Go语言实现23种设计模式的使用

前言

设计模式是软件工程中各种常见问题的经典解决方案,本文主要介绍了Go语言实现23种设计模式的使用,文中通过示例代码介绍的非常详细,对大家的学习或者工作具有一定的参考学习价值,需要的朋友们下面随着小编来一起学习学习吧

介绍

设计模式是软件工程中各种常见问题的经典解决方案,设计模式不只是代码,而是组织代码的方式。假设一行行的代码是砖,设计模式就是蓝图。

设计模式有6大原则,以上的设计模式目的就是为了使软件系统能达到这些原则:

开闭原则

软件应该对扩展开放,对修改关闭。

对系统进行扩展,而无需修改现有的代码。这可以降低软件的维护成本,同时也增加可扩展性。

里氏替换原则

任何基类可以出现的地方,子类一定可以出现。

里氏替换原则是对开闭原则的补充,实现开闭原则的关键步骤就是抽象化,基类与子类的关系就是要尽可能的抽象化。

依赖倒置原则

面向接口编程,抽象不应该依赖于具体类,具体类应当依赖于抽象。

这是为了减少类间的耦合,使系统更适宜于扩展,也更便于维护。

单一职责原则

一个类应该只有一个发生变化的原因。

一个类承载的越多,耦合度就越高。如果类的职责单一,就可以降低出错的风险,也可以提高代码的可读性。

最少知道原则

一个实体应当尽量少地与其他实体之间发生相互作用。

还是为了降低耦合,一个类与其他类的关联越少,越易于扩展。

接口分离原则

使用多个专门的接口,而不使用高耦合的单一接口。

避免同一个接口占用过多的职责,更明确的划分,可以降低耦合。高耦合会导致程序不易扩展,提高出错的风险。

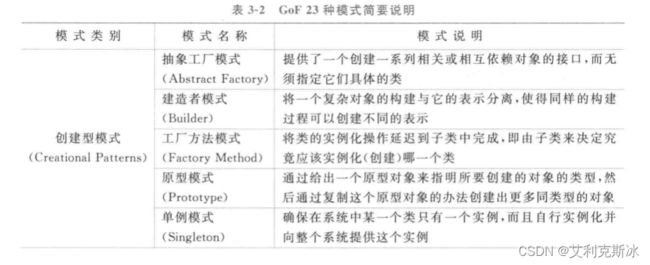

创建型模式

创建型模式是处理对象创建的设计模式,试图根据实际情况使用合适的方式创建对象,增加已有代码的灵活性和可复用性。

单例模式 Singleton

问题

存储着重要对象的全局变量,往往意味着“不安全”,因为你无法保证这个全局变量的值不会在项目的某个引用处被覆盖掉。

对数据的修改经常导致出乎意料的的结果和难以发现的bug。我在一处更新数据,却没有意识到软件中的另一处期望着完全不同的数据,于是一个功能就失效了,而且找出故障的原因也会非常困难。

一个较好的解决方案是:将这样的“可变数据”封装起来,写一个查询方法专门用来获取这些值。

单例模式则更进一步:除了要为“可变数据”提供一个全局访问方法,它还要保证获取到的只有同一个实例。也就是说,如果你打算用一个构造函数创建一个对象,单例模式将保证你得到的不是一个新的对象,而是之前创建过的对象,并且每次它所返回的都只有这同一个对象,也就是单例。这可以保护该对象实例不被篡改。

解决

单例模式需要一个全局构造函数,这个构造函数会返回一个私有的对象,无论何时调用,它总是返回相同的对象。

请看以下代码:

饿汉模式: 程序运行时进行初始化

package main

import "fmt"

type singleton struct {

}

var instance *singleton

func init() {

if instance == nil {

instance = new(singleton)

fmt.Println("创建单个实例")

}

}

// 提供获取实例的方法

func GetInstance() *singleton {

return instance

}

懒汉模式: 当方法首次被调用时进行从初始化

package main

import (

"fmt"

"sync"

)

//单例类

type singleton struct {

value int

}

//声明私有变量

var instance *singleton

var once sync.Once

func GetInstance() *singleton {

once.Do(func() {

instance = new(singleton)

fmt.Println("创建单个实例")

})

return instance

}

单例实例singleton被保存为一个私有的变量,以保证不被其他包的函数引用。

用构造方法GetInstance可以获得单例实例,函数中使用了sync包的once方法,以保证实例只会在首次调用时被初始化一次,之后再调用构造方法都只会返回同一个实例。

测试代码:

func main() {

for i := 0; i < 3; i++ {

GetInstance()

}

}如果你需要更加严格地控制全局变量,这确实很有必要,那么就使用单例模式吧。

工厂方法模式 Factory Method

问题

假设我们的业务需要一个支付渠道,我们开发了一个Pay方法,其可以用于支付。请看以下示例:

| 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 |

type Pay interface { Pay() string } type PayReq struct { OrderId string // 订单号 } func (p *PayReq) Pay() string { // todo fmt.Println(p.OrderId) return "支付成功" } |

如上,我们定义了接口Pay,并实现了其方法Pay()。

如果业务需求变更,需要我们提供多种支付方式,一种叫APay,一种叫BPay,这二种支付方式所需的参数不同,APay只需要订单号OrderId,BPay则需要订单号OrderId和Uid。此时如何修改?

很容易想到的是在原有的代码基础上修改,比如:

| 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 |

type Pay interface { APay() string BPay() string } type PayReq struct { OrderId string // 订单号 Uid int64 } func (p *PayReq) APay() string { // todo fmt.Println(p.OrderId) return "APay支付成功" } func (p *PayReq) BPay() string { // todo fmt.Println(p.OrderId) fmt.Println(p.Uid) return "BPay支付成功" } |

我们为Pay接口实现了APay() 和BPay() 方法。虽然暂时实现了业务需求,但却使得结构体PayReq变得冗余了,APay() 并不需要Uid参数。如果之后再增加CPay、DPay、EPay,可想而知,代码会变得越来越难以维护。

随着后续业务迭代,将不得不编写出复杂的代码。

解决

让我们想象一个工厂类,这个工厂类需要生产电线和开关等器具,我们可以为工厂类提供一个生产方法,当电线机器调用生产方法时,就产出电线,当开关机器调用生产方法时,就产出开关。

套用到我们的支付业务来,就是我们不再为接口提供APay方法、BPay方法,而只提供一个Pay方法,并将A支付方式和B支付方式的区别下放到子类。

请看示例:

| 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 |

package factorymethod import "fmt" type Pay interface { Pay(string) int } type PayReq struct { OrderId string } type APayReq struct { PayReq } func (p *APayReq) Pay() string { // todo fmt.Println(p.OrderId) return "APay支付成功" } type BPayReq struct { PayReq Uid int64 } func (p *BPayReq) Pay() string { // todo fmt.Println(p.OrderId) fmt.Println(p.Uid) return "BPay支付成功" } |

我们用APay和BPay两个结构体重写了Pay() 方法,如果需要添加一种新的支付方式, 只需要重写新的Pay() 方法即可。

工厂方法的优点就在于避免了创建者和具体产品之间的紧密耦合,从而使得代码更容易维护。

测试代码:

| 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 |

package factorymethod import ( "testing" ) func TestPay(t *testing.T) { aPay := APayReq{} if aPay.Pay() != "APay支付成功" { t.Fatal("aPay error") } bPay := BPayReq{} if bPay.Pay() != "BPay支付成功" { t.Fatal("bPay error") } } |

抽象工厂模式 Abstract Factory

问题

抽象工厂模式基于工厂方法模式。两者的区别在于:工厂方法模式是创建出一种产品,而抽象工厂模式是创建出一类产品。这二种都属于工厂模式,在设计上是相似的。

假设,有一个存储工厂,提供redis和mysql两种存储数据的方式。如果使用工厂方法模式,我们就需要一个存储工厂,并提供SaveRedis方法和SaveMysql方法。

如果此时业务还需要分成存储散文和古诗两种载体,这两种载体都可以进行redis和mysql存储。就可以使用抽象工厂模式,我们需要一个存储工厂作为父工厂,散文工厂和古诗工厂作为子工厂,并提供SaveRedis方法和SaveMysql方法。

解决

以上文的存储工厂业务为例,用抽象工厂模式的思路来设计代码,就像下面这样:

| 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 |

package abstractfactory import "fmt" // SaveArticle 抽象模式工厂接口 type SaveArticle interface { CreateProse() Prose CreateAncientPoetry() AncientPoetry } type SaveRedis struct{} func (*SaveRedis) CreateProse() Prose { return &RedisProse{} } func (*SaveRedis) CreateAncientPoetry() AncientPoetry { return &RedisProse{} } type SaveMysql struct{} func (*SaveMysql) CreateProse() Prose { return &MysqlProse{} } func (*SaveMysql) CreateAncientPoetry() AncientPoetry { return &MysqlProse{} } // Prose 散文 type Prose interface { SaveProse() } // AncientPoetry 古诗 type AncientPoetry interface { SaveAncientPoetry() } type RedisProse struct{} func (*RedisProse) SaveProse() { fmt.Println("Redis Save Prose") } func (*RedisProse) SaveAncientPoetry() { fmt.Println("Redis Save Ancient Poetry") } type MysqlProse struct{} func (*MysqlProse) SaveProse() { fmt.Println("Mysql Save Prose") } func (*MysqlProse) SaveAncientPoetry() { fmt.Println("Mysql Save Ancient Poetry") } |

我们定义了存储工厂,也就是SaveArticle接口,并实现了CreateProse方法和CreateAncientPoetry方法,这2个方法分别用于创建散文工厂和古诗工厂。

然后我们又分别为散文工厂和古诗工厂实现了SaveProse方法和SaveAncientPoetry方法,并用Redis结构体和Mysql结构体分别重写了2种存储方法。

测试代码:

| 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 |

package abstractfactory func Save(saveArticle SaveArticle) { saveArticle.CreateProse().SaveProse() saveArticle.CreateAncientPoetry().SaveAncientPoetry() } func ExampleSaveRedis() { var factory SaveArticle factory = &SaveRedis{} Save(factory) // Output: // Redis Save Prose // Redis Save Ancient Poetry } func ExampleSaveMysql() { var factory SaveArticle factory = &SaveMysql{} Save(factory) // Output: // Mysql Save Prose // Mysql Save Ancient Poetry } |

建造者模式 Builder

问题

假设业务需要按步骤创建一系列复杂的对象,实现这些步骤的代码加在一起非常繁复,我们可以将这些代码放进一个包含了众多参数的构造函数中,但这个构造函数看起来将会非常杂乱无章,且难以维护。

假设业务需要建造一个房子对象,需要先打地基、建墙、建屋顶、建花园、放置家具……。我们需要非常多的步骤,并且这些步骤之间是有联系的,即使将各个步骤从一个大的构造函数抽出到其他小函数中,整个程序的层次结构看起来依然很复杂。

如何解决呢?像这种复杂的有许多步骤的构造函数,就可以用建造者模式来设计。

建造者模式的用处就在于能够分步骤创建复杂对象。

解决

在建造者模式中,我们需要清晰的定义每个步骤的代码,然后在一个构造函数中操作这些步骤,我们需要一个主管类,用这个主管类来管理各步骤。这样我们就只需要将所需参数传给一个构造函数,构造函数再将参数传递给对应的主管类,最后由主管类完成后续所有建造任务。

请看以下代码:

| 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 |

package builder import "fmt" // 建造者接口 type Builder interface { Part1() Part2() Part3() } // 管理类 type Director struct { builder Builder } // 构造函数 func NewDirector(builder Builder) *Director { return &Director{ builder: builder, } } // 建造 func (d *Director) Construct() { d.builder.Part1() d.builder.Part2() d.builder.Part3() } type Builder struct {} func (b *Builder) Part1() { fmt.Println("part1") } func (b *Builder) Part2() { fmt.Println("part2") } func (b *Builder) Part3() { fmt.Println("part3") } |

如上,我们实现part1、part2、part3这3个步骤,只需要执行构造函数,对应的管理类就可以运行建造方法Construct,完成3个步骤的执行。

测试代码:

| 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 |

package builder func ExampleBuilder() { builder := &Builder{} director := NewDirector(builder) director.Construct() // Output: // part1 // part2 // part3 } |

原型模式 Prototype

问题

如果你希望生成一个对象,其与另一个对象完全相同,该如何实现呢?

如果遍历对象的所有成员,将其依次复制到新对象中,会稍显麻烦,而且有些对象可能会有私有成员变量遗漏。

原型模式将这个克隆的过程委派给了被克隆的实际对象,被克隆的对象就叫做“原型”。

解决

如果需要克隆一个新的对象,这个对象完全独立于它的原型,那么就可以使用原型模式。

原型模式的实现非常简单,请看以下代码:

| 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 |

package prototype import "testing" var manager *PrototypeManager type Type1 struct { name string } func (t *Type1) Clone() *Type1 { tc := *t return &tc } func TestClone(t *testing.T) { t1 := &Type1{ name: "type1", } t2 := t1.Clone() if t1 == t2 { t.Fatal("error! get clone not working") } } |

我们依靠一个Clone方法实现了原型Type1的克隆。

原型模式的用处就在于我们可以克隆对象,而无需与原型对象的依赖相耦合。

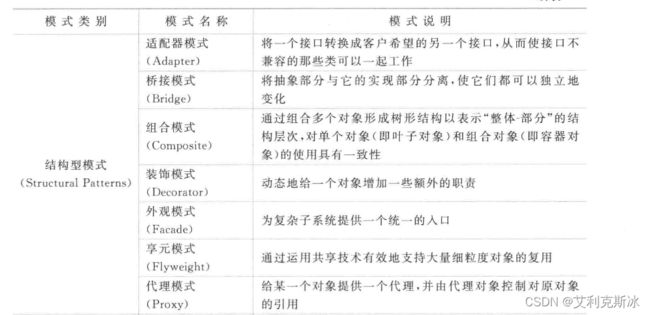

结构型模式

结构型模式将一些对象和类组装成更大的结构体,并同时保持结构的灵活和高效。

适配器模式 Adapter

问题

适配器模式说白了就是兼容。

假设一开始我们提供了A对象,后期随着业务迭代,又需要从A对象的基础之上衍生出不同的需求。如果有很多函数已经在线上调用了A对象,此时再对A对象进行修改就比较麻烦,因为需要考虑兼容问题。还有更糟糕的情况, 你可能没有程序库的源代码, 从而无法对其进行修改。

此时就可以用一个适配器,它就像一个接口转换器,调用方只需要调用这个适配器接口,而不需要关注其背后的实现,由适配器接口封装复杂的过程。

解决

假设有2个接口,一个将厘米转为米,一个将米转为厘米。我们提供一个适配器接口,使调用方不需要再操心调用哪个接口,直接由适配器做好兼容。

请看以下代码:

| 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 |

package adapter // 提供一个获取米的接口和一个获取厘米的接口 type Cm interface { getLength(float64) float64 } type M interface { getLength(float64) float64 } func NewM() M { return &getLengthM{} } type getLengthM struct{} func (*getLengthM) getLength(cm float64) float64 { return cm / 10 } func NewCm() Cm { return &getLengthCm{} } type getLengthCm struct{} func (a *getLengthCm) getLength(m float64) float64 { return m * 10 } // 适配器 type LengthAdapter interface { getLength(string, float64) float64 } func NewLengthAdapter() LengthAdapter { return &getLengthAdapter{} } type getLengthAdapter struct{} func (*getLengthAdapter) getLength(isType string, into float64) float64 { if isType == "m" { return NewM().getLength(into) } return NewCm().getLength(into) } |

上面实现了Cm和M两个接口,并由适配器LengthAdapter做兼容。

测试代码:

| 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 |

package adapter import "testing" func TestAdapter(t *testing.T) { into := 10.5 getLengthAdapter := NewLengthAdapter().getLength("m", into) getLengthM := NewM().getLength(into) if getLengthAdapter != getLengthM { t.Fatalf("getLengthAdapter: %f, getLengthM: %f", getLengthAdapter, getLengthM) } } |

桥接模式Bridge

问题

假设一开始业务需要两种发送信息的渠道,sms和email,我们可以分别实现sms和email两个接口。

之后随着业务迭代,又产生了新的需求,需要提供两种系统发送方式,systemA和systemB,并且这两种系统发送方式都应该支持sms和email渠道。

此时至少需要提供4种方法:systemA to sms,systemA to email,systemB to sms,systemB to email。

如果再分别增加一种渠道和一种系统发送方式,就需要提供9种方法。这将导致代码的复杂程度指数增长。

解决

其实之前我们是在用继承的想法来看问题,桥接模式则希望将继承关系转变为关联关系,使两个类独立存在。

详细说一下:

- 桥接模式需要将抽象和实现区分开;

- 桥接模式需要将“渠道”和“系统发送方式”这两种类别区分开;

- 最后在“系统发送方式”的类里调用“渠道”的抽象接口,使他们从继承关系转变为关联关系。

用一句话总结桥接模式的理念,就是:“将抽象与实现解耦,将不同类别的继承关系改为关联关系。 ”

请看以下代码:

| 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 |

package bridge import "fmt" // 两种发送消息的方法 type SendMessage interface { send(text, to string) } type sms struct{} func NewSms() SendMessage { return &sms{} } func (*sms) send(text, to string) { fmt.Println(fmt.Sprintf("send %s to %s sms", text, to)) } type email struct{} func NewEmail() SendMessage { return &email{} } func (*email) send(text, to string) { fmt.Println(fmt.Sprintf("send %s to %s email", text, to)) } // 两种发送系统 type systemA struct { method SendMessage } func NewSystemA(method SendMessage) *systemA { return &systemA{ method: method, } } func (m *systemA) SendMessage(text, to string) { m.method.send(fmt.Sprintf("[System A] %s", text), to) } type systemB struct { method SendMessage } func NewSystemB(method SendMessage) *systemB { return &systemB{ method: method, } } func (m *systemB) SendMessage(text, to string) { m.method.send(fmt.Sprintf("[System B] %s", text), to) } |

可以看到我们先定义了sms和email二种实现,以及接口SendMessage。接着我们实现了systemA和systemB,并调用了抽象接口SendMessage。

测试代码:

| 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 |

package bridge func ExampleSystemA() { NewSystemA(NewSms()).SendMessage("hi", "baby") NewSystemA(NewEmail()).SendMessage("hi", "baby") // Output: // send [System A] hi to baby sms // send [System A] hi to baby email } func ExampleSystemB() { NewSystemB(NewSms()).SendMessage("hi", "baby") NewSystemB(NewEmail()).SendMessage("hi", "baby") // Output: // send [System B] hi to baby sms // send [System B] hi to baby email } |

如果你想要拆分或重组一个具有多重功能的复杂类,可以使用桥接模式。

对象树模式Object Tree

问题

在项目中,如果我们需要用到树状结构,就可以使用对象树模式。换言之,如果项目的核心模型不能以树状结构表示,则没必要使用对象树模式。

对象树模式的用处就在于可以利用多态和递归机制更方便地使用复杂树结构。

解决

请看以下代码:

| 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 |

package objecttree import "fmt" type Component interface { Parent() Component SetParent(Component) Name() string SetName(string) AddChild(Component) Search(string) } const ( LeafNode = iota CompositeNode ) func NewComponent(kind int, name string) Component { var c Component switch kind { case LeafNode: c = NewLeaf() case CompositeNode: c = NewComposite() } c.SetName(name) return c } type component struct { parent Component name string } func (c *component) Parent() Component { return c.parent } func (c *component) SetParent(parent Component) { c.parent = parent } func (c *component) Name() string { return c.name } func (c *component) SetName(name string) { c.name = name } func (c *component) AddChild(Component) {} type Leaf struct { component } func NewLeaf() *Leaf { return &Leaf{} } func (c *Leaf) Search(pre string) { fmt.Printf("leaf %s-%s\n", pre, c.Name()) } type Composite struct { component childs []Component } func NewComposite() *Composite { return &Composite{ childs: make([]Component, 0), } } func (c *Composite) AddChild(child Component) { child.SetParent(c) c.childs = append(c.childs, child) } func (c *Composite) Search(pre string) { fmt.Printf("%s+%s\n", pre, c.Name()) pre += " " for _, comp := range c.childs { comp.Search(pre) } } |

在Search方法中使用递归打印出了整棵树结构。

测试代码:

| 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 |

package objecttree func ExampleComposite() { root := NewComponent(CompositeNode, "root") c1 := NewComponent(CompositeNode, "c1") c2 := NewComponent(CompositeNode, "c2") c3 := NewComponent(CompositeNode, "c3") l1 := NewComponent(LeafNode, "l1") l2 := NewComponent(LeafNode, "l2") l3 := NewComponent(LeafNode, "l3") root.AddChild(c1) root.AddChild(c2) c1.AddChild(c3) c1.AddChild(l1) c2.AddChild(l2) c2.AddChild(l3) root.Search("") // Output: // +root // +c1 // +c3 //leaf -l1 // +c2 //leaf -l2 //leaf -l3 } |

装饰模式Decorator

问题

有时候我们需要在一个类的基础上扩展另一个类,例如,一个披萨类,你可以在披萨类的基础上增加番茄披萨类和芝士披萨类。此时就可以使用装饰模式,简单来说,装饰模式就是将对象封装到另一个对象中,用以为原对象绑定新的行为。

如果你希望在无需修改代码的情况下使用对象,并且希望为对象新增额外的行为,就可以考虑使用装饰模式。

解决

用上文的披萨类做例子。请看以下代码:

| 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 |

package decorator type pizza interface { getPrice() int } type base struct {} func (p *base) getPrice() int { return 15 } type tomatoTopping struct { pizza pizza } func (c *tomatoTopping) getPrice() int { pizzaPrice := c.pizza.getPrice() return pizzaPrice + 10 } type cheeseTopping struct { pizza pizza } func (c *cheeseTopping) getPrice() int { pizzaPrice := c.pizza.getPrice() return pizzaPrice + 20 } |

首先我们定义了pizza接口,创建了base类,实现了方法getPrice。然后再用装饰模式的理念,实现了tomatoTopping和cheeseTopping类,他们都封装了pizza接口的getPrice方法。

测试代码:

| 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 |

package decorator import "fmt" func ExampleDecorator() { pizza := &base{} //Add cheese topping pizzaWithCheese := &cheeseTopping{ pizza: pizza, } //Add tomato topping pizzaWithCheeseAndTomato := &tomatoTopping{ pizza: pizzaWithCheese, } fmt.Printf("price is %d\n", pizzaWithCheeseAndTomato.getPrice()) // Output: // price is 45 } |

外观模式Facade

问题

如果你需要初始化大量复杂的库或框架,就需要管理其依赖关系并且按正确的顺序执行。此时就可以用一个外观类来统一处理这些依赖关系,以对其进行整合。

解决

外观模式和建造者模式很相似。两者的区别在于,外观模式是一种结构型模式,她的目的是将对象组合起来,而不是像建造者模式那样创建出不同的产品。

请看以下代码:

| 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 |

package facade import "fmt" // 初始化APIA和APIB type APIA interface { TestA() string } func NewAPIA() APIA { return &apiRunA{} } type apiRunA struct{} func (*apiRunA) TestA() string { return "A api running" } type APIB interface { TestB() string } func NewAPIB() APIB { return &apiRunB{} } type apiRunB struct{} func (*apiRunB) TestB() string { return "B api running" } // 外观类 type API interface { Test() string } func NewAPI() API { return &apiRun{ a: NewAPIA(), b: NewAPIB(), } } type apiRun struct { a APIA b APIB } func (a *apiRun) Test() string { aRet := a.a.TestA() bRet := a.b.TestB() return fmt.Sprintf("%s\n%s", aRet, bRet) } |

假设要初始化APIA和APIB,我们就可以通过一个外观类API进行处理,在外观类接口Test方法中分别执行类TestA方法和TestB方法。

测试代码:

| 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 |

package facade import "testing" var expect = "A api running\nB api running" // TestFacadeAPI ... func TestFacadeAPI(t *testing.T) { api := NewAPI() ret := api.Test() if ret != expect { t.Fatalf("expect %s, return %s", expect, ret) } } |

享元模式 Flyweight

问题

在一些情况下,程序没有足够的内存容量支持存储大量对象,或者大量的对象存储着重复的状态,此时就会造成内存资源的浪费。

享元模式提出了这样的解决方案:如果多个对象中相同的状态可以共用,就能在在有限的内存容量中载入更多对象。

解决

如上所说,享元模式希望抽取出能在多个对象间共享的重复状态。

我们可以使用map结构来实现这一设想,假设需要存储一些代表颜色的对象,使用享元模式可以这样做,请看以下代码:

| 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 |

package flyweight import "fmt" // 享元工厂 type ColorFlyweightFactory struct { maps map[string]*ColorFlyweight } var colorFactory *ColorFlyweightFactory func GetColorFlyweightFactory() *ColorFlyweightFactory { if colorFactory == nil { colorFactory = &ColorFlyweightFactory{ maps: make(map[string]*ColorFlyweight), } } return colorFactory } func (f *ColorFlyweightFactory) Get(filename string) *ColorFlyweight { color := f.maps[filename] if color == nil { color = NewColorFlyweight(filename) f.maps[filename] = color } return color } type ColorFlyweight struct { data string } // 存储color对象 func NewColorFlyweight(filename string) *ColorFlyweight { // Load color file data := fmt.Sprintf("color data %s", filename) return &ColorFlyweight{ data: data, } } type ColorViewer struct { *ColorFlyweight } func NewColorViewer(name string) *ColorViewer { color := GetColorFlyweightFactory().Get(name) return &ColorViewer{ ColorFlyweight: color, } } |

我们定义了一个享元工厂,使用map存储相同对象(key)的状态(value)。这个享元工厂可以使我们更方便和安全的访问各种享元,保证其状态不被修改。

我们定义了NewColorViewer方法,它会调用享元工厂的Get方法存储对象,而在享元工厂的实现中可以看到,相同状态的对象只会占用一次。

测试代码:

| 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 |

package flyweight import "testing" func TestFlyweight(t *testing.T) { viewer1 := NewColorViewer("blue") viewer2 := NewColorViewer("blue") if viewer1.ColorFlyweight != viewer2.ColorFlyweight { t.Fail() } } |

当程序需要存储大量对象且没有足够的内存容量时,可以考虑使用享元模式。

代理模式Proxy

问题

如果你需要在访问一个对象时,有一个像“代理”一样的角色,她可以在访问对象之前为你进行缓存检查、权限判断等访问控制,在访问对象之后为你进行结果缓存、日志记录等结果处理,那么就可以考虑使用代理模式。

回忆一下一些web框架的router模块,当客户端访问一个接口时,在最终执行对应的接口之前,router模块会执行一些事前操作,进行权限判断等操作,在执行之后还会记录日志,这就是典型的代理模式。

解决

代理模式需要一个代理类,其包含执行真实对象所需的成员变量,并由代理类管理整个生命周期。

请看以下代码:

| 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 |

package proxy import "fmt" type Subject interface { Proxy() string } // 代理 type Proxy struct { real RealSubject } func (p Proxy) Proxy() string { var res string // 在调用真实对象之前,检查缓存,判断权限,等等 p.real.Pre() // 调用真实对象 p.real.Real() // 调用之后的操作,如缓存结果,对结果进行处理,等等 p.real.After() return res } // 真实对象 type RealSubject struct{} func (RealSubject) Real() { fmt.Print("real") } func (RealSubject) Pre() { fmt.Print("pre:") } func (RealSubject) After() { fmt.Print(":after") } |

我们定义了代理类Proxy,执行Proxy之后,在调用真实对象Real之前,我们会先调用事前对象Pre,并在执行真实对象Real之后,调用事后对象After。

测试代码:

| 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 |

package proxy func ExampleProxy() { var sub Subject sub = &Proxy{} sub.Proxy() // Output: // pre:real:after } |

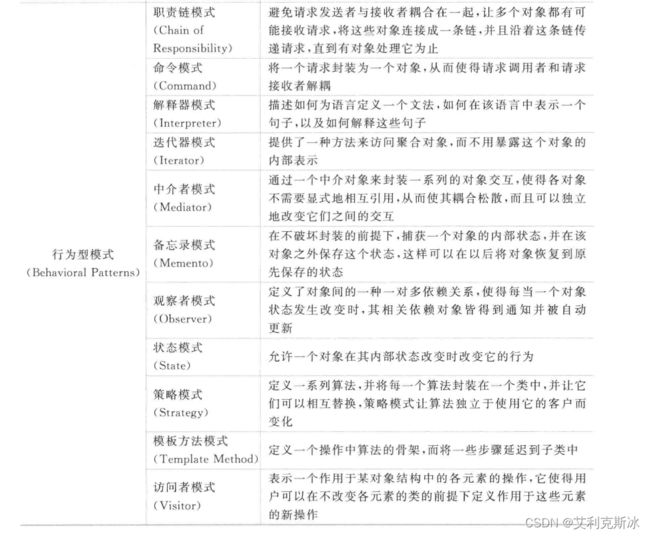

行为型模式

行为型模式处理对象和类之间的通信,并使其保持高效的沟通和委派。

责任链模式Chain of Responsibility

问题

假设我们要让程序按照指定的步骤执行,并且这个步骤的顺序不是固定的,而是可以根据不同需求改变的,每个步骤都会对请求进行一些处理,并将结果传递给下一个步骤的处理者,就像一条流水线一样,我们该如何实现?

当遇到这种必须按顺序执行多个处理者,并且处理者的顺序可以改变的需求,我们可以考虑使用责任链模式。

解决

责任链模式使用了类似链表的结构。请看以下代码:

| 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 |

package chain import "fmt" type department interface { execute(*Do) setNext(department) } type aPart struct { next department } func (r *aPart) execute(p *Do) { if p.aPartDone { fmt.Println("aPart done") r.next.execute(p) return } fmt.Println("aPart") p.aPartDone = true r.next.execute(p) } func (r *aPart) setNext(next department) { r.next = next } type bPart struct { next department } func (d *bPart) execute(p *Do) { if p.bPartDone { fmt.Println("bPart done") d.next.execute(p) return } fmt.Println("bPart") p.bPartDone = true d.next.execute(p) } func (d *bPart) setNext(next department) { d.next = next } type endPart struct { next department } func (c *endPart) execute(p *Do) { if p.endPartDone { fmt.Println("endPart Done") } fmt.Println("endPart") } func (c *endPart) setNext(next department) { c.next = next } type Do struct { aPartDone bool bPartDone bool endPartDone bool } |

我们实现了方法execute和setNext,并定义了aPart、bPart、endPart这3个处理者,每个处理者都可以通过execute方法执行其对应的业务代码,并可以通过setNext方法决定下一个处理者是谁。除了endPart是最终的处理者之外,在它之前的处理者aPart、bPart的顺序都可以任意调整。

请看以下测试代码:

| 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 |

func ExampleChain() { startPart := &endPart{} aPart := &aPart{} aPart.setNext(startPart) bPart := &bPart{} bPart.setNext(aPart) do := &Do{} bPart.execute(do) // Output: // bPart // aPart // endPart } |

我们也可以调整处理者的执行顺序:

| 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 |

func ExampleChain2() { startPart := &endPart{} bPart := &bPart{} bPart.setNext(startPart) aPart := &aPart{} aPart.setNext(bPart) do := &Do{} aPart.execute(do) // Output: // aPart // bPart // endPart } |

命令模式Command

问题

假设你实现了开启和关闭电视机的功能,随着业务迭代,还需要实现开启和关闭冰箱的功能,开启和关闭电灯的功能,开启和关闭微波炉的功能……这些功能都基于你的基类,开启和关闭。如果你之后对基类进行修改,很可能会影响到其他功能,这使项目变得不稳定了。

一个优秀的设计往往会关注于软件的分层与解耦,命令模式试图做到这样的结果:让命令和对应功能解耦,并能根据不同的请求将其方法参数化。

解决

还是用开启和关闭家用电器的例子来举例吧。请看以下代码:

| 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 |

package command import "fmt" // 请求者 type button struct { command command } func (b *button) press() { b.command.execute() } // 具体命令接口 type command interface { execute() } type onCommand struct { device device } func (c *onCommand) execute() { c.device.on() } type offCommand struct { device device } func (c *offCommand) execute() { c.device.off() } // 接收者 type device interface { on() off() } type tv struct{} func (t *tv) on() { fmt.Println("Turning tv on") } func (t *tv) off() { fmt.Println("Turning tv off") } type airConditioner struct{} func (t *airConditioner) on() { fmt.Println("Turning air conditioner on") } func (t *airConditioner) off() { fmt.Println("Turning air conditioner off") } |

我们分别实现了请求者button,命令接口command,接收者device。请求者button就像是那个可以执行开启或关闭的遥控器,命令接口command则是一个中间层,它使我们的请求者和接收者解藕。

测试代码:

| 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 |

package command func ExampleCommand() { Tv() AirConditioner() // Output: // Turning tv on // Turning tv off // Turning air conditioner on // Turning air conditioner off } func Tv() { tv := &tv{} onTvCommand := &onCommand{ device: tv, } offTvCommand := &offCommand{ device: tv, } onTvButton := &button{ command: onTvCommand, } onTvButton.press() offTvButton := &button{ command: offTvCommand, } offTvButton.press() } func AirConditioner() { airConditioner := &airConditioner{} onAirConditionerCommand := &onCommand{ device: airConditioner, } offAirConditionerCommand := &offCommand{ device: airConditioner, } onAirConditionerButton := &button{ command: onAirConditionerCommand, } onAirConditionerButton.press() offAirConditionerButton := &button{ command: offAirConditionerCommand, } offAirConditionerButton.press() } |

迭代器模式Iterator

问题

迭代器模式用于遍历集合中的元素,无论集合的数据结构是怎样的。

解决

请看以下代码:

| 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 |

package iterator // 集合接口 type collection interface { createIterator() iterator } // 具体的集合 type part struct { title string number int } type partCollection struct { part parts []*part } func (u *partCollection) createIterator() iterator { return &partIterator{ parts: u.parts, } } // 迭代器 type iterator interface { hasNext() bool getNext() *part } // 具体的迭代器 type partIterator struct { index int parts []*part } func (u *partIterator) hasNext() bool { if u.index < len(u.parts) { return true } return false } func (u *partIterator) getNext() *part { if u.hasNext() { part := u.parts[u.index] u.index++ return part } return nil } |

测试代码:

| 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 |

func ExampleIterator() { part1 := &part{ title: "part1", number: 10, } part2 := &part{ title: "part2", number: 20, } part3 := &part{ title: "part3", number: 30, } partCollection := &partCollection{ parts: []*part{part1, part2, part3}, } iterator := partCollection.createIterator() for iterator.hasNext() { part := iterator.getNext() fmt.Println(part) } // Output: // &{part1 10} // &{part2 20} // &{part3 30} } |

中介者模式Mediator

问题

中介者模式试图解决网状关系的复杂关联,降低对象间的耦合度。

举个例子,假设一个十字路口上的车都是对象,它们会执行不同的操作,前往不同的目的地,那么在十字路口指挥的交警就是“中介者”。

各个对象通过执行中介者接口,再由中介者维护对象之间的联系。这能使对象变得更独立,比较适合用在一些对象是网状关系的案例上。

解决

假设有p1,p2,p3这3个发送者,p1 发送的消息p2能收到,p2 发送的消息p1能收到,p3 发送的消息则p1和p2能收到,如何实现呢?像这种情况就很适合用中介者模式实现。

请看以下代码:

| 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 |

package mediator import ( "fmt" ) type p1 struct{} func (p *p1) getMessage(data string) { fmt.Println("p1 get message: " + data) } type p2 struct{} func (p *p2) getMessage(data string) { fmt.Println("p2 get message: " + data) } type p3 struct{} func (p *p3) getMessage(data string) { fmt.Println("p3 get message: " + data) } type Message struct { p1 *p1 p2 *p2 p3 *p3 } func (m *Message) sendMessage(i interface{}, data string) { switch i.(type) { case *p1: m.p2.getMessage(data) case *p2: m.p1.getMessage(data) case *p3: m.p1.getMessage(data) m.p2.getMessage(data) } } |

我们定义了p1,p2,p3这3个对象,然后实现了中介者sendMessage。

测试代码:

| 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 |

package mediator func ExampleMediator() { message := &Message{} p1 := &p1{} p2 := &p2{} p3 := &p3{} message.sendMessage(p1, "hi! my name is p1") message.sendMessage(p2, "hi! my name is p2") message.sendMessage(p3, "hi! my name is p3") // Output: // p2 get message: hi! my name is p1 // p1 get message: hi! my name is p2 // p1 get message: hi! my name is p3 // p2 get message: hi! my name is p3 } |

备忘录模式Memento

问题

常用的文字编辑器都支持保存和恢复一段文字的操作,如果我们想要在程序中实现保存和恢复的功能该怎么做呢?

我们需要提供保存和恢复的功能,当保存功能被调用时,就会生成当前对象的快照,在恢复功能被调用时,就会用之前保存的快照覆盖当前的快照。这可以使用备忘录模式来做。

解决

请看以下代码:

| 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 |

package memento import "fmt" type Memento interface{} type Text struct { content string } type textMemento struct { content string } func (t *Text) Write(content string) { t.content = content } func (t *Text) Save() Memento { return &textMemento{ content: t.content, } } func (t *Text) Load(m Memento) { tm := m.(*textMemento) t.content = tm.content } func (t *Text) Show() { fmt.Println("content:", t.content) } |

我们定义了textMemento结构体用于保存当前快照,并在Load方法中将快照覆盖到当前内容。

测试代码:

| 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 |

package memento func ExampleText() { text := &Text{ content: "how are you", } text.Show() progress := text.Save() text.Write("fine think you and you") text.Show() text.Load(progress) text.Show() // Output: // content: how are you // content: fine think you and you // content: how are you } |

观察者模式Observer

问题

如果你需要在一个对象的状态被改变时,其他对象能作为其“观察者”而被通知,就可以使用观察者模式。

我们将自身的状态改变就会通知给其他对象的对象称为“发布者”,关注发布者状态变化的对象则称为“订阅者”。

解决

请看以下代码:

| 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 |

package observer import "fmt" // 发布者 type Subject struct { observers []Observer content string } func NewSubject() *Subject { return &Subject{ observers: make([]Observer, 0), } } // 添加订阅者 func (s *Subject) AddObserver(o Observer) { s.observers = append(s.observers, o) } // 改变发布者的状态 func (s *Subject) UpdateContext(content string) { s.content = content s.notify() } // 通知订阅者接口 type Observer interface { Do(*Subject) } func (s *Subject) notify() { for _, o := range s.observers { o.Do(s) } } // 订阅者 type Reader struct { name string } func NewReader(name string) *Reader { return &Reader{ name: name, } } func (r *Reader) Do(s *Subject) { fmt.Println(r.name + " get " + s.content) } |

很简单,我们只要实现一个通知notify方法,在发布者的状态改变时执行即可。

测试代码:

| 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 |

package observer func ExampleObserver() { subject := NewSubject() boy := NewReader("小明") girl := NewReader("小美") subject.AddObserver(boy) subject.AddObserver(girl) subject.UpdateContext("hi~") // Output: // 小明 get hi~ // 小美 get hi~ } |

状态模式 State

问题

如果一个对象的实现方法会根据自身的状态而改变,就可以使用状态模式。

举个例子:假设有一个开门的方法,门的状态在一开始是“关闭”,你可以执行open方法和close方法,当你执行了open方法,门的状态就变成了“开启”,再执行open方法就不会执行开门的功能,而是返回“门已开启”,如果执行close方法,门的状态就变成了“关闭”,再执行close方法就不会执行关门的功能,而是返回“门已关闭”。这是一个简单的例子,我们将为每个状态提供不同的实现方法,将这些方法组织起来很麻烦,如果状态也越来越多呢?无疑,这将会使代码变得臃肿。

解决

如果我们需要为一个门对象提供3种状态下的open和close方法:

- “开启”状态下,open方法返回“门已开启”,close方法返回“关闭成功”。

- “关闭”状态下,open方法返回“开启成功”,close方法返回“门已关闭”。

- “损坏”状态下,open方法返回“门已损坏,无法开启”,close方法返回“门已损坏,无法关闭”。

请看以下代码:

| 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 |

package state import "fmt" // 不同状态需要实现的接口 type state interface { open(*door) close(*door) } // 门对象 type door struct { opened state closed state damaged state currentState state // 当前状态 } func (d *door) open() { d.currentState.open(d) } func (d *door) close() { d.currentState.close(d) } func (d *door) setState(s state) { d.currentState = s } // 开启状态 type opened struct{} func (o *opened) open(d *door) { fmt.Println("门已开启") } func (o *opened) close(d *door) { fmt.Println("关闭成功") } // 关闭状态 type closed struct{} func (c *closed) open(d *door) { fmt.Println("开启成功") } func (c *closed) close(d *door) { fmt.Println("门已关闭") } // 损坏状态 type damaged struct{} func (a *damaged) open(d *door) { fmt.Println("门已损坏,无法开启") } func (a *damaged) close(d *door) { fmt.Println("门已损坏,无法关闭") } |

我们的门对象door实现了open和close方法,在方法中,只需要调用当前状态currentState的open和close方法即可。

测试代码:

| 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 |

package state func ExampleState() { door := &door{} // 开启状态 opened := &opened{} door.setState(opened) door.open() door.close() // 关闭状态 closed := &closed{} door.setState(closed) door.open() door.close() // 损坏状态 damaged := &damaged{} door.setState(damaged) door.open() door.close() // Output: // 门已开启 // 关闭成功 // 开启成功 // 门已关闭 // 门已损坏,无法开启 // 门已损坏,无法关闭 } |

策略模式Strategy

问题

假设需要实现一组出行的功能,出现的方案可以选择步行、骑行、开车,最简单的做法就是分别实现这3种方法供客户端调用。但这样做就使对象与其代码实现变得耦合了,客户端需要决定出行方式,然后决定调用步行出行、骑行出行、开车出行等方法,这不符合开闭原则。

而策略模式的区别在于,它会将这些出行方案抽取到一组被称为策略的类中,客户端还是调用同一个出行对象,不需要关注实现细节,只需要在参数中指定所需的策略即可。

解决

请看以下代码:

| 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 |

package strategy import "fmt" type Travel struct { name string strategy Strategy } func NewTravel(name string, strategy Strategy) *Travel { return &Travel{ name: name, strategy: strategy, } } func (p *Travel) traffic() { p.strategy.traffic(p) } type Strategy interface { traffic(*Travel) } type Walk struct{} func (w *Walk) traffic(t *Travel) { fmt.Println(t.name + " walk") } type Ride struct{} func (w *Ride) traffic(t *Travel) { fmt.Println(t.name + " ride") } type Drive struct{} func (w *Drive) traffic(t *Travel) { fmt.Println(t.name + " drive") } |

我们定义了strategy一组策略接口,为其实现了Walk、Ride、Drive算法。客户端只需要执行traffic方法即可,无需关注实现细节。

测试代码:

| 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 |

package strategy func ExampleTravel() { walk := &Walk{} Travel1 := NewTravel("小明", walk) Travel1.traffic() ride := &Ride{} Travel2 := NewTravel("小美", ride) Travel2.traffic() drive := &Drive{} Travel3 := NewTravel("小刚", drive) Travel3.traffic() // Output: // 小明 walk // 小美 ride // 小刚 drive } |

模板方法模式Template Method

问题

模板方法模式就是将算法分解为一系列步骤,然后在一个模版方法中依次调用这些步骤。这样客户端就不需要了解各个步骤的实现细节,只需要调用模版即可。

解决

一个非常简单的例子,请看以下代码:

| 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 |

package templatemethod import "fmt" type PrintTemplate interface { Print(name string) } type template struct { isTemplate PrintTemplate name string } func (t *template) Print() { t.isTemplate.Print(t.name) } type A struct{} func (a *A) Print(name string) { fmt.Println("a: " + name) // 业务代码…… } type B struct{} func (b *B) Print(name string) { fmt.Println("b: " + name) // 业务代码…… } |

测试代码:

| 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 |

package templatemethod func ExamplePrintTemplate() { templateA := &A{} template := &template{ isTemplate: templateA, name: "hi~", } template.Print() templateB := &B{} template.isTemplate = templateB template.Print() // Output: // a: hi~ // b: hi~ } |

访问者模式Visitor

问题

访问者模式试图解决这样一个问题:在不改变类的对象结构的前提下增加新的操作。

解决

请看以下代码:

| 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 |

package visitor import "fmt" type Shape interface { accept(visitor) } type square struct{} func (s *square) accept(v visitor) { v.visitForSquare(s) } type circle struct{} func (c *circle) accept(v visitor) { v.visitForCircle(c) } type visitor interface { visitForSquare(*square) visitForCircle(*circle) } type sideCalculator struct{} func (a *sideCalculator) visitForSquare(s *square) { fmt.Println("square side") } func (a *sideCalculator) visitForCircle(s *circle) { fmt.Println("circle side") } type radiusCalculator struct{} func (a *radiusCalculator) visitForSquare(s *square) { fmt.Println("square radius") } func (a *radiusCalculator) visitForCircle(c *circle) { fmt.Println("circle radius") } |

测试代码:

| 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 |

package visitor func ExampleShape() { square := &square{} circle := &circle{} side := &sideCalculator{} square.accept(side) circle.accept(side) radius := &radiusCalculator{} square.accept(radius) circle.accept(radius) // Output: // square side // circle side // square radius // circle radius } |