Chapter8

Analyzing Sentence Structure 分析句子结构

Earlier chapters focused on words: how to identify them, analyze their structure, assign them to lexical categories, and access their meanings. We have also seen how to identify patterns in word sequences or n-grams. However, these methods only scratch the surface of the complex constraints that govern sentences. We need a way to deal with the ambiguity that natural language is famous for. We also need to be able to cope with the fact that there are an unlimited number of possible sentences, and we can only write finite programs to analyze their structures and discover their meanings.

The goal of this chapter is to answer the following questions:

- How can we use a formal grammar to describe the structure of an unlimited set of sentences?

我们如何使用形式化语法来描述句子的无限制集的结构?

- How do we represent the structure of sentences using syntax trees?

我们如何使用句法树来表示句子结构?

- How do parsers analyze a sentence and automatically build a syntax tree?

语法分析器如何分析一个句子并且自动地构建一个语法树?

Along the way, we will cover the fundamentals of English syntax, and see that there are systematic aspects of meaning that are much easier to capture once we have identified the structure of sentences.

8.1 Some Grammatical Dilemmas 一些语法困境

Linguistic Data and Unlimited Possibilities 语言数据和无限可能

Previous chapters have shown you how to process and analyse text corpora, and we have stressed the challenges for NLP in dealing with the vast amount of electronic language data that is growing daily. Let's consider this data more closely, and make the thought experiment that we have a gigantic(巨大的) corpus consisting of everything that has been either uttered(完全) or written in English over, say, the last 50 years. Would we be justified in calling this corpus "the language of modern English"? There are a number of reasons why we might answer No. Recall that in Chapter 3, we asked you to search the web for instances of the pattern the of. Although it is easy to find examples on the web containing this word sequence, such as New man at the of IMG (http://www.telegraph.co.uk/sport/2387900/New-man-at-the-of-IMG.html), speakers of English will say that most such examples are errors, and therefore not part of English after all.

Accordingly, we can argue that the "modern English" is not equivalent to the very big set of word sequences in our imaginary corpus. Speakers of English can make judgements about these sequences, and will reject some of them as being ungrammatical(不合文法的).

Equally, it is easy to compose a new sentence and have speakers agree that it is perfectly good English. For example, sentences have an interesting property that they can be embedded inside larger sentences. Consider the following sentences:

| (1) |

|

|

If we replaced whole sentences with the symbol S, we would see patterns like Andre said S and I think S. These are templates for taking a sentence and constructing a bigger sentence. There are other templates we can use, like S but S, and S when S. With a bit of ingenuity(独创性) we can construct some really long sentences using these templates. Here's an impressive example from a Winnie the Pooh story by A.A. Milne, In which Piglet is Entirely Surrounded by Water:

[You can imagine Piglet's joy when at last the ship came in sight of him.] In after-years he liked to think that he had been in Very Great Danger during the Terrible Flood, but the only danger he had really been in was the last half-hour of his imprisonment, when Owl, who had just flown up, sat on a branch of his tree to comfort him, and told him a very long story about an aunt who had once laid a seagull's egg by mistake, and the story went on and on, rather like this sentence, until Piglet who was listening out of his window without much hope, went to sleep quietly and naturally, slipping slowly out of the window towards the water until he was only hanging on by his toes, at which moment, luckily, a sudden loud squawk from Owl, which was really part of the story, being what his aunt said, woke the Piglet up and just gave him time to jerk himself back into safety and say, "How interesting, and did she?" when — well, you can imagine his joy when at last he saw the good ship, Brain of Pooh (Captain, C. Robin; 1st Mate, P. Bear) coming over the sea to rescue him...

This long sentence actually has a simple structure that begins S but S when S. We can see from this example that language provides us with constructions which seem to allow us to extend sentences indefinitely. It is also striking that we can understand sentences of arbitrary length that we've never heard before: it's not hard to concoct(混合构造) an entirely novel sentence, one that has probably never been used before in the history of the language, yet all speakers of the language will understand it.

The purpose of a grammar is to give an explicit description of a language. But the way in which we think of a grammar is closely intertwined with what we consider to be a language. Is it a large but finite set of observed utterances and written texts? Is it something more abstract like the implicit knowledge that competent speakers have about grammatical sentences? Or is it some combination of the two? We won't take a stand on this issue, but instead will introduce the main approaches.

In this chapter, we will adopt the formal framework of "generative grammar", in which a "language" is considered to be nothing more than an enormous collection of all grammatical sentences, and a grammar is a formal notation that can be used for "generating" the members of this set. Grammars use recursive productions of the form S → S and S, as we will explore in Section 8.3. In Chapter 10 we will extend this, to automatically build up the meaning of a sentence out of the meanings of its parts.

Ubiquitous Ambiguity 普遍存在的歧义性

A well-known example of ambiguity is shown in (2), from the Groucho Marx movie, Animal Crackers (1930):

| (2) |

|

While hunting in Africa, I shot an elephant in my pajamas. How an elephant got into my pajamas I'll never know. |

Let's take a closer look at the ambiguity in the phrase: I shot an elephant in my pajamas. First we need to define a simple grammar:

|

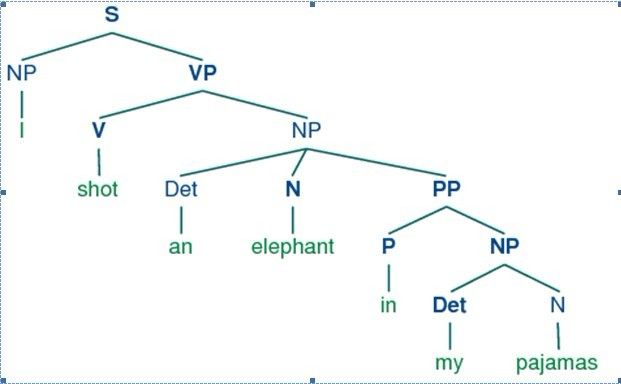

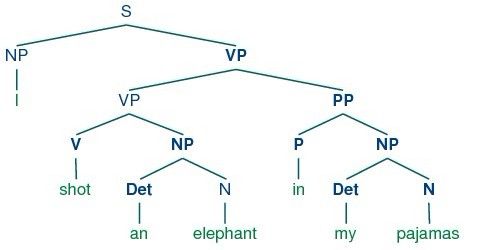

This grammar permits the sentence to be analyzed in two ways, depending on whether the prepositional phrase in my pajamas describes the elephant or the shooting event.

|

The program produces two bracketed structures, which we can depict as trees, as shown in (3b):

| (3) |

|

|

Notice that there's no ambiguity concerning the meaning of any of the words; e.g. the word shot doesn't refer to the act of using a gun in the first sentence, and using a camera in the second sentence.

Note

Your Turn: Consider the following sentences and see if you can think of two quite different interpretations: Fighting animals could be dangerous. Visiting relatives can be tiresome. Is ambiguity of the individual words to blame? If not, what is the cause of the ambiguity?

This chapter presents grammars and parsing, as the formal and computational methods for investigating and modeling the linguistic phenomena we have been discussing. As we shall see, patterns of well-formedness and ill-formedness in a sequence of words can be understood with respect to the phrase structure and dependencies. We can develop formal models of these structures using grammars and parsers. As before, a key motivation is natural language understanding. How much more of the meaning of a text can we access when we can reliably recognize the linguistic structures it contains? Having read in a text, can a program "understand" it enough to be able to answer simple questions about "what happened" or "who did what to whom"? Also as before, we will develop simple programs to process annotated corpora and perform useful tasks.