Restriction (mathematics)

In mathematics, the restriction of a function {\displaystyle f}f is a new function, denoted {\displaystyle f\vert _{A}}{\displaystyle f\vert _{A}} or {\displaystyle f{\upharpoonright _{A}},}{\displaystyle f{\upharpoonright _{A}},} obtained by choosing a smaller domain {\displaystyle A}A for the original function {\displaystyle f.}f. The function {\displaystyle f}f is then said to extend {\displaystyle f\vert _{A}.}{\displaystyle f\vert _{A}.}

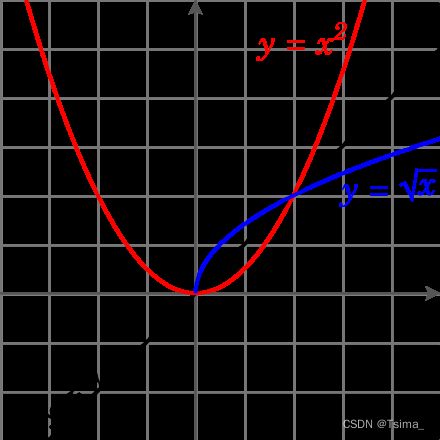

The function {\displaystyle x{2}}x{2} with domain {\displaystyle \mathbb {R} }\mathbb {R} does not have an inverse function. If we restrict {\displaystyle x{2}}x{2} to the non-negative real numbers, then it does have an inverse function, known as the square root of {\displaystyle x.}x.

Contents

- 1 Formal definition

-

- 1.1 Extensions

- 2 Examples

- 3 Properties of restrictions

- 4 Applications

-

- 4.1 Inverse functions

- 4.2 Selection operators

- 4.3 The pasting lemma

- 4.4 Sheaves

- 5 Left- and right-restriction

- 6 Anti-restriction

- 7 See also

1 Formal definition

Let {\displaystyle f:E\to F}{\displaystyle f:E\to F} be a function from a set {\displaystyle E}E to a set {\displaystyle F.}F. If a set {\displaystyle A}A is a subset of {\displaystyle E,}{\displaystyle E,} then the restriction of {\displaystyle f}f to {\displaystyle A}A is the function[1]

{\displaystyle {f|}{A}:A\to F}{\displaystyle {f|}{A}:A\to F}

given by {\displaystyle {f|}{A}(x)=f(x)}{\displaystyle {f|}{A}(x)=f(x)} for {\displaystyle x\in A.}{\displaystyle x\in A.} Informally, the restriction of {\displaystyle f}f to {\displaystyle A}A is the same function as {\displaystyle f,}f, but is only defined on {\displaystyle A}A.

If the function {\displaystyle f}f is thought of as a relation {\displaystyle (x,f(x))}(x,f(x)) on the Cartesian product {\displaystyle E\times F,}{\displaystyle E\times F,} then the restriction of {\displaystyle f}f to {\displaystyle A}A can be represented by its graph {\displaystyle G({f|}{A})={(x,f(x))\in G(f):x\in A}=G(f)\cap (A\times F),}{\displaystyle G({f|}{A})={(x,f(x))\in G(f):x\in A}=G(f)\cap (A\times F),} where the pairs {\displaystyle (x,f(x))}(x,f(x)) represent ordered pairs in the graph {\displaystyle G.}G.

1.1 Extensions

A function {\displaystyle F}F is said to be an extension of another function {\displaystyle f}f if whenever {\displaystyle x}x is in the domain of {\displaystyle f}f then {\displaystyle x}x is also in the domain of {\displaystyle F}F and {\displaystyle f(x)=F(x).}{\displaystyle f(x)=F(x).} That is, if {\displaystyle \operatorname {domain} f\subseteq \operatorname {domain} F}{\displaystyle \operatorname {domain} f\subseteq \operatorname {domain} F} and {\displaystyle F{\big \vert }{\operatorname {domain} f}=f.}{\displaystyle F{\big \vert }{\operatorname {domain} f}=f.}

A linear extension (respectively, continuous extension, etc.) of a function {\displaystyle f}f is an extension of {\displaystyle f}f that is also a linear map (respectively, a continuous map, etc.).

2 Examples

The restriction of the non-injective function{\displaystyle f:\mathbb {R} \to \mathbb {R} ,\ x\mapsto x^{2}}{\displaystyle f:\mathbb {R} \to \mathbb {R} ,\ x\mapsto x^{2}} to the domain {\displaystyle \mathbb {R} _{+}=[0,\infty )}{\displaystyle \mathbb {R} _{+}=[0,\infty )} is the injection{\displaystyle f:\mathbb {R} {+}\to \mathbb {R} ,\ x\mapsto x^{2}.}{\displaystyle f:\mathbb {R} {+}\to \mathbb {R} ,\ x\mapsto x^{2}.}

The factorial function is the restriction of the gamma function to the positive integers, with the argument shifted by one: {\displaystyle {\Gamma |}{\mathbb {Z} ^{+}}!(n)=(n-1)!}{\displaystyle {\Gamma |}{\mathbb {Z} ^{+}}!(n)=(n-1)!}

3 Properties of restrictions

Restricting a function {\displaystyle f:X\rightarrow Y}f:X\rightarrow Y to its entire domain {\displaystyle X}X gives back the original function, that is, {\displaystyle f|{X}=f.}{\displaystyle f|{X}=f.}

Restricting a function twice is the same as restricting it once, that is, if {\displaystyle A\subseteq B\subseteq \operatorname {dom} f,}{\displaystyle A\subseteq B\subseteq \operatorname {dom} f,} then {\displaystyle \left(f|{B}\right)|{A}=f|{A}.}{\displaystyle \left(f|{B}\right)|{A}=f|{A}.}

The restriction of the identity function on a set {\displaystyle X}X to a subset {\displaystyle A}A of {\displaystyle X}X is just the inclusion map from {\displaystyle A}A into {\displaystyle X.}X.[2]

The restriction of a continuous function is continuous.[3][4]