彻底讲清楚Python的Pip 与 Virtualenv

Virtualenv简介

Virtualenv solves this problem by creating a completely isolated virtual environment for each of your programs.

An environment is simply a directory that contains a complete copy of everything needed to run a Python program, including a copy of the python binary itself, a copy of the entire Python standard library, a copy of the pip installer, and (crucially) a copy of the site-packages directory mentioned above.

When you install a package from PyPI using the copy of pip that’s created by the virtualenv tool, it will install the package into the site-packages directory inside the virtualenv directory. You can then use it in your program just as before.

安装

pip install virtualenv生成虚拟环境

默认

默认是python2那么生成的环境就是python2的,默认是python3那么生成的环境就是python3的

virtualenv defaultpython3+pip3

virtualenv -p python3 py3-envpython2+pip2

virtualenv -p python2 py2-env切换进入虚拟环境

# source bin目录下的activate的文件

source name_env/bin/activate推出虚拟环境

deactivateA non-magical introduction to Pip and Virtualenv for Python beginners

One of the hurdles that new Python developers have to get over is understanding the Python packaging ecosystem. This blog post attempts to explain pip and virtualenv for new Python users.

- Overview

- pip

- virtualenv

- What problem does it solve?

- How does virtualenv help

- How can I install virtualenv

- How do I create a new virtual environment?

- How do I use my shiny new virtual environment?

- But that’s a lot of typing!

- Requirements files

Overview

- pip is a tool for installing packages from the Python Package Index.

- virtualenv is a tool for creating isolated Python environments containing their own copy of python, pip, and their own place to keep libraries installed from PyPI (Python Package Index).

- It’s designed to allow you to work on multiple projects with different dependencies at the same time on the same machine.

- You can see instructions for installing it at virtualenv.org.

- After installing it, run virtualenv envx_for_projectx to create a new environment inside a directory called envx_for_projectx.

- You’ll need one of these environments for each of your projects. Make sure you exclude these directories from your version control system.

- To use the versions of python and pip inside the environment, type env/bin/python and env/bin/pip respectively.

- You can “activate” an environment with source env/bin/activate and deactivate one with deactivate. This is entirely optional but might make life a little easier.

Pip

Let’s dive in. pip is a tool for installing Python packages from the Python Package Index. Python actually has another, more primitive, package manager called easy_install, which is installed automatically when you install Python itself. (其实从Python3.4开始,pip已经被包含到标准Python中)

pip is vastly superior to easy_install for lots of reasons, and so should generally be used instead. pip的优势

对于较低版本的python,可以通过easy_install去安装pip包:

$ sudo easy_install pipYou can then install packages with pip as follows (in this example, we’re installing Django):

# DON'T DO THIS

$ sudo pip install djangoHere, we’re installing Django globally on the system. But in most cases, you shouldn’t install packages globally. Read on to find out why.

Virtualenv

Virtualenv solves a very specific problem: it allows multiple Python projects that have different (and often conflicting) requirements, to coexist on the same computer.

What problem does it solve?

To illustrate this, let’s start by pretending virtualenv doesn’t exist. Imagine we’re going to write a Python program that needs to make HTTP requests to a remote web server. We’re going to use the Requests library, which is brilliant for that sort of thing. As we saw above, we can use pip to install Requests.

But where on your computer does pip install the packages to? (通过pip安装的包到底放在了哪里?) Here’s what happens if I try to run pip install requests:

$ pip install requests

Downloading/unpacking requests

Downloading requests-1.1.0.tar.gz (337Kb): 337Kb downloaded

Running setup.py egg_info for package requests

Installing collected packages: requests

Running setup.py install for requests

error: could not create '/Library/Python/2.7/site-packages/requests': Permission deniedOops! It looks like pip is trying to install the package into /Library/Python/2.7/site-packages/requests. This is a special directory that Python knows about. Anything that’s installed in site-packages can be imported by your programs.

We’re seeing the error because /Library/ (on a Mac) is not usually writeable by “ordinary” users. To fix the error, we can run sudo pip install requests (sudo means “run this command as a superuser”就是管理员模式). Then everything will work fine:

$ sudo pip install requests

Password:

Downloading/unpacking requests

Running setup.py egg_info for package requests

Installing collected packages: requests

Running setup.py install for requests

Successfully installed requests

Cleaning up...This time it worked. We can now type python and try importing our new library:

>>> import requests

>>> requests.get('http://dabapps.com')

200]> So, we now know that we can import requests and use it in our program. We go ahead and work feverishly on our new program, using requests (and probably lots of other libraries from PyPI too). The software works brilliantly, we make loads of money, and our clients are so impressed that they ask us to write another program to do something slightly different.

But this time, we find a brand new feature that’s been added to requests since we wrote our first program that we really need to use in our second program. So we decide to upgrade the requests library to get the new feature:

sudo pip install --upgrade requestsEverything seems fine, but we’ve unknowingly created a disaster!

Next time we try to run it, we discover that our original program (the one that made us loads of money) has completely stopped working and is raising errors when we try to run it. Why? Because something in the API of the requests library has changed between the previous version and the one we just upgraded to. It might only be a small change, but it means our code no longer uses the library correctly. Everything is broken!

Sure, we could fix the code in our first program to use the new version of the requests API, but that takes time and distracts us from our new project. And, of course, a seasoned Python programmer won’t just have two projects but dozens - and each project might have dozens of dependencies! Keeping them all up-to-date and working with the same versions of every library would be a complete nightmare.

How does virtualenv help?

Virtualenv solves this problem by creating a completely isolated virtual environment for each of your programs. An environment is simply a directory that contains a complete copy of everything needed to run a Python program, including a copy of the python binary itself, a copy of the entire Python standard library, a copy of the pip installer, and (crucially) a copy of the site-packages directory mentioned above.

When you install a package from PyPI using the copy of pip that’s created by the virtualenv tool, it will install the package into the site-packages directory inside the virtualenv directory. You can then use it in your program just as before.

How can I install virtualenv?

If you already have pip, the easiest way is to install it globally sudo pip install virtualenv.

Usually pip and virtualenv are the only two packages you ever need to install globally, because once you’ve got both of these you can do all your work inside virtual environments.

How do I create a new virtual environment?

You only need the virtualenv tool itself when you want to create a new environment. This is really simple. Start by changing directory into the root of your project directory, and then use the virtualenv command-line tool to create a new environment:

$ cd ~/code/myproject/

$ virtualenv env

New python executable in env/bin/python

Installing setuptools............done.

Installing pip...............done.Here, env is just the name of the directory you want to create your virtual environment inside. It’s a common convention to call this directory env, and to put it inside your project directory (so, say you keep your code at ~/code/projectname/, the environment will be at ~/code/projectname/env/ - each project gets its own env). But you can call it whatever you like and put it wherever you like!

Note: if you’re using a version control system like git, you shouldn’t commit the env directory. Add it to your .gitignore file (or similar).这样有什么问题,如何解决

How do I use my shiny new virtual environment?

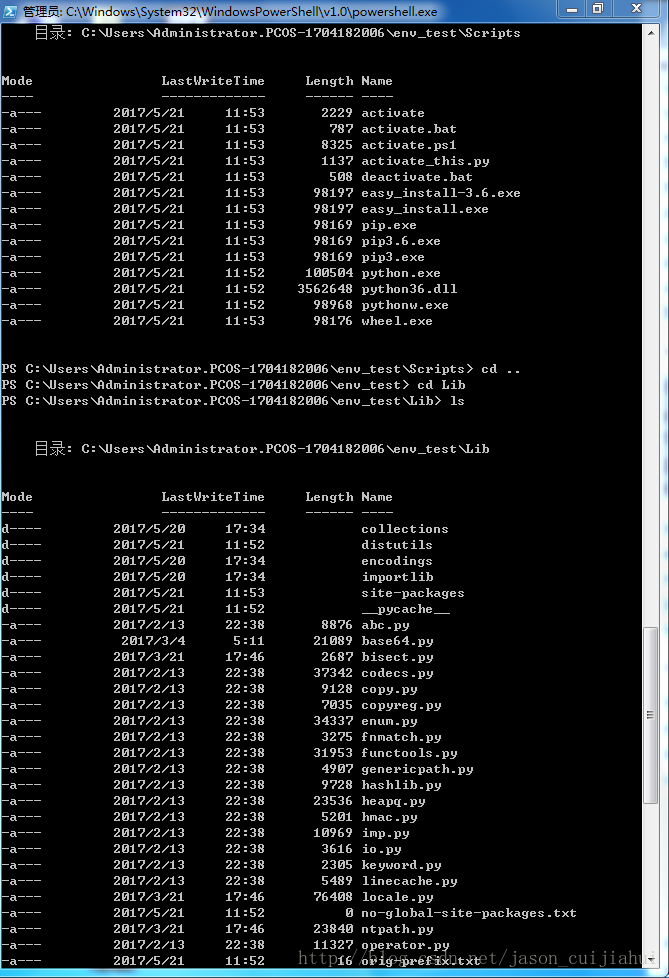

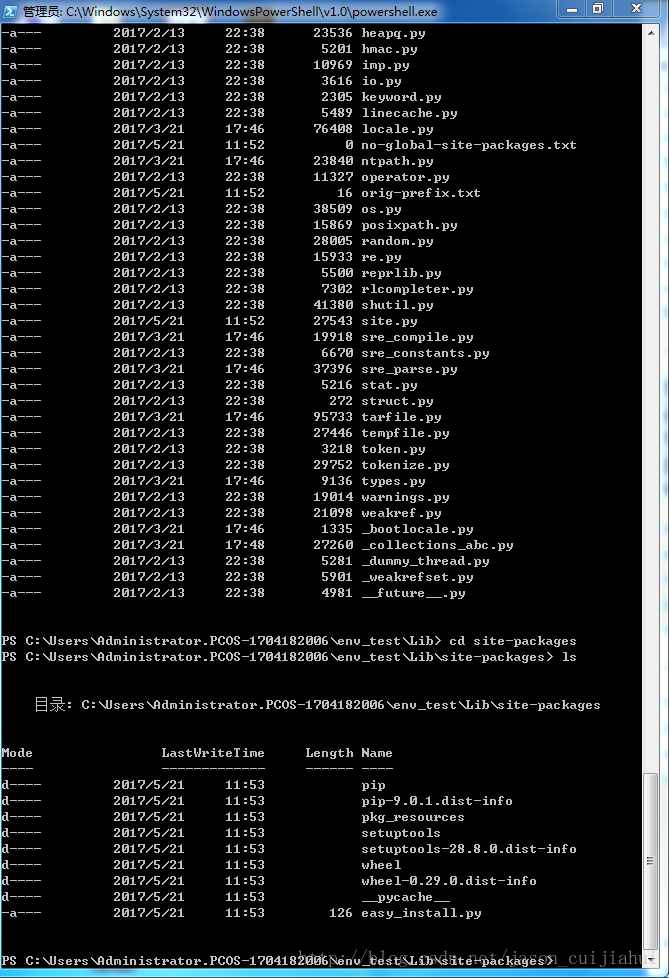

If you look inside the env directory you just created, you’ll see a few subdirectories:

$ ls env

bin include libThe one you care about the most is bin. This is where the local copy of the python binary and the pip installer exists. (Windows的cmd/Powershell上是Scripts)

Let’s start by using the copy of pip to install requests into the virtualenv (rather than globally):

$ env/bin/pip install requests

Downloading/unpacking requests

Downloading requests-1.1.0.tar.gz (337kB): 337kB downloaded

Running setup.py egg_info for package requests

Installing collected packages: requests

Running setup.py install for requests

Successfully installed requests

Cleaning up...It worked! Notice that we didn’t need to use sudo this time, because we’re not installing requests globally, we’re just installing it inside our home directory.

Now, instead of typing python to get a Python shell, we type env/bin/python, and then…

>>> import requests

>>> requests.get('http://dabapps.com')

200]> But that’s a lot of typing!

virtualenv has one more trick up its sleeve. (因为每次都要env/bin/python或env/bin/pip太不简洁了,后面就是解决方法)Instead of typing env/bin/python and env/bin/pip every time, we can run a script to activate the environment.

This script, which can be executed with source env/bin/activate(该脚本就在env/bin目录下,运行后把python的默认路径改变为…/env/bin/python下), simply adjusts a few variables in your shell (temporarily) so that when you type python, you actually get the Python binary inside the virtualenv instead of the global one:

$ which python

/usr/bin/python

$ source env/bin/activate

$ which python

/Users/jamie/code/myproject/env/bin/pythonSo now we can just run pip install requests (instead of env/bin/pip install requests) and pip will install the library into the environment, instead of globally.

The adjustments to your shell only last for as long as the terminal is open, so you’ll need to remember to rerun source env/bin/activate each time you close and open your terminal window.

If you switch to work on a different project (with its own environment) you can run deactivate to stop using one environment, and then source env/bin/activate to activate the other.

Activating and deactivating environments does save a little typing, but it’s a bit “magical” and can be confusing. Make your own decision about whether you want to use it.

Requirements files

virtualenv and pip make great companions, especially when you use the requirements feature of pip. Each project you work on has its own requirements.txt file, and you can use this to install the dependencies for that project into its virtual environment: (导入虚拟环境配置)

env/bin/pip install -r requirements.txt关于导出、导入虚拟环境的配置的资料,这也关于版本控制时不上传env文件夹,则如何上传配置的解决方法