Sorting

Introduction

Sorting is ordering a list of objects. We can distinguish two types of sorting. If the number of objects is small enough to fits into the main memory, sorting is called internal sorting. If the number of objects is so large that some of them reside on external storage during the sort, it is called external sorting. In this chapter we consider the following internal sorting algorithms

- Bucket sort

- Bubble sort

- Insertion sort

- Selection sort

- Heapsort

- Mergesort

O(n) algorithms

Bucket Sort

Suppose we need to sort an array of positive integers {3,11,2,9,1,5}. A bucket sort works as follows: create an array of size 11. Then, go through the input array and place integer 3 into a second array at index 3, integer 11 at index 11 and so on. We will end up with a sorted list in the second array.

Suppose we are sorting a large number of local phone numbers, for example, all residential phone numbers in the 412 area code region (about 1 million) We sort the numbers without use of comparisons in the following way. Create an a bit array of size 107. It takes about 1Mb. Set all bits to 0. For each phone number turn-on the bit indexed by that phone number. Finally, walk through the array and for each bit 1 record its index, which is a phone number.

We immediately see two drawbacks to this sorting algorithm. Firstly, we must know how to handle duplicates. Secondly, we must know the maximum value in the unsorted array.. Thirdly, we must have enough memory - it may be impossible to declare an array large enough on some systems.

The first problem is solved by using linked lists, attached to each array index. All duplicates for that bucket will be stored in the list. Another possible solution is to have a counter. As an example let us sort 3, 2, 4, 2, 3, 5. We start with an array of 5 counters set to zero.

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Moving through the array we increment counters:

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

Next,we simply read off the number of each occurrence: 2 2 3 3 4 5.

O(n2) algorithms

Bubble Sort

The algorithm works by comparing each item in the list with the item next to it, and swapping them if required. In other words, the largest element has bubbled to the top of the array. The algorithm repeats this process until it makes a pass all the way through the list without swapping any items.

void bubbleSort(int ar[])

{

for (int i = (ar.length - 1); i >= 0; i--)

{

for (int j = 1; j ≤ i; j++)

{

if (ar[j-1] > ar[j])

{

int temp = ar[j-1];

ar[j-1] = ar[j];

ar[j] = temp;

} } } }

Example. Here is one step of the algorithm. The largest element - 7 - is bubbled to the top:

7, 5, 2, 4, 3, 9

5, 7, 2, 4, 3, 9

5, 2, 7, 4, 3, 9

5, 2, 4, 7, 3, 9

5, 2, 4, 3, 7, 9

5, 2, 4, 3, 7, 9

The worst-case runtime complexity is O(n2). See explanation below

Selection Sort

The algorithm works by selecting the smallest unsorted item and then swapping it with the item in the next position to be filled.

The selection sort works as follows: you look through the entire array for the smallest element, once you find it you swap it (the smallest element) with the first element of the array. Then you look for the smallest element in the remaining array (an array without the first element) and swap it with the second element. Then you look for the smallest element in the remaining array (an array without first and second elements) and swap it with the third element, and so on. Here is an example,

void selectionSort(int[] ar){

for (int i = 0; i ‹ ar.length-1; i++)

{

int min = i;

for (int j = i+1; j ‹ ar.length; j++)

if (ar[j] ‹ ar[min]) min = j;

int temp = ar[i];

ar[i] = ar[min];

ar[min] = temp;

} }

Example.

29, 64, 73, 34, 20,

20, 64, 73, 34, 29,

20, 29, 73, 34, 64

20, 29, 34, 73, 64

20, 29, 34, 64, 73

The worst-case runtime complexity is O(n2).

Insertion Sort

To sort unordered list of elements, we remove its entries one at a time and then insert each of them into a sorted part (initially empty):

void insertionSort(int[] ar)

{

for (int i=1; i ‹ ar.length; i++)

{

int index = ar[i]; int j = i;

while (j > 0 && ar[j-1] > index)

{

ar[j] = ar[j-1];

j--;

}

ar[j] = index;

} }

Example. We color a sorted part in green, and an unsorted part in black. Here is an insertion sort step by step. We take an element from unsorted part and compare it with elements in sorted part, moving form right to left.

29, 20, 73, 34, 64

29, 20, 73, 34, 64

20, 29, 73, 34, 64

20, 29, 73, 34, 64

20, 29, 34, 73, 64

20, 29, 34, 64, 73

Let us compute the worst-time complexity of the insertion sort. In sorting the most expensive part is a comparison of two elements. Surely that is a dominant factor in the running time. We will calculate the number of comparisons of an array of N elements:

we need 0 comparisons to insert the first element

we need 1 comparison to insert the second element

we need 2 comparisons to insert the third element

...

we need (N-1) comparisons (at most) to insert the last element

Totally,

1 + 2 + 3 + ... + (N-1) = O(n2)

The worst-case runtimecomplexity is O(n2).What is the best-case runtime complexity? O(n). The advantage of insertion sort comparing it to the previous two sorting algorithm is that insertion sort runs in linear time on nearly sorted data.

O(n log n) algorithms

Mergesort

Merge-sort is based on the divide-and-conquer paradigm. It involves the following three steps:

- Divide the array into two (or more) subarrays

- Sort each subarray (Conquer)

- Merge them into one (in a smart way!)

Example. Consider the following array of numbers

27 10 12 25 34 16 15 31

- divide it into two parts

27 10 12 25 34 16 15 31divide each part into two parts27 10 12 25 34 16 15 31divide each part into two parts27 10 12 25 34 16 15 31merge (cleverly-!) parts

10 27 12 25 16 34 15 31merge parts10 12 25 27 15 16 31 34merge parts into one10 12 15 16 25 27 31 34

How do we merge two sorted subarrays? We define three references at the front of each array.

We keep picking the smallest element and move it to a temporary array, incrementing the corresponding indices.

![]()

See implementation details in in MergeSort.java.

Complexity of Mergesort

Suppose T(n) is the number of comparisons needed to sort an array of n elements by the MergeSort algorithm. By splitting an array in two parts we reduced a problem to sorting two parts but smaller sizes, namely n/2. Each part can be sort in T(n/2). Finally, on the last step we perform n-1 comparisons to merge these two parts in one. All together, we have the following equation

T(n) = 2*T(n/2) + n - 1

The solution to this equation is beyond the scope of this course. However I will give you a resoning using a binary tree. We visualize the mergesort dividing process as a tree

Lower bound

What is the lower bound (the least running time in the worst-case) for all sorting comparison algorithms? A lower bound is a mathematical argument saying you can't hope to go faster than a certain amount. The preceding section presented O(n log n) mergesort, but is this the best we can do? In this section we show that any sorting algorithm that sorts using comparisons must make O(n log n) such comparisons.

Suppose we have N elements. How many different arrangements can you make? There are N possible choices for the first element, (N-1) possible choices for the second element, .. and so on. Multiplying them, we get N! (N factorial.)

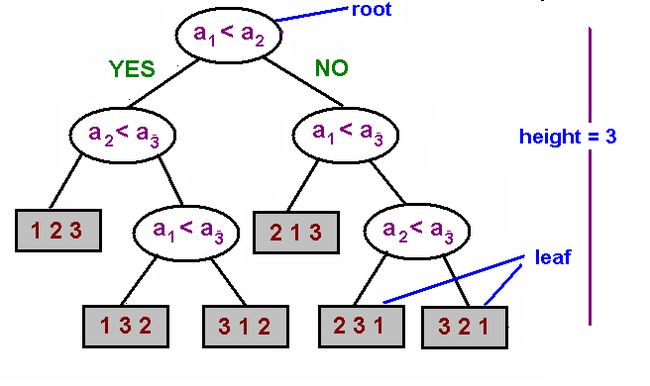

Next, we observe that each comparison cut down the number of all possible comparisons by a factor 2. Any comparison sorting algorithm can always be put in the form of a decision tree. And conversely, a tree like this can be used as a sorting algorithm. This figure illustrates sorting a list of {a1, a2, a3} in the form of a dedcision tree:

Observe, that the worst case number of comparisons made by an algorithm is just the longest path in the tree. At each leaf in the tree, no more comparisons to be made. Therefore, the number of leaves cannot be more than 2x, where x is the maximum number of comparisons (or the longest path in the tree). On the other hand, as we counded in the previous paragraph, the number of all possible permutatioins is n!. Combining these two facts, gives us the following equality:

2x ≥ N!

where x is the number of comparisons. By taking logarithm, implies

x ≥ log N!

Using the Stirling formula for N!, we finally arrive at

x ≥ N log N

or

x = O(N Log N)

Sorting in Java

In this section we discuss four different ways to sort data in Java.

Arrays of primitives

An array of primitives is sorted by direct invocation of Arrays.sort method

int[] a1 = {3,4,1,5,2,6};

Arrays.sort(a1);

Arrays of objects

In order to sort an array of abstract object, we have to make sure that objects are mutually comparable. The idea of comparable is extension of equals in a sence than we need to know not only that two objects are not equal but which one is larger or smaller. This is supported by the Comparable interface. This interface contains only one method with the following signature:

public int compareTo(Object obj);

The returned value is negative, zero or positive depending on whether this object is less, equals or greater than parameter object. Note a difference between the equals() and compareTo() methods. In the following code example we design a class of playing cards that can be compared based on their values:

class Card implements Comparable{ private String suit; private int value; public Card(String suit, int value) { this.suit = suit; this.value = value; } public int getValue() { return value; } public String getSuit() { return suit; } public int compareTo(Card x) { return getValue() - x.getValue(); } }

Suppose that the Card class implements the Comparable interface, then we can sort a group of cards by envoking by Arrays.sort method.

Card[] hand = new Card[5]; Random rand = new Random(); for (int i = 0; i ‹ 5; i++) hand[i] = new Card(rand.nextInt(5), rand.nextInt(12)); Arrays.sort(hand);

It is important to recognize that if a class implements the Comparable interface than compareTo() and equals() methods must be correlated in a sense that if x.compareTo(y)==0, then x.equals(y)==true. The default equals() method compares two objects based on their reference numbers and therefore in the above code example two cards with the same value won't be equal. And a final comment, if the equals() method is overriden than the hashCode() method must also be overriden, in order to maintain the following properety: if x.equals(y)==true, then x.hashCode()==y.hashCode().

Collection of comparable objects

Mutually comparable objects in a collection are sorted by Collections.sort method:

ArrayList‹Integer> a2 = new ArrayList‹Integer> (5); ... Collections.sort(a2);

Comparator

The Comparable interface does not provide a complete solution. The main problem is that the above code works only for objects that have that particular implementation of the compareTo method. Once you implemented compareTo , you don't have much flexibility. Moreover, it is not always possible to decide on a "correct" meaning for compareTo. This method can be based on many different ideas. The solution to this problem is to pass the comparison function as a parameter. Such comparison function in Java is implemented as the Comparator interface. Consider a poker hand: to do a fast evaluation you want to sort your cards either by value or by suit. The way to support these two different criterias is to create two classes SortByValue and SortBySuit that implements Comparator interface

class SuitSort implements Comparator

{

public int compare(Object x, Object y)

{

int a = ((Card) x).getSuit();

int b = ((Card) y).getSuit();

return a-b;

}

}

and then pass a comparison function into a sorting routine. In Java, you cannot pass a method; you should wrap a class around it.

Arrays.sort(hand, new SuitSort());

This new object SuitSort is called a functor, and the style of programming is called a functional programming. The functor is a simple class which usually contains no data, but only a single method. We can design different comparison functions by simply declaring new classes, one class for each kind of functionality. An instance of this class (which implements the interface) is passed to algorithm, which in turn calls the method from the function object.

转自:https://www.cs.cmu.edu/~adamchik/15-121/lectures/Sorting%20Algorithms/sorting.html