多层感知机 分类思想

I spend my working days at a company that builds a social media management platform for charities. We recently conducted user testing on landing pages that advertised our product and kicked off our onboarding process. The idea was to explicitly ‘get across’ what our platform was like prior to having users sign up and actually use the platform. We wanted users to ‘get it’, and understand the advantages of our platform without actually having to use it first (as signing up can be a barrier for some people).

我在一家为慈善机构建立社交媒体管理平台的公司里工作。 我们最近在宣传我们产品并着手启动过程的目标网页上进行了用户测试。 这个想法是在让用户注册并实际使用该平台之前,明确“了解”我们平台的状态。 我们希望用户“获得它”,并了解我们平台的优势,而不必首先使用它(因为注册可能对某些人来说是一个障碍)。

But in testing our advertising and landing pages, we received a lot of comments like:

但是在测试广告和目标网页时,我们收到了很多评论,例如:

“I wanted to know what the tool feels like”

“我想知道该工具的感觉”

“I just want to get to grips with it”

“我只想掌握它”

“I want to just have a bit of a play around”

“我只想玩一玩”

People seemed to want a visceral experience with the tool. We tried clearly explaining what our platform was like in videos, descriptions, and images. We represented the platform and what it does in explicit detail. But it wasn’t enough. The participants had an almost indescribable urge for tangible experience, to know what each step of our tool felt like. They couldn’t put their finger on it, they just needed to use the platform.

人们似乎想要内脏 使用该工具的经验。 我们尝试通过视频,描述和图像清楚地说明我们的平台是什么样的。 我们代表了平台及其明确功能。 但这还不够。 参与者几乎无法形容地渴望获得切实的经验,以了解我们工具每一步的感觉。 他们无法专心致志,只需要使用平台即可。

Why do people feel like this? Why do people need to try out tools to ‘know’ them, even if they’ve seen them represented in explicit detail?

人们为什么会这样? 人们为什么需要尝试工具来“知道”它们,即使他们已经看到它们以明确的细节表示?

We like to think that we are in essence just brains floating ‘outside’ the world as impartial observers, with sensory apparatus like our eyes inputting data that we can process and act upon. We consider our cognition — our ability to understand — to be akin to computer processing.

我们喜欢认为,从本质上讲,我们就像公正的观察者一样,是漂浮在世界“外面”的大脑,像我们的眼睛这样的感觉设备输入了可以处理和作用的数据。 我们认为我们的认知-我们的理解能力-类似于计算机处理。

So, when we talk about our cognition, we say things like “I need to process that”. We analogise the brain as hardware and thoughts as software, as though we are in essence an electronic machine. Importantly, we also consider thinking a linear sequence of perceiving, planning, doing, and interpreting, much like a computer program. We input data into our mind, process it, make a plan, then enact it, and interpret the results. You might call this a ‘computationalist’ theory of mind. Of course, it’s more than a theory, it’s a sociological metaphor. Metaphors are extremely powerful; the philosophers Lakoff and Johnson argue that we understand our world through metaphors.

因此,当我们谈论自己的认知时,我们会说“我需要处理”之类的话。 我们将大脑模拟为硬件,将思想模拟为软件,就好像我们实质上是一台电子机器一样。 重要的是,我们还考虑像计算机程序一样思考感知,计划,执行和解释的线性顺序。 我们将数据输入脑海,进行处理,制定计划,然后制定并解释结果。 您可能将其称为“ 计算论者”心智理论。 当然,这不仅仅是理论,而是社会学的隐喻。 隐喻非常强大。 哲学家拉科夫(Lakoff)和约翰逊(Johnson) 认为 ,我们通过隐喻来理解我们的世界。

Accordingly, a great deal of tools we use have been designed in such a way to reflect this metaphor of our cognition.

因此,我们使用了许多工具,以反映我们认知的这种隐喻。

But we are not computers.

但是我们不是计算机。

The way we go about knowing the world is fundamentally different.

我们了解世界的方式根本 不同 。

We have bodies. We evolved with bodies. We evolved with our environment.

我们有身体。 我们随着身体进化。 我们随着环境的变化而发展。

As our brains are parts of our bodies, they evolved with the rest of our bodies, and alongside our environment as well. Our ability to think wasn’t ‘created’ and it certainly wasn’t ‘created’ with an end goal in mind, such as processing information.

由于我们的大脑是我们身体的一部分,因此它们与我们身体的其他部分以及环境一起进化。 我们的思考能力不是“创造的”,当然也不是“创造”的,其最终目标是考虑到诸如处理信息之类的最终目标。

Think of our cognition, then, as being embodied — as part of our bodies, as a thing that has a context, a materiality, and a history of development. This means our cognition isn’t just thinking with the brain, it’s a systematic whole that involves perceiving and acting in and on the world.

然后,将我们的认知想象为被体现的东西,作为我们身体的一部分,作为具有上下文,物质性和发展历史的事物。 这意味着我们的认识不只是用脑思考,这是一个系统整体,涉及感知 ,并和世界作用 。

Our perception is linked to interpretation — seeing faces in clouds, not noticing changes (‘in-attentional blindness’). Even basic things like recognising shapes, shadows, edges, movement — these are constructed as a perceptive act. We see the world not just subjectively, not just from a different angle as other people, but as a unique, on-the-fly construction. Our perception is attuned to interpret sensory input in a way that constructs meaning, based on past experience and from our biological evolution (we are attuned to recognise faces, for example). But we do not consciously think any of this out — rather, it is anticipatory, immediate, and implicit. Yet it is sensible to say that perception is part of cognition, in that it is a part of how we enact our individualised sense of the world.

我们的感知与解释相关联-在云中看到面Kong,而不是注意到变化(“ 注意力不集中 ”)。 甚至识别形状,阴影,边缘,运动之类的基本事物也被视为感知行为。 我们不仅从主观角度看待世界,而且不仅从与他人不同的角度看待世界,而且将其视为独特的动态结构。 基于过去的经验和我们的生物学进化,我们的感知被调整为以某种方式构造意义的方式来解释感觉输入(例如,我们被调整为识别面部)。 但是,我们不会有意识地想到所有这些,而是预期的,立即的和隐含的。 然而,可以说感知是认知的一部分,这是明智的,因为它是我们实施个人化的世界感的一部分。

We use our actions to alter the world to help us think. We organise our world to help us remember where things are, or that we have to do something: a note by the door; all forks in the drawer by the fridge; clean clothes in that basket not that one. Action reveals, organises and groups — it interacts with how we think about our world. Acting on the world can take the burden off our brain — and in doing so it becomes a cognitive act (the Academic David Kirsch referred to these as ‘epistemic actions’ — actions intended to facilitate information processing rather than pragmatic result).

我们用自己的行动来改变世界,以帮助我们思考。 我们组织世界来帮助我们记住事物在哪里,或者我们必须做些事情:门旁的纸条; 冰箱里抽屉里的所有叉子; 干净的衣服在篮子不就是一个。 行动揭示,组织和分组-它与我们对世界的看法互动。 对世界采取行动可以减轻大脑的负担,并因此而成为一种认知行为(学者戴维·基尔希(David Kirsch)称这些为“ 认知行为 ” —旨在促进信息处理而不是务实结果的行为)。

These two elements — action and perception — are tied very closely to one another as well. The philosopher Merleau-Ponty gave the example of a blind man using a long stick to help him navigate his world through touch. The stick becomes ‘transparent’ to the man — he stops being aware of the stick as a separate object in space, but instead his focus is on how the stick interacts with objects in space. Perception and action are intertwined in an act of cognition.The same is true of all objects we interact with when we use them as tools, as well as our bodies.

行动和感知这两个要素也彼此紧密联系在一起。 哲学家梅洛-庞蒂(Merleau-Ponty)举例说明了一个盲人用长棍棒帮助他通过触摸来导航自己的世界。 棍子变得对男人是“透明的”-他不再意识到棍子是空间中的独立对象,而是专注于棍子与空间中的物体如何相互作用。 知觉和行动在认知行为中交织在一起,当我们将它们用作工具时与我们互动的所有物体以及我们的身体也是如此。

So, let’s start a sentence that builds on this point:

因此,让我们开始基于这一点的句子:

Perceiving and action are part of cognition.

感知和行动是认知的一部分。

Great. But it isn’t just that action and perception are a part of cognition, they are creative acts that feedback into themselves.

大。 但是,不仅行动和感知是认知的一部分 ,它们还可以是反馈给自己的创造性行为。

It’s perhaps easiest to understand this by comparing our cognition to a computer’s processing. You don’t plan your actions then enact them robotically the way a computer would. You just act , you just perceive— your actions aren’t analogous to you explicitly thinking: “Now I’m going to look to my left; next, I’ll reach over with my left hand to grasp a magazine”. While we are aware to varying degrees of how our body is engaged with the world, we are to a greater degree reflecting on wants, desires, feelings, etc, and that output of manifests as actions and perception. Ours is a generalised intent rather than a specific plan.

通过将我们的认知与计算机的处理进行比较,可能最容易理解这一点。 您不打算计划自己的动作,而是按照计算机的方式自动执行这些动作。 您只是采取行动 ,就只是感觉到了 —您的行动与您明确思考的方式并不相似:“现在,我要向左看; 接下来,我将用左手拿起杂志。” 尽管我们在不同程度上了解我们的身体与世界的互动方式,但我们在更大程度上反映了需求,欲望,感觉等,以及作为行动和知觉的表现形式。 我们的目标是广义的,而不是具体的计划。

What’s more, as you act/perceive, the feedback from you doing it informs the next action/perception activity you undertake. Think how you explore what you are saying as you are saying it; when you are drawing, the act of drawing helps you to understand the shape and detail of the drawing as you are drawing it. Each action is an expression of cognition, of what you are thinking. Each act is a feedback loop that is inseparable from the next act. We do something and in that doing we learn more about what we are doing.

而且,当您采取行动/感知时,您所做的反馈会告知您进行的下一个行动/感知活动。 以为你有多么探索你在说什么,你说的是; 当您绘制,绘图的行为可以帮助你了解图形的形状和细节, 为你绘制它。 每个动作都是对您所想的认知的表达。 每个动作都是与下一个动作不可分割的反馈回路。 我们做某事,并且在此过程中,我们会更多地了解自己在做什么。

The anthropologist/philosopher Lambros Malafouris has argued that, in this way, cognition cannot be divided from our world “‘material culture is potentially co-extensive and consubstantial with the mind”.

人类学家/哲学家兰弗罗斯·马拉弗里斯(Lambros Malafouris)认为,通过这种方式,认知不能与我们的世界区分开:“' 物质文化可能与思想共存并具有实质性意义 '。

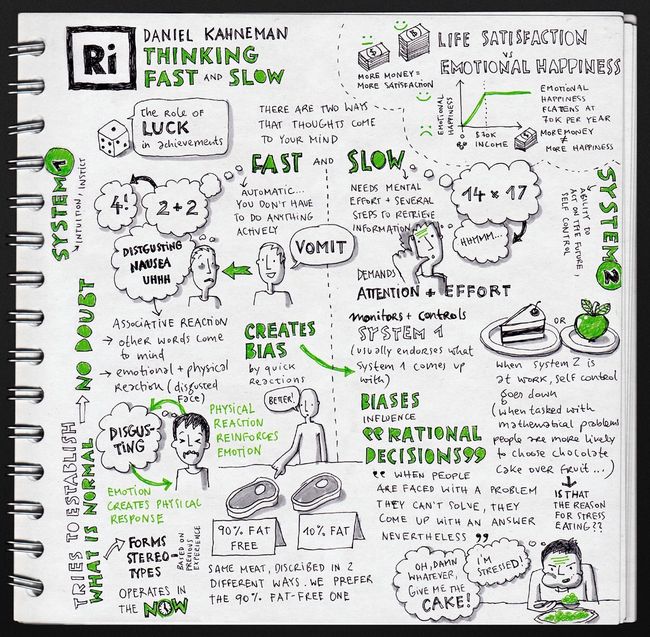

So, normally, our immediate actions aren’t explicit. They are responsive, instinctual, implicit activity — more of a vague intention that a plan. Much like Daniel Kahneman’s System 1 thinking, we act and perceive without carefully modelling each activity we are going to do, and then planning how each activity is going to ‘run’ on the world. We just perceive and act to help us create an understanding.

因此,通常情况下,我们的直接行动并不明确。 他们是响应式,本能的,隐性的活动-比计划更含糊。 就像丹尼尔·卡尼曼(Daniel Kahneman)的System 1思维一样 ,我们在进行行为和感知时无需仔细建模要进行的每个活动,然后计划每个活动如何在世界上“运行”。 我们只是感知并采取行动来帮助我们建立理解。

Eva-Lotta Lamm Eva-Lotta LammThis gets very abstract in certain actions which seemingly have no relation to what we are thinking about. Think about gesturing — people think it’s a way of communicating, but that’s very often not the case. Blind people gesture, for example.

在某些似乎与我们所考虑的内容无关的动作中,这变得非常抽象。 考虑一下手势–人们认为这是一种沟通方式,但通常并非如此。 例如,盲人手势。

This is why my research participants earlier couldn’t specify exactly what they meant — it’s very challenging to express how the combination of action and perception can help you understand things. It’s an intuitive understanding that isn’t just about impartially observing how things work, but implicitly understanding a process or tool by conducting a sort of acting/perceiving loop upon it. And it’s worth noticing that this is different from ‘practice’ — practice is about improving on an existing knowledge base, not creating an initial experience of embodied knowledge.

这就是为什么我的研究参与者先前无法确切说明其含义的原因-表达行动和感知的结合如何帮助您理解事物是非常具有挑战性的。 这是一种直观的理解,不只是公正地观察事物的工作方式,而是通过对过程或工具进行某种行为/感知循环来隐式地理解过程或工具。 值得注意的是,这与“实践”不同-实践是在现有的知识基础上进行改进,而不是创建体现知识的初始体验。

Let’s update that sentence:

让我们更新一下这句话:

Perceiving and action are an embodied part of our cognition that helps us intuitively create an implicit understanding of our world.

知觉和行动是我们认知的内在组成部分, 它帮助我们直观地建立对世界的隐性理解 。

But of course, we can’t just create a world to understand out of nothing. Our world only allows for explorations that ‘afford’ it. This idea was pioneered by JJ Gibson who also coined the term ‘affordances’. Affordance, in his reckoning, simply meant a situation that enabled a possibility for for action. A stick can be used to hit someone with, or to point with, or a sensory tool for our previously mentioned blind friend. But different objects afford different actions better than others. Stairs afford stepping given their shape — you would be hard pressed to do something like lie down on them, a bed would afford that much more effectively. Affordances don’t even require our awareness: a hole can be used to hide in, but it can also be fallen into by the unawares.

但是,当然,我们不能仅仅创造一个无所不能的世界。 我们的世界只允许“承受”它的探索。 这个想法是由吉布森(JJ Gibson)提出的,他也创造了“ 赠品 ”一词。 在他看来,负担是指可以采取行动的情况。 可以使用一根棍子用我们前面提到的盲人朋友用感官工具击中或指点某人。 但是不同的对象比其他对象提供更好的动作。 楼梯具有一定的形状,因此可以承受踩踏的麻烦-很难像在他们身上躺下来那样做,床可以更有效地承受这种情况。 负担甚至不需要我们意识到:一个洞可以用来躲藏,但也可以被无意识的人掉进去。

The handles affords a specific type of grasping 手柄提供特定的抓握类型Again, let’s update that sentence:

再次,让我们更新该句子:

Perceiving and action are an embodied part of our cognition that helps us intuitively create an implicit understanding of our world through affordances.

知觉和行动是我们认知的内在组成部分,它帮助我们通过负担能力直观地建立对世界的隐性理解。

So taking us back to our original question: we need to act and perceive to help us create an understanding of our world through affordances. And when we do, it’s often implicit action formed through generalised intentions rather than plans. And of course, these can only happen through affordances. This is what my research participants wanted to do.

因此,让我们回到最初的问题:我们需要采取行动和感知,以帮助我们通过能力来建立对世界的了解。 而当我们这样做时,它通常是通过广义意图而不是计划形成的隐式行动。 当然,这些只能通过能力来实现。 这是我的研究参与者想要做的。

There’s a problem in all this however.

但是,这一切都有问题。

The problem is that computers and the software on it are designed for people who act like computers. Obviously this was worse in the past, but it still remains.

问题在于,计算机及其上的软件是为像计算机一样工作的人设计的。 显然,这在过去更糟,但仍然存在。

We still ask users to create mental models of information and interaction structures that they can’t possibly grasp without significant experience with our products. And people find it difficult, or at best laborious, to understand the situation that doesn’t reveal itself through the kind of embodied cognition discussed. We force users to build representations and then make them navigate those representations in their mind to understand how an interaction would work. We force them to model it rather than generate implicit understanding through embodied cognition.

我们仍然要求用户创建信息和交互结构的思维模型,如果没有丰富的产品经验,他们将无法掌握这些模型。 人们发现,很难通过讨论的内在认知来了解无法揭示自己的情况 ,或者充其量是费力的。 我们强迫用户构建表示形式,然后使他们在脑海中浏览这些表示形式,以了解交互将如何工作。 我们强迫他们为它建模,而不是通过具体化的认知来产生内隐的理解。

It’s much easier to define a structure that expects a person to linearly process concepts rationally into a whole than to apply concepts of intuitive understand through perception/feedback loops, as I’ve discussed.

正如我已经讨论过的,定义一个期望一个人将一个概念合理地线性处理成一个整体的结构要比通过感知/反馈循环应用直观理解的概念容易得多。

But the divide of the world into perceiving, thinking and doing is a false one, or at least false enough that it has harmed the efficacy of digital products. This division between perceiving, thinking and doing is an artefact of the society and culture we find ourselves in. There’s no reason it has to be this way. It’s just the computer metaphor.

但是,将世界分为感知,思考和做事是错误的,或者至少是错误的,以至于损害了数字产品的功效。 感知,思考和做事之间的这种区分是我们所处的社会和文化的产物。没有必要这样做。 这只是计算机的隐喻。

To be fair, it can be very difficult to create an embodied learning within the realm of digital products. HCI academic Paul Dourish touched on this in his book, Where the Action is. He notes that we implicitly ‘couple’ with things in our world (like a hammer) to get things done through affordances, but it’s very difficult to parse how we ‘couple’ with digital technologies because of the many layers of abstraction. In this way, it can be difficult to parse where the embodied action ‘lies’.

公平地讲,在数字产品领域内创建一个具体的学习可能非常困难。 HCI学者Paul Dourish在他的著作《行动在哪里》中谈到了这一点 。 他指出,我们隐式地“耦合”世界上的事物(例如锤子)以通过负担来完成任务,但是由于抽象的许多层面,很难解析我们如何与数字技术“耦合”。 这样,可能难以解析所体现的动作“所在”的位置。

Still, there is a lot we can do to allow for — so let’s remember our sentence and look at some examples of how to implement it:

尽管如此,我们仍然可以做很多工作-因此,让我们记住我们的句子,并查看一些有关如何实现它的示例:

Perceiving and action are an embodied part of our cognition that helps us intuitively create an implicit understanding of our world through affordances.

感知和行动是我们认知的体现部分,可帮助我们通过能力来直观地建立对世界的隐性理解。

Allow for guided doing

允许进行指导

Computers and touchscreens are notoriously poor at providing clear affordance of action, given that screens are not tangible in any real sense, and are buried under layers of abstraction and interface. What I call ‘guided doing’ is the act of helping to create an intuitive understanding. By gently guiding someone through an action we allow them to understand the situation and how they are embodied in it.

众所周知,由于屏幕在任何实际意义上都不是有形的,并且掩埋在抽象和界面层之下,因此计算机和触摸屏在提供清晰的动作方面非常差。 我所谓的“指导性做事”是帮助建立直觉理解的行为。 通过轻轻地指导某人进行某项操作,我们可以使他们了解情况及其在其中的体现。

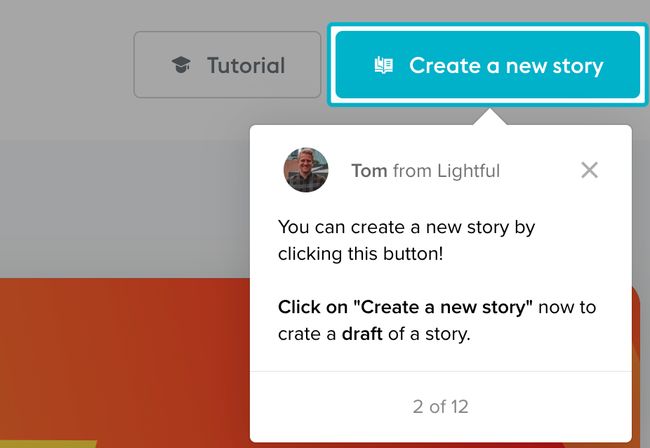

You can see this in product tours — ours here as an example:

您可以在产品浏览中看到这一点-以我们的示例为例:

We at Lightful created gentle, stepwise product tours that got users to take the steps to connect their social media accounts and create draft posts. While some users closed the tour, a good portion of our users continued through it. New users who went through the tour posted more using our platform by quite a large margin.

我们在Lightful创建了温和的,逐步的产品导览,使用户能够采取步骤来连接其社交媒体帐户并创建草稿。 尽管一些用户关闭了导览,但我们的很大一部分用户仍继续浏览。 游览的新用户使用我们的平台发布了更多信息。

Product tours are not perfect because it’s not just an implicit action-response the user undertakes. Instead users are required to read and ascribe an embodied meaning of the action through words, rather than just through action. However, product tours help by normally blocking out parts of the screen, and focussing on a single step in a way where perceiving and acting are the key activities, rather than explicit thinking. The objective of product tours is not just ‘showing rather than telling’, it’s requiring users to practice actions, integrating intuitive, visceral understanding of the rhythms, affordances and feedback of the product.

产品浏览并不是完美的,因为它不仅仅是用户执行的隐式操作响应。 取而代之的是,要求用户通过单词而不是仅仅通过动作来阅读和赋予动作的具体含义。 但是,产品浏览可以通过通常遮挡屏幕的某些部分,并以感知和行动是关键活动而不是外在思考的方式专注于单个步骤来提供帮助。 产品浏览的目的不仅仅是“展示而不是讲”,它要求用户练习操作,整合对产品的节奏,能力和反馈的直观,内在的理解。

At Lightful, we tried explaining our our product , as though that would be sufficient — ‘if they can read about it then they understand it’, we thought. But this wasn’t nearly as effective as just getting someone to use the product in a way that embodied their understanding.

在Lightful,我们试图解释我们的产品,好像就足够了–我们认为,“如果他们能读懂它,那么他们就会理解它”。 但这远不及让某人以体现他们理解的方式使用产品有效。

Words can be interpreted very differently. Semantics can’t communicate the implicit, embodied knowledge that embodied cognition brings. And this is vital for someone knowing and liking a product. When we got people to use our product with product tours the knowledge they received was unambiguous — there was an intuitive understanding framed by semantics.

单词的解释可能非常不同。 语义学无法传达认知所带来的隐含知识。 这对于了解和喜欢产品的人至关重要。 当我们让人们将产品用于产品旅行时,他们所获得的知识是明确的-语义框架构成了一种直观的理解。

Abstracted play

抽象播放

Abstracted play is the divorcing of the UI layer — the ‘noise’ — from the page to get the user to focus on what is relevant in a simplified, abstracted way.

抽象游戏是将UI层(“噪音”)与页面分离开来,以使用户集中精力以简化的抽象方式关注相关内容。

You can see how Trello does this by creating a simple wireframe of their site and describing in simple words how to use their product. This is part of their onboarding process, in which people are still understanding the affordances.

您可以通过在其网站上创建一个简单的线框并用简单的文字描述如何使用其产品来了解Trello的工作方式。 这是他们入职过程的一部分,在此过程中,人们仍在理解这些能力。

Trello’s efforts brings affordances into clear view. The perceiving and acting become very simple. Our perception-action-cycle isn’t overwhelmed, trying to make meaning and finding affordances in a busy UI — it’s stripped back so the perception-action is straightforward.

Trello的努力使负担能力变得清晰可见。 感知和行动变得非常简单。 我们的感知-行动周期并没有被淹没,而是试图在繁忙的用户界面中表达自己的意思并找到可承受的东西–它被剥离了,因此感知-行动很简单。

What’s more, the user can see the result of their action in a highly visible manner. As they type, they see the names appear on the Trello columns to the right.

而且,用户可以以高度可见的方式看到其动作的结果。 输入时,他们会看到名称出现在右侧的Trello列中。

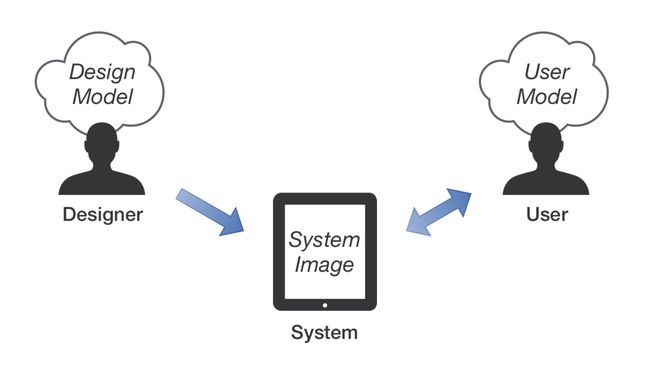

You might call this making the ‘system image’ clearer in Don Norman’s mental model structure.

您可以称其为Don Norman的心理模型结构中的“系统形象”更加清晰。

However we aren’t asking the user to understand ‘system image’ explicitly. The perception/action loop is doing the work. Much like the blind man with the stick, the more ‘transparent’ you can make the correlation between the instrument and the effect, the better the embodied the understanding will be.

但是,我们并没有要求用户明确理解“系统映像”。 感知/动作循环正在完成工作。 就像盲人用棍子一样,使乐器和效果之间的关联越“透明”,对理解的体现就越好。

Microinteractions

微交互

There are so many microinteractions that do nothing to give the user an indication of what is happening. Rather, they look flashy, and pat a visual designer’s ego. Sure, some of them add an aesthetic flair, but many actually get in the way of an embodied understanding. Take a look over at Dribbble for some over-engineered animated microinteractions (I won’t place any here so as not to insult anyone).

太多的微交互作用无济于事,无法向用户表明正在发生的事情。 相反,它们看起来浮华,并轻拍了视觉设计师的自我。 当然,其中一些增加了美学特质,但实际上许多阻碍了具体化的理解。 看一下Dribbble,了解一些过度设计的动画微交互(我不会在这里放置任何东西,以免侮辱任何人)。

Microinteractions should work as signifiers, affordances or feedback. Material design is an aspect of a larger system of microinteractions.

微交互应充当指示符,能力或反馈。 材料设计是较大的微交互系统的一个方面。

As the material guidelines state

如材料指南所述

“Motion focuses attention and maintains continuity, through subtle feedback and coherent transitions. As elements appear on screen, they transform and reorganize the environment, with interactions generating new transformations.”

“运动通过微妙的反馈和连贯的过渡来集中注意力并保持连续性。 当元素出现在屏幕上时,它们将转换并重新组织环境,并通过交互产生新的转换。”

Of course, material design isn’t a microinteraction, it’s more of a design system, but it contains a number of useful microinteractions. These include panels and drawers ‘swiping’ ‘in’ and ‘out’. The user can interact and get immediate feedback which then feeds into future actions.

当然,材料设计不是微交互,它更像是一个设计系统,但是它包含许多有用的微交互。 这些包括面板和抽屉“向内滑动”,“向内滑动”。 用户可以进行交互并立即获得反馈,然后反馈给将来的操作。

The problem with material design is that it not always clear what affords what. Can you swipe everything? How do things that slide offscreen re-appear? Affordances, we remember, are possibilities for action.

材料设计的问题在于,并不总是清楚什么能提供什么。 你可以刷一切吗? 滑出屏幕的东西如何重新出现? 我们记得,负担能力是采取行动的可能性。

The best microinteractions are those that are visible, have a clear affordance, and clear feedback when interacted with. Scroll bars are so successful because they require only perceiving and acting to understand. If you didn’t know how scroll bars worked, you could intuit it through action and perception: the scroll bar moves as you go up and down the screen.

最好的微交互是那些可见的,具有清晰的承受能力和与之交互时清晰的反馈的交互。 滚动条之所以如此成功,是因为它们只需要感知和行动就可以理解。 如果您不知道滚动条是如何工作的,则可以通过动作和感知来感知它:滚动条在屏幕上上下移动。

Don’t require people to build a model of how things work

不需要人们建立事物运作的模型

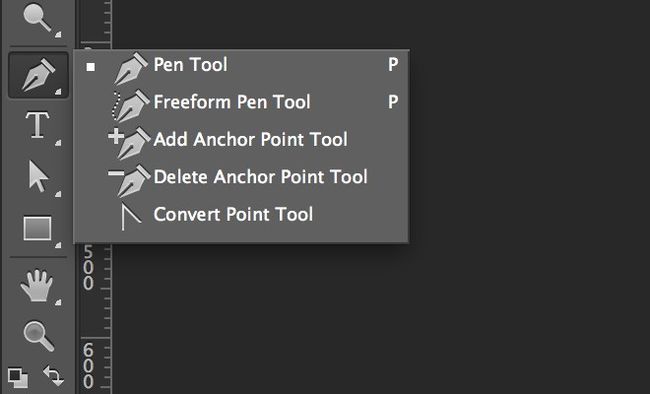

In the past 10 years or so, new digital creative tools have overwhelmed existing legacy tools. Adobe and Microsoft’s tools and many other older legacy software tools have been pushed from the spotlight. Sketch and Figma have replaced Illustrator and Photoshop in many areas. Keynote and Google Slides have shown Powerpoint the door. And so on.

在过去的十年左右的时间里,新的数字创意工具已经淹没了现有的传统工具。 Adobe和Microsoft的工具以及许多其他较旧的旧版软件工具已受到关注。 Sketch和Figma在许多领域都取代了Illustrator和Photoshop。 主题演讲和Google幻灯片向Powerpoint显示了大门。 等等。

Why?

为什么?

Legacy tools have an underlying structure that belies how they see the user: as a computer, as a non-embodied cognitive agent.

传统工具的基本结构掩盖了他们如何看待用户:作为计算机,作为非具体化的认知代理。

These tools have many modes, invisible to the user. They don’t clearly reveal a user’s action. They overwhelm with unclear affordance in their UIs. They require that a user be taught how the symbolic creates an action (rather than just affording action), and how the model of all of the actions work with one another. It’s a significant cognitive overhead for the user that, in the past, engineers would claim is necessary.

这些工具具有许多用户看不见的模式。 它们没有明确显示用户的操作。 他们在用户界面中负担不清,因此不知所措。 他们要求教给用户符号如何创建一个动作(而不只是提供动作),以及所有动作的模型如何相互配合。 过去,工程师认为这对用户来说是很大的认知负担。

You may argue “But I get Illustrator, it’s so simple”. Well, it’s likely because you have been trained, or watched videos about it, or Googled a great deal to understand the interplay of the modes, settings, tools symbols etc. You cannot pick it up and start using effectively like you would a hammer, Sketch, or Figma.

您可能会争辩说“但是我得到了Illustrator,它是如此简单”。 嗯,可能是因为您已经受过培训,或者观看了有关它的视频,或者用Google搜索了很多有关模式,设置,工具符号等的相互作用的信息。您无法像锤子一样捡起它并开始有效地使用它,草图或Figma。

This symbolic knowledge is predicated on a lot of pre-existing learning 这种象征性的知识是基于许多现有的学习It’s increasingly clear that good design must incorporate a sense of embodied cognition to make tools more immediately useful and usable.

越来越清楚的是,良好的设计必须包含一种内在的认知能力,以使工具更直接地变得有用和可用。

But this principle far far, from the ‘less UI is better’ canard. Indeed, less UI can often hide affordance, make it very difficult for a user to get an embodied understanding of a tool — everything becomes invisible and hidden.

但是这个原则离“越少UI越好”的标准就差得远了。 实际上,更少的UI常常可以隐藏可负担性,这使用户很难对工具进行具体的理解-一切都变得不可见和隐藏。

Remember how we were talking about how distinguishing between thought and action was a fool’s errand? Well this should be reflected in tools. If I want to do something, it should just happen in a way where the goal is what is relevant, not the tool to use the achieve goal (ready-to-hand in Heideggerian terminology).

还记得我们在谈论如何将思想和行动区分开是傻瓜的事吗? 好吧,这应该反映在工具中。 如果我想做某事,它应该以与目标相关的方式发生,而不是使用达到目标的工具(海德格尔术语中的现成方法 )。

Context sensitivity, awareness of skill level, feedback, and consistent, predictable patterns can all help. When I act, there should be a clear reaction to my actions because I will attempt to both implicitly and explicitly make meaning of my actions regardless — and we should use that to help a user to understand. We shouldn’t ask them to build an enormous, complicated mental model of our tool, then shove them out into it. We should let them poke at it, and show what happens when they do. In that way, the tool can reveal itself to them through an embodied understanding.

上下文敏感性,技能水平意识,反馈以及一致,可预测的模式都可以提供帮助。 当我采取行动时,应该对我的行为做出明确的React,因为无论如何我都会尝试隐式和显式地理解我的行为的含义,我们应该使用它来帮助用户理解。 我们不应该要求他们为我们的工具建立一个庞大而复杂的思维模型,然后再将它们推入其中。 我们应该让他们戳一下,并说明他们这样做时会发生什么。 这样,该工具可以通过具体的理解向他们展示自己。

One of the most basic features in Sketch, for example is by pressing CTRL, you can visually see how elements interact, their space, their alignment to one another:

例如,通过按CTRL键,Sketch是最基本的功能之一,您可以直观地看到元素之间的交互方式,它们的空间以及它们之间的对齐方式:

There’s no question as to what’s happening — spaces are shown and by moving objects we can see line length and space change. A user does not have to imbibe an entire mental model to understand this interaction.

毫无疑问,这是怎么回事—显示了空格,通过移动对象,我们可以看到线长和空格的变化。 用户不必吸收整个心智模型来理解这种交互。

There’s certainly some highly technical tools where embodied interaction is difficult. Obviously, an aircraft controller won’t be able to poke and prod her away around tools in an embodied way — the entire mental model needs to be understood prior to using the tool. That, however, does not mean that the learning methods for the tool can not be embodied.

当然,在某些高度技术化的工具中,难以实现具体的交互。 显然,飞机控制员将无法以一种具体的方式来戳戳和刺探她-在使用工具之前,必须先了解整个心理模型。 但是,这并不意味着不能体现该工具的学习方法。

The fallacy of separating the mind from the body has a lot of pernicious effects. Crappy digital products are probably the least of the problems associated with it. Still, starting from the ground up can change cultural practices on deeper levels. So, when designing something interactive, ask yourself these questions:

将思想与身体分离的谬论有很多有害影响。 糟糕的数字产品可能是与此相关的问题中最少的。 但是,从头开始可以在更深层次上改变文化习惯。 因此,在设计交互性内容时,请问自己以下问题:

How can I embody the user’s actions?

如何体现用户的行为?

How can I ensure that users don’t need to fill in the gaps of an interaction model in their mind, and instead represent it all onscreen?

如何确保用户不需要填补交互模型中的空白,而是将其全部呈现在屏幕上?

How can I make feedback as reactive as possible to action?

如何使反馈对行动尽可能React灵敏?

How can I ensure each action leads to a better understanding of the next action?

如何确保每个动作都能更好地理解下一个动作?

How could I build my tool in such a way that a user who couldn’t read would understand it?

如何以一种不会阅读的用户能够理解的方式构建我的工具?

And we’ll all be well on our way to a more embodied word.

而且,我们都会在实现一个更加具体化的单词的过程中保持良好状态。

If you like this article, check out my newsletter that explores how technologies change who we are: https://disassemble.substack.com/

如果您喜欢本文,请查看我的新闻通讯,该通讯探讨技术如何改变我们的身份: https : //disassemble.substack.com/

翻译自: https://medium.com/swlh/perceiving-and-acting-are-forms-of-thought-product-design-needs-to-recognise-this-df4a70148c04

多层感知机 分类思想