I Take It All Back: Using Windows Installer (MSI) Rollback Actions

Sometimes an installer just needs to do something that Windows Installer doesn't normally do. When that happens, it's a simple matter of writing a custom action, right? Unfortunately, it's not that simple. In this post, we'll look at techniques for reversing changes made by a custom action.

When you launch an installation, it first runs in what's called immediate mode or script-generation mode. As your installer runs in this immediate mode, it generates an internal to-do list of what it will do on a system—"First I'll install files, then I'll create shortcuts, then I'll write to the registry, and then..."—but doesn't yet make any system changes.

After immediate mode is done, your installer then switches to something called deferred mode or script-execution mode. In deferred mode, your installer performs the actions listed in this script: "Now I'm installing files, now I'm creating shortcuts, now I'm writing to the registry, and now I'm..." (The internal to-do list, or script, is fixed at this point, which is why you can't set property values outside of immediate mode, for example).

As your installer runs in deferred mode, it simultaneously creates a rollback script describing how to undo changes made by the standard actions. While the installer installs files, for example, it adds to the rollback script specific information about what it would have to do to get the system back to its pre-installer state: "To get the system back to how it was, I'd need to remove sample.exe and readme.txt, and also restore the original version of sample.dll that I replaced." (Windows Installer will also temporarily hold on to resources such as files that it needs to restore in case of rollback.) If the installer runs to completion, the rollback script and any cached resources are deleted. But if the installation encounters a fatal error, or if the user cancels the installation during deferred mode, the rollback script runs.

A big reason to use standard Windows Installer actions instead of custom actions is that standard actions handle their own cleanup during uninstallation or rollback. When you use a custom action, Windows Installer has no idea what the executable, DLL, InstallScript, etc., that you used did to the system, and therefore has no idea how to roll back the changes the custom action made. If your deferred custom action makes any system changes, you should create a corresponding rollback action.

Immediate mode actions don't write to the rollback script, which means that immediate-mode actions that make system changes won't get rolled back if the installation fails. This is one of several reasons not to make system changes during immediate mode

(Bonus grammar tip: The noun and adjective are one word, rollback, while the verb is two words, roll back. "If my rollback action runs, it will roll back my changes." An easy trick is to see if it's appropriate to form the past tense by adding -ed: You'd say "rolled back", not "rollbacked", and the present tense would be the same number of words. Same goes for cleanup vs. clean up, setup vs. set up, and so on. Anyway.)

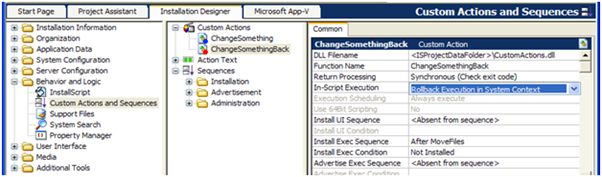

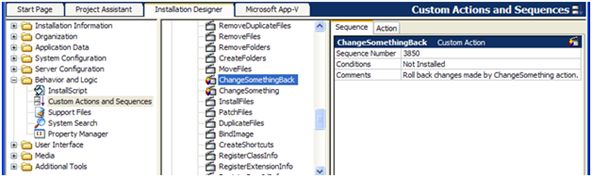

With InstallShield, you mark a custom action as being a rollback action using its In-Script Execution setting.

Because the rollback script is created as deferred execution is taking place, and not beforehand, a rollback action must be placed in the Execute sequence before the action it rolls back. (Anywhere before the action being rolled back is fine, but for readability's sake and other reasons, placing the rollback action immediately before the action it rolls back seems to work best.) If you write a deferred custom action called "ChangeSomething", its corresponding rollback action "ChangeSomethingBack" should appear in the sequences immediately before it.

Double Negatives

Things start to get confusing with uninstallation custom actions. Without a condition, an action always runs, both during the initial installation as well as maintenance mode, including a complete uninstallation. By setting a condition on an action, you can specify during which modes it should run: Not Installed for the initial installation, REMOVE="ALL" for complete uninstallation, and so on.

The same holds for rollback actions. If you have a deferred action that makes system changes during the initial installation, you'll need a rollback action in case the installation fails or the user cancels it. You'll also probably need an uninstallation action that reverses the changes during uninstallation; and also an uninstallation rollback action, in case the uninstallation fails or the user cancels it, and you need to undo whatever you just undid. Luckily, the same condition logic applies: if your deferred uninstallation action uses condition REMOVE="ALL", your uninstall-rollback action can use the same condition.

And Finally...

If your deferred action saves any temporary data—similar to how the InstallFiles action temporarily caches files it might need to restore—your rollback action can clean up that data when it reverses the effects of the original action. But what if the rollback action never runs?

Windows Installer defines yet another type of action, called a commit action, which runs only if the installation successfully runs to completion. If a rollback action runs, a commit action won't run; and if a commit action runs, it's too late for rollback. Defining an action as a commit action in InstallShield also involves the In-Script Execution setting, and follows the same condition logic as other deferred and rollback actions.

To summarize, if you create a custom action that makes changes to a target system, you might wind up making several others to handle rollback, uninstallation, uninstallation rollback, and cleanup. If that's not a good argument for avoiding custom actions that duplicate Windows Installer functionality, I don't know what is.

For more information and some hands-on experience—plus information about how things get trickier with all these deferred, rollback, and commit actions needing to read property values—come visit us at our Advanced Windows Installer (MSI) Using InstallShield Training Course.