safeness of types, at all levels. For instance, it is taken into consideration during checks.

val size = unsafeText.length // it does not compile because it could be null

if (unsafeText != null) {

val size = unsafeText.length // it works, but it is not the best way

}

When using nullable type you are required to check that the variable currently has a valid value before accessing it. After you have checked that a nullable type is currently not null, you can use the variable as usual. You can use as if it were not nullable, because inside the block it is safe to use. Of course, this also looks cumbersome, but there is a better way, that is equivalent and more concise.

val size = unsafeText?.length // it works

The safe call operator (?.) guarantees that the variable will be accessed only if unsafeText it is not null. If the variable is null then the safe call operator returns null. So, in this example the type of the variable size would be Int?.

Another operator related to null-values is the elvis operator (?:). If whatever is on the left of the elvis operator is not null then the elvis operator returns whatever is on the left, otherwise it returns what is on the right.

val len = text?.length ?: -1

This example combines the safe-call operator and the elvis operator:

- if text is not null (safe-call) then on the left there will be the length of the string text, thus the elvis operator will return

text.length - if text is

null(safe-call) then on the left there will benull, then the elvis operator will return-1.

Finally, there is the non-null assertion operator (!!). This operator converts any value to the non-null corresponding type. For example, a variable of type String? becomes of a value of type String. If the value to be converted is null then the operator throws an exception.

// it prints the length of text or throws an exception depending on whether text is null or not

println(text!!.length)

This operator has to be used with caution, only when you are absolutely certain that the expression is not null.

Kotlin Strings are Awesome

Kotlin strings are powerful: they come with plenty of features and a few variants.

Strings are immutable, so whenever you are modifying a new string you are actually creating a new one. The elements of a string can be accessed with the indexing operator ([]).

var text:String = "Kotlin is awesome"

// it prints K

println(text[0])

You can escape some special characters using a backslash. The escape sequences supported are: \t, \b, \n, \r, \', \", \\ and \$. You can use the Unicode escape sequence syntax to input any character by referencing its code point. For example, \u0037 is equivalent to 7.

You can concatenate strings using the + operator, as in many other languages.

var text:String = "Kotlin"

// it prints "Kotlin is awesome"

println(text + " is awesome")

However, there is a better way to concatenate them: string templates. These are expressions that can be used directly inside a string and are evaluated, instead of being printed as they are. These expressions are prefixed with a $. If you want to use arbitrary expression, you have to put them inside curly braces, together with the dollar sign (e.g., ${4 + 3}).

fun main(args: Array) {

val who: String = "john"

// simple string template expression

// it prints "john is awesome"

println("$who is awesome")

// arbitrary string template expression

// it prints "7 is 7"

println("${4 + 3} is 7")

}

This feature is commonly known as string interpolation*. *It is very useful, and you are going to use it all the time.

However, it is not a panacea. Sometimes you have to store long, multi-line text, and for that normal strings are not good, even with templates. In such cases you can use raw strings, delimited by triple double quotes """.

val multiline = """Hello,

I finally wrote this email.

Sorry for the delay, but I didn't know what to write.

I still don't.

So, bye $who."""

Raw strings support string templates, but not escape sequences. There is also an issue due to formatting: given that the IDE automatically indent the text, if you try to print this string you are going to see the initial whitespace for each line.

Luckily Kotlin include a function that deals with that issue: trimMargin. This function will remove all leading whitespace up until the character you used as argument. It will also remove the character itself. If you do not indicate any character, the default one used is |.

val multiline = """Hello,

|I finally wrote the email.

|Sorry for the delay, but I didn't know what to write.

|I still don't.

|So, bye $who.""".trimMargin()

This will create a string without the leading whitespace.

Declaring and Using Functions

To declare a function, you need to use the keyword fun followed by an identifier, parameters between parentheses, the return type. Then obviously you add the code of the function between curly braces. The return type is optional. If it is not specified it is assumed that the function does not return anything meaningful.

For example, this is how to declare the main function.

fun main(args: Array) {

// code here

}

The main function must be present in each Kotlin program. It accepts an array of strings as parameter and returns nothing. If a function returns nothing, the return type can be omitted. In such cases the type inferred is Unit. This is a special type that indicates that a function does not return any meaningful value, basically is what other languages call void.

So, these two declarations are equivalent.

fun tellMe(): Unit {

println("You are the best")

}

// equivalent to the first one

fun tell_me() {

println("You are the best")

}

As we have seen, functions can be first-class citizens: in Kotlin classes/interfaces are not the only first-level entities that you can use.

If a function signature indicates that the function returns something, it must actually return something with the proper type using the return keyword.

fun tellMe(): String {

return "You are the best"

}

The only exception is when a function return Unit. In that case you can use return or return Unit, but you can also omit them.

fun tellNothing(): Unit {

println("Don't tell me anything! I already know.")

// either of the two is valid, but both are usually omitted

return

return Unit

}

Function parameters have names and types, types cannot be omitted. The format of an argument is: name followed by colon and a type.

fun tell(who: String, what: String): String {

return "$who is $what"

}

Function Arguments

In Kotlin, function arguments can use names and default values. This simplifies reading and understanding at the call site and allows to limit the number of function overloads. Because you do not have to make a new function for every argument that is optional, you just put a default value on the definition.

fun drawText(x: Int = 0, y: Int = 0, size: Int = 20, spacing: Int = 0, text: String)

{ [..] }

Calling the same function with different arguments.

// using default values

drawText("kneel in front of the Kotlin master!")

// using named arguments

drawText(10, 25, size = 20, spacing = 5, "hello")

Single-Expression Functions

If a function returns a single expression, the body of the function is not indicated between curly braces. Instead, you can indicate the body of the function using a format like the assignment.

fun number_raised_to_the_power_of_two(number: Int) = number * number

You can explicitly indicate the type returned by a single-expression function. However, it can also be omitted, even when return something meaningful (i.e. not Unit) since the compiler can easily infer the type of the expression returned.

Classes

Classes are essentially custom types: a group of variables and methods united in a coherent structure.

Classes are declared using the keyword class followed by a name and a body.

class Info {

[..]

}

How do you use a class? There is no keyword new in Kotlin, so to instantiate an object you just call a constructor of the object.

val info = Info()

Properties

You cannot declare fields directly inside a class, instead you declare properties.

class Info {

var description = "A great idea"

}

These properties look and behave suspiciously like simple fields: you can assign values to them and access their values just like any other simple variable.

val info = Info()

// it prints "A great idea"

println(info.description)

info.description = "A mediocre idea"

// it prints "A mediocre idea"

println(info.description)

However, behind the scenes the compiler converts them to properties with a hidden backing field. I.e., each property has a backing field that is accessible through a getter and a setter. When you assign a value to a property the compiler calls the setter. and when you read its value the compiler calls a getter to obtain it. In fact, you can alter the default behavior of a property and create a custom getter and/or* setter*.

Inside these custom accessors you can access the backing field using the identifier field. You can access the value passed to the setter using the identifier value. You cannot use these identifiers outside the custom accessors.

class Info {

var description = "A great idea"

var name: String = ""

get() = "\"$field\""

set(value) {

field = value.capitalize()

}

}

Let’s see the property name in action.

info.name = "john"

// it prints "John" (quotes included)

println(info.name)

Kotlin offers the best of both worlds: you can automatically have properties, that can be used as easily as simple fields, but if you need soem special behavior you can also create custom accessors.

Constructors

If the class has a primary constructor it can be into the class header, following the class name. It can also be prefixed with the keyword constructor. A primary constructor is one that is always called, either directly or eventually by other constructors. In the following example, the two declarations are equivalent.

// these two declarations are equivalent

class Info (var name: String, var number: Int) { }

class Info constructor (var name: String, var number: Int) { }

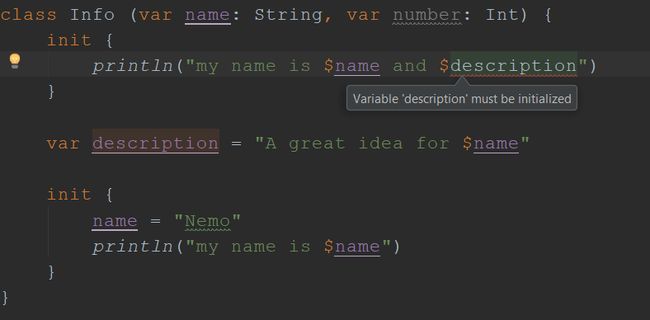

You cannot include any code inside the primary constructor. Instead, if you need to do any initialization, you can use initializer blocks. There can be many initializer blocks; they are executed in the order in which they are written. This means that they are not all executed before the initialization of the object, but right where they appear.

class Info (var name: String, var number: Int) {

init {

println("my name is $name")

}

var description = "A great idea for $name"

init {

name = "Nemo"

println("my name is $name")

}

}

// into the main function

fun main(args: Array) {

val info = Info("John", 5)

}

When the program executes it will prints the two strings in the order in which they appear.

If you try to use the description property in an initializer blocks that is before the property is defined you will get an error.

A class can also have secondary constructors, which can be defined with the keyword constructor. Secondary constructors must eventually call the primary constructor: they can do that directly or through another secondary constructor.

class Info (var name: String, var number: Int) {

constructor(name: String) : this(name, 0) {

this.name = name.capitalize()

}

}

There are a couple of interesting things going on in this example: we see how to call a primary constructor and an important difference between primary and secondary constructors. To call a primary constructor you use the this keyword and supply the argument to the constructor after the constructor signature. The important difference between secondary and primary constructors is that the parameters of **primary constructors can define properties **while the parameters of a secondary constructor are always just parameters.

If the parameters of a primary constructor are also properties they will be accessible throughout all the lifecycle of the object, just like normal properties. While, if they are simple parameters, they are obviously accessible only inside the constructor, just like any other parameter of a function.

You can automatically define a property with a parameter of a primary constructor simply putting the keywords val or var in front of the parameter.

In this example, the primary constructor of the first class defines properties, while the second does not.

// class with primary constructor that defines properties

class Info (var name: String, var number: Int)

// class with primary constructor that does not define properties

class Info (name: String, number: Int)

Inheritance

A class can inherit from another base class to get properties and functions of the base class. This way you can avoid repetition and build an hierarchy of classes that goes from the most generic to the most precise. In Kotlin, a class can only inherits from one other base class.

If a class does include an explicit base class, it implicitly inherits from the superclass Any.

// it implicitly inherits from Any

class Basic

The class Any has only a few basic methods, like equals and toString.

A derived class must call a constructor of the base class. This call can happen in different ways and it is reflected in the syntax of a class. The syntax to make a class derive from another requires to add, after the name of the derived class, a colon and a reference to the base class. This reference can be either the name of the class or a constructor of the base class.

The difference depends on whether the derived class has a primary constructor or not. If the derived class has no primary constructor, it needs to call a constructor of the base class in its secondary constructors, otherwise it can call it directly in its primary constructor.

Let’s see a few examples to clarify this statement.

// the derived class has no primary constructor

class Derived : Base {

// calling the base constructor with super()

constructor(p: Int) : super() {

}

}

// the derived class has a primary constructor

class Derived(p: Int) : Base(p)

You cannot use super (used to call the base constructor) inside the code of the constructor. In other words, super is not a normal expression or function.

Notice that if the derived class has a primary constructor you must call the constructor of the base class there. You cannot call it later in a secondary constructor. So, there are two alternatives, but there is no choice: you have to use one or the other depending on the context.

Create a Base Class and Overriding Elements

Kotlin requires an explicit syntax when indicating classes that can be derived from.

This means that this code is wrong.

class NotABase(p: Int)

class Derived(p: Int) : NotABase(p)

It will show the following error:

This type is final, so it cannot be inherited from

You can only derive from a class if the class is explicitly marked as open.

open class Base(p: Int)

class Derived(p: Int) : Base(p)

You also need an explicit syntax when a class has elements that can be overridden. For example, if you want to override a method or a property of a base class. The difference is that you have both to use the modifier open on the element of the base class and the modifier override on the element of the derived class. The lack of either of these two modifiers will result in an error.

open class Base(p: Int) {

open val text = "base"

open fun shout() {}

}

class Derived(p: Int) : Base(p) {

override val text = "derived"

override fun shout() {}

}

This approach makes for a clearer and safer design. The official Kotlin documentation says that the designers chose it because of the book Effective Java, 3rd Edition, Item 19: Design and document for inheritance or else prohibit it.

Data Classes

Frequently the best way to group semantically connected data is to create a class to hold it. For such a class, you need a a few utility functions to access the data and manipulate it (e.g., to copy an object). Kotlin includes a specific type of class just for this scope: a data class.

Kotlin gives all that you typically need automatically, simply by using the data keyword in front of the class definition.

data class User(val name: String, var password: String, val age: Int)

That is all you need. Now you get for free:

- getters and setters (these only for variable references) to read and write all properties

-

component1()..componentN()for all properties in the order of their declaration. These are used for destructuring declarations (we are going to see them later) -

equals(),hashCode()andcopy()to manage objects (ie. compare and copy them) -

toString()to output an object in the human readable formName_of_the_class(Name_of_the_variable=Value_of_the_variable, [..])"

For example, given the previous data class User

val john = User("john","secret!Shhh!", 20)

// it prints "john"

println(john.component1())

// mostly used automagically in destructuring declaration like this one

val (name, password, age) = john

// it prints 20

println(age)

// it prints "User(name=john, password=secret!Shhh!, age=20)"

println(john)

It is a very useful feature to save time, especially when compared to Java, that does not offer a way to automatically create properties or compare objects.

There are only a few requirements to use a data class:

- the primary constructor must have at least one parameter

- all primary constructor parameters must be properties (i.e., they must be preceded by a

varorval)

Control Flow

Kotlin has 4 control flow constructs: if, when, for and while. If and when are expressions, so they return a value; for and while are statements, so they do not return a value. If and when can also be used as statements, that is to say they can be used standalone and without returning a value.

If

An if expression can have a branch of one statement or a block.

var top = 0

if (a < b) top = b

// With else and blocks

if (a > b) {

top = a

} else {

top = b

}

When a branch has a block, the value returned is the last expression in the block.

// returns a or b

val top = if (a > b) a else b

// With blocks

// returns a or 5

var top = if (a > 5) {

println("a is greater than 5")

a

} else {

println("5 is greater than a")

5

}

Given that if is an expression there is no need for a ternary operator (condition ? then : else), since an if with an else branch can fulfill this role.

For and Ranges

A for loop iterates through the elements of a collection. So, it does not behave like a for statement in a language like C/C++, but more like a foreach statement in C#.

The basic format of a for statement is like this.

for (element in collection) {

print(element)

}

To be more precise, the Kotlin documentation says that for iterates through everything that provides an iterator, which means:

- has a member- or extension-function iterator(), whose return type

- contains a member or extension-function next(), and

- contains a member or extension-function hasNext() that returns Boolean.

The Kotlin for can also behave like a traditional for loop, thanks to range expressions. These are expressions that define a list of elements between two extremes, using the operator .. .

// it prints "1 2 3 4 "

for (e in 1..4)

print("$e ")

Range expressions are particularly useful in for loops, but they can also be used in if or when conditions.

if (a in 1..5)

println("a is inside the range")

Ranges cannot be defined in descending order using the .. operator. The following is valid code (i.e., the compiler does not show an error), but it does not do anything.

// it prints nothing

for (e in 4..1)

print("$e ")

Instead, if you need to define an iteration over a range in descending order, you use downTo in place of the ...

// it prints "4 3 2 1 "

for (e in 4 downTo 1)

print("$e ")

There are also other functions that you can use in ranges and for loops: step and until. The first one dictates the amount you add or subtract for the next loop; the second one indicates an exclusive range, i.e., the last number is not included in the range.

// it prints "6 4 2 "

for (e in 6 downTo 1 step 2)

print("$e ")

// it prints "1 6 "

for (e in 1..10 step 5)

print("$e ")

// it prints "1 2 "

for (e in 1 until 3)

print("$e ")

While

The while and do .. while statements works as you would expect.

while (a > 0) {

a--

}

do {

a--

print("i'm printing")

} while (a > 0)

The when statement is a great feature of Kotlin that deserves its own section.

The Great when Expression

In Kotlin when replaces and enhances the traditional switch statement. A traditional switch is basically just a statement that can substitute a series of simple if/else that make basic checks. So, you can only use a switch to perform an action when one specific variable has a certain precise value. This is quite limited and useful only in a few circumstances.

Instead when can offer much more than that:

- can be used as an expression or a statement (i.e., it can return a value or not)

- has a better and safer design

- can have arbitrary condition expressions

- can be used without an argument

Let’s see an example of all of these features.

A Safe and Powerful Design

First of all, when has a better design. It is more concise and powerful than a traditional switch.

when(number) {

0 -> println("Invalid number")

1, 2 -> println("Number too low")

3 -> println("Number correct")

4 -> println("Number too high, but acceptable")

else -> println("Number too high")

}

Compared to a traditional switch, when is more concise:

- no complex case/break groups, only the condition followed by

-> - it can group two or more equivalent choices, separating them with a comma

Instead of having a default branch, when has an else branch. The else branch branch is required if when is used as an expression. So, if when returns a value, there must be an else branch.

var result = when(number) {

0 -> "Invalid number"

1, 2 -> "Number too low"

3 -> "Number correct"

4 -> "Number too high, but acceptable"

else -> "Number too high"

}

// with number = 1, it prints "when returned "Number too low""

println("when returned \"$result\"")

This is due to the safe approach of Kotlin. This way there are fewer bugs, because it can guarantee that when always assigns a proper value.

In fact, the only exception to this rule is if the compiler can guarantee that when always returns a value. So, if the normal branches cover all possible values then there is no need for an else branch.

val check = true

val result = when(check) {

true -> println("it's true")

false -> println("it's false")

}

Given that check has a Boolean type it can only have to possible values, so the two branches cover all cases and this when expression is guaranteed to assign a valid value to result.

Arbitrary Condition Branches

The when construct can also have arbitrary conditions, not just simple constants.

For instance, it can have a range as a condition.

var result = when(number) {

0 -> "Invalid number"

1, 2 -> "Number too low"

3 -> "Number correct"

in 4..10 -> "Number too high, but acceptable"

!in 100..Int.MAX_VALUE -> "Number too high, but solvable"

else -> "Number too high"

}

This example also shows something important about the behavior of when. If you think about the 5th branch, the one with the negative range check, you will notice something odd: it actually covers all the previous branches, too. That is to say if a number is 0, is also not between 100 and the maximum value of Int, and obviously the same is true for 1 or 6, so the branches overlap.

This is an interesting feature, but it can lead to confusion and bugs, if you are not aware of it. The compiler solves the ambiguity by looking at the order in which you write the branches. **The construct when can have branches that overlap, in case of multiple matches the first branch is chosen. **Which means that is important to pay attention to the order in which you write the branches: it is not irrelevant, it has meaning and can have consequences.

The range expressions are not the only complex conditions that you can use. The when construct can also use functions, is expressions, etc. as conditions.

fun isValidType(x: Any) = when(x) {

is String -> print("It's a string")

specialType(x) -> print("It's an acceptable type")

else -> false

}

The Type of a when Condition

In short, when is an expressive and powerful construct, that can be used whenever you need to deal with multiple possibilities.

What you cannot do, is using conditions that return incompatible types. In a condition, you can use a function that accepts any argument, but it must return a type compatible with the type of the argument of the when construct.

For instance, if the argument is of type Int you can use a function that accepts any number of arguments, but it must returns an Int. It cannot return a String or a Boolean.

var result = when(number) {

0 -> "Invalid number"

// OK: check returns an Int

check(number) -> "Valid number"

// OK: check returns an Int, even though it accepts a String argument

checkString(text) -> "Valid number"

// ERROR: not valid

false -> "Invalid condition"

else -> "Number too high"

}

In this case, the false condition is an example of an invalid condition, that you cannot use with an argument of type Int.

Using when Without an Argument

The last interesting feature of when is that you can use it without an argument. In such case it acts as a nicer if-else chain: the conditions are Boolean expressions. As always, the first branch that matches is chosen. Given that these are boolean expression, it means that the first condition that results True is chosen.

when {

number > 5 -> print("number is higher than five")

text == "hello" -> print("number is low, but you can say hello")

}

The advantage is that a when expression is cleaner and easier to understand than a chain of if-else statements.

If you want to know more about when you can read a whole article about it: Kotlin when: A switch with Superpowers.

Dealing Safely with Type Comparisons

To check if an object is of a specific type you can use the is expression (also known as is operator). To check that an object is not of a certain typee you can use the negated version !is.

if (obj is Double)

println(obj + 3.0)

if (obj !is String) {

println(obj)

}

If you need to cast an object there is the as operator. This operator has two forms: the safe and unsafe cast.

The unsafe version is the plain as. It throws an exception if the cast is not possible.

val number = 27

// this throws an exception because number is an Int

var large = number as Double

The safe version as? instead returns null in case the cast fails.

val number = 27

var large: Double? = number as? Double

In this example the cast returns null, but now it does not throw an exception. Notice that the variable that holds the result of a safe cast must be able to hold a null result. So, the following will not compile.

val number = 27

// it does not compile because large cannot accept a null value

var large: Double = number as? Double

The compile will show the following error:

Type mismatch: inferred type is Double? but Double was expected

On the other hand, is perfectly fine to try casting to a type that it cannot hold null. So, the as? Double part of the previous example is valid code. In other words, you do not need to write as? Double?. As long as the variables that holds the result can accept a null, you can try to cast to any compatible type. The last part is important, because you cannot compile code that tries to cast to a type that it cannot be accepted.

So, the following example is an error and does not compile.

var large: Double? = number as? String

The following does, but large is inferred to be of type String?.

var large = number as? String

Smart Casts

Kotlin is a language that takes into account both safety and the productivity, we have already seen an example of this attitude when looking at the when expression. Another good example of this approach are smart casts: the compiler automatically inserts safe casts if they are needed, when using an is expression. This saves you from the effort of putting them yourself or continually using the safe call operator (?.).

A smart cast works with if, when and while expressions. That is an example with when.

when (x) {

is Int -> print(x + 1)

is String -> print(x.length + 1)

is IntArray -> print(x.sum())

}

If it were not for smart cast you would have to do the casting yourself or using the safe call operator. That how you would have to write the previous example.

when (x) {

is Int -> {

if (x != null)

print(x + 1)

}

is String -> print(x?.length + 1)

is IntArray -> print(x?.sum())

}

Smart casts works also on the right side of an and (&&) or or (||) operator.

// x is automatically cast to string for x.length > 0

if (x is String && x.length > 0) {

print(x.length)

}

The important thing to remember is that you cannot use smart casts with variable properties. That is because the compiler cannot guarantee that they were not modified somewhere else in the code. You can use them with normal variables.

Collections

Kotlin supports three standard collections: List, Map and Set:

- List is a generic collection of elements with a precise order

- Set is a generic collection of unique elements without a defined order

- Map is a collection of pairs of key-value pairs

A rather unique feature of Kotlin is that collections comes both in a mutable and immutable form. This precise control on when and which collections can be modified is helpful in reducing bugs.

Collections have a standard series of functions to sort and manipulate them, such as sort, or first. They are quite obvious and we are not going to see them one by one. However, we are going to see the most powerful and Kotlin-specific functions later in the advanced section.

Lists

val numbers: MutableList = mutableListOf(1, 2, 3)

val fixedNumbers: List = listOf(1, 2)

numbers.add(5)

numbers.add(3)

println(numbers) // it prints [1, 2, 3, 5, 3]

A list can contain elements of the same type in the order in which they are inserted. It can contain identical elements. Notice that there is no specific syntax to create a list, a set or a map, you need to use the appropriate function of the standard library. To create a MutableList you use mutableListOf, to create an immutable List you use listOf.

Sets

val uniqueNumbers: MutableSet = mutableSetOf(1,3,2)

uniqueNumbers.add(4)

uniqueNumbers.add(3)

println(uniqueNumbers) // it prints [1, 3, 2, 4]

A set can contain elements of the same type in the order in which they are inserted, but they must be unique. So, if you try again an element which is already in the set, the addition is ignored.

Notice that there is no specific syntax to create a list, a set or a map, you need to use the appropriate function of the standard library. To create a MutableSet you use mutableSetOf, to create an immutable Set you use setOf.

There are also other options to create a set, such as hashSetOf or sortedSetOf. These functions may have different features (e.g., the elements are always sorted) or be backed by different elements (e.g., an HashMap).

Maps

val map: MutableMap = mutableMapOf(1 to "three", 2 to "three", 3 to "five")

println(map[2]) // it prints "three"

for((key, value) in map.entries) {

println("The key is $key with value $value")

}

// it prints:

// The key is 1 with value three

// The key is 2 with value three

// The key is 3 with value five

A map is like an associative array: each element is a pair made up of a key and an associated value. The key is unique for all the collection. Notice that there is no specific syntax to create a list, a set or a map, you need to use the appropriate function of the standard library. To create a MutableMapyou use mutableMapOf, to create an immutable Map you use mapOf.

You can easily iterate through a map thanks to the property entries which returns a collection of keys and values.

Immutable and Read-Only Collections

Kotlin does not distinguish between an immutable collection and a read-only view of a collection. This means, for instance, that if you create a List from a MutableList you cannot change the list directly, but the underlying list can change anyway. This could happen if you modify it through the MutableList. This holds true for all kinds of collections.

val books: MutableList = mutableListOf("The Lord of the Rings", "Ubik")

val readOnlyBooks: List = books

books.add("1984")

// it does not compile

readOnlyBooks.add("1984")

// however...

println(readOnlyBooks) // it prints [The Lord of the Rings, Ubik, 1984]

In this example you cannot add directly to the list readOnlyBooks, however if you change booksthen it would also change readOnlyBooks.

Exceptions

An exception is an error that requires special handling. If the situation cannot be resolved the program ends abruptly. If you can handle the situation you have to catch the exception and solve the issue.

The Kotlin syntax for throwing and catching exceptions is the same as Java or most other languages.

Throw Expression

To throw an exception you use the expression throw.

// to throw an exception

throw Exception("Error!")

You can throw a generic exception, or create a custom exception that derives from another Exception class.

class CustomException(error: String) : Exception(error)

throw CustomException("Error!")

In Kotlin throw is an expression, so it can return a value of type Nothing. This is a special type with no values. It indicates code that will never be reached. You can also use this type directly, for example as return type in a function to indicate that it never returns.

fun errorMessage(message: String): Nothing {

println(message)

throw Exception(message)

}

This type can also come up with type inference. The nullable variant of this type (i.e., Nothing?) has one valid value: null. So, if you use null to initialize a variable whose type is inferred the compiler will infer the type Nothing?.

var something = null // something has type Nothing?

Try Expression

To catch an exception you need to wrap the try expression around the code that could launch the exception.

try {

// code

}

catch (e: Exception) {

// handling the exception

}

finally {

// code that is always executed

}

The finally block contains code that is always executed no matter what. It is useful to make some cleaning, like closing open files or freeing resources. You can use any number of catch block and one finally block, but there should be at least one of either blocks. So, there must be at least one between finally and catch blocks.

try {

// code

}

catch (e: CustomException) {

// handling the exception

}

If you want to catch only an expection of a certain type you can set it as argument of catch. In this code we only catch exceptions of type CustomException.

try {

// code

}

catch (e: Exception) {

// handling all exceptions

}

If you want to catch all exceptions you can use the catch with the argument of type Exception, which is the base class of all exceptions. Alternatively you can use the finally block alone.

try {

// code

}

finally {

// code that is always executed

}

Try is an expression, so it can return a result. The returned value is the last expression of the try or catch blocks. The finally block cannot return anything.

val result: String = try { getResult() } catch (e: Exception) { "" }

In this example we wrap the call to a function getResult() in a try expression. If the function returns normally we initialize the value result with the value returned by it, otherwise we initialize it with an empty string.

待续2

Kotlin 开发者社区

国内第一Kotlin 开发者社区公众号,主要分享、交流 Kotlin 编程语言、Spring Boot、Android、React.js/Node.js、函数式编程、编程思想等相关主题。