【Linux篇】第十四篇——多线程(一)(线程概念+线程控制)

Linux下的线程

线程的概念

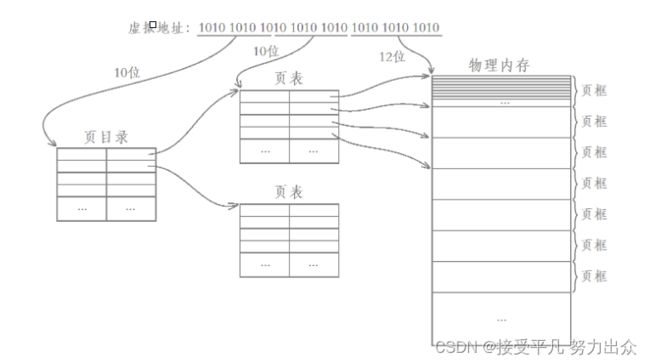

二级页表

线程的优点和缺点

线程异常

线程用途

Linux下的进程和线程

进程和线程

进程的多个线程共享

进程和线程的关系

Linux线程控制

POSIX线程库

线程创建

线程等待

线程终止

线程分离

线程ID及进程地址空间布局

Linux下的线程

线程的概念

- 在一个程序里的一个执行路线就叫做线程(thread)。更准确的定义是:线程是一个进程内部的控制序列。

- 一切进程至少都有一个执行线程。

- 线程在进程内部运行,本质是在进程地址空间内运行。

- 在Linux系统中,在CPU眼中,看到的PCB都要比传统的进程更轻量化。

- 透过进程虚拟地址空间,可以看到进程的大部分资源,将进程资源合理分配给每个执行流,就形成了线程执行流。

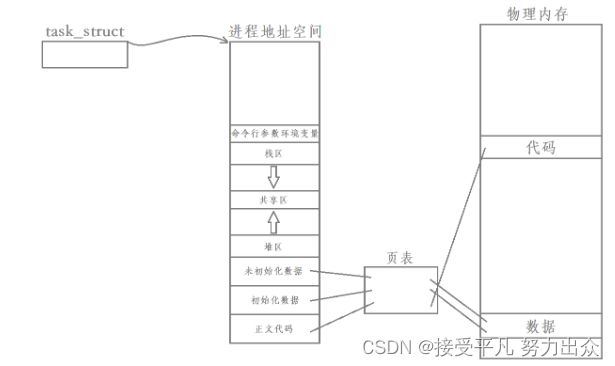

需要明确的是,一个进程的创建实际上伴随着其进程控制块(task_struct),进程地址空间(mm_struct)以及页表的创建,虚拟地址和物理地址就是通过页表建立映射的。

每个进程都有自己独立的进程地址空间和独立的页表,也就意味着所有进程在运行时本身就具有独立性。

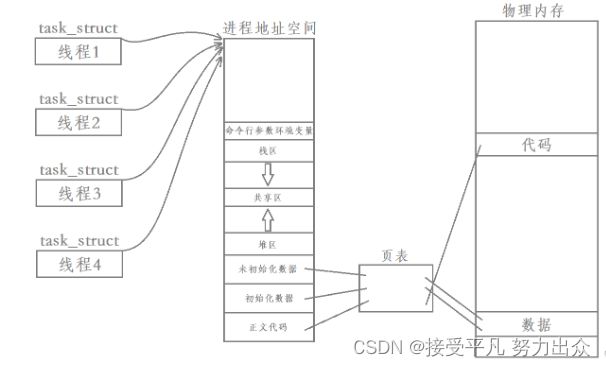

但如果我们在创建"进程"时,只创建task_struct,并要求创建出来的task_struct和父task_struct共享进程地址空间和页表,那么创建出来的结果就是下面这样"

此时我们创建的实际上就是四个线程:

- 其中每一个线程都是当前进程里面的一个执行流,也就是我们常说的“线程是进程内部的一个执行分支”。

- 同时我们也可以看出,线程在进程内部运行,本质就是线程在进程地址空间内运行,也就是说曾经这个进程申请的所有资源,几乎都是被所有线程共享的。

注意:单纯从技术角度,这个是一定可以实现的,因为它比创建一个原始进程所做的工作更加轻量化了。

该如何重新理解之前的进程?

下面用红色方框框起来的内容,我们将这个整体叫做进程。

因此,所谓的进程并不是通过task_struct来衡量的,除了task_struct之外,一个进程还要有进程地址空间、文件、信号等等,合起来称之为一个进程。

现在我们应该站在内核角度来理解进程:承担分配系统资源的基本实体,叫做进程。

换言之,当我们创建进程时是创建一个task_struct、创建地址空间、维护页表,然后在物理内存当中开辟空间、构建映射,打开进程默认打开的相关文件、注册信号对应的处理方案等等。

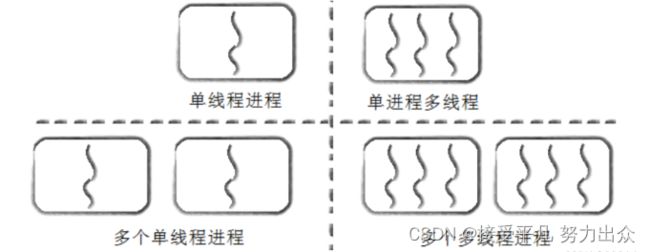

而我们之前接触到的进程都只有一个task_struct,也就是该进程内部只有一个执行流,即单执行流进程,反之,内部有多个执行流的进程叫做多执行流进程。

在Linux中,站在CPU的角度,能否识别当前调度的task_struct是进程还是线程?

答案是不能,也不需要了,因为CPU只关心一个一个的独立执行流。无论进程内部只有一个执行流还是有多个执行流,CPU都是以task_struct为单位进行调度的。

单执行流进程被调度:

多执行流进程被调度:

因此,CPU看到的虽说还是task_struct,但已经比传统的进程要更轻量化了。

Linux下并不存在真正的多线程!而是用进程模拟的!

操作系统中存在大量的进程,一个进程内又存在一个或多个线程,因此线程的数量一定比进程的数量多,当线程的数量足够多的时候,很明显线程的执行粒度要比进程更细。

如果一款操作系统要支持真的线程,那么就需要对这些线程进行管理。比如说创建线程、终止线程、调度线程、切换线程、给线程分配资源、释放资源以及回收资源等等,所有的这一套相比较进程都需要另起炉灶,搭建一套与进程平行的线程管理模块。

因此,如果要支持真的线程一定会提高设计操作系统的复杂程度。在Linux看来,描述线程的控制块和描述进程的控制块是类似的,因此Linux并没有重新为线程设计数据结构,而是直接复用了进程控制块,所以我们说Linux中的所有执行流都叫做轻量级进程。

但也有支持真的线程的操作系统,比如Windows操作系统,因此Windows操作系统系统的实现逻辑一定比Linux操作系统的实现逻辑要复杂得多。

既然在Linux没有真正意义的线程,那么也就绝对没有真正意义上的线程相关的系统调用!

这很好理解,既然在Linux中都没有真正意义上的线程了,那么自然也没有真正意义上的线程相关的系统调用了。但是Linux可以提供创建轻量级进程的接口,也就是创建进程,共享空间,其中最典型的代表就是vfork函数。

vfork函数的功能就是创建子进程,但是父子共享空间,v函数fork的函数原型如下:

pid_t vfork(void);

vfork函数的返回值与fork函数的返回值相同:

- 给父进程返回子进程的PID。

- 给子进程返回0。

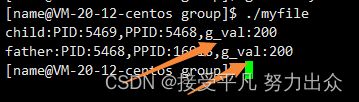

只不过vfork函数创建出来的子进程与其父进程共享地址空间,例如在下面的代码中,父进程使用vfork函数创建子进程,子进程将全局变量g_val由100改为了200,父进程休眠3秒后再读取到全局变量g_val的值。

#include

#include

#include

#include

int g_val = 100;

int main()

{

pid_t id = vfork();

if (id == 0){

//child

g_val = 200;

printf("child:PID:%d, PPID:%d, g_val:%d\n", getpid(), getppid(), g_val);

exit(0);

}

//father

sleep(3);

printf("father:PID:%d, PPID:%d, g_val:%d\n", getpid(), getppid(), g_val);

return 0;

}

可以看到,父进程读取到g_val的值是子进程修改后的值,也就证明了vfork创建的子进程与其父进程是共享地址空间的。

原生线程库pthread

在Linux中,站在内核角度没有真正意义上线程相关的接口,但是站在用户角度,当用户想创建一个线程时更期望使用thread_create这样类似的接口,而不是vfork函数,因此系统为用户层提供了原生线程库pthread。

原生线程库实际就是对轻量级进程的系统调用进行了封装,在用户层模拟实现了一套线程相关的接口。

因此对于我们来讲,在Linux下学习线程实际上就是学习在用户层模拟实现的这一套接口,而并非操作系统的接口。

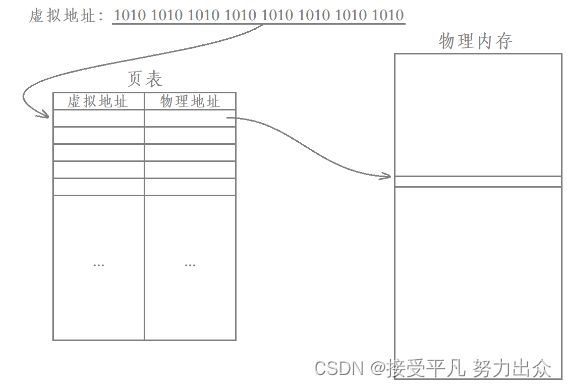

二级页表

以32位平台为例,在32位平台下一共有2^32个地址,也就意味着有2^32个地址需要被映射。

如果我们所谓的页表就只是单纯的一张表,那么这张表就需要建立2^32个虚拟地址和物理地址之间的映射关系,即这张表一共有2^32个映射表项。

每一个表项中除了要有虚拟地址和与其映射的物理地址以外,实际还需要有一些权限相关的信息,比如我们所说的用户级页表和内核级页表,实际就是通过权限进行区分的。

每个应表项中存储一个物理地址和一个虚拟地址就需要8个字节,考虑到还需要包含权限相关的各种信息,这里每一个表项就按10个字节计算。

这里一共有232个表项,也就意味着存储这张页表我们需要用232 * 10个字节,也就是40GB。而在32位平台下我们的内存可能一共就只有4GB,也就是说我们根本无法存储这样的一张页表。

因此所谓的页表并不是单纯的一张表。

还是以32位平台为例,其页表的映射过程如下:

- 选择虚拟地址的前10个比特位在页目录当中进行查找,找到对应的页表。

- 再选择虚拟地址的10个比特位在对应的页表当中进行查找,找到物理内存中对应页框的起始地址。

- 最后将虚拟地址中剩下的12个比特位作为偏移量从对应页框的起始地址处向后进行偏移,找到物理内存中某一个对应的字节数据。

相关说明:

- 物理内存实际是被划分成一个个4KB大小的页框的,而磁盘上的程序也是被划分成一个个4KB大小的页帧的,当内存和磁盘进行数据交换时也就是以4KB大小为单位进行加载和保存的。

- 4KB实际上就是2^12个字节,也就是说一个页框中有2^12个字节,而访问内存的基本大小是1字节,因此一个页框中就有2^12个地址,于是我们就可以将剩下的12个比特位作为偏移量,从页框的起始地址处开始向后进行偏移,从而找到物理内存中某一个对应字节数据。

这实际上就是我们所谓的二级页表,其中页目录项是一级页表,页表项是二级页表。

每一个表项还是按10字节计算,页目录和页表的表项都是2^10个,因此一个表的大小就是2^10 * 10个字节,也就是10KB。而页目录有2^10个表项也就意味着页表有2^10个,也就是说一级页表有1张,二级页表有2^10张,总共算下来大概就是10MB,内存消耗并不高,因此Linux中实际就是这样映射的。

上面所说的所有映射过程,都是由MMU(MemoryManagementUnit)这个硬件完成的,该硬件是集成在CPU内的。页表是一种软件映射,MMU是一种硬件映射,所以计算机进行虚拟地址到物理地址的转化采用的是软硬件结合的方式。

注意: 在Linux中,32位平台下用的是二级页表,而64位平台下用的是多级页表。

修改常量字符串为什么会触发段错误?

当我们要修改一个字符串常量时,虚拟地址必须经过页表映射找到对应的物理内存,而在查表过程中发现其权限是只读的,此时你要对其进行修改就会在MMU内部触发硬件错误,操作系统在识别到是哪一个进程导致的之后,就会给该进程发送信号对其进行终止。

线程的优点和缺点

优点:

- 创建一个新线程的代价要比创建一个新进程小得多

- 与进程之间的切换相比,线程之间的切换需要操作系统做的工作要少很多

- 线程占用的资源要比进程少很多。

- 能充分利用多处理器的可并行数量。

- 在等待慢速IO操作结束的同时,程序可执行其他的计算任务。

- 计算密集型应用,为了能在多处理器系统上运行,将计算分解到多个线程中实现。

- IO密集型应用,为了提高性能,将IO操作重叠,线程可以同时等待不同的IO操作。

计算机密集型:加密,大数据运算等->主要使用CPU资源

网络下载,云盘,ssh,在线直播,看电影->内存和外设得IO资源

缺点:

- 编程难度提高: 编写与调试一个多线程程序比单线程程序困难得多

- 健壮性降低: 编写多线程需要更全面更深入的考虑,在一个多线程程序里,因时间分配上的细微偏差或者因共享了不该共享的变量而造成不良影响的可能性是很大的,换句话说,线程之间是缺乏保护的。

- 性能损失: 一个很少被外部事件阻塞的计算密集型线程往往无法与其他线程共享同一个处理器。如果计算密集型线程的数量比可用的处理器多,那么可能会有较大的性能损失,这里的性能损失指的是增加了额外的同步和调度开销,而可用的资源不变。

- 缺乏访问控制: 进程是访问控制的基本粒度,在一个线程中调用某些OS函数会对整个进程造成影响。

线程异常

- 单个线程如果出现除零、野指针等问题导致线程崩溃,进程也会随着崩溃。

- 线程是进程的执行分支,线程出异常,就类似进程出异常,进而触发信号机制,终止进程,进程终止,该进程内的所有线程也就随即退出。

线程用途

- 合理的使用多线程,能提高CPU密集型程序的执行效率。

- 合理的使用多线程,能提高IO密集型程序的用户体验(如生活中我们一边写代码一边下载开发工具,就是多线程运行的一种表现)

Linux下的进程和线程

进程和线程

进程是承担分配系统资源的基本实体,线程是调度的基本单位。

线程共享进程数据,但也拥有自己的一部分数据:

- 调度优先级。

- 信号屏蔽字。

- errno。(C语言提供的全局变量,每个线程都有自己的)

- 栈。(每个线程都有临时的数据,需要压栈出栈)

- 一组寄存器。(存储每个线程的上下文信息)

- 线程ID。

进程的多个线程共享

因为是在同一个地址空间,因此所谓的代码段(Text Segment)、数据段(Data Segment)都是共享的:

- 如果定义一个函数,在各线程中都可以调用。

- 如果定义一个全局变量,在各线程中都可以访问到。

除此之外,各线程还共享以下进程资源和环境:

- 文件描述符表。(进程打开一个文件后,其他线程也能够看到)

- 每种信号的处理方式。(SIG_IGN、SIG_DFL或者自定义的信号处理函数)

- 当前工作目录。(cwd)

- 用户ID和组ID。

进程和线程的关系

进程和线程的关系如下图:

在此之前我们接触到的都是具有一个线程执行流的进程,即单线程进程。

Linux线程控制

POSIX线程库

pthread线程库是应用层得原生线程库:

- 应用层指的是这个线程库并不是系统接口直接提供的,而是由第三方帮我们提供的。

- 原生指的是大部分Linux系统都会默认带上该线程库。

- 与线程有关的函数构成了一个完整的系列,绝大多数函数的名字都是以“pthread_”打头的。

- 要使用这些函数库,要通过引入头文件

。 - 链接这些线程函数库时,要使用编译器命令的“-lpthread”选项。

错误检查:

- 传统的一些函数是,成功返回0,失败返回-1,并且对全局变量errno赋值以指示错误。

- pthreads函数出错时不会设置全局变量errno(而大部分POSIX函数会这样做),而是将错误代码通过返回值返回。

- pthreads同样也提供了线程内的errno变量,以支持其他使用errno的代码。对于pthreads函数的错误,建议通过返回值来判定,因为读取返回值要比读取线程内的errno变量的开销更小。

线程创建

创建线程的函数叫做pthread_create

pthread_create函数的函数原型如下:

int pthread_create(pthread_t *thread, const pthread_attr_t *attr, void *(*start_routine) (void *), void *arg);

参数说明:

- thread:获取创建成功的线程ID,该参数是一个输出型参数

- attr:用于设置创建线程的数学,传入NULL表示使用默认属性

- start_routine:该参数是一个函数地址,表示线程例程,即线程启动后要执行的函数

- arg:传给线程例程的参数

返回值说明:

- 线程创建成功返回0,失败返回错误码‘

让主线程创建一个新线程

当一个程序启动时,就有一个进程被操作系统创建,与此同时一个线程也立刻运行,这个线程就叫做主线程。

- 主线程是产生其他子进程的线程

- 通常主线程必须最后完成某些执行操作,比如各种关闭动作

下面我们让主线程调用pthread_create函数创建一个新线程,此后新线程就会跑去执行自己的新例程,而主线程则继续执行后续代码。

#include

#include

#include

void* Routine(void* arg)

{

while (1){

printf("我是新线程[%s],我创建的线程ID是:%lu\n",(const char*)args,pthread_self());

sleep(1);

}

}

int main()

{

pthread_t tid;

pthread_create(&tid, NULL, Routine, (void*)"new thread");

while (1){

printf("我是主线程,我创建的线程ID是:%lu,我的thread ID:%lu\n",tid,pthread_self());

sleep(2);

}

return 0;

}

运行代码后可以看到,新线程每隔一秒执行一次打印操作,而主线程每隔两秒执行一次打印操作

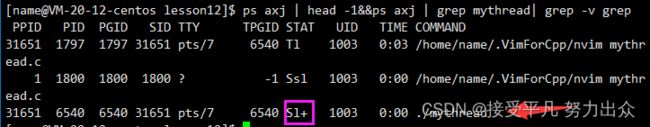

注意: 用pthread_self函数获得的线程ID与内核的LWP的值是不相等的,pthread_self函数获得的是用户级原生线程库的线程ID,而LWP是内核的轻量级进程ID,它们之间是一对一的关系。

当我们用ps axj命令查看当前进程的信息时,虽然此时该进程中有两个线程,但是我们看到的进程只有一个,因为这两个线程都是属于同一个进程的。

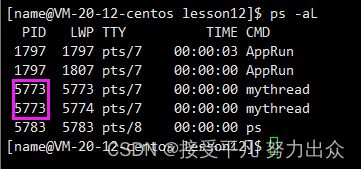

使用ps -aL命令,可以显示当前的轻量级进程。

- 默认情况下,不带-L,看到的就是一个个的进程

- 带-L就可以查看到每个进程内的多个轻量级进程

其中,LWP就是轻量级进程ID,可以看到显示的两个轻量级进程的PID是相同的,因为它们属于同一个进程。

注意:在Linux中,应用层的线程与内核的LWP是一一对应的,实际上操作系统调度的时候采用的是LWP,而并非PID,只不过我们之前接触到的都是单线程进程,其PID和LWP是相等的,所以对于单线程进程来说,调度时采用PID和LWP是一样的。

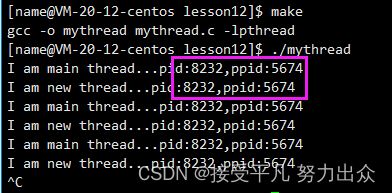

为了进一步证明这两个线程是属于同一个进程的,我们可以让主线程和新线程在执行打印操作时,将自己的PID和PPID也进行打印。

#include

#include

#include

#include

void* Routine(void* arg)

{

char* msg = (char*)arg;

while (1){

printf("I am %s...pid: %d, ppid: %d\n", msg, getpid(), getppid());

sleep(1);

}

}

int main()

{

pthread_t tid;

pthread_create(&tid, NULL, Routine, (void*)"thread 1");

while (1){

printf("I am main thread...pid: %d, ppid: %d\n", getpid(), getppid());

sleep(2);

}

return 0;

}

可以看到主线程和新线程的PID和PPID是一样的,也就是说主线程和新线程虽然是两个执行流,但它们仍然属于同一个进程。

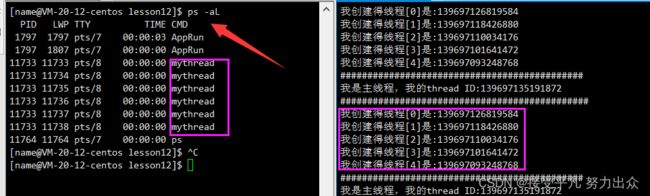

让主线程创建一批新线程

上面是让主线程创建一个新线程,下面我们让主线程一次性创建五个新进程,并让创建的每一个新线程都去执行Routine函数,也就是说Routine函数会被重新进入,即该函数是会被重入的。

#include

#include

#include

#include

void *thread_run(void* msg)

{

while(1)

{

sleep(3);

}

}

int main()

{

int i=0;

pthread_t tid[5];

for(i=0;i<5;i++)

{

pthread_create(tid+i,NULL,thread_run,(void*)"new thread");

}

while(1)

{

printf("我是主线程,我的thread ID:%lu\n",pthread_self());

printf("##############################################\n");

for(i=0;i<5;i++)

{

printf("我创建的线程[%d]是:%lu\n",i,tid[i]);

}

printf("##############################################\n");

sleep(1);

}

return 0;

} 运行代码,可以看到这五个新线程是创建成功的。因为主线程和五个新线程都属于同一个进程,所以它们的PID和PPID也都是一样的。此时我们再用ps -aL命令查看,就会看到六个轻量级进程。

注意:当其中一个线程发生异常崩溃时,其他线程也跟着全都崩溃,因此线程的健壮性不强.。

线程等待

首先需要明确的是,一个线程被创建出来,这个线程就如同进程一样,也是需要被等待的。如果主线程不对新线程进行等待,那么这个新线程的资源也是不会被回收的。所以线程需要被等待,如果不等待会产生类似于”僵尸进程"问题,也就是内存泄露。

等待线程的函数叫做pthread_join

pthread_join函数的函数原型如下:

int pthread_join(pthread_t thread, void **retval);

参数说明:

- thread:被等待线程的ID。

- retval:线程退出时的退出码信息。

返回值说明:

- 线程等待成功返回0,失败返回错误码。

调用该函数的线程将挂起等待,直到ID为thread的线程终止,thread线程以不同的方法终止,通过pthread_join得到的终止状态是不同的。

总结如下:

- 如果thread线程通过return返回,retval所指向的单元里存放的是thread线程函数的返回值。

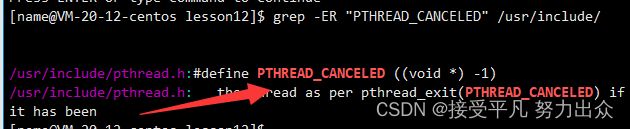

- 如果thread线程被别的线程调用pthread_cancel异常终止掉,retval所指向的单元里存放的是常数PTHREAD_CANCELED。

- 如果thread线程是自己调用pthread_exit终止的,retval所指向的单元存放的是传给pthread_exit的参数。

- 如果对thread线程的终止状态不感兴趣,可以传NULL给retval参数。

用grep命令进行查找,可以发现PTHREAD_CANCELED实际上就是头文件

[cl@VM-0-15-centos thread]$ grep -ER "PTHREAD_CANCELED" /usr/include/

例如,在下面的代码中我们先不关心线程的退出信息,直接将pthread_join函数的第二次参数设置为NULL,等待线程后打印该线程的编号以及线程ID。

#include

#include

#include

#include

#include

void* Routine(void* arg)

{

char* msg = (char*)arg;

int count = 0;

while (count < 5){

printf("I am %s...pid: %d, ppid: %d, tid: %lu\n", msg, getpid(), getppid(), pthread_self());

sleep(1);

count++;

}

return NULL;

}

int main()

{

pthread_t tid[5];

for (int i = 0; i < 5; i++){

char* buffer = (char*)malloc(64);

sprintf(buffer, "thread %d", i);

pthread_create(&tid[i], NULL, Routine, buffer);

printf("%s tid is %lu\n", buffer, tid[i]);

}

printf("I am main thread...pid: %d, ppid: %d, tid: %lu\n", getpid(), getppid(), pthread_self());

for (int i = 0; i < 5; i++){

pthread_join(tid[i], NULL);

printf("thread %d[%lu]...quit\n", i, tid[i]);

}

return 0;

}

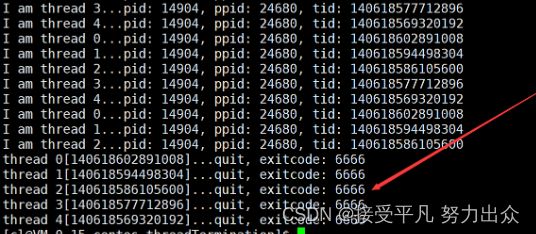

运行代码后,可以看到主线程创建的五个新线程在进行五次打印操作后就退出了,而主线程也是成功对这五个线程进行了等待

下面我们再来看看如何获取线程退出时的退出码,为了便于查看,我们这里将线程退出时的退出码设置为某个特殊的值,并在成功等待线程后将该线程的退出码进行输出。

#include

#include

#include

#include

#include

void* Routine(void* arg)

{

char* msg = (char*)arg;

int count = 0;

while (count < 5){

printf("I am %s...pid: %d, ppid: %d, tid: %lu\n", msg, getpid(), getppid(), pthread_self());

sleep(1);

count++;

}

return (void*)2022;

}

int main()

{

pthread_t tid[5];

for (int i = 0; i < 5; i++){

char* buffer = (char*)malloc(64);

sprintf(buffer, "thread %d", i);

pthread_create(&tid[i], NULL, Routine, buffer);

printf("%s tid is %lu\n", buffer, tid[i]);

}

printf("I am main thread...pid: %d, ppid: %d, tid: %lu\n", getpid(), getppid(), pthread_self());

for (int i = 0; i < 5; i++){

void* ret = NULL;

pthread_join(tid[i], &ret);

printf("thread %d[%lu]...quit, exitcode: %d\n", i, tid[i], (int)ret);

}

return 0;

}

运行代码,此时我们就拿到了每个线程退出时的退出码信息。

注意: pthread_join函数默认是以阻塞的方式进行线程等待的。

为什么线程退出时只能拿到线程的退出码?

如果我们等待的是一个进程,那么当这个进程退出时,我们可以通过wait函数或是waitpid函数的输出型参数status,获取到退出进程的退出码、退出信号以及core dump标志。

那为什么等待线程时我们只能拿到退出线程的退出码?难道线程不会出现异常吗?

线程在运行过程中当然也会出现异常,线程和进程一样,线程退出的情况也有三种:

- 代码运行完毕,结果正确。

- 代码运行完毕,结果不正确。

- 代码异常终止。

因此我们也需要考虑线程异常终止的情况,但是pthread_join函数无法获取到线程异常退出时的信息。因为线程是进程内的一个执行分支,如果进程中的某个线程崩溃了,那么整个进程也会因此而崩溃,此时我们根本没办法执行pthread_join函数,因为整个进程已经退出了。

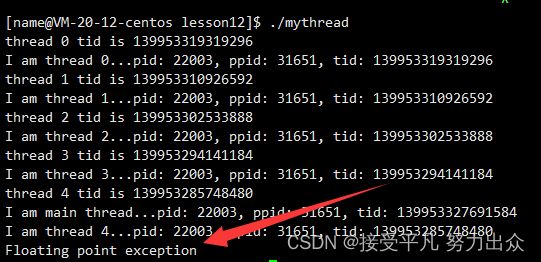

例如,我们在线程的执行例程当中制造一个除零错误,当某一个线程执行到此处时就会崩溃,进而导致整个进程崩溃。

#include

#include

#include

#include

#include

void* Routine(void* arg)

{

char* msg = (char*)arg;

int count = 0;

while (count < 5){

printf("I am %s...pid: %d, ppid: %d, tid: %lu\n", msg, getpid(), getppid(), pthread_self());

sleep(1);

count++;

int a = 1 / 0; //error

}

return (void*)2022;

}

int main()

{

pthread_t tid[5];

for (int i = 0; i < 5; i++){

char* buffer = (char*)malloc(64);

sprintf(buffer, "thread %d", i);

pthread_create(&tid[i], NULL, Routine, buffer);

printf("%s tid is %lu\n", buffer, tid[i]);

}

printf("I am main thread...pid: %d, ppid: %d, tid: %lu\n", getpid(), getppid(), pthread_self());

for (int i = 0; i < 5; i++){

void* ret = NULL;

pthread_join(tid[i], &ret);

printf("thread %d[%lu]...quit, exitcode: %d\n", i, tid[i], (int)ret);

}

return 0;

}

运行代码,可以看到一旦某个线程崩溃了,整个进程也就跟着挂掉了,此时主线程连等待新线程的机会都没有,这也说明了多线程的健壮性不太强,一个进程中只要有一个线程挂掉了,那么整个进程就挂掉了。并且此时我们也不知道是由于哪一个线程崩溃导致的,我们只知道是这个进程崩溃了。

所以pthread_join函数只能获取到线程正常退出时的退出码,用于判断线程的运行结果是否正确。

线程终止

如果需要只终止某个线程而不是终止整个进程,可以有三种方法:

- 从线程函数return。

- 线程可以自己调用pthread_exit函数终止自己。

- 一个线程可以调用pthread_cancel函数终止同一进程中的另一个线程。

return退出

在线程中使用return代表当前线程退出,但是在main函数中使用return代表整个进程退出,也就是说只要主线程退出了那么整个进程就退出了,此时该进程曾经申请的资源就会被释放,而其他线程会因为没有了资源,自然而然的也退出了。

例如,在下面代码中,主线程创建五个新线程后立刻进行return,那么整个进程也就退出了。

#include

#include

#include

#include

#include

void* Routine(void* arg)

{

char* msg = (char*)arg;

while (1){

printf("I am %s...pid: %d, ppid: %d, tid: %lu\n", msg, getpid(), getppid(), pthread_self());

sleep(1);

}

return (void*)0;

}

int main()

{

pthread_t tid[5];

for (int i = 0; i < 5; i++){

char* buffer = (char*)malloc(64);

sprintf(buffer, "thread %d", i);

pthread_create(&tid[i], NULL, Routine, buffer);

printf("%s tid is %lu\n", buffer, tid[i]);

}

printf("I am main thread...pid: %d, ppid: %d, tid: %lu\n", getpid(), getppid(), pthread_self());

return 0;

}

运行代码,并不能看到新线程执行的打印操作,因为主线程的退出导致整个进程退出了。

pthread_exit函数

pthread_exit函数的功能就是终止线程,pthread_exit函数的函数原型如下:

void pthread_exit(void *retval);

参数说明:

- retval:线程退出时的退出码信息。

说明一下:

- 该函数无返回值,跟进程一样,线程结束的时候无法返回它的调用者(自身)。

- pthread_exit或者return返回的指针所指向的内存单元必须是全局的或者是用malloc分配的,不能在线程函数的栈上分配,因为当其他线程得到这个返回指针时,线程函数已经退出了。

例如,在下面代码中,我们使用pthread_exit函数终止线程,并将线程的退出码设置为6666。

#include

#include

#include

#include

#include

void* Routine(void* arg)

{

char* msg = (char*)arg;

int count = 0;

while (count < 5){

printf("I am %s...pid: %d, ppid: %d, tid: %lu\n", msg, getpid(), getppid(), pthread_self());

sleep(1);

count++;

}

pthread_exit((void*)6666);

}

int main()

{

pthread_t tid[5];

for (int i = 0; i < 5; i++){

char* buffer = (char*)malloc(64);

sprintf(buffer, "thread %d", i);

pthread_create(&tid[i], NULL, Routine, buffer);

printf("%s tid is %lu\n", buffer, tid[i]);

}

printf("I am main thread...pid: %d, ppid: %d, tid: %lu\n", getpid(), getppid(), pthread_self());

for (int i = 0; i < 5; i++){

void* ret = NULL;

pthread_join(tid[i], &ret);

printf("thread %d[%lu]...quit, exitcode: %d\n", i, tid[i], (int)ret);

}

return 0;

}

运行代码可以看到,当线程退出时其退出码就是我们设置的6666。

注意: exit函数的作用是终止进程,任何一个线程调用exit函数也代表的是整个进程终止。

pthread_cancel函数

线程是可以被取消的,我们可以使用pthread_cancel函数取消某一个线程,pthread_cancel函数的函数原型如下:

int pthread_cancel(pthread_t thread);

参数说明:

- thread:被取消线程的ID。

返回值说明:

- 线程取消成功返回0,失败返回错误码。

线程是可以取消自己的,取消成功的线程的退出码一般是-1。例如在下面的代码中,我们让线程执行一次打印操作后将自己取消。

#include

#include

#include

#include

#include

void* Routine(void* arg)

{

char* msg = (char*)arg;

int count = 0;

while (count < 5){

printf("I am %s...pid: %d, ppid: %d, tid: %lu\n", msg, getpid(), getppid(), pthread_self());

sleep(1);

count++;

pthread_cancel(pthread_self());

}

pthread_exit((void*)6666);

}

int main()

{

pthread_t tid[5];

for (int i = 0; i < 5; i++){

char* buffer = (char*)malloc(64);

sprintf(buffer, "thread %d", i);

pthread_create(&tid[i], NULL, Routine, buffer);

printf("%s tid is %lu\n", buffer, tid[i]);

}

printf("I am main thread...pid: %d, ppid: %d, tid: %lu\n", getpid(), getppid(), pthread_self());

for (int i = 0; i < 5; i++){

void* ret = NULL;

pthread_join(tid[i], &ret);

printf("thread %d[%lu]...quit, exitcode: %d\n", i, tid[i], (int)ret);

}

return 0;

}

运行代码,可以看到每个线程执行一次打印操作后就退出了,其退出码不是我们设置的6666而是-1,因为我们是在线程执行pthread_exit函数前将线程取消的。

虽然线程可以自己取消自己,但一般不这样做,我们往往是用于一个线程取消另一个线程,比如主线程取消新线程。

例如,在下面代码中,我们在创建五个线程后立刻又将0、1、2、3号线程取消。

#include

#include

#include

#include

#include

void* Routine(void* arg)

{

char* msg = (char*)arg;

int count = 0;

while (count < 5){

printf("I am %s...pid: %d, ppid: %d, tid: %lu\n", msg, getpid(), getppid(), pthread_self());

sleep(1);

count++;

}

pthread_exit((void*)6666);

}

int main()

{

pthread_t tid[5];

for (int i = 0; i < 5; i++){

char* buffer = (char*)malloc(64);

sprintf(buffer, "thread %d", i);

pthread_create(&tid[i], NULL, Routine, buffer);

printf("%s tid is %lu\n", buffer, tid[i]);

}

pthread_cancel(tid[0]);

pthread_cancel(tid[1]);

pthread_cancel(tid[2]);

pthread_cancel(tid[3]);

printf("I am main thread...pid: %d, ppid: %d, tid: %lu\n", getpid(), getppid(), pthread_self());

for (int i = 0; i < 5; i++){

void* ret = NULL;

pthread_join(tid[i], &ret);

printf("thread %d[%lu]...quit, exitcode: %d\n", i, tid[i], (int)ret);

}

return 0;

}

此时可以发现,0、1、2、3号线程退出时的退出码不是我们设置的6666,而只有未被取消的4号线程的退出码是6666,因为只有4号进程未被取消。

此外,新线程也是可以取消主线程的,例如下面我们让每一个线程都尝试对主线程进行取消。

#include

#include

#include

#include

#include

pthread_t main_thread;

void* Routine(void* arg)

{

char* msg = (char*)arg;

int count = 0;

while (count < 5){

printf("I am %s...pid: %d, ppid: %d, tid: %lu\n", msg, getpid(), getppid(), pthread_self());

sleep(1);

count++;

pthread_cancel(main_thread);

}

pthread_exit((void*)6666);

}

int main()

{

main_thread = pthread_self();

pthread_t tid[5];

for (int i = 0; i < 5; i++){

char* buffer = (char*)malloc(64);

sprintf(buffer, "thread %d", i);

pthread_create(&tid[i], NULL, Routine, buffer);

printf("%s tid is %lu\n", buffer, tid[i]);

}

printf("I am main thread...pid: %d, ppid: %d, tid: %lu\n", getpid(), getppid(), pthread_self());

for (int i = 0; i < 5; i++){

void* ret = NULL;

pthread_join(tid[i], &ret);

printf("thread %d[%lu]...quit, exitcode: %d\n", i, tid[i], (int)ret);

}

return 0;

}

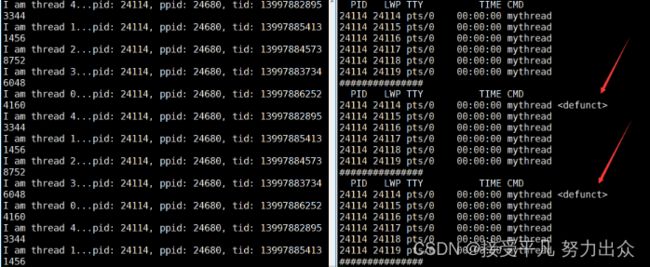

运行代码,同时用以下监控脚本进行实时监控。

while :; do ps -aL | head -1&&ps -aL | grep mythread | grep -v grep;echo "###############";sleep 1;done

可以看到一段时间后,六个线程中PID和LWP相同的线程,也就是主线程右侧显示

注意:

- 当采用这种取消方式时,主线程和各个新线程之间的地位是对等的,取消一个线程,其他线程也是能够跑完的,只不过主线程不再执行后续代码了。

- 我们一般都是用主线程去控制新线程,这才符合我们对线程控制的基本逻辑,虽然实验表明新线程可以取消主线程,但是并不推荐该做法。

线程分离

- 默认情况下,新创建的线程是joinable的,线程退出后,需要对其进行pthread_join操作,否则无法释放资源,从而造成内存泄漏。

- 但如果我们不关心线程的返回值,join也是一种负担,此时我们可以将该线程进行分离,后续当线程退出时就会自动释放线程资源。

- 一个线程如果被分离了,这个线程依旧要使用该进程的资源,依旧在该进程内运行,甚至这个线程崩溃了一定会影响其他线程,只不过这个线程退出时不再需要主线程去join了,当这个线程退出时系统会自动回收该线程所对应的资源。

- 可以是线程组内其他线程对目标线程进行分离,也可以是线程自己分离。

- joinable和分离是冲突的,一个线程不能既是joinable又是分离的。

分离线程的函数叫做pthread_detach

pthread_detach函数的函数原型如下:

int pthread_detach(pthread_t thread);

参数说明:

- thread:被分离线程的ID

返回值说明:

- 线程分离成功返回0,失败返回错误码。

例如,下面我们创建五个新线程后让这五个新线程将自己进行分离,那么此后主线程就不需要在对这五个新线程进行join了。

#include

#include

#include

#include

#include

void* Routine(void* arg)

{

pthread_detach(pthread_self());

char* msg = (char*)arg;

int count = 0;

while (count < 5){

printf("I am %s...pid: %d, ppid: %d, tid: %lu\n", msg, getpid(), getppid(), pthread_self());

sleep(1);

count++;

}

pthread_exit((void*)6666);

}

int main()

{

pthread_t tid[5];

for (int i = 0; i < 5; i++){

char* buffer = (char*)malloc(64);

sprintf(buffer, "thread %d", i);

pthread_create(&tid[i], NULL, Routine, buffer);

printf("%s tid is %lu\n", buffer, tid[i]);

}

while (1){

printf("I am main thread...pid: %d, ppid: %d, tid: %lu\n", getpid(), getppid(), pthread_self());

sleep(1);

}

return 0;

}

这五个新线程在退出时,系统会自动回收对应线程的资源,不需要主线程进行join

线程ID及进程地址空间布局

- pthread_create函数会产生一个线程ID,存放在第一个参数指向的地址中,该线程ID和内核中的LWP不是一回事。

- 内核中的LWP属于进程调度的范畴,因为线程是轻量级进程,是操作系统调度器的最小单位,所以需要一个数值来唯一表示该线程。

- pthread_create函数第一个参数指向一个虚拟内存单元,该内存单元的地址即为新创建线程的线程ID,这个ID属于NPTL线程库的范畴,线程库的后续操作就是根据该线程ID来操作线程的。

- 线程库NPTL提供的pthread_self函数,获取的线程ID和pthread_create函数第一个参数获取的线程ID是一样的。

pthread_t到底是什么类型呢?

首先,Linux不提供真正的线程,只提供LWP,也就意味着操作系统只需要对内核执行流LWP进行管理,而供用户使用的线程接口等其他数据,应该由线程库自己来管理,因此管理线程时的“先描述,再组织”就应该在线程库里进行。

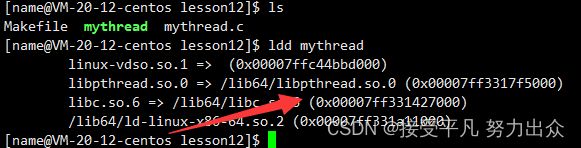

通过ldd命令可以看到,我们采用的线程库实际上是一个动态库。

进程运行时动态库被加载到内存,然后通过页表映射到进程地址空间中的共享区,此时该进程内的所有线程都是能看到这个动态库的

我们说每个线程都有自己私有的栈,其中主线程采用的栈是进程地址空间中原生的栈,而其余线程采用的栈就是在共享区中开辟的。除此之外,每个线程都有自己的struct pthread,当中包含了对应线程的各种属性;每个线程还有自己的线程局部存储,当中包含了对应线程被切换时的上下文数据。

每一个新线程在共享区都有这样一块区域对其进行描述,因此我们要找到一个用户级线程只需要找到该线程内存块的起始地址,然后就可以获取到该线程的各种信息。

上面我们所用的各种线程函数,本质都是在库内部对线程属性进行的各种操作,最后将要执行的代码交给对应的内核级LWP去执行就行了,也就是说线程数据的管理本质是在共享区的。

pthread_t到底是什么类型取决于实现,但是对于Linux目前实现的NPTL线程库来说,线程ID本质就是进程地址空间共享区上的一个虚拟地址,同一个进程中所有的虚拟地址都是不同的,因此可以用它来唯一区分每一个线程。

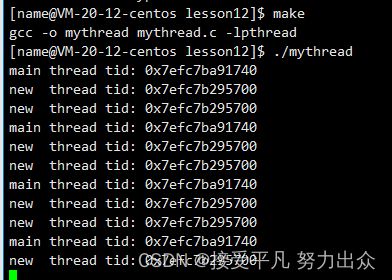

例如,我们也可以尝试按地址的形式对获取到的线程ID进行打印。

#include

#include

#include

void* Routine(void* arg)

{

while (1){

printf("new thread tid: %p\n", pthread_self());

sleep(1);

}

}

int main()

{

pthread_t tid;

pthread_create(&tid, NULL, Routine, NULL);

while (1){

printf("main thread tid: %p\n", pthread_self());

sleep(2);

}

return 0;

}

在此之前我们可以说这个打印结果很像一个地址,但是现在我们可以说,这本质就是一个地址。