目录

- 8.1 过程型程序设计进阶

- 8.1.1 使用字典进行分支

- 8.1.2 生成器表达式与函数

- 8.1.3 动态代码执行与动态导入

- 动态程序设计与内省函数(表)

- Tips type(obj)(name)

- 8.1.4 局部函数与递归函数

- 8.1.5 函数与方法修饰器

- 8.1.6 函数注释

- 8.2 面向对象程序设计进阶

- __slots__

- 8.2.1 控制属性存储

- 用于属性存取的特殊方法

- 8.2.2 函子

- 8.2.3 上下文管理器 with

- 8.2.4 描述符_get_,__set__,__delete__ (书本在此处有误)

- 8.2.5 类修饰器

- 8.2.6 抽象基类

- 8.2.7 多继承

- 8.2.8 元类

- 8.3 函数型程序设计

- map, filter, reduce

- 8.3.1 偏函数

- 8.3.2 协程

- 8.4 实例:Valid

《Python 3 程序开发指南》学习笔记

8.1 过程型程序设计进阶

8.1.1 使用字典进行分支

如果我们希望编写一个交互式程序,提供了option1~option5这5个选项,不同的选项对应不同的操作。一种较为繁琐的操作是是通过\(if...elif...\)来实现。更为简便的方法是,通过字典进行分支,因为函数,如果不加(),那么也是可以作为变量来进行传递的。隐式地表达函数,再加之( ),也可以运行函数。

def f1(x): pass

def f2(x): pass

def f3(x): pass

def f4(x): pass

def f5(x): pass

functions = dict(option1=f1, option2=f2,

option3=f3, option4=f4,

option5=f5)

option = "option2"

x = "参数"

functions[option](x)8.1.2 生成器表达式与函数

创建生成器表达式与列表内涵几乎等同,区别是变成了圆括号:

(expression for item in iterable)

(expression for item in iterable if condtion)d = dict(a=1, b=2, c=3, d=4)

def items_in_key_order(d):

return ((key, d[key])

for key in sorted(d))这种方式生成是生成器,比较熟悉的方式是:

def items_in_key_order(d):

for key in sorted(d):

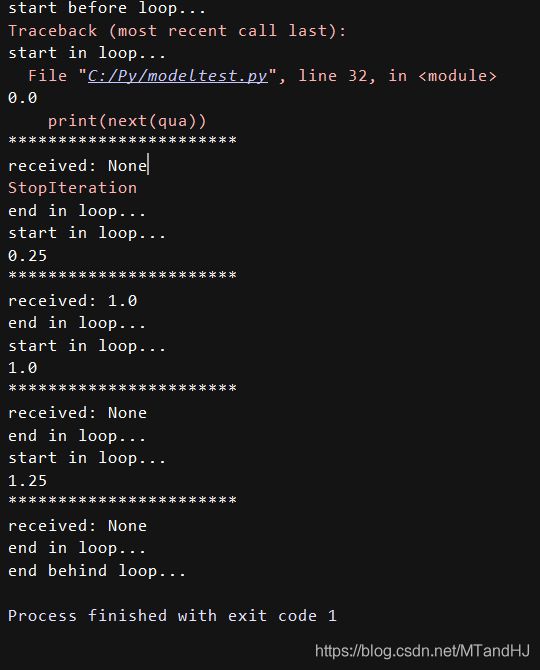

yield key, d[key]def quarters(next_quarter=0.0):

print("start before loop...")

while next_quarter < 1.5:

print("start in loop...")

received = (yield next_quarter)

print("received:", received)

if received is None:

next_quarter += 0.25

else:

next_quarter = received

print("end in loop...")

print("end behind loop...")

qua = quarters()

print(next(qua))

print("***********************")

print(next(qua))

print("***********************")

print(qua.send(1.0))

print("***********************")

print(next(qua))

print("***********************")

print(next(qua))

print("***********************")从上面的结果可以看出,yield是这样的。qua = quarters()部分语句并没有执行函数(特别执行?)。next(qua),函数会执行到yield部分,停下,但是并没有传递值给received。再次执行next(qua),函数会从上次的yield部分继续执行,转一圈回到yield部分。qua.send(1.0)把这个值传递给received,然后接着执行余下的部分。这种类似的操作会一直持续到生成器结束,然后产生一个StopIteration错误。我们可以通过generator.close()来提前关闭。

8.1.3 动态代码执行与动态导入

动态程序设计与内省函数(表)

| 语法 | 描述 |

|---|---|

| __import__ | 根据模块名导入模块 |

| compile(source, file, mode) | 返回编译source文本生成的代码对象,这里,file应该是文件名,或" |

| delattr(obj, name) | 从对象obj中删除名为name的属性 |

| dir(obj) | 返回本地范围内的名称列表,或者,如果给定obj,就返回obj的名称(比如,其属性和方法) |

| eval(source, globals, locals) | 返回对source中单一表达式进行评估的结果,如果提供,那么globals表示的是全局上下文,locals表示的是本地上下文(作为字典) |

| exec(obj, globals, locals) | 对对象obj进行评估,该对象可以是一个字符串,也可以是来自compile()的代码对象,返回则为None;如果提供,那么globals表示的是全局上下文,locals表示的是本地上下文 |

| getattr(obj, name, val) | 返回对象obj中名为name的属性值,如果没有这一属性,并且给定了val参数,就返回val |

| globals() | 返回当前全局上下文的字典 |

| hasattr(obj, name) | 如果对象obj中名为name的属性,就返回True |

| locals() | 返回当前本地上下文的字典 |

| setattr(obj, name, val) | 将对象obj中名为name的属性值设为val,必要的时候创建该属性 |

| type(obj) | 返回该对象obj的类型对象 |

| vars(obj) | 以字典形式返回对象obj的上下文,如果没有给定obj,就返回本地上下文 |

动态代码执行 eval(), exec()

eval, exec, compile-明王不动心

eval()能够执行内部的字符串表达式。

eval()-linux运维菜

eval()-大大的橙子

x = eval("(2 ** 31) - 1") # x == 2147483647我们也可以利用exec()来构建函数,动态导入模块等,同样的,第二个参数我们可以提供全局参数,第二个参数我们可以提供本地参数。

import math

code = '''

def area_of_sphere(r):

return 4 * math.pi * r ** 2

'''

context = {}

context["math"] = math

a = exec(code, context)

print(a) #None

area_of_sphere = context["area_of_sphere"]

print(area_of_sphere(10)) #1256.6370614359173动态导入模块

我们将查看三种等价的动态导入模块的方法。

import os

import sys

def load_modules():

"""第一种方法,也是最复杂的一种"""

modules = []

for name in os.listdir(os.path.dirname(__file__) or "."):

"""__file__ 当前目录, 为了避免为空所以加了\".\""""

if name.endswith(".py") and "magic" in name.lower():

"""我们选择带有magic的模块"""

filename = name

name = os.path.splitext(name)[0] #剥离扩展名

if name.isidentifier() and name not in sys.modules:

"""有效标识符且为模块的才被选择"""

fh = None

try:

fh = open(filename, "r", encoding="utf8")

code = fh.read() #读取代码

module = type(sys)(name) #!!!超牛

sys.modules[name] = module#加入模块

exec(code, module.__dict__)#执行代码,并将创建的东西加入到模块中

modules.append(module)#捕获到一个模块

except (EnvironmentError, SyntaxError) as err:

sys.modules.pop(name, None)

print(err)

finally:

if fh is not None:

fh.close()第二种方法,只需要上面的一段代码就可以了。

try:

exec("import " + name)

modules.append(sys.modules[name])#捕获到一个模块

except (SyntaxError) as err:

print(err)第三种方法使用了_import_:

try:

module = __import__(name)

modules.append(sys.modules[name])#捕获到一个模块

except (ImportError ,SyntaxError) as err:

print(err)接下来,通过Python内置的自省函数getattr()与hasattr()来访问模块中提供的功能:

def get_function(module, function_name):

function = get_function.cache.get((module, function_name), None)

"""

当第一次执行的时候,一定是None,之后每当遇到合适的函数,就会

保存到get_function.cache当中,这可以避免二次回访该函数带来的

消耗

"""

if function is None:

try:

function = getattr(module, function_name)

if not hasattr(function, "__call__"):

raise AttributeError()

get_function.cache[module, function_name] = function

except AttributeError:

function = None

return function

get_function.cache = {}Tips type(obj)(name)

我们可以利用type(obj)(name)的方式巧妙地创建对象。

a = 1

b = ""

print(type(a)) #

print(type(a)(2)) # 2

print(type(b)) #

print(type(b)('d')) # d 8.1.4 局部函数与递归函数

递归函数可能消耗大量的计算资源,因为每次递归调用,都会使用另一个栈帧(函数执行的环境,大概这个意思)。然而,有些算法使用递归进行描述是最自然的。大多数Python实现都对可以进行多少次递归调用有一个固定的限制值,这一数值可由sys.getrecursionlimit()函数返回,也可由sys.setrecursionlimit()函数进行设置。但要求增加这一数值通常表明使用的算法不适当,或实现中有bug。

sys.getrecursionlimit() # 3000一个递归的例子:阶乘计算。

def factorial(x):

if x <= 1:

return 1

return x * factorial(x-1)

print(factorial(10)) #3628800下面,我们再给出一个关于排序的例子。目录,根据标题的级别会有缩排,假设标题的缩排已经完成,标题的顺序是乱的(但是子标题的归属不乱,乱的只是子标题之间的序),具体的情况看代码中的before。indented_list_sort函数对其进行了重排。

def indented_list_sort(indented_list, indent=" "):

"""重排"""

KEY, ITEM, CHILDREN = range(3) #为索引位置提供名称

def add_entry(level, key, item, children):

"""父元素下添加子元素"""

if level == 0:

children.append((key, item, []))

else:

add_entry(level-1, key, item, children[-1][CHILDREN])

def update_indented_list(entry):

"""对每一顶级条目,该函数向indented.list中添加

一项,之后对每一项的孩子条目调用自身。

"""

indented_list.append(entry[ITEM])

for subentry in sorted(entry[CHILDREN]):

update_indented_list(subentry)

entries = []

for item in indented_list:

level = 0

i = 0

while item.startswith(indent, i): #给item评级

i += len(indent)

level += 1

key = item.strip().lower() #key是item的一个小写副本,用来排序

add_entry(level, key, item, entries)

indented_list = []

for entry in sorted(entries):

update_indented_list(entry)

return indented_list

before = [

"第六章 面向对象程序设计",

" 6.1 面向对象方法",

" 6.4 总结",

" 6.3 自定义组合类",

" 6.3.1 创建聚集组合数据的类",

" 6.3.2 使用聚集创建组合类",

" 6.3.3 使用继承创建组合类",

" 6.5 练习",

" 6.2 自定义类",

" 6.2.2 继承与多态",

" 6.2.1 属性与方法",

" 6.2.4 创建完全整合的数据类型",

" 6.2.3 使用特性进行属性的存取控制"

]

after = indented_list_sort(before)

for item in after:

print(item)重排后的为:

第六章 面向对象程序设计

6.1 面向对象方法

6.2 自定义类

6.2.1 属性与方法

6.2.2 继承与多态

6.2.3 使用特性进行属性的存取控制

6.2.4 创建完全整合的数据类型

6.3 自定义组合类

6.3.1 创建聚集组合数据的类

6.3.2 使用聚集创建组合类

6.3.3 使用继承创建组合类

6.4 总结

6.5 练习8.1.5 函数与方法修饰器

修饰器是一个函数,接受一个函数或方法作为其唯一的参数,并返回一个新函数或方法,其中整合了修饰后的函数或方法,并附带了一些额外附加的功能。我们已经用过一些预定义的修饰器,如@property与@classmethod。

下面这个例子,我们希望,函数的结果是非负的,否则就报错,利用修饰器可以完成这一任务(虽然这项工作只需要在原函数内部加一个断言就能完成,但这种方式有更好的泛化性和可读性)。

def positive_result(function):

"""这个玩意儿在使用positive_result之前的地方创建?"""

def wrapper(*args, **kwargs):

result = function(*args, **kwargs)

assert result >=0, function.__name__ + "() result isn't >= 0"

return result

wrapper.__name__ = function.__name__

wrapper.__doc__ = function.__doc__

return wrapper

@positive_result

def discriminant(a, b, c):

return (b ** 2) - (4 * a *c)修饰器的作用好像就是f = decorate(f),下面是我的一些小测试:

def decorate(function):

def wrapper(*args, **kwargs):

result = function(*args, **kwargs)

return result

return wrapper

@decorate

def f(x):

print("How to love the world?")

return 1

def f2(x):

print("I'm the death!")

def f3(x):

print("Show me the fire!")

print(f.__name__) # wrapper

newf = decorate(f2)

print(newf.__name__) # wrapper

print(newf is f) # False

newf(1) # I'm the death!

f2 = f3

newf(1) # I'm the death我以为f2=f3之后函数是会变的,结果是不变的,这个结果自然是好的,但我逻辑上总不知道怎么过去。我不知道是怎么实现的。

下面是更为纯净的版本,使用了functools的版本

import functools

def positive_result(function):

"""更为纯净的版本"""

@functools.wraps(function)

def wrapper(*args, **kwargs):

result = function(*args, **kwargs)

assert result >=0, function.__name__ + "() result isn't >= 0"

return result

return wrapper

@positive_result

def discriminant(a, b, c):

return (b ** 2) - (4 * a *c)

print(discriminant.__name__, discriminant.__doc__)上面functools.wraps的工作是更新wrapper的__name__和__doc__属性,值得注意的是,这个修饰器是带参数的修饰器。

下面是个人对这个方法的一个尝试,但是效果是一样的。

def wraps(function1):

def decorator(function2):

def wrapper(*arg, **kwargs):

return function2(*arg, **kwargs)

wrapper.__name__ = function1.__name__

wrapper.__doc__ = function1.__doc__

return wrapper

return decorator

def positive_result(function):

@wraps(function)

def wrapper(*args, **kwargs):

result = function(*args, **kwargs)

assert result >=0, function.__name__ + "() result isn't >= 0"

return result

return wrapper

@positive_result

def discriminant(a, b, c):

return (b ** 2) - (4 * a *c)

print(discriminant.__name__, discriminant.__doc__)

print(discriminant(1, 4, 3))同样的,不要在意我们另外创建一个函数,显得麻烦,这是泛化的代价。我对@wraps(function)这个语句的猜测是:

@wraps(function)

def f(*args, **kwargs): pass

等价于:

f = wraps(function)(f)

这么看可能还是有点抽象,Python应该是把@后面的当成一个函数,所以wraps(function)会先运行,然后返回decorator,这是一个函数对象,所以wraps实际上并不是真正的修饰器。

再来看一个例子:

import functools

def bounded(minimum, maximum):

"""这个函数用来界定函数值"""

def decorator(function):

"""这部分才是真正的修饰器"""

@functools.wraps(function)

def wrapper(*args, **kwargs):

result = function(*args, **kwargs)

if result > maximum:

return maximum

elif result < minimum:

return minimum

else:

return result

return wrapper

return decorator

@bounded(0, 100)

def percent(amount, total):

return (amount / total) * 100

print(percent(20, 2)) #100本小节,我们将创建的最后一个修饰器较为复杂一些,是一个记录函数,记录其修饰的任何函数的名称、参数与结果。

import functools, logging, tempfile, os

if __debug__:#在调试模式下,全局变量__debug__为True

logger = logging.getLogger("Logger") #logging模块

logger.setLevel(logging.DEBUG)

handler = logging.FileHandler(os.path.join(tempfile.gettempdir(),

"logged.log"))

print(tempfile.gettempdir())

logger.addHandler(handler)

def logged(function):

@functools.wraps(function)

def wrapper(*args, **kwargs):

log = "called: " + function.__name__ + "("

log += ",".join(["{0!r}".format(a) for a in args] +

["{0!s}={1!r}".format(k, v)

for k, v in kwargs.items()])

result = exception = None

try:

result = function(*args, **kwargs)

return result

except Exception as err:

exception = err

finally:

log += (") -> " + str(result) if exception is None

else ") {0}: {1}".format(type(exception),

exception))

logger.debug(log)

if exception is not None:

raise exception

return wrapper

else:

def logged(function):

return function

@logged

def discount_price(price, percentage, make_integer=False):

result = price * ((100 - percentage) / 100)

if not (0 < result <= price):

raise ValueError("invalid price")

return result if not make_integer else int(round(result))

test = [(100, 10),

(210, 5),

(210, 5, True),

(210, 14, True),

(210, -8)]

for item in test:

discount_price(*item)called: discount_price(100,10) -> 90.0

called: discount_price(210,5) -> 199.5

called: discount_price(210,5,True) -> 200

called: discount_price(210,14,True) -> 181

called: discount_price(210,-8)

***

再来一个例子,多重修饰:

def decorate1(function):

print("start decorate1...")

def wrapper(*args, **kwargs):

result = function(*args, **kwargs)

return result

wrapper.__name__ = function.__name__

wrapper.__doc__ = function.__doc__

print("end decorate1...")

return wrapper

def decorate2(function):

print("start decorate2...")

def wrapper(*args, **kwargs):

result = function(*args, **kwargs)

return result

wrapper.__name__ = function.__name__

wrapper.__doc__ = function.__doc__

print("end decorate2...")

return wrapper

@decorate1

@decorate2

def f(x):

print("start f...")

print(x)

print("end f...")

f("MMMMMMM")start decorate2...

end decorate2...

start decorate1...

end decorate1...

start f...

MMMMMMM

end f...

***

8.1.6 函数注释

函数与方法在定义时都可以带有注释——可用在函数签名中的表达式。

def functionName(par1: exp1, par2: exp2, ..., parN: expN) -> rexp:

suite如果存在注释,就会被添加到函数的__annotations__字典中,如果不存在,此字典为空。

def add(num1:"the first number", num2:"the second number") -> "the sum of sum1 and sum2":

return num1 + num2

print(add.__annotations__)

#{'num1': 'the first number', 'num2': 'the second number', 'return': 'the sum of sum1 and sum2'}乍看,这种注释似乎没有什么用,不过,我们可以利用注释进行参数检查。利用修饰器可以很好的完成这一任务。

import inspect

import functools

def strictly_typed(function):

annotations = function.__annotations__ #获取注释

arg_spec = inspect.getfullargspec(function) #返回参数名称

#确保函数中有相应的参数和返回

assert "return" in annotations, "missing type for return value"

for arg in arg_spec.args + arg_spec.kwonlyargs:

assert arg in annotations, ("missing type for parameter" +

arg + "")

@functools.wraps(function)

def wrapper(*args, **kwargs):

for name, arg in (list(zip(arg_spec.args, args)) +

list(kwargs.items())):

assert isinstance(arg, annotations[name]), (

"expected argument '{0}' of {1} got {2}".format(

name, annotations[name], type(arg)

)

)

result = function(*args, **kwargs)

assert isinstance(result, annotations["return"]), (

"expected return of {0} got {1}".format(

annotations["return"], type(result)

)

)

return result

return wrapper

@strictly_typed

def perimeter_triangle(num1:float, num2:float, num3:float) -> float:

assert num1 > 0, "invalid number {0}".format(num1)

assert num2 > 0, "invalid number {0}".format(num2)

assert num3 > 0, "invalid number {0}".format(num3)

assert num1 + num2 + num3 - max([num1, num2, num3]) \

> max([num1, num2, num3]), \

"invalid triangle"

return float(num1 + num2 + num3)

perimeter_triangle(10., 5., 9.)上面给出的例子,用了Inspect模块。这个模块为对象提供了功能强大的内省服务。

8.2 面向对象程序设计进阶

__slots__

class Point:

__slots__ = ("x", "y")

def __init__(self, x=0, y=0):

self.x = x

self.y = y

class Point2:

def __init__(self, x=0, y=0):

self.x = x

self.y = y

p1 = Point(1, 2)

p2 = Point2(1, 2)

print("__dict__" in dir(p1)) #False

print("__dict__" in dir(p2)) #True

print(p2.__dict__) # {'x':1, 'y':2}在创建一个类而没有使用__slots__时,Python会在幕后为每个实例创建一个名为__dict__的私有字典,该字典存放每个实例的数据属性,这也是为什么我们可以从对象中移除属性或向其中添加属性。

如果对于某个对象,我们只需要访问其原始属性,而不需要添加或移除属性,那么可以创建不包含__dict__的类。这可以通过定义一个名为__slots__的类属性实现,其值是一个属性名元组。

p1.z = 2 #AttributeError: 'Point' object has no attribute 'z'注意,是不能添加或者删除属性,但是已有的属性依旧可以修改。

8.2.1 控制属性存储

__getattr__-xybaby

class Ord:

def __init__(self):

self.X = 1

def __getattr__(self, char):

return ord(char)

ord1 = Ord()

print(ord1.X) # 1

print(ord1.Y) # 89

当我们调用ord1.X的时候,因为我们事先定义了这个属性,所以会返回1,但当我们调用ord1.Y的时候,因为没有这个属性,所以Python会尝试_getattr_(ord1, X),不过奇怪的是,难道char的属性只能是字符吗?

class Const:

def __setattr__(self, name, value):

if name in self.__dict__:

raise ValueError("cannot change a const attribute")

self.__dict__[name] = value

def __delattr__(self, name):

if name in self.__dict__:

raise ValueError("cannot delete a const attribute")

raise AttributeError("'{0}' object has no attribute '{1}'".format(

self.__class__.__name__,

name

))

上面的例子,Const类能够一定程度上避免修改和删除,允许添加。

class Const:

def __init__(self):

self.__con4 = 1 #我们设置一个私有属性做试验

def __setattr__(self, name, value):

if name in self.__dict__:

raise ValueError("cannot change a const attribute")

self.__dict__[name] = value

def __delattr__(self, name):

if name in self.__dict__:

raise ValueError("cannot delete a const attribute")

raise AttributeError("'{0}' object has no attribute '{1}'".format(

self.__class__.__name__,

name

))

c = Const()

c.con1 = 1

c.con2 = 2

c.__con3 = 3

print(c.__dict__) # {'_Const__con4': 1, 'con1': 1, 'con2': 2, '__con3': 3}从上面可以看到,私有属性,以_className__attributeName的形式存储。

用于属性存取的特殊方法

| 特殊方法 | 使用 | 描述 |

|---|---|---|

| __delattr__(self, name) | del x.n | 删除对象x的属性 |

| __dir__(self) | dir(x) | 返回x的属性名列表 |

| __getattr__(self, name) | v = x.n | 返回x的n属性值(如果没有直接找到) |

| __getattribute__(self, name) | v = x.n | 返回对象x的n属性 |

| __setattr__(self, name, value) | x.n = v | 将对象x的n属性值设置为v |

在寻找属性(非特殊)时,__getattr__()方法是最后调用的,__getattribute__()方法则是首先调用的。在某些情况下,调用__getattribute__()方法是必要的,甚至是必需的,但是重新实现__getattribute__()方法可能是非常棘手的,重新实现时必须非常潇心,以防止对自身进行递归调用——使用super().__getattribute__()或object.__getattribute__()通常会导致这种情况。此外,由于__getattirbute__()调用需要对每个属性存取都进行,因此,与直接属性存取或使用特性相比,重新实现该方法将降低性能。

__get__, __getattr__, __getattribute__的区别-Vito.K

8.2.2 函子

在计算机科学中,函子是指一个对象,该对象可以像函数一样进行调用,因此,在Python术语中,函子就是另一种类型的函数对象。任何包含了特殊方法_call_()的类都是一个函子。

class Strip:

#函子可以用来维护一些状态信息

def __init__(self, characters):

self.characters = characters

def __call__(self, string):

return string.strip(self.characters)

strip_punctuation = Strip(",.!?")

print(strip_punctuation("Land ahoy!")) #Land ahoy当然,上述的任务用普通的函数也是可以完成的,但是,普通的函数,如果需要存储状态信息,需要进行复杂的处理。

def make_strip_function(characters):

def strip_function(string):

return string.strip(characters)

return strip_function

strip_punctuation = make_strip_function(",.!?")

print(strip_punctuation("Land ahoy!")) #Land ahoy上面使用了闭包的技术,闭包实际上是一个函数或方法,可以捕获一些外部状态信息。

8.2.3 上下文管理器 with

使用上下文管理器可以简化代码,这是通过确保某些操作在特定代码块执行前与执行后再进行来实现的。之所以可以做到,是因为上下文管理器提供了俩个特殊方法,__enter__()与__exit__(),在with语句范围内,Python会对其进行特别处理。在with语句内创建上下文管理器时,其__enter__()方法会自动被调用,在with语句后、上下文管理器作用范围之外时,其__exit__()方法会自动被调用。

使用上下文管理器的语法如下:

with expression as variable:

suiteexpression部分必须是或者必须生成一个上下文管理器,如果制定了可选的as variable部分,那么该变量被设置为对上下文管理器的_enter_()方法返回的对象进行引用。由于上下文管理器保证可以执行其"exit"代码(即使在产生异常的情况下),因此,很多情况下,使用上下文管理器,就不再需要finally语句块。

下面的例子就是打开文件并处理文件的过程,我们不像之前利用finally语句块来确保文件的关闭,因为文件对象是一个上下文管理器。

try:

with open(filename) as fh:

for line in fh:

process(line)

except EnvironmentError as err:

print(err)contextlib模块 3.0

有些时候,我们需要同时使用不止一个上下文管理器,比如:

try:

with open(source) as fin:

with open(target, "w") as fout:

for line in fin:

fout.write(process(line))

except EnvironmentError as err:

print(err)这种方法的缺陷是,会很快地生成大量地缩排,利用contextlib模块可以避免这一问题。

try:

with contextlib.nested(open(source), open(target, "w")) as (

fin, fout):

for line in fin:

...从Python 3.1 开始,这一函数被废弃,因为Python 3.1可以在一个单独地with语句中处理多个上下文管理器。

try:

with open(source) as fin, open(target, "w") as fout:

for line in fin:

...

如果需要创建自定义的上下文管理器,就必须创建一个类,该类必须提供俩个方法:__enter__()与__exit__()。任何时候,将with语句用于该类的实例时,都会调用__enter__()方法,并将其返回值用于as variable (如果没有,就丢掉返回值)。在控制权离开with语句的作用范围时,会调用__exit__()方法(如果有异常发生,就将异常的详细资料作为参数)。

8.2.4 描述符_get_,__set__,__delete__ (书本在此处有误)

描述符也是类,用于为其他类的属性提供访问控制。实现了一个或多个描述符特殊方法(__get__()、__set__()与__delete__())的任何类都可以称为(也可以用作)描述符。

内置的property()与classmethod()函数都是使用描述符实现的。理解描述符的关键是,尽管在类中创建描述符的实例时将其作为一个类属性,但是Python在访问描述符时是通过类的实例进行的。

我们先来看一看下面这个例子。

import xml.sax.saxutils

class XmlShadow:

def __init__(self, attribute_name):

self.attribute_name = attribute_name

def __get__(self, instance, owner=None):

return xml.sax.saxutils.escape(

getattr(instance, self.attribute_name)

)

class Product:

__slots__ = ("__name", "__description", "__price")

name_as_xml = XmlShadow("name")

description_as_xml = XmlShadow("description")

def __init__(self, name, description, price):

self.__name = name

self.description = description

self.price = price

@property

def description(self):

return self.__description

@description.setter

def description(self, description):

self.__description = description

@property

def price(self):

return self.price

@price.setter

def price(self, price):

self.__price = price

@property

def name(self):

return self.__name

product = Product("Chisel <3cm>", "Chisel & cap", 45.25)

print(product.name, product.name_as_xml, product.description_as_xml)

#Chisel <3cm> Chisel <3cm> Chisel & cap结果在代码中注释掉了,如果XmlShadow类没有定义__get__会输出什么呢?

Chisel <3cm> <__main__.XmlShadow object at 0x00000264527EDC18> <__main__.XmlShadow object at 0x0000026452808828>第一种方式,在尝试访问name_as_xml属性时,Python发现Product类有一个使用该名称的描述符,因此可以使用该描述符获取属性的值。Python在调用描述符的_get_()方法,self参数是描述符的实例,instance参数是Product实例,即product的self,owner参数是所有者类。

让我们再修改一下_get_()方法,来看看会发生什么。

def __get__(self, instance, owner=None):

print(instance, owner)

return xml.sax.saxutils.escape(

getattr(instance, self.attribute_name)

)<__main__.Product object at 0x000001A96A35D408>

<__main__.Product object at 0x000001A96A35D408>

Chisel <3cm> Chisel <3cm> Chisel & cap 从上面可以看到,instance即product这个实例,而owner是Product这个类。

我们也可以利用描述符进行缓存操作:

class CachedxmlShadow:

def __init__(self, attribute_name):

self.attribute_name = attribute_name

self.cache = {}

def __get__(self, instance, owner=None):

xml_text = self.cache.get(id(instance))

if xml_text is not None:

return xml_text

return self.cache.setdefault(id(instance),

xml.sax.saxutils.escape((

getattr(instance, self.attribute_name)

)))在上面我们已经见识了_get_(),下面我们再来看看_set_()。

class Point:

__slots__ = () #空元组,可以保证类不会存储任何数据属性

x = ExternalStorage("x")

y = ExternalStorage("y")

def __init__(self, x=0, y=0):

self.x = x

self.y = y

class ExternalStorage:

__slots__ = ("attribute_name")

__storage = {}

def __init__(self, attribute_name):

self.attribute_name = attribute_name

def __set__(self, instance, value):

self.__storage[id(instance), self.attribute_name] = value

def __get__(self, instance, owner=None):

if instance is None:

return self

return self.__storage[id(instance), self.attribute_name]

Point类通过__slots__设置为一个空元组,可以保证类不会存储任何数据属性。在对self.x进行赋值时候(如果没有__set__是不能赋值的),Python发现有一个名为“x”的描述符,因此使用描述符的__set__()方法。ExternalStorage为Point类提供了一个存取的仓库。

下面我们创建一个Property描述符,来模拟内置的property()函数的行为。

class Property:

def __init__(self, getter, setter=None):

print("here?")

self.__getter = getter

self.__setter = setter

self.__name__ = getter.__name__

def __get__(self, instance, owner=None):

print("get...part")

if instance is None:

return self

return self.__getter(instance)

def __set__(self, instance, value):

print("set..part")

if self.__setter is None:

raise AttributeError("'{0}' is read-only".format(

self.__name__

))

return self.__setter(instance, value)

def setter(self, setter):

print("setter...part")

self.__setter = setter

return self.__setter

class NameAndExtension:

def __init__(self, name, extension):

print("init...")

self.__name = name

self.extension = extension

@Property

def name(self):

return self.__name

@Property

def extension(self):

return self.__extension

@extension.setter

def extension(self, extension):

self.__extension = extension

a = NameAndExtension("a", "b")

a.extension = "c"

上面的代码,在执行的时候就会发现有问题,因为set...part并不会出现,这很奇怪,因为self.extension = extension, a.extension = "c"这俩部分代码都应该会触发set...part。事实上,上面的代码的确是错的,错在setter的定义上,正确应当为:

def setter(self, setter):

self.__setter = setter

return self为什么要return self而不是return self.__setter呢。

让我们回到@extension.setter这行语句上,它的实际含义是:

extension = extension.setter(extension)没错,在这行代码运行之前extension是Property的一个实例,运行之后,它成了一个方法,所以我们在运行a.extension = "c"或者self.extension = extension的时候实际上是重新赋值了,并不是给__extension赋值。

如果我们在赋值阶段添加这么一段语句:

self.__extension = "abcde"然后通过a._NameAndExtension__extension调用,会发现输出是"abcde",即便我们试图通过a.extension = "c"来改变它的值(实际上并没有改变)。

8.2.5 类修饰器

就像可以为函数与方法创建修饰器一样,我们也可以为整个类创建修饰器。类修饰器以类对象(class语句的结果)作为参数,并应该返回一个类——通常是其修饰的类的修订版。

我们来看一个类修饰器的例子:

class Util:

def delegate(attribute_name, method_names):

def decorator(cls):

nonlocal attribute_name

if attribute_name.startswith("__"):

attribute_name = "_" + cls.__name__ + attribute_name

for name in method_names:

context = {}

code = """

def function(self, *arg, **kwarg):

print("welcome to {name}")

return self.{attribute_name}.{name}(*arg, **kwarg)

""".format(attribute_name=attribute_name,

name=name)

exec(code, context)

setattr(cls, name,context["function"])

return cls

return decorator

@Util.delegate("__list", ("pop", "__delitem__", "__getitem__",

"__iter__", "__reversed__", "__len__", "__str__"))

class Testlist:

def __init__(self, sequence):

self.__list = list(sequence)

test = Testlist([1, 2, 3])

print(test)

test[0]

del test[1]

iter(test)

reversed(test)

len(test)我们的目的是给Testlist类添加一些类似list中的方法(虽然我们实际上就是一个简单的调用)。我们并没有在类内一个个的设计方法,而是通过类修饰器。

再看Util类的delegate函数,这个函数需要一些参数,并返回一个类修饰器,类修饰器的理念和普通的修饰器的理念是一样的。

我们获取了attribute_name,即"__list",因为这个是私有属性,所以通过外部调用的时候需要通过_classname__attribute_name来调用。接着,对每一个method_name,我们为类cls添加一个属性(方法)。我们通过exec来动态的绑定,注意到,code的写法可能比较丑陋,但是没办法,不然缩进会导致程序报错。绑定方法,我们只是调用了原来的list方法,并添加了一个标记,程序的输出是:

welcome to __str__

[1, 2, 3]

welcome to __getitem__

welcome to __delitem__

welcome to __iter__

welcome to __reversed__

welcome to __len__8.2.6 抽象基类

PEP 3119 关于抽象基类的介绍

抽象基类(ABC)也是一个类,但不是用于创建对象,而是用于定义接口,也就是说,列出一些方法和特性——继承自ABC的类必须对其进行实现。这种机制是有用的,因为我们可以将抽象基类作为一种允诺——任何字ABC衍生而来的类必须实现抽线基类指定的方法与特性。

数值模块的抽象基类(表)

| ABC | 继承自 | API | 实例 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | object | complex, decimal.Decimal, float, fractions.Fraction, int | |

| Complex | Number | ==,!=, +, -, *, /, abs(), bool(), complex(), conjugate()以及real与imag特性 | complex,decimal.Decimal, float, fractions.Fraction, int |

| Real | Complex | <,<=,==,!=,=>,>,+,-,/,//,%,abs(),bool(),complex(),conjugate(),divmod(),float(),math.ceil(),math.floor(),round(),trunc();以及real与imag特性 | decimal.Decimal, float, fractions.Fraction, int |

| Rational | Real | <.<=,==,!=,>=,>,+,-,*,/,//,%,abs(),bool(),complex(),conjugate(),divmod(),float(),math.ceil(),math.floor(),round(),trunc();以及real,imag,numerator与denominartor特性 | fractions.Fraction,int |

| Integral | Rational | <,<=,==,!=,>=,>,+,-,*,/,//,%,<<,>>,~,&,^,|,abs(),bool(),complex(),conjugate(),divmod(),float(),math.ceil(),math.floor(),pow(),round(),TRunc();以及real,imag,numerator与denominator特性 | int |

组合模块的主抽象基类(表)

| ABC | 继承自 | API | 实例 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Callable | object | () | 所有函数、方法以及lambdas |

| Container | object | in | bytearray,bytes,dict,frozenset,list,set,str,tuple |

| Hashable | object | hash() | bytes, frozenset, str, tuple |

| Iterable | object | iter() | bytearray, bytes, collections.deque,dict,frozenset,list,set,str,tuple |

| Iterator | Iterable | iter(),next() | |

| Sized | object | len() | bytearray,bytes,collection.deque,dict,frozenset,list,set,str,tuple |

| Mapping | Container,Iterable,Sized | ==,!=,[],len(),iter(),in,get(),items(),keys(),values() | dict |

| Mutable-Mapping | Mapping | ==,!=,[],del,len(),iter(),in,clear(),get(),items(),keys(),pop(),popitem(),setdefault(),update(),values() | dict |

| Sequence | Container,Iterable,Sized | [], len(), iter(), reversed(), in, count(), index() | bytearray,bytes, list, str, tuple |

| Mutable-Sequence | Container,Iterable,Sized | [],+=,del,len(),iter(),reversed(),in,append(),count(),extend(),index(),insert(),pop(),remove(),reverse() | bytearray,list |

| Set | Container,Iterable,Sized | <,<=,==,!=, =>,>,&,|,^,len(),iter(),in,isdisjoint() | frozenset,set |

| MutableSet | Set | <,<=,==,!=,=>,>,&,|,^,&=,|=,^=,-=,len(),iter(),in,add(),clear(),discard(),isdisjoint(),pop(),remove() | set |

通俗地讲,我们为什么需要抽象基类。比方说,我们要对方法或者函数的输入进行一些检查,我们希望输入是一个序列,那么问题来了,什么是序列呢?有的人认为,序列就是拥有__len__属性的,有的认为是拥有__iter__属性的。但是通过抽象基类的Sequence,我们就能有一个统一的标准。抽象基类有很重要的一个东西是,抽象方法和抽象属性,如果一个类拥有抽象方法和抽象属性,那么它无法实例化,除非该方法被覆写。所以如果一个类继承自抽象基类,那么必须把抽象基类中的抽象方法和抽象属性进行覆写。这也就保证了,这类能够实现这些功能,比如一个Sequence应该拥有的那些功能,而不是其中的某几个。

下面是一个小小的例子:

import abc

class Appliance(metaclass=abc.ABCMeta):

@abc.abstractmethod

def __init__(self, model, price):

self.__model = model

self.price = price

def get_price(self):

return self.__price

def set_price(self, price):

self.__price = price

#就像我们所知道的,property实际上是一个类(实际上是描述符的用法)

#所以这里的price也是一个类,传入了get_price和set_price方法

#在子类中,我们同样必须实现price特性,但是并不一定需要实现setter方法

price = abc.abstractproperty(get_price, set_price)

@property

def model(self):

return self.__model

class Cooker(Appliance):

def __init__(self, model, price, fuel):

super().__init__(model, price)#注意,这里不用super()实际上也并没有问题

self.fuel = fuel

price = property(lambda self:super().price,

lambda self, price: super().set_price(price))class TextFilter(metaclass=abc.ABCMeta):

"""

这个类没有提供任何功能,其存在纯粹是为了定义

一个接口。

"""

@property #这部分本来是直接用@abc.abstractproperty

@abc.abstractmethod #但是显示弃用了...

def is_transformer(self):

raise NotImplementedError()

@abc.abstractmethod

def __call__(self):

raise NotImplementedError()

class CharCounter(TextFilter):

"""

这个类是上面的一个子类,我们可以利用这个类来计数。

"""

@property

def is_transformer(self):

return False

def __call__(self, text, chars):

count = 0

for c in text:

if c in chars:

count += 1

return count

vowel_counter = CharCounter()

print(vowel_counter("dog fish and cat fish", "aeiou")) # 5下面的例子是模拟撤销指令:

class Undo(metaclass=abc.ABCMeta)

@abc.abstractmethod

def __init__(self):

self.__undos = []

@property

@abc.abstractmethod

def can_undo(self):

return bool(self.__undos)

@abc.abstractmethod

def undo(self):

assert self.__undos, "nothing left to undo"

self.__undos.pop()(self)

def add_undo(self, undo):

self.__undos.append(undo)

class Stack(Undo):

def __init__(self):

super().__init__()

self.__stack = []

@property

def can_undo(self):

return super().can_undo

def undo(self):

super().undo()

def push(self, item):

self.__stack.append(item)

self.add_undo(lambda self:self.__stack.pop())

def pop(self):

item = self.__stack.pop()

self.add_undo(lambda self: self.__stack.append(item))

return item8.2.7 多继承

多继承是指某个类继承自俩个或多个类。多继承存在的问题是,可能导致同一个类被继承多次。这意味着,某个被调用的方法如果不在子类中,而是在俩个或多个基类中,那么被调用方法具体版本取决于方法的解析顺序,从而使得使用多继承得到的类存在模糊的可能。

通过使用单继承(一个基类),并设置一个元类,可以避免使用多继承。另外一种替代方案是使用多继承与一个具体的类,以及一个或多个抽象基类。另一种替代方案是使用单继承并对其他类的实例进行聚集。

下面的例子是对上面Stack类的一个扩展,支持了save和load操作。

import abc

class Undo(metaclass=abc.ABCMeta)

@abc.abstractmethod

def __init__(self):

self.__undos = []

@property

@abc.abstractmethod

def can_undo(self):

return bool(self.__undos)

@abc.abstractmethod

def undo(self):

assert self.__undos, "nothing left to undo"

self.__undos.pop()(self)

def add_undo(self, undo):

self.__undos.append(undo)

import pickle

class LoadSave:

def __init__(self, filename, *attribute_names):

self.filename = filename

self.__attribute_names = []

for name in attribute_names:

if name.startswith("__"):

name = "_" + self.__class__.__name__ + name

self.__attribute_names.append(name)

def save(self):

with open(self.filename, "wb") as fh:

data = []

for name in self.__attribute_names:

data.append(getattr(self, name))

pickle.dump(data, fh, pickle.HIGHEST_PROTOCOL)

def load(self):

with open(self.filename, "rb") as fh:

data = pickle.load(fh)

for name, value in zip(self.__attribute_names, data):

setattr(self, name, value)

class FileStack(Undo, LoadSave):

def __init__(self, filename):

Undo.__init__(self)

LoadSave.__init__(self, filename, "__stack")

self.__stack = []

def load(self):

super().load() #因为不至二义性,所以使用super()

self.clear() #原先的材料被覆盖,所以撤销列表不再有意义,清空

def clear(self):

self.__undos = []

@property

def can_undo(self):

return super().can_undo

def undo(self):

super().undo()

def push(self, item):

self.__stack.append(item)

self.add_undo(lambda self:self.__stack.pop())

def pop(self):

item = self.__stack.pop()

self.add_undo(lambda self: self.__stack.append(item))

return item

8.2.8 元类

元类之于类,就像类之于实例。也就是说,元类用于创建类,正如类用于创建实例一样。并且,正如我们可以使用isinstance()来判断某个实例是否属于某个类,我们也可以用issubclass()来判断某个类对象是否继承了其他类。

元类最简单的用途是使自定义类适合Python标准的ABC体系,比如,为使得SortedList是一个collections.Sequence,可以不继承ABC,而只是简单地将SortedList注册为一个collections.Sequence:

class SortedList:

...

collections.Sequence.register(SortedList)以这种方式注册一个类会提供一个许诺,即该类会提供其注册类的API,但并不能保证一定遵守这个许诺。元类的用途之一就是同时提供这种许诺与保证,另一个用途是以某种方式修改一个类(就像类修饰器所做的),当然,元类也可同时用于这俩个目的。

from collections.abc import Callable

class LoadableSaveable(type):

"""

>>> class Bad(metaclass=LoadableSaveable):

... def some_method(self): pass

Traceback (most recent call last):

...

AssertionError: class 'Bad' must provide a load() method

>>> class Good(metaclass=LoadableSaveable):

... def load(self): pass

... def save(self): pass

>>> g = Good()

"""

def __init__(cls, classname, bases, dictionary):

super().__init__(classname, bases, dictionary)

assert hasattr(cls, "load") and \

isinstance(getattr(cls, "load"),

Callable), \

"class '" + classname + "' must provide a load() method"

assert hasattr(cls, "load") and \

isinstance(getattr(cls, "save"),

Callable), \

"class '" + classname + "' must provide a save() method"

if __name__ == "__main__":

import doctest

doctest.testmod()

如果某个类需要充当元类,就必须继承自根本的元类基类type——或其某个子类。

from collections.abc import Callable

class AutoSlotProperties(type):

def __new__(mcl, classname, bases, dictionary):

"""__new__方法在类定义的时候就会运行?"""

slots = list(dictionary.get("__slots__", []))

for getter_name in [key for key in dictionary

if key.startswith("get_")]:

if isinstance(dictionary[getter_name], Callable):

name = getter_name[4:]

slots.append("__" + name)

getter = dictionary.pop(getter_name)

setter_name = "set_" + name

setter = dictionary.get(setter_name, None)

if (setter is None and

isinstance(setter, Callable)):

del dictionary[setter_name]

dictionary[name] = property(getter, setter)

dictionary["__slots__"] = tuple(slots)

return super().__new__(mcl, classname, bases, dictionary)

class Product(metaclass=AutoSlotProperties):

"""

>>> product = Product("101110110", "8mm Stapler")

>>> product.barcode, product.description

('101110110', '8mm Stapler')

>>> product.description = "8mm Stapler (long)"

>>> product.barcode, product.description

('101110110', '8mm Stapler (long)')

"""

def __init__(self, barcode, description):

self.__barcode = barcode

self.description = description

def get_barcode(self):

return self.__barcode

def get_description(self):

return self.__description

def set_description(self, description):

if description is not None or len(description) < 3:

self.__description = ""

else:

self.__description = description

if __name__ == "__main__":

import doctest

doctest.testmod()

上面的例子,作为对使用@property与@name.setter修饰器的一种替代,我们创建了相应的类,并使用简单的命名来标识特性。比如,某个类有形如get_name()与set_name()的方法,我们就可以期待该类有一个私有的__name特性,可以使用instance.name进行存取,以便获取并进行设置。

8.3 函数型程序设计

map, filter, reduce

映射 map:

map(function, iterable)

令function作用与iterable的每一个元素,返回一个迭代子

print(list(map(lambda x: x ** 2, [1, 2, 3, 4]))) # [1, 4, 9, 16]过滤 filter:

filter(function, iterable)

令function作用于iterable的每一个元素,并根据返回值判断是否保留该元素

print(list(filter(lambda x: x > 0, [1, -2, 3, -4]))) # [1, 3]降低 reduce:

reduce(function, iterable)

对iterable的头俩个值调用函数,之后对计算所得结果与第三个值调用函数,之后对计算所得结果与第四个值调用函数,依此类推,直至所有的值都进行了处理。

import numpy as np

from functools import reduce

print(reduce(lambda x, y: x + y, [1, -2, 3, -4])) # -2

A = np.arange(-5, 4).reshape(3, 3)

print(A)

"""

[[-5 -4 -3]

[-2 -1 0]

[1, 2, 3]]

"""

print(reduce(lambda x, y: x+y, A)) # [-6, -3, 0]Python内置的如all(), any(), max(), min(), sum()等函数都是符合降低函数定义的。

几个实例

import operator, os.path

reduce(operator.add, (os.path.getsize(x) for x in files))

reduce(operator.add, map(os.path.getsize, files))其中operator.add就相当于与lambda x,y: x+y,operator模块提供了一系列函数,免除了我们定义函数的工作。

operator.itemgetter(), operator.attrgetter()

operator.itemgetter()可以帮助我们随心的获得项

import operator

a = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6]

index = [0, 3, 5]

getter = operator.itemgetter(*index)

print(getter(a)) #(1, 4, 6)operator.attrgetter()可以帮助我们获得属性

class Test: pass

a = Test()

b = Test()

a.attr = 1

getter = operator.attrgetter("attr")

print(getter(a)) # 1

print(getter(b)) # AttributeError: 'Test' object has no attribute 'attr'8.3.1 偏函数

偏函数是指使用现存函数以及某些参数来创建函数,新建函数与原函数执行的功能相同,但是某些参数是固定的,因此调用者不需要传递这些参数。

下面是一个例子:

def partial(function, **kwargs):

def functioncopy(*args, **kwargs2):

kwargs.update(kwargs2)

return function(*args, **kwargs)

return functioncopy

enumerate1 = partial(enumerate, start=1)

for i, item in enumerate1([5, 3, 2, 8]):

print(i, item)

"""

1 5

2 3

3 2

4 8

"""我们也可以通过functools模块里的partial函数实现:

import functools

enumerate1 = functools.partial(enumerate, start=1)

for i, item in enumerate1([5, 3, 2, 8]):

print(i, item)我们也可以通过修饰器达成这一目的,就是有点蠢蠢的感觉:

def partial(**kwargs):

def decorate(function):

def wrapper(*args, **kwargs2):

kwargs.update(kwargs2)

return function(*args, **kwargs)

wrapper.__name__ = function.__name__

wrapper.__doc__ = function.__doc__

return wrapper

return decorate

@partial(start=1)

def enumerate1(*args, **kwargs):

return enumerate(*args, **kwargs)

for i, item in enumerate1([5, 3, 2, 8]):

print(i, item)

使用偏函数可以简化代码,尤其是在需要多次使用同样的参数调用同样函数的时候,比如,在每次调用open()来处理UTF-8编码的文本文件时,不需要指定模式参数与编码参数,而是可以创建俩个函数带有的参数:

import functools

reader = functools.partial(open, mode="rt", encoding="utf8")

writer = functools.partial(open, mode="wt", encoding="utf-8")8.3.2 协程

协程也是一种函数,特点是其处理过程可以在特定点挂起与恢复。因此,典型情况下,协程将执行到某个特定语句,之后执行过程被挂起等待某些数据。在这个挂起点上,程序的其他部分可以继续执行(通常是没有被挂起的其他协程)。一旦数据到来,协程就从挂起点恢复执行,执行一些处理(很可能时以到来的数据为基础),并可能将其处理结果发送给另一个协程。协程可以有多个入口点和退出点,因为挂起与恢复执行的位置都不止一处。

对数据执行独立操作

下面展示了一个对html文件处理的例子:

import re

import functools

import sys

def coroutine(function):

"""

对于未修饰的匹配器而言,存在一个小问题——初次创建时,应该着手执行,

以便推进到yield表达式语句等待第一个文本。

"""

@functools.wraps(function)

def wrapper(*args, **kwargs):

generator = function(*args, **kwargs)

next(generator) #通过执行next()使得协程函数进行到第一个yield表达式

return generator

return wrapper

@coroutine

def regex_matcher(receiver, regex, num):

while True:

print("观测者{num}号待命".format(num=num))

text = (yield)

print("观测者{num}号就绪".format(num=num))

for match in regex.finditer(text):

receiver.send(match)

@coroutine

def reporter():

ignore = frozenset({"style.css", "favicon.png", "index.html"})

while True:

print("审查者号待命")

mathch = (yield)

print("审查者号就绪")

if mathch is not None:

groups = mathch.groupdict()

if "url" in groups and groups["url"] not in ignore:

print("URL: ", groups["url"])

elif "h1" in groups:

print("H1: ", groups["h1"])

elif "h2" in groups:

print("H2:", groups["h2"])

URL_RE = re.compile(r"""href=(?P['"])(?P[^\1]+?)"""

r"""(?P=quote)""", re.IGNORECASE) #匹配url

flags = re.MULTILINE|re.IGNORECASE|re.DOTALL

H1_RE = re.compile(r"(?P.+?)

", flags) #匹配h1标题

H2_RE = re.compile(r"(?P.+?)

", flags) #匹配h2标题

receiver = reporter()

matchers = (regex_matcher(receiver, URL_RE, 1),

regex_matcher(receiver, H1_RE, 2),

regex_matcher(receiver, H2_RE, 3))

s = "href='www.MTandHJ{0}'\n" \

"h1 is a huge huge boy

\n" \

"h2 is a big big boy

\n" \

"h1 say he comes back now

\n" \

"h6 is tiny but cute, a little girl?

"

htmls = [s.format(i) for i in range(10)]

try:

for html in htmls:

for matcher in matchers:

matcher.send(html)

finally:

for matcher in matchers:

matcher.close()

receiver.close()

审查者号待命

观测者1号待命

观测者2号待命

观测者3号待命

观测者1号就绪

审查者号就绪

URL: www.MTandHJ0

审查者号待命

观测者1号待命

观测者2号就绪

审查者号就绪

H1: h1 is a huge huge boy

审查者号待命

审查者号就绪

H1: h1 say he comes back now

审查者号待命

观测者2号待命

观测者3号就绪

审查者号就绪

H2: h2 is a big big boy

审查者号待命

观测者3号待命

观测者1号就绪

审查者号就绪

。。。

***

构成流水线

有时候,创建数据处理流水线是有用的。简单地说,流水线就是一个或多个函数的组合,数据项被发送给第一个函数,该函数或者丢弃该数据项(过滤掉),或者将其传送给下一个函数(以某种方式)。第二个函数从第一个函数接受数据项,重复处理过程,丢弃或将数据项(可能转换为不同的形式)传递给下一个函数,以此类推。最后,数据项在经过多次处理以后以某种形式输出。

def coroutine(function):

def wrapper(*args, **kwargs):

result = function(*args, **kwargs)

next(result)

return result

wrapper.__name__ = function.__name__

wrapper.__doc__ = function.__doc__

return wrapper

@coroutine

def housekeeper():

while True:

member = (yield)

if member is not None:

print("Dear Mr.{0}, what can I do for you?".format(

member

))

@coroutine

def guarder2(receiver):

while True:

member = (yield)

if member.istitle():

receiver.send(member)

else:

print("sorry {0}, guarder2 stop you here...".format(

member

))

@coroutine

def guarder1(receiver, rule):

while True:

member = (yield)

try:

if member[1:1+len(rule)] == rule:

receiver.send(member)

else:

print("sorry {0}, guarder1 stop you here...".format(

member

))

except:

print("som-eth-ing wr-ong, bo-om~")

@coroutine

def get_member(receiver):

while True:

member = (yield)

if member is not None:

print("oh Mr.{0}, I'm just a tiny gate, don't kill me please...".format(

member

))

receiver.send(member)

members = ["Eric{0}".format(i) for i in range(5)] + \

["eirc{0}".format(i) for i in range(5)] + \

["Tom{0}".format(i) for i in range(5)]

passing = housekeeper()

passing = guarder2(passing)

passing = guarder1(passing, rule="ric")

passing = get_member(passing)

for member in members:

passing.send(member)

上面的例子模拟了一个客人进来,判断其是否符合要求,如果不符合,就让他滚的这么一个玩意儿,因为书本的例子不大好玩,也怪麻烦的,就想了这么一个例子,其输出如下:

oh Mr.Eric0, I'm just a tiny gate, don't kill me please...

Dear Mr.Eric0, what can I do for you?

oh Mr.Eric1, I'm just a tiny gate, don't kill me please...

Dear Mr.Eric1, what can I do for you?

oh Mr.Eric2, I'm just a tiny gate, don't kill me please...

Dear Mr.Eric2, what can I do for you?

oh Mr.Eric3, I'm just a tiny gate, don't kill me please...

Dear Mr.Eric3, what can I do for you?

oh Mr.Eric4, I'm just a tiny gate, don't kill me please...

Dear Mr.Eric4, what can I do for you?

oh Mr.eirc0, I'm just a tiny gate, don't kill me please...

sorry eirc0, guarder1 stop you here...

oh Mr.eirc1, I'm just a tiny gate, don't kill me please...

sorry eirc1, guarder1 stop you here...

oh Mr.eirc2, I'm just a tiny gate, don't kill me please...

sorry eirc2, guarder1 stop you here...

oh Mr.eirc3, I'm just a tiny gate, don't kill me please...

sorry eirc3, guarder1 stop you here...

oh Mr.eirc4, I'm just a tiny gate, don't kill me please...

sorry eirc4, guarder1 stop you here...

oh Mr.Tom0, I'm just a tiny gate, don't kill me please...

sorry Tom0, guarder1 stop you here...

oh Mr.Tom1, I'm just a tiny gate, don't kill me please...

sorry Tom1, guarder1 stop you here...

oh Mr.Tom2, I'm just a tiny gate, don't kill me please...

sorry Tom2, guarder1 stop you here...

oh Mr.Tom3, I'm just a tiny gate, don't kill me please...

sorry Tom3, guarder1 stop you here...

oh Mr.Tom4, I'm just a tiny gate, don't kill me please...

sorry Tom4, guarder1 stop you here...

***

8.4 实例:Valid

Valid例子,说明了如何利用描述符和类修饰器来系统的为属性定义范围。

import re

from numbers import Real

def valid_string(attr_name, empty_allowed=True, regex=None,

acceptable=None):

def decorator(cls):

name = "__" + attr_name

def getter(self):

return getattr(self, name)

def setter(self, value):

assert isinstance(value, str), (attr_name +

" must be a string")

if not empty_allowed and not value:

raise ValueError("{0} may not be empty".format(

attr_name

))

if ((acceptable is not None and value not in acceptable) or

(regex is not None and not regex.match(value))):

raise ValueError("{attr_name} cannot be set to "

"{value}".format(**locals()))

setattr(self, name, value)

setattr(cls, attr_name, GenericDescriptor(getter, setter))

return cls

return decorator

def valid_number(attr_name, minimum=None, maximum=None):

def decorator(cls):

name = "__" + attr_name

def getter(self):

return getattr(self, name)

def setter(self, value):

assert isinstance(value, Real), (attr_name +

" must be a number")

if (minimum is not None and value < minimum) or \

(maximum is not None and value > maximum):

s1 = "{0} <= ".format(minimum) if minimum is not None \

else ""

s2 = " <= {0}".format(maximum) if maximum is not None \

else ""

s = (s1 + "value" + s2 + " needed")

raise ValueError(s)

setattr(self, name, value)

setattr(cls, attr_name, GenericDescriptor(getter, setter))

return cls

return decorator

class GenericDescriptor: #类似Proerpty

def __init__(self, getter, setter):

self.getter = getter

self.setter = setter

def __get__(self, instance, owner=None):

if instance is None:

return self

return self.getter(instance)

def __set__(self, instance, value):

return self.setter(instance, value)

@valid_string("name", empty_allowed=False)

@valid_string("productid", empty_allowed=False,

regex=re.compile(r"[A-Z]{3}\d{4}"))

@valid_string("category", empty_allowed=False,

acceptable=frozenset(["Consumables", "Hardware",

"Software", "Media"]))

@valid_number("price", minimum=0, maximum=16)

@valid_number("quantity", minimum=1, maximum=1000)

class StockItem:

def __init__(self, name, productid, category, price, quantity):

self.name = name

self.productid = productid

self.category = category

self.price = price

self.quantity = quantity

if __name__ == "__main__":

test =[

(0, 1, 2, 3, 4),

("apple", "app123", "fruit", -1, 1001),

("apple", "APP1234", "fruit", -1, 1001),

("apple", "APP1234", "Hardware", -1, 1001),

("apple", "APP1234", "Hardware", 15, 1001),

("apple", "APP1234", "Hardware", 15, 888),

]

for item in test:

try:

StockItem(*item)

except (AssertionError, ValueError) as err:

print(item, err)