rust-异步学习

rust获取future中的结果

两种主要的方法使用 async: async fn 和 async 块

async 体以及其他 future 类型是惰性的:除非它们运行起来,否则它们什么都不做。

运行 Future 最常见的方法是 .await 它。

当 .await 在 Future 上调用时,它会尝试把 future 跑到完成状态。

如果 Future 被阻塞了,它会让出当前线程的控制权。

能取得进展时,执行器就会捡起这个 Future 并继续执行,让 .await 求解。

use futures::executor::block_on;

use futures::Future;

// `foo()` returns a type that implements `Futureasync 生命周期

async fn foo(x: &u8) -> u8 { *x }

// 等价于:

// impl Future + 'a 是 Rust 中的 trait bounds 格式

// 定义了一个 "future" 对象,用于异步计算并产生类型为 u8 的结果

// + 'a:这是一个 trait bounds 中的 "lifetime" 限定符,用于确定对象的生命周期。

// 它表示实现 Future trait 的对象被绑定在了一个叫做 'a 的生命周期上

// 具体使用,这个 'a 生命周期可以是当前函数的生命周期、闭包中的生命周期、也可以是调用者传入的生命周期等

// 总结:当前 "future" 对象实现了 Future trait 的对象,并且它的生命周期被限制在 'a 中

fn foo_expanded<'a>(x: &'a u8) -> impl Future + 'a {

// move 关键字告诉编译器引用的变量需要被捕获

// 如下闭包会 "移动"(Move)它所捕获的变量到闭包内部,在闭包的生命周期内都可以使用这些变量

// 即闭包会取得变量的所有权,即使在闭包外部变量的所有权已被转移也可以在闭包内部使用

// { *x } 将传入的 x 变量解引用并返回

// async move { *x } 的含义是异步闭包,在它的生命周期内获取变量 x 的所有权,、

// 将它解引用并作为 u8 类型的返回值

async move { *x }

}

如上意味着:这些 future 被 async fn 函数返回后必须要在它的非 'static 参数仍然有效时 .await

通常场景,future 在函数调用后马上 .await(例如 foo(&x).await)没问题

如果储存了这些 future 或者把它发送到其他的任务或者线程,那就有问题了

带有引用参数的 async fn 转化成 'static future

常用方法:把这些参数和对 async fn 的函数调用封装到async 块中

use futures::executor::block_on;

use futures::Future;

async fn borrow_x(x: &u8) -> u8 {

*x

}

fn good() -> impl Future {

async {

let x = 5;

// 参数 &x,表示传入一个 x 变量的不可变借用(borrow)

// 异步函数 borrow_x:返回值类型是 impl Future,即它会返回一个 Future 对象

// 在函数的返回值类型上调用 .await 表示暂停当前异步任务并等待结果的完成

// .await 关键字,可以使整个异步计算更高效,避免了阻塞等待异步任务完成的情况

// 通过移动参数到 async 块中,把它的生命周期扩展到了匹配调用 good 函数返回的 Future 的生命周期

borrow_x(&x).await

}

}

fn main() {

let ft = good();

let result = block_on(ft);

println!("{}", result);

}

use futures::executor::block_on;

use futures::Future;

fn bad() -> impl Future {

let x = 5;

borrow_x(&x) // ERROR: `x` does not live long enough

}

fn main() {

let ft = bad();

let result = block_on(ft);

println!("{}", result);

}

不使用move

在同一变量的作用域内,在多个不同的异步块(async block)中可以访问同一局部变量(local variable),而不会出现冲突。

use futures::Future;

use futures::executor::block_on;

async fn blocks() {

let my_string = "foo".to_string();

let future_one = async {

println!("{}", my_string);

};

let future_two = async {

println!("{}", my_string);

};

// Run both futures to completion, printing "foo" twice:

let ((), ()) = futures::join!(future_one, future_two);

}

fn main() {

let fut = blocks();

block_on(fut);

}

使用move

一个 async move 块会获取 所指向变量的所有权,允许它的生命周期超过当前作用域(outlive)

但是放弃了与其他代码共享这些变量的能力

use futures::Future;

use futures::executor::block_on;

fn move_block() -> impl Future {

let my_string = "foo".to_string();

async move {

println!("{}", my_string);

}

}

fn main() {

let fut = move_block();

block_on(fut);

}

在多线程执行器中 .await

线程间移动

在使用多线程的 Future 执行器时,一个 Future 可能在线程间移动

任何在 async 体中使用的变量必须能够穿过线程

任何 .await 都有可能导致线程切换

使用 Rc,&RefCell 或者其他没有实现 Send trait 的类型不安全

包括那些指向 没有 Sync trait 类型的引用。

(注意:使用这些类型是允许的,只要他们不是在调用 .await 的作用域内)

锁的使用

横跨 .await 持有一个非 future 感知的锁很不好

它能导致整个线程池 锁上

一个任务可能获得了锁,.await 然后让出到执行器,允许其他任务尝试获取所并导致死锁

解决方式:使用 futures::lock里的 Mutex 类型比起 std::sync 里面的更好

固定

固定的背景

// 该结构体的定义包含了一个名为 buf 的可变引用

struct ReadIntoBuf<'a> {

// buf 的生命周期不能超过它被声明的拥有者(结构体)的生命周期 'a

// 意味着 AsyncFuture 结构体必须声明一个具有足够长生命周期 &'a mut [u8]

buf: &'a mut [u8], // 指向 AsyncFuture 的成员x

}

// 该结构体包含一个名为 x 的 128 字节数组和一个 ReadIntoBuf 类型的字段

struct AsyncFuture {

x: [u8; 128],

// 在同一作用域内,x 的引用被传递给 read_into_buf_fut,使得异步方法中读取到 x 数组的数据

// 在 AsyncFuture 中,需要使用与 x 数组相同的生命周期注解 'what_lifetime?

// 确保 &mut 引用在结构体的生命周期内仍然有效

read_into_buf_fut: ReadIntoBuf<'what_lifetime?>,

}

假设 x 数组定义在当前作用域内

fn main() {

let mut x: [u8; 128] = [0; 128];

let read_into_buf_fut = ReadIntoBuf { buf: &mut x[..] };

// 在这种情况下,what_lifetime 就是当前作用域 main() 的生命周期,定义为 'static

let async_future = AsyncFuture { x, read_into_buf_fut };

}

因此,AsyncFuture 的定义应该是:

struct AsyncFuture<'a> {

x: [u8; 128],

// 使用单引号(')表示生命周期变量称为泛型参数,它是 ReadIntoBuf 中的泛型变量 'a 的值

// 泛型参数允许代码处理具有不同生命周期的值或类型,这种方式可以消除代码重复

read_into_buf_fut: ReadIntoBuf<'a>,

}

上述说了背景,但是最开始的例子的问题是什么?

ReadIntoBuf future 持有了一个指向其他字段 x 的引用。

如果 AsyncFuture 被移动,x 的位置(location)也会被移走

使得存储在 read_into_buf_fut.buf 的指针失效

固定的反面示例

固定future 到内存特定位置则阻止了上述问题,让创建指向 async 块的引用变得安全

// Rust 中的属性宏,用于自动生成结构体 Test 的 Debug trait 的实现代码以便后续调试使用

#[derive(Debug)]

struct Test {

a: String,

b: *const String,

}

// 定义Test结构体的方法集合

impl Test {

fn new(txt: &str) -> Self {

Test {

a: String::from(txt),

b: std::ptr::null(),

}

}

// 初始化 b 字段,赋予 a 字段的内存地址

fn init(&mut self) {

// *const String 指向 String 类型的不可变指针

let self_ref: *const String = &self.a;

// b 现在包含了 a 字段的内存地址值

// b 字段使用了一个原始指针

// b 指向 a 的引用,但由于 Rust 的借用规则,不能定义它的生命周期(lifetime)

// 所以把它存成指针。一个自引用结构体

self.b = self_ref;

}

fn a(&self) -> &str {

&self.a

}

// 返回 b 字段内存地址中所存储的值

fn b(&self) -> &String {

// 使用原始指针可能存在安全问题,因此通过 assert 语句增加了对 b 是否已经初始化的检查

// condition 的值为 false,则 assert! 宏会抛出一个 panic 异常并中断程序运行,同时输出一条错误信息

assert!(!self.b.is_null(), "Test::b called without Test::init being called first");

// unsafe:涉及到解引用一个原始指针,这个操作可能破坏类型系统的安全性质,所以用unsafe

// 首先对 self.b 进行解引用得到一个 &String 类型的指针

// 然后使用 unsafe 代码块获取这个指针所指向的 String 类型的值

unsafe { &*(self.b) }

}

}

fn main() {

let mut test1 = Test::new("test1");

test1.init();

let mut test2 = Test::new("test2");

test2.init();

println!("a: {}, b: {}", test1.a(), test1.b()); // a: test1, b: test1

println!("a: {}, b: {}", test2.a(), test2.b()); // a: test2, b: test2

}

如果上述列子改为如下:

// Rust 中的属性宏,用于自动生成结构体 Test 的 Debug trait 的实现代码以便后续调试使用

#[derive(Debug)]

struct Test {

a: String,

b: *const String,

}

// 定义Test结构体的方法集合

impl Test {

fn new(txt: &str) -> Self {

Test {

a: String::from(txt),

b: std::ptr::null(),

}

}

// 初始化 b 字段,赋予 a 字段的内存地址

fn init(&mut self) {

// *const String 是指一个指向 String 类型的不可变指针

let self_ref: *const String = &self.a;

// b 现在包含了 a 字段的内存地址值

// b 字段使用了一个原始指针

// b 指向 a 的引用,但由于 Rust 的借用规则,不能定义它的生命周期(lifetime)

// 所以把它存成指针。一个自引用结构体

self.b = self_ref;

}

fn a(&self) -> &str {

&self.a

}

// 返回 b 字段内存地址中所存储的值

fn b(&self) -> &String {

// 使用原始指针可能存在安全问题,因此通过 assert 语句增加了对 b 是否已经初始化的检查

assert!(!self.b.is_null(), "Test::b called without Test::init being called first");

// unsafe:涉及到解引用一个原始指针,这个操作可能破坏类型系统的安全性质,所以用unsafe

// 首先对 self.b 进行解引用得到一个 &String 类型的指针

// 然后使用 unsafe 代码块获取这个指针所指向的 String 类型的值

unsafe { &*(self.b) }

}

}

fn main() {

let mut test1 = Test::new("test1");

test1.init();

let mut test2 = Test::new("test2");

test2.init();

println!("a: {}, b: {}", test1.a(), test1.b()); // a: test1, b: test1

println!("a: {}, b: {}", test2.a(), test2.b()); // a: test2, b: test2

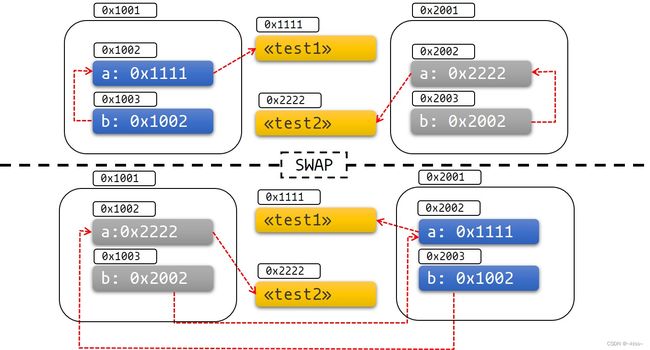

std::mem::swap(&mut test1, &mut test2);

println!("a: {}, b: {}", test1.a(), test1.b()); // a: test2, b: test1

println!("a: {}, b: {}", test2.a(), test2.b()); // a: test1, b: test2

}

结构体不再是自引用,它持有一个指向不同对象的字段的指针,导致未定义的行为

固定的实践

Pin 类型包装了指针类型, 保证没有实现 Unpin 指针指向的值不会被移动

例如, Pin<&mut T>, Pin<&T>, Pin

多数类型被移走也不会有问题。这些类型实现了 Unpin trait

指向 Unpin 类型的指针能够自由地放进 Pin,或取走。

例如,u8 是 Unpin 的,所以 Pin<&mut T> 的行为就像普通的 &mut T,就像普通的 &mut u8

固定后不能再移动的类型有一个标记 trait !Unpin

比如:async/await 创建的 Future

固定到栈上

Test类型实现了 !Unpin,那么固定这个类型的对象到栈上总是 unsafe 的行为

use std::pin::Pin;

use std::marker::PhantomPinned;

#[derive(Debug)]

// 使用 Pin 类型来创建自引用结构体

// 防止实例在被移动时其自引用指针变为无效

struct Test {

a: String,

b: *const String,

// 表示实例被初始化后,不能再被移动以保证自引用的合法性

_marker: PhantomPinned,

}

impl Test {

fn new(txt: &str) -> Self {

Test {

a: String::from(txt),

b: std::ptr::null(),

// 表示实例被初始化后,不能再被移动以保证自引用的合法性

_marker: PhantomPinned, // This makes our type `!Unpin`

}

}

fn init(self: Pin<&mut Self>) {

let self_ptr: *const String = &self.a;

// get_unchecked_mut :

// allows to obtain a mutable reference (&mut) to a descendant object

// without performing Rust's safety checks(不需要安全检查)

// Rust通过unsafe代码块来实现上述目的

// get_unchecked_mut 用在开发者自信地用其他方式保证安全性的环境中

// 在 Pin 的上下文之外对 Pin 实例进行借用时,必须使用 unsafe 代码

//

// self的类型:core::pin::Pin<&mut rust_demo1::Test>

// this的类型:&mut rust_demo1::Test

// 所以如下一行可以理解为:从Pin中取它包裹的类型

let this = unsafe { self.get_unchecked_mut() };

this.b = self_ptr;

}

// self的类型是Pin<&Self>,这个引用指向了一个暂时不可移动的 Test 实例

// 由于访问 get_ref() 值会把 Pin 引用变为常规引用,因此不需要 unsafe 代码块

// 在 Pin 上下文中,这种转换是有保证的

// 因为 Pin 分别对它的 T: Unpin 泛型 struct 和 Pin<&T> 应用了沙盒限制(sandboxing restrictions)

// 以防止 T 的 move 和 drop 操作

fn a(self: Pin<&Self>) -> &str {

// self.get_ref()的类型:&rust_demo1::Test

// &self.get_ref().a 的类型 &alloc::string::String,它被转换为 &str

&self.get_ref().a

}

fn b(self: Pin<&Self>) -> &String {

assert!(!self.b.is_null(), "Test::b called without Test::init being called first");

unsafe { &*(self.b) }

}

}

pub fn main() {

// test1 此时可移动

let mut test1 = Test::new("test1");

// 隐藏test1防止它被再次访问(重新赋值)

// 用 Pin::new_unchecked() 将 &mut Test 转换为 Pin<&mut Test> 引用

let mut test1 = unsafe { Pin::new_unchecked(&mut test1) };

Test::init(test1.as_mut());

let mut test2 = Test::new("test2");

let mut test2 = unsafe { Pin::new_unchecked(&mut test2) };

Test::init(test2.as_mut());

println!("a: {}, b: {}", Test::a(test1.as_ref()), Test::b(test1.as_ref()));

println!("a: {}, b: {}", Test::a(test2.as_ref()), Test::b(test2.as_ref()));

// 尝试移动,则报错

// std::mem::swap(test1.get_mut(), test2.get_mut());

}

固定到栈的注意事项

-

固定到栈总是依赖你在写 unsafe 代码时提供的保证

例如知道了 &'a mut T 的 被指向对象(pointee) 在生命周期 'a 期间固定,不知道被 &'a mut T 指向数据是否在 'a 结束后仍然不被移动。如果移动了,将会违反固定的协约。 -

忘记遮蔽(shadow)原本的变量

因为可以释放 Pin 然后移动数据到 &'a mut T,像下面这样(这违反了固定的协约):

fn main() {

let mut test1 = Test::new("test1");

// 没有隐藏test1

let mut test1_pin = unsafe { Pin::new_unchecked(&mut test1) };

Test::init(test1_pin.as_mut());

// 释放pin

drop(test1_pin);

// 交换前

// test1.b points to "test1": 0x7ff7bd6fcf50

// test1.a="test1", test1.b=0x7ff7bd6fcf50

println!(r#"test1.b points to "test1": {:?}"#, test1.b);

let mut test2 = Test::new("test2");

mem::swap(&mut test1, &mut test2);

// 交换后

// and now it points nowhere: 0x0

println!("and now it points nowhere: {:?}", test1.b);

// test1.a="test2", test1.b=0x0 违反了固定协约

// test2.a="test1", test2.b=0x7ff7bd6fcf50

}

固定到堆上

固定保证了实现了 !Unpin trait 的对象不会被移动

固定 !Unpin 类型到堆上,指向的数据不会在被固定之后被移动走。

和在栈上固定相反,整个对象的生命周期期间数据都会被固定在一处。

use std::pin::Pin;

use std::marker::PhantomPinned;

#[derive(Debug)]

struct Test {

a: String,

b: *const String,

_marker: PhantomPinned,

}

impl Test {

fn new(txt: &str) -> Pin<Box<Self>> {

let t = Test {

a: String::from(txt),

b: std::ptr::null(),

_marker: PhantomPinned,

};

let mut boxed = Box::pin(t);

let self_ptr: *const String = &boxed.a;

unsafe { boxed.as_mut().get_unchecked_mut().b = self_ptr };

boxed

}

fn a(self: Pin<&Self>) -> &str {

&self.get_ref().a

}

fn b(self: Pin<&Self>) -> &String {

unsafe { &*(self.b) }

}

}

pub fn main() {

let test1 = Test::new("test1");

let test2 = Test::new("test2");

println!("a: {}, b: {}",test1.as_ref().a(), test1.as_ref().b());

println!("a: {}, b: {}",test2.as_ref().a(), test2.as_ref().b());

}

一些函数需要的参数是 Unpin 的 future。

为了让这些函数使用不是 Unpin 的 Future/Stream,需要将future Pin住

Pin

- Box::pin 创建 Pin

- pin_utils::pin_mut! 创建 Pin<&mut T>

use pin_utils::pin_mut; // handy crate on crates.io

// 该函数需要Unpin的future

fn execute_unpin_future(x: impl Future<Output = ()> + Unpin) { /* ... */ }

// let fut = async { /* ... */ };

// Error: `fut` does not implement `Unpin` trait

// execute_unpin_future(fut);

// Pinning with `Box`:

let fut = async { /* ... */ };

let fut = Box::pin(fut);

execute_unpin_future(fut); // OK

// Pinning with `pin_mut!`:

let fut = async { /* ... */ };

pin_mut!(fut);

execute_unpin_future(fut); // OK

总结

(1)如果 T: Unpin(默认会实现),那么 Pin<'a, T> 完全等价于 &'a mut T。

换言之: Unpin 意味着这个类型被移走也没关系,就算已经被固定了,所以 Pin 对这样的类型毫无影响。

(2)如果 T: !Unpin, 获取已经被固定的 T 类型示例的 &mut T需要 unsafe。

(3)标准库中的大部分类型实现 Unpin,在 Rust 中遇到的多数“平常”的类型也是一样。但是, async/await 生成的 Future 是个例外。

(4)你可以在 nightly 通过特性标记来给类型添加 !Unpin 约束,或者在 stable 给你的类型加 std::marker::PhatomPinned 字段。

(5)你可以将数据固定到栈上或堆上

(6)固定 !Unpin 对象到栈上需要 unsafe

(7)固定 !Unpin 对象到堆上不需要 unsafe。Box::pin可以快速完成这种固定。

(8)对于 T: !Unpin 的被固定数据,你必须维护好数据内存不会无效的约定,或者叫 固定时起直到释放。这是 固定协约 中的重要部分。

附录

swap

// Rust 标准库中的函数,用于交换两个变量的值

std::mem::swap(&mut test1, &mut test2)

假设两个结构体变量 test1 和 test2:

struct Test {

val: i32,

}

let mut test1 = Test { val: 1 };

let mut test2 = Test { val: 2 };

swap之后,变量 test1 的值会被更新为 Test { val: 2 },变量 test2 的值会被更新为 Test { val: 1 }。

由于该函数会修改传入的变量的值,因此需要使用可变引用 &mut,并且只能在当前变量作用域内进行操作。

需要特别注意函数 std::mem::swap() 可能会导致“悬垂指针”等问题,因此在使用时需要仔细检查和评估潜在的风险。

get_unchecked_mut

允许通过可变引用(&mut)的方式,获取一个可变引用的后代对象(allows to obtain a mutable reference (&mut) to a descendant object),并且不能执行 Rust 的安全检查。

Rust 对于这类情况实现了飞腾支持,只要使用得当,就能安全地保证程序的执行安全性。

注意:

只有在开发者确信代码已经以其他方式保证安全性,才应该使用 get_unchecked_mut

比如:

(1)在 FFI(Foreign Function Interface)中调用 C 函数,必须使用 unsafe 代码来对其进行转换。如果要使用 rustc(Rust 编译器)检查 FFI 的安全性,则可能会出现假警告。

(2)在访问某个对象时,如果某种保证在代码中已经得到满足,那么就可以使用未经检查的代码。

这种函数典型的用法可以在使用 Pin 的例子中看到,它允许在 Pin 上下文中引用自身的某个字段。因为 Pin 类型本质上是一种安全约束,它的存在使得 Rust 可以保证在 Pin 的上下文之外不会发生安全问题。而由于代码库编写者不知道该类型的使用者在它的上下文中会做什么,在 Pin 的上下文之外对 Pin 实例进行借用时,必须使用 unsafe 代码。

new_unchecked

Pin::new_unchecked 方法允许将原始的不可变引用(&T)或可变引用(&mut T)转换为对应的 Pin 引用(即,Pin<&T> 或 Pin<&mut T>。转换后,Rust 不会再对被引用的对象执行安全性检查,因此开发者需要确保在遵循 Rust 的一般编码规范的情况下正确使用这个方法。

Pin 类型是一种用于强制不能在内存空间被移动的类型。在使用 Pin 时,必须遵循 Rust 的安全性规则,从而避免对 Pin 引用环境的破坏。

在 Pin 引用外部使用被引用的类型或类型上的方法时,Rust 编译器会自动执行安全性检查,但是,为 Pin 引用执行相同的检查会浪费宝贵的系统资源。

如何使用 Pin::new_unchecked 方法来创建 Pin 引用:

let my_ref = &mut my_struct;

let my_pin_ref = unsafe { Pin::new_unchecked(my_ref) };

注意:

使用 unsafe 代码块时,必须自行确保被引用的对象始终可用并符合 Pin 引用的要求,否则可能会引发安全性问题。

as_mut

用于将 Pin<&T> 引用转换为 Pin<&mut T> 引用,从而允许对元素进行安全的可变引用。该方法返回一个 Pin<&mut T> 引用。

注意:

由于 as_mut 方法本身不执行安全性检查,因此在使用时,需要确保 Pin 引用所包含的元素已经通过 Pin 约束得到保护。

假设有一个已经被pin的 Test 结构体,与其对应的 Pin 引用传递给了函数。

如果需要在函数中以可变方式修改 Test 中的某些元素,则可以使用 as_mut 方法将 Pin<&T> 引用转换为 Pin<&mut T> 引用:

fn do_something(test: Pin<&mut Test>) {

let a = test.as_mut().a_mut();

// Now we can mutate 'a' safely

a.push_str(", and then some");

}

在上面的代码中,as_mut 方法被用来将一个可变的引用返回给调用者,以便对结构体 Test 中的元素进行修改。

注意:

在调用 as_mut 之前,需要将 &mut Test 引用转换为 Pin<&mut Test> 引用,这在上面的函数中通过传递它进行实现。然后,在调用 as_mut 方法时,使用它来获取对最新可变的元素进行引用的引用,以便修改它。

说明:

因为 as_mut 方法是从不可变引用转换为可变引用,所以在使用引用链构建时,无法将其用于堆栈中即时生成的可变引用。

在这种情况下,在使用引用之前,必须先生成一个 Pin<&mut T> 引用,例如,通过使用 Pin::new_unchecked 方法。

个人理解:

貌似不是这么回事,待后续分析

47 // test1 is safe to move before we initialize it

48 let mut test1 = Test::new("test1");

49 // Notice how we shadow `test1` to prevent it from being accessed again

50 let mut test3 = unsafe{Pin::new_unchecked(&mut test1)};

51

52 print_type_of(&test3);

53 let tmp = unsafe{test3.as_mut()};

54 print_type_of(&tmp);

&String转&str

&String 类型可以转换为 &str 类型,因为 Rust 中的字符串(String)是 UTF-8 编码的。 &str 表示内存中的一块 UTF-8 编码的字符串。

可以通过添加引用符(&)并调用 as_str() 方法来将 &String 转换为 &str

let my_string = String::from("Hello, world!");

let my_str: &str = my_string.as_str();

也可以直接使用 & 符号引用String它并转换成 &str:

let my_string = String::from("Hello, world!");

let my_str: &str = &my_string;

这种方式天然地不存在内存分配问题,因此也是非常高效的。

请注意,在这里无需调用 as_str() 方法。

快速理解!Unpin和 Unpin

在 Rust 中,有一些类型是可以移动或重分配的,这些类型被标记为实现了 Unpin trait。

如果一个类型实现了 Unpin,它就可以在不限制语义和安全性的情况下,从一个位置移动到另一个位置。

如果一个类型没有实现 Unpin trait,则表明这个类型值在内存中不稳定,并且如果尝试在其上进行移动、重分配或者其他可能破坏内存稳定性的操作,就会导致编译时错误。

所以使用前先Pin住。

当使用 Pin 类型时,需要确保对这些约束和限制满足了正确地语义。在 Rust 中,通过使用 PhantomPinned 来标记类型为 !Unpin,表明这个类型的值可能不稳定,并且需要使用 Pin 类型在特定的上下文中使用。

handy crate

一个 Rust 社区中的第三方 crate,旨在为 Rust 开发人员提供实用的工具和辅助功能。

一些常见的功能及其描述:

-

try_trait

一个 trait 定义,可以用于实现方法 try,这个方法类似于 unwrap,但允许更好的错误处理和调试。 -

iter_ext

一个辅助模块,提供了一些常见且常用的迭代器操作,例如 dedup_by_key、intersperse、min_by_key 等。 -

clean

一个函数,可以安全地从字符串中删除 ASCII 控制字符,因为这些字符在终端输出和其他上下文中可能会引起错误。 -

extend_slice

一个扩展函数,可用于将一个 &[T] 切片扩展到具有给定长度的新切片。该函数可以在对于具有固定长度的数组的情况下特别有用。 -

resize_default

一个扩展函数,可用于将具有默认值的元素的向量扩展到指定的长度。 -

Loggable

一个 trait,可用于将任何类型转换为字符串,并将其用作日志。

除此之外,handy crate 还提供了一些其他的小工具和实用程序,如处理字符串和字节的函数、时间日期函数等。

handy crate 中的功能可以显著简化 Rust 开发人员的代码,并加速常见任务的开发。由于 handy 是一个第三方 crate,因此需要安装并将其导入到项目中才能使用它的功能。

// handy = "0.5.3"

use handy::iter_ext::IntersectExt;

fn main() {

let a = vec![1, 2, 3, 4];

let b = vec![1, 3, 5, 7, 9];

// 它扩展了标准库中的迭代器并更加方便易用

// 取交集

let intersect = a.intersect(b);

println!("{:?}", intersect);

}