Programming Languages PartC Week2学习笔记——OOP(面向对象) vs FD(函数式)

文章目录

-

-

- OOP Versus Functional Decomposition

- Adding Operations or Variants

- Binary Methods with Functional Decomposition

- Double Dispatch

- Optional: Multimethods

- Multiple Inheritance

- Mixins

- Interfaces

- Optional: Abstract Methods

-

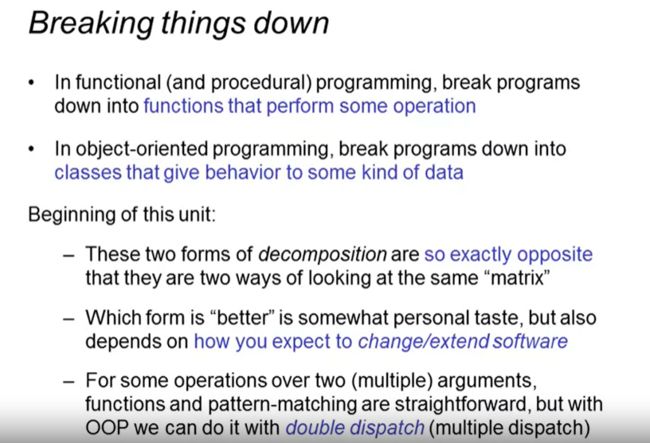

OOP Versus Functional Decomposition

面向对象与函数式(或过程式)编程的分解对比

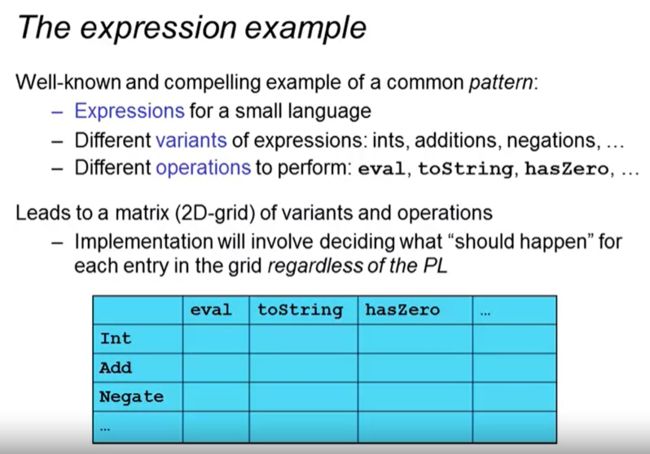

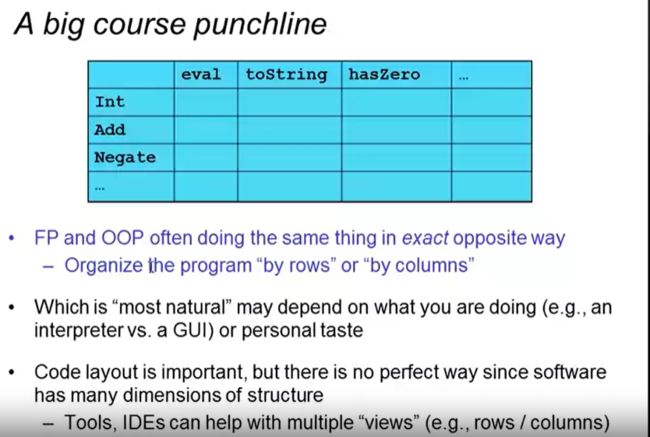

例子:不同的变量和操作构成了二维矩阵。

面向对象和函数式的思维方式不同。

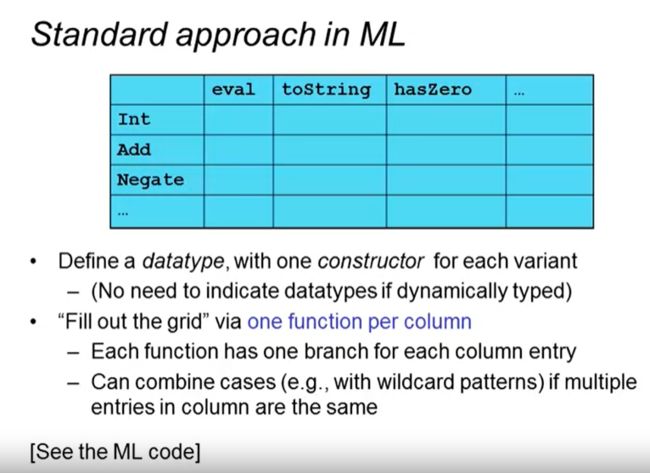

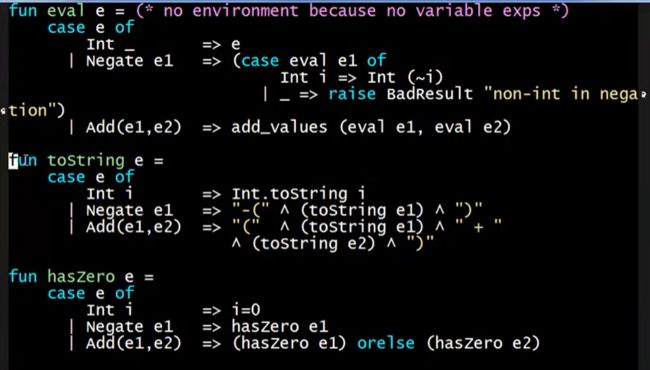

函数式编程的做法:通过函数填充每一列

面向对象编程:通过类填充每一行

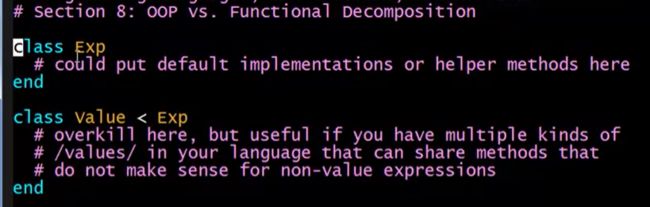

对Ruby而言:

对Java而言:

所以,事实上函数式编程FP和面向对象编程OOP都能做到同样的事情,但他们用了两种几乎相反的方式。具体使用什么方式,取决于做的事情和个人喜好。

Adding Operations or Variants

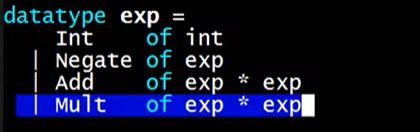

这一节涉及到对已有程序的维护迭代。例如分别以FP和OOP的视角来看增加操作或变量。

对于FP:

代码中增加方法非常容易,只需要增加一个函数即可,但增加变量对象就相对麻烦一些,不仅需要在原有定义的结构中添加新的变量,而且需要修改前面定义的所有方法,让其适应新的变量。这很容易理解。

对于OOP:

恰恰相反,添加一个变量只需要添加一个新的类(对象),但添加新的方法则需要修改已有的所有类(尽管可以使用继承或者一些设计模式来简化这一过程)。总之,也不难理解。

当然,我们总是希望能简化这个过程,让我们在使用某种方式编写程序(FP或OOP)时也能够使用另一种方式的优势(FP擅长新操作/方法,OOP擅长新变量/类)

最后是关于程序扩展性的一些编程哲学。

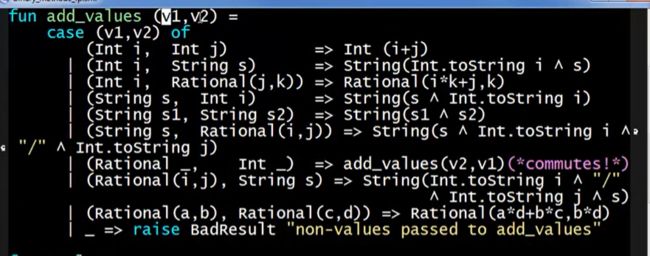

Binary Methods with Functional Decomposition

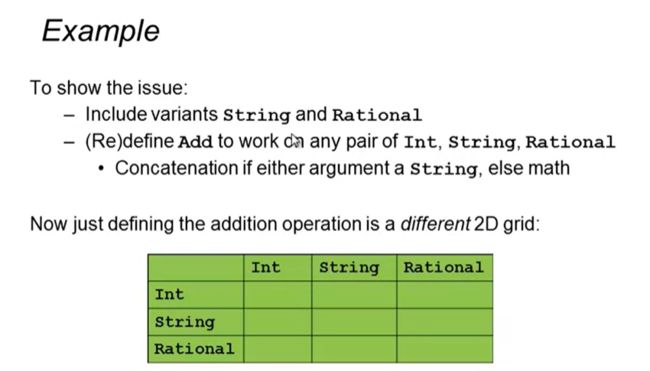

假如有一个操作需要定义在众多参数(而不是某个单个变量调用)的基础上,例如二元操作

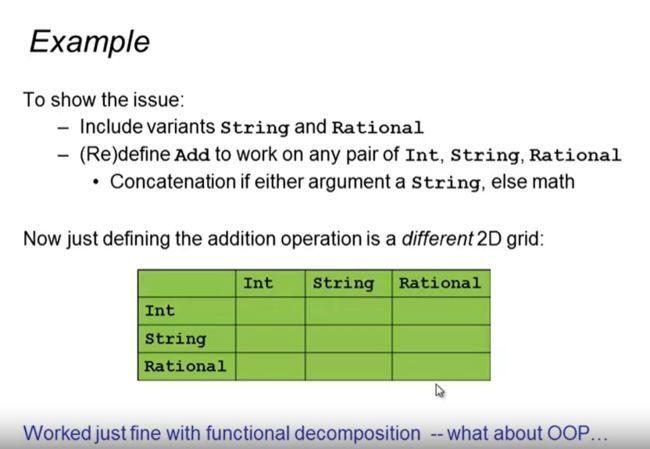

例子:这里的矩阵有所不同,不是变量Variants和操作Operation的关系,而是两个变量之间的关系。

ML的例子:因为要处理各个变体之间的关系,Add就不需要抛出异常

我们的eval过程需要定义所有情况(函数分解),就像绿色矩阵中那样

Double Dispatch

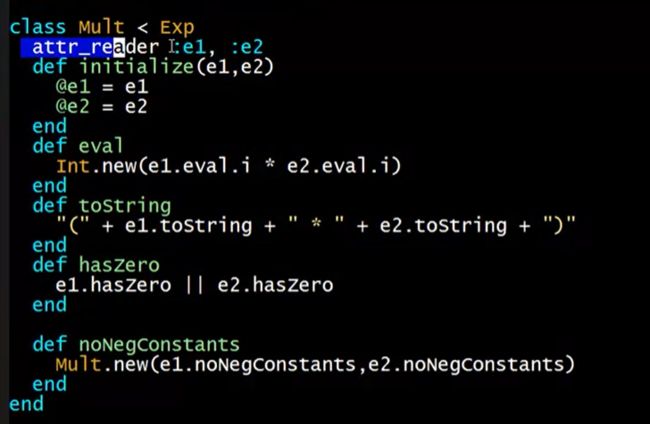

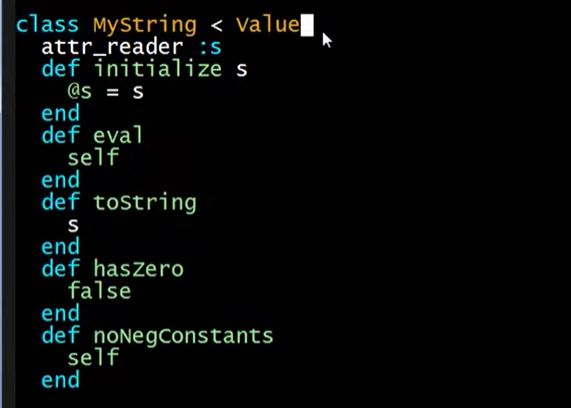

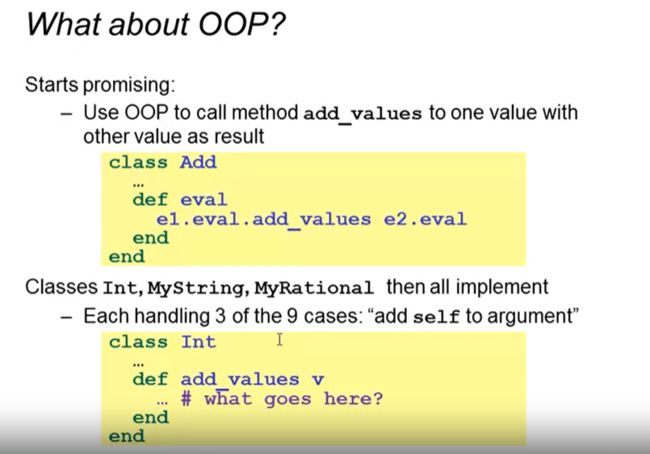

与上一节类似,本节要在Ruby中使用OOP的方式来实现类似的add_values操作,使用叫做双重分派的方式。

同样的,先定义数据结构,如下,Rational也类似。

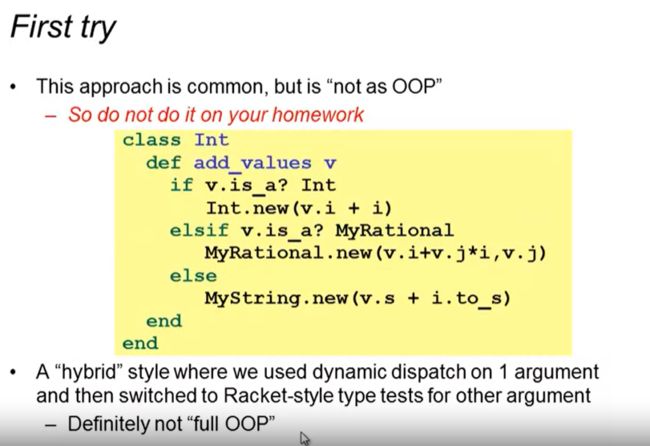

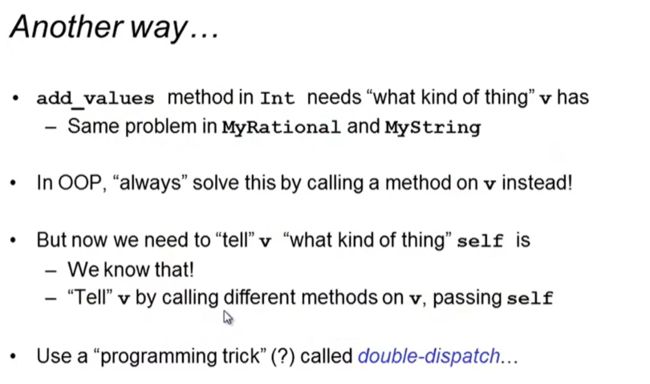

我们在某个类中总是需要识别其他对象的类,所以需要调用v对象的方法,但类似上述例子不是面向对象的方式(显式的判断v的类型)。我们确实需要“告诉”v,self是什么类型,这一点使用动态分派可以做到,这个技巧称为double-dispatch(即分派两次)。

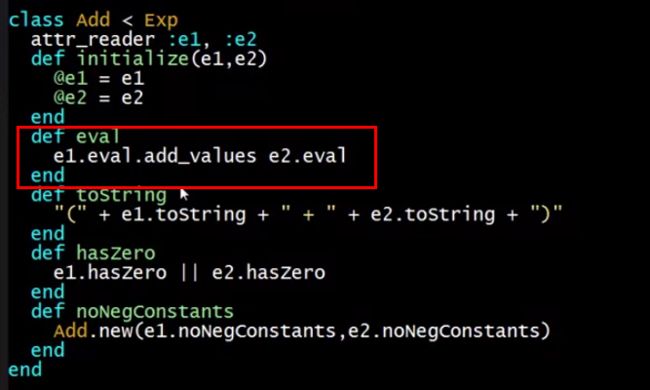

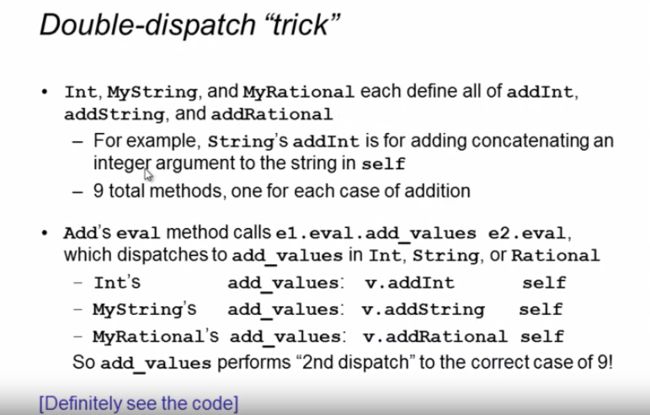

这里直接参考代码:

每个类仍然需要定义三个方法(addInt、addRational、addString),核心思想就是在每个类的add_values中调用v的对应方法,由于类本身是确定的,所以也能确定v使用的对应方法,例如v.addInt self,至于v是什么子类调用哪个子类方法,由动态分派决定,这是第一次分派。

然后v.addInt方法中的参数v就是之前的self,是确定的(从程序员角度),但程序调用v.i方法仍然需要动态分派确定哪个子类的方法,这是第二次分派。

# Section 8: Binary Methods with OOP: Double Dispatch

# Note: If Exp and Value are empty classes, we do not need them in a

# dynamically typed language, but they help show the structure and they

# can be useful places for code that applies to multiple subclasses.

class Exp

# could put default implementations or helper methods here

end

class Value < Exp

# this is overkill here, but is useful if you have multiple kinds of

# /values/ in your language that can share methods that do not make sense

# for non-value expressions

end

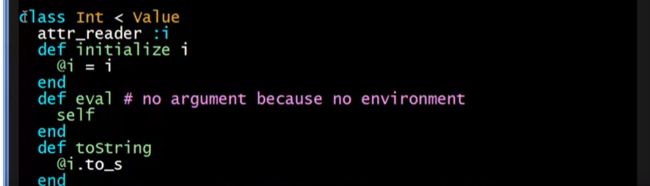

class Int < Value

attr_reader :i

def initialize i

@i = i

end

def eval # no argument because no environment

self

end

def toString

@i.to_s

end

def hasZero

i==0

end

def noNegConstants

if i < 0

Negate.new(Int.new(-i))

else

self

end

end

# double-dispatch for adding values

def add_values v # first dispatch

v.addInt self

end

def addInt v # second dispatch: other is Int

Int.new(v.i + i)

end

def addString v # second dispatch: other is MyString (notice order flipped)

MyString.new(v.s + i.to_s)

end

def addRational v # second dispatch: other is MyRational

MyRational.new(v.i+v.j*i,v.j)

end

end

# new value classes -- avoiding name-conflict with built-in String, Rational

class MyString < Value

attr_reader :s

def initialize s

@s = s

end

def eval

self

end

def toString

s

end

def hasZero

false

end

def noNegConstants

self

end

# double-dispatch for adding values

def add_values v # first dispatch

v.addString self

end

def addInt v # second dispatch: other is Int (notice order is flipped)

MyString.new(v.i.to_s + s)

end

def addString v # second dispatch: other is MyString (notice order flipped)

MyString.new(v.s + s)

end

def addRational v # second dispatch: other is MyRational (notice order flipped)

MyString.new(v.i.to_s + "/" + v.j.to_s + s)

end

end

class MyRational < Value

attr_reader :i, :j

def initialize(i,j)

@i = i

@j = j

end

def eval

self

end

def toString

i.to_s + "/" + j.to_s

end

def hasZero

i==0

end

def noNegConstants

if i < 0 && j < 0

MyRational.new(-i,-j)

elsif j < 0

Negate.new(MyRational.new(i,-j))

elsif i < 0

Negate.new(MyRational.new(-i,j))

else

self

end

end

# double-dispatch for adding values

def add_values v # first dispatch

v.addRational self

end

def addInt v # second dispatch

v.addRational self # reuse computation of commutative operation

end

def addString v # second dispatch: other is MyString (notice order flipped)

MyString.new(v.s + i.to_s + "/" + j.to_s)

end

def addRational v # second dispatch: other is MyRational (notice order flipped)

a,b,c,d = i,j,v.i,v.j

MyRational.new(a*d+b*c,b*d)

end

end

class Negate < Exp

attr_reader :e

def initialize e

@e = e

end

def eval

Int.new(-e.eval.i) # error if e.eval has no i method

end

def toString

"-(" + e.toString + ")"

end

def hasZero

e.hasZero

end

def noNegConstants

Negate.new(e.noNegConstants)

end

end

class Add < Exp

attr_reader :e1, :e2

def initialize(e1,e2)

@e1 = e1

@e2 = e2

end

def eval

e1.eval.add_values e2.eval

end

def toString

"(" + e1.toString + " + " + e2.toString + ")"

end

def hasZero

e1.hasZero || e2.hasZero

end

def noNegConstants

Add.new(e1.noNegConstants,e2.noNegConstants)

end

end

class Mult < Exp

attr_reader :e1, :e2

def initialize(e1,e2)

@e1 = e1

@e2 = e2

end

def eval

Int.new(e1.eval.i * e2.eval.i) # error if e1.eval or e2.eval has no i method

end

def toString

"(" + e1.toString + " * " + e2.toString + ")"

end

def hasZero

e1.hasZero || e2.hasZero

end

def noNegConstants

Mult.new(e1.noNegConstants,e2.noNegConstants)

end

end

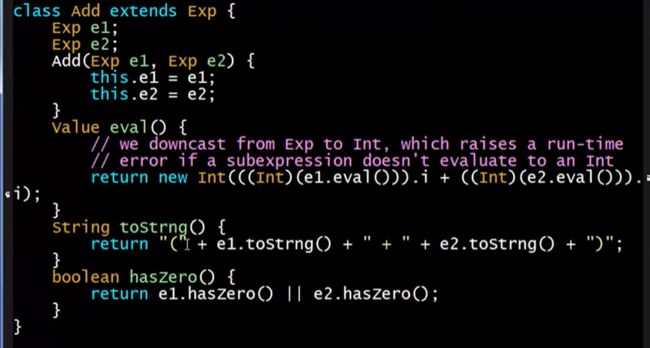

对于操作Add而言,其eval方法需要首先调用自身e1和e2的eval(可能是Int等数据结构的eval也可能是操作Add的eval递归调用,动态分派,让e1、e2自己决定调用子类方法)。

对于静态类型语言例如Java,也同样适用双重分派,所以double-dispatch是一种实现OOP二元操作的重要方法。

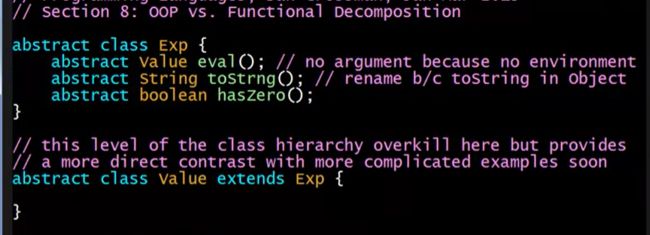

下面看看Java代码:

// Section 8: Binary Methods with OOP: Double Dispatch

abstract class Exp {

abstract Value eval(); // no argument because no environment

abstract String toStrng(); // renaming b/c toString in Object is public

abstract boolean hasZero();

abstract Exp noNegConstants();

}

abstract class Value extends Exp {

abstract Value add_values(Value other); // first dispatch

abstract Value addInt(Int other); // second dispatch

abstract Value addString(MyString other); // second dispatch

abstract Value addRational(Rational other); // second dispatch

}

class Int extends Value {

public int i;

Int(int i) {

this.i = i;

}

Value eval() {

return this;

}

String toStrng() {

return "" + i;

}

boolean hasZero() {

return i==0;

}

Exp noNegConstants() {

if(i < 0)

return new Negate(new Int(-i));

else

return this;

}

Value add_values(Value other) {

return other.addInt(this);

}

Value addInt(Int other) {

return new Int(other.i + i);

}

Value addString(MyString other) {

return new MyString(other.s + i);

}

Value addRational(Rational other) {

return new Rational(other.i+other.j*i,other.j);

}

}

class MyString extends Value {

public String s;

MyString(String s) {

this.s = s;

}

Value eval() {

return this;

}

String toStrng() {

return s;

}

boolean hasZero() {

return false;

}

Exp noNegConstants() {

return this;

}

Value add_values(Value other) {

return other.addString(this);

}

Value addInt(Int other) {

return new MyString("" + other.i + s);

}

Value addString(MyString other) {

return new MyString(other.s + s);

}

Value addRational(Rational other) {

return new MyString("" + other.i + "/" + other.j + s);

}

}

class Rational extends Value {

int i;

int j;

Rational(int i, int j) {

this.i = i;

this.j = j;

}

Value eval() {

return this;

}

String toStrng() {

return "" + i + "/" + j;

}

boolean hasZero() {

return i==0;

}

Exp noNegConstants() {

if(i < 0 && j < 0)

return new Rational(-i,-j);

else if(j < 0)

return new Negate(new Rational(i,-j));

else if(i < 0)

return new Negate(new Rational(-i,j));

else

return this;

}

Value add_values(Value other) {

return other.addRational(this);

}

Value addInt(Int other) {

return other.addRational(this); // reuse computation of commutative operation

}

Value addString(MyString other) {

return new MyString(other.s + i + "/" + j);

}

Value addRational(Rational other) {

int a = i;

int b = j;

int c = other.i;

int d = other.j;

return new Rational(a*d+b*c,b*d);

}

}

class Negate extends Exp {

public Exp e;

Negate(Exp e) {

this.e = e;

}

Value eval() {

// we downcast from Exp to Int, which will raise a run-time error

// if the subexpression does not evaluate to an Int

return new Int(- ((Int)(e.eval())).i);

}

String toStrng() {

return "-(" + e.toStrng() + ")";

}

boolean hasZero() {

return e.hasZero();

}

Exp noNegConstants() {

return new Negate(e.noNegConstants());

}

}

class Add extends Exp {

Exp e1;

Exp e2;

Add(Exp e1, Exp e2) {

this.e1 = e1;

this.e2 = e2;

}

Value eval() {

return e1.eval().add_values(e2.eval());

}

String toStrng() {

return "(" + e1.toStrng() + " + " + e2.toStrng() + ")";

}

boolean hasZero() {

return e1.hasZero() || e2.hasZero();

}

Exp noNegConstants() {

return new Add(e1.noNegConstants(), e2.noNegConstants());

}

}

class Mult extends Exp {

Exp e1;

Exp e2;

Mult(Exp e1, Exp e2) {

this.e1 = e1;

this.e2 = e2;

}

Value eval() {

// we downcast from Exp to Int, which will raise a run-time error

// if either subexpression does not evaluate to an Int

return new Int(((Int)(e1.eval())).i * ((Int)(e2.eval())).i);

}

String toStrng() {

return "(" + e1.toStrng() + " * " + e2.toStrng() + ")";

}

boolean hasZero() {

return e1.hasZero() || e2.hasZero();

}

Exp noNegConstants() {

return new Mult(e1.noNegConstants(), e2.noNegConstants());

}

}

Optional: Multimethods

使用multimethod可以避免使用double-dispatch来实现二元操作(本质上就是方法重载)

使用重载的多个方法,但也存在缺点,容易造成方法调用的混淆。

虽然通过不同子类的参数来重载方法在其他语言很常见,但在ruby中很难做到,主要有两点原因:

(1)首先ruby动态类型语言,没有对方法的参数添加类型限制

(2)其次ruby不允许除了覆写以外的同名函数(同名就意味着覆写override,而不是重载overload)

但在其他静态的面向对象语言中,虽然提供了多种方法重载,但只是静态重载。在编写时需要指定静态类型(尽管运行时仍然动态分派)。但这就与我们课程例子所谓的二元操作关系不大了,因为课程中的两个操作对象,可能是Int、Rational或String,但显然在Java等语言中,这个操作对象的类型是确定的。

C# 4.0中加入了动态类型,因此也能够实现multimethod

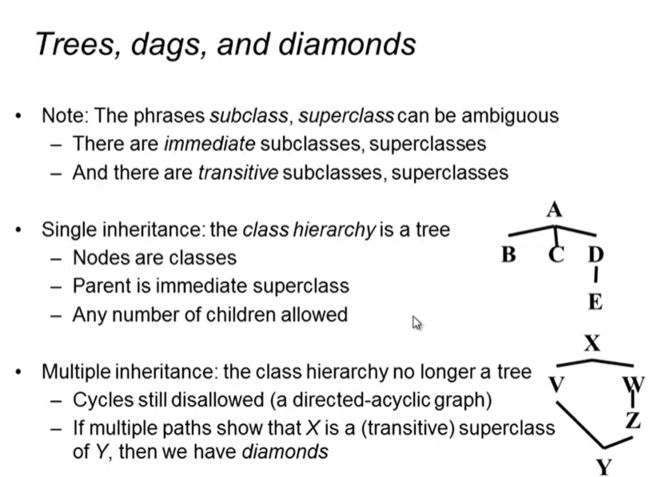

Multiple Inheritance

多继承,也是OOP老生常谈的话题。

多继承的优势和劣势:

继承结构间可能存在歧义:

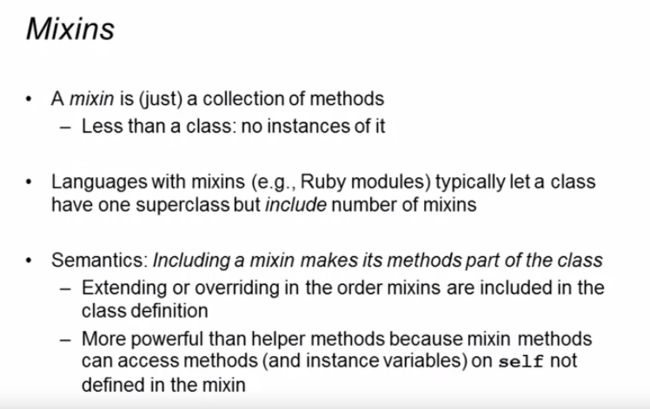

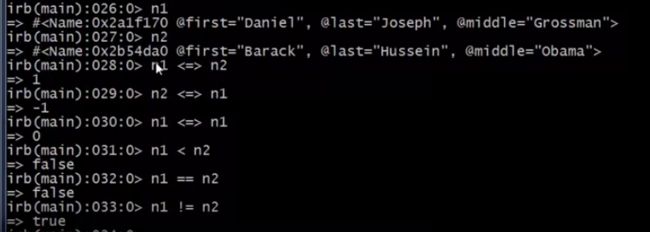

Mixins

mixins是指一个方法的合集,与类的区别在于没有实例。

ruby的modules就是mixins

例子:

mixin的改变了方法的查找规则,先在类中寻找,然后在mixin中寻找,再在超类中寻找,再在超类的mixin中寻找,以此类推。

对于对象变量,mixin方法可能会造成问题:

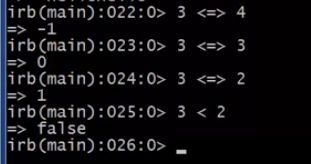

ruby中最有用的两个mixins,Comparable比较和Enumerable枚举。

其中>,<等比较运算符是定义在<=>之上的(即<,>,=等运算调用<=>比较)

其他的迭代器则是定义在each上

例子:

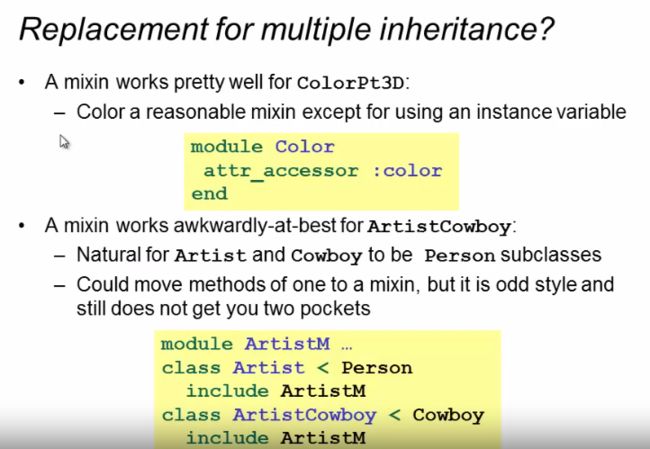

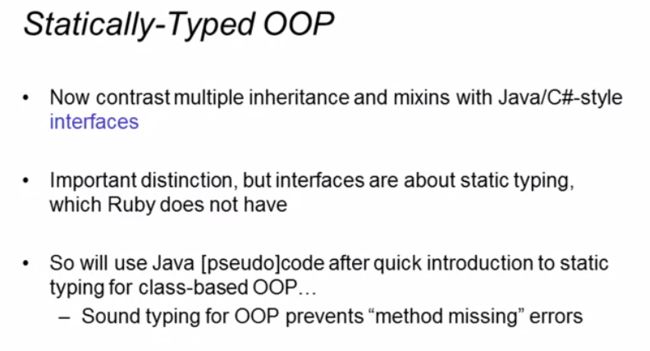

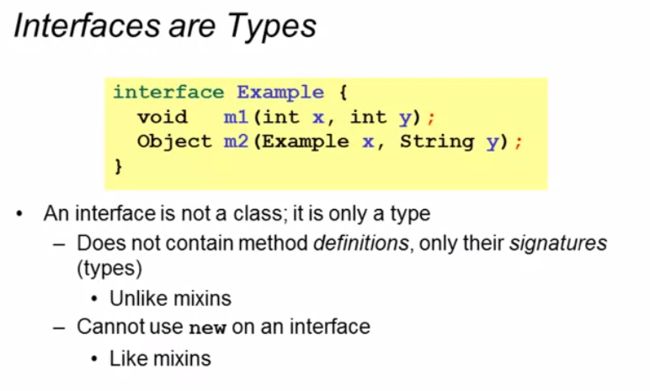

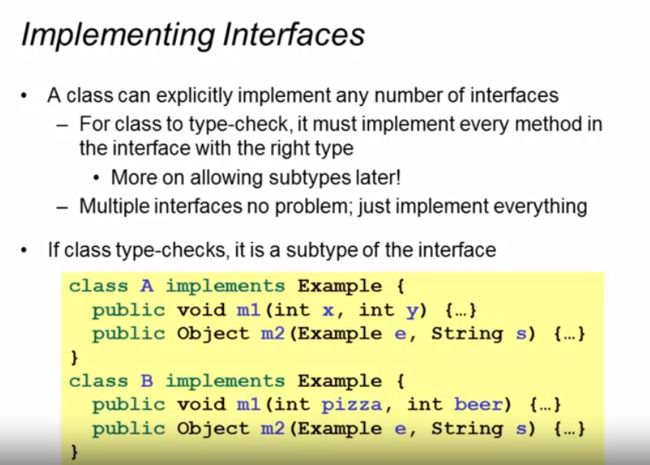

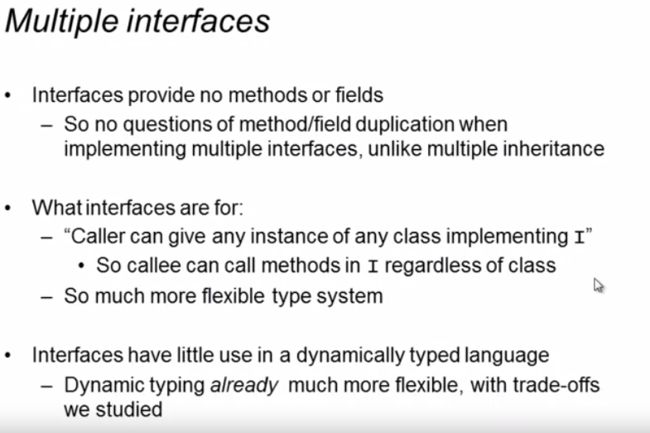

Interfaces

比较多继承与mixins ,和接口的区别

接口的事情学过Java应该都很熟悉了

接口可以与mixins共同使用,保证某些方法一定被类实现(例如Comparable需要实现<=>,Enumerable需要实现each)

Optional: Abstract Methods

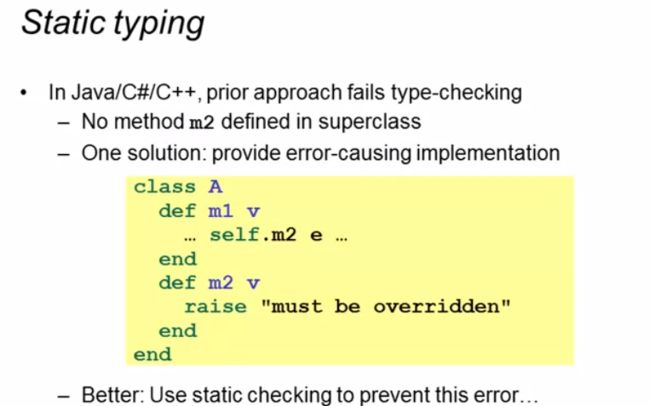

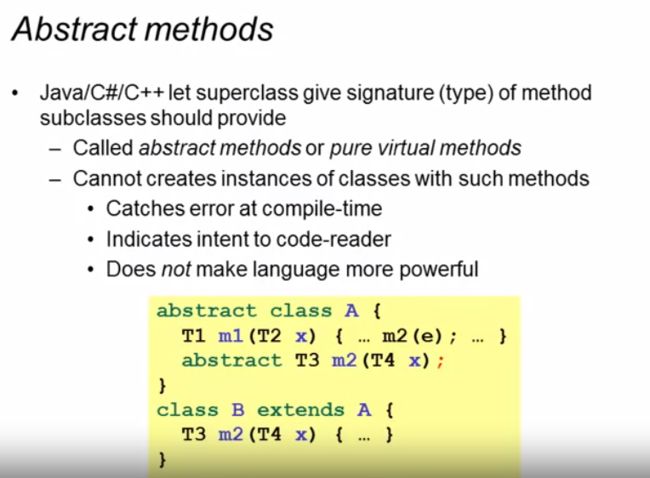

这一节是为了更详细的介绍OOP,所以介绍抽象方法,比如Java的抽象方法和C++的纯虚函数。

一般会存在超类定义了某些子类必须覆写的方法,在Ruby中我们可以(例如下面的例子),我们可以不定义m2,却直接在m1中使用它,此时的m2就是子类必须定义的内容,并且我们不能单独A.new创建A的实例,否则会method-missing。

值得特别注意的是,在静态语言中是不允许这样做的,父类无法调用只在子类中声明定义的方法;ruby是可以在父类中直接调用只在子类声明定义的方法的,总的来说宽松一些(只有运行时才能判断该方法是否被父类或子类定义)。

在静态类型语言中,type chcker会保证m2必须在父类中被声明定义,因此我们需要一些多余的语句(例如下面例子的raise语句部分),这样会非常冗余。

因此有了抽象方法,只声明而不定义,留给子类(每一个子类必须)定义。这样同时也限制了父类的实例创建。

OOP的代码传递与FP的代码传递对比:

OOP的方式:通过子类定义的m2传递到超类的m1中(即使超类m1定义时不会知道m2具体是什么内容,因为m2的定义是运行时才被动态分派的)

FP的方式:高等函数传递代码,高等函数也无法知晓具体内容(例如f中的g,虽然会根据语法认定为函数,但只有运行时才会知晓g具体是什么)。对于定义的f,存在caller(调用者例如h),调用者h提供g的定义,传递到被调用者f中。

总的来说,两者是类似的,都是在超类/callee中定义方法m,这个方法m中包含一些其他方法n(只有运行时才会知道定义的方法),而这个n的定义(额外信息/需要传递的代码)由子类或者caller调用者来提供。

这是一种常用编程手段。

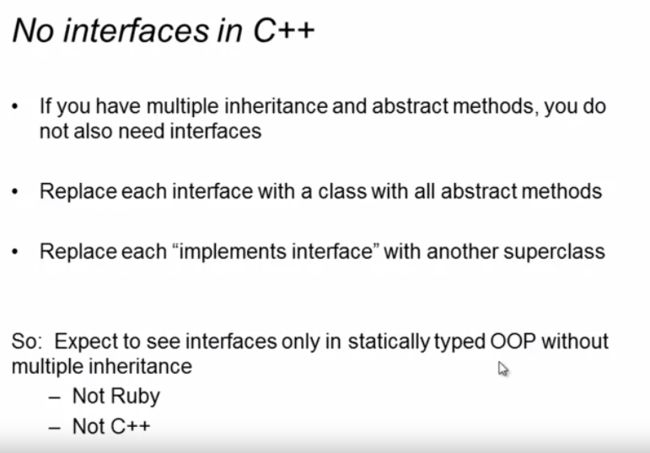

最后讨论没有接口的C++,接口可以通过类与全部抽象方法(纯虚函数)实现,然后接口实现通过类继承(多重继承)来实现。