Java EE meets Web 2.0

http://www.ibm.com/developerworks/web/library/wa-aj-web2jee/?S_CMP=cn-a-wa&S_TACT=105AGX52

Summary: Web 2.0 applications developed using standard Java™ Platform, Enterprise Edition 5 (Java EE)-based approaches face serious performance and scalability problems. The reason is that many principles that underlie the Java EE platform's design — especially, the use of synchronous APIs — don't apply to the requirements of Web 2.0 solutions. This article explains the disparity between the Java EE and Web 2.0 approaches, explores the benefits of asynchronous designs, and evaluates some solutions for developing asynchronous Web applications with the Java platform.

Tags for this article: asynchronous , concurrency , j2ee , java , latency , performance , seda , web , web20

Date: 06 Nov 2007

Level: Intermediate

Also available in: Chinese Korean Russian Japanese

Activity: 18966 views

Comments: 0 (Add comments )

A tremendous number of successful enterprise applications have been created using the Java EE platform. But the principles Java EE was designed on don't support the Web 2.0 generation of applications efficiently. An in-depth understanding of the disconnect between Java EE and Web 2.0 principles can help you make informed decisions about using approaches and tools that address that disconnect to some degree. This article explains why Web 2.0 and the standard Java EE platform are a losing combination, and it demonstrates why asynchronous, event-driven architectures are more appropriate for Web 2.0 applications. It also describes frameworks and APIs that aim to make the Java platform more Web 2.0 capable by enabling asynchronous designs.

Java EE principles and assumptions

The Java EE platform was created to support development of business-to-consumer (B2C) and business-to-business (B2B) applications. Companies discovered the Internet and started using it to enhance existing business processes with their partners and clients. These applications often interacted with an existing enterprise integration system (EIS). The use cases for most common benchmarks that measure Java EE servers' performance and scalability — ECperf 1.1, SPECjbb2005, and SPECjAppServer2004 (see Resources ) — reflect this focus on B2C, B2B, and EIS. Similarly, the standard Java PetStore demo is a typical e-commerce application.

Many implicit and explicit assumptions about scalability in the Java EE architecture are reflected in the benchmarks:

- Request throughput is the most important characteristic that affects performance from the point of view of clients.

- Transaction duration is the most important factor in performance, and an application's overall performance can be improved by shortening each individual transaction it uses.

- Transactions are mostly independent of one another.

- Only a few business objects are affected by most transactions, except for long-living transactions.

- Transaction duration is limited by the application server's performance and the EISs deployed in the same administrative domain.

- Network-communication cost (when working with local resources) is adequately compensated for by connection pooling.

- Transaction duration can be shortened by investing in network configuration, hardware, and software.

- Content and data is under the application owner's control. With no dependencies on external services, the most important limiting factor for supplying content to the customer is bandwidth.

These assumptions resulted in the principles that the Java EE APIs are built on:

- Synchronous APIs . Java EE requires synchronous APIs for most purposes. (The heavyweight and cumbersome Java Message Service (JMS) API is virtually the only exception.) This requirement was dictated more by usability than performance reasons. A synchronous API is easy to use and can be made to have a low overhead. Serious problems can emerge quickly when heavy multithreading is required, so Java EE strongly discourages uncontrolled multithreading.

- Bounded thread pools . It was quickly discovered that a thread is an important resource and that the application-server performance degrades significantly if the number of threads surpasses some boundary. However, relying on an assumption that each operation is short, those operations can be distributed among a bounded number of threads to retain a high request throughput.

- Bounded connection pools . Using a single connection to a database makes optimal database performance difficult to obtain. Several database operations can be executed in parallel, but additional database connections speed up the application only to a point. At a certain number of connections, database performance degrades. Often, the number of database connections is smaller than the number of threads available in the servlet thread pool. Because of this, connection pools were created letting server components — such as servlets and Enterprise JavaBeans (EJB) — allocate a connection and return it to the pool afterward. If a connection is unavailable, the component waits for the connection blocking the current thread. Because other components work for only a short time with a connection, this delay is usually short.

- Fixed connections to resources . Applications are assumed to use only few external resources. The connection factory to each resource is obtained using the Java Naming and Directory Interface (JNDI) (or dependency injection in EJB 3.0). Practically, the only major Java EE API that supports connections to different EIS resources is the enterprise Web services API (see Resources ). Others mostly assume that the resources are fixed and that only additional data such as user credentials should be supplied to open connection operations.

In Web 1.0, these principles played out quite well. Some unique applications could be designed to fit within these boundaries. But they don't efficiently support the age of Web 2.0.

Change of landscape with Web 2.0

Web 2.0 applications have many unique requirements that make Java EE a difficult choice for their implementation. One aspect is that Web 2.0 applications use one another through services APIs more often than applications in the Web 1.0 world. A more significant element of a Web 2.0 application is a heavy inclination toward consumer-to-consumer (C2C) interaction: the application owner produces only a small part of the content; a larger portion is produced by users.

SOA + B2C + Web 2.0 = high latency

In a Web 2.0 context, mash-up applications frequently use services and feeds exposed through an SOA's service APIs (see Java EE meets SOA ). These applications need to consume services in a B2C context. For example, a mash-up might pull data — such as weather information, traffic information, and a map — from three unique sources. The time required to retrieve these three unique pieces of data adds to the overall request-processing time. Regardless of the growing number of data sources and service APIs, consumers still expect highly responsive applications.

Techniques such as caching can alleviate latency but are not applicable for all scenarios. For instance, it makes sense to cache map data to reduce response time, but it's often impossible or impractical to cache results of search queries or real-time traffic information.

By its nature, service invocation is a high-latency process that typically allocates only a small portion of CPU resources on the client and server. Most of the duration of a Web service invocation is caused by establishing a new connection and transmitting data. Therefore, improving performance on the client or the server sides usually does little to reduce the duration of the call.

By enabling user participation, Web 2.0 poses another challenge because applications have a much greater number of server requests per active user. This is true for several reasons:

- More relevant events occur because most events are caused by actions of other consumers, and consumers have much greater capacity to generate events. These events naturally cause more active use of Web applications by consumers.

- Applications provide a higher number of use cases to consumers. Web 1.0 consumers could simply browse a catalog, purchase an item, and track their order-processing status. Now, consumers can actively socialize with other consumers by participating in forums, chats, mash-ups, and so on, which causes higher traffic load.

- Today's applications are increasingly using Ajax to improve the user experience. A Web page using Ajax has a slower load time than a plain Web application's, because the page consists of static content, scripts (which can be fairly large), and a number of requests to the server. After loading, an Ajax page often creates several short requests to the server.

These factors usually cause a higher amount of traffic to the server and larger number of requests, compared with a typical Web 1.0 application. During high loads, this traffic is difficult to control. (However, Ajax also offers more opportunities for traffic optimization; Ajax-generated traffic volume is often smaller than the volume that would have been generated by a plain Web application supporting the same use cases.)

Web 2.0 applications are characterized by greater amount of content and larger size than previous-generation Web applications.

In the Web 1.0 world, content was typically published on a company's Web site only after the business entity explicitly approved it. The organization had control over every letter of the displayed text. So, if planned content violated infrastructure constraints relating to size, the content was optimized or split into several smaller chunks.

Web 2.0 sites, by their nature, don't restrict content size or creation. A large portion of Web 2.0 content is generated by users and communities. Organizations and companies simply provide the tools to enable contribution and content creation. Content is also increasing in size because of heavy use of images, audio, and video.

Establishing a new connection from a client to a server takes significant time. If several interactions are expected, it's more efficient to establish client/server communication once and reuse it. Persistent connections are also useful for sending client notifications. But Web 2.0 applications' clients are often behind firewalls, and it's often difficult or impossible to establish a direct connection from server to client. An Ajax application needs to send requests to poll for specific events. To reduce the number of poll requests, some Ajax applications use the Comet pattern (see Resources ): The server is designed to wait until an event occurs before sending a reply, while keeping a connection open.

Peer-to-peer messaging protocols such as SIP, BEEP, and XMPP increasingly use persistent connections. Streaming live video also benefits from a persistent connection.

Higher risk of the Slashdot effect

The fact that Web 2.0 applications can reach huge audiences makes some sites all the more vulnerable to the "Slashdot effect" — a tremendous spike in traffic load that occurs when the site is mentioned on a popular blog, news site, or social-networking site (see Resources ). All Web sites should be ready to handle traffic several orders of magnitude greater than normal load. And it's all the more important at such times that they be able to degrade gracefully under such high load.

Latency of operations affects Java EE applications more than operation throughput. Even if the services an application uses can handle a huge volume of operations, they do so while latency stays the same or increases. The current crop of Java EE APIs does not handle this situation well because it violates the assumptions about latency implicit in those APIs' designs.

Serving a large page for a forum or a blog takes up a processing thread when it uses a synchronous API. If each page takes one second to get served (consider applications, such as LiveJournal, that can have large pages), and you have 100 threads in a thread pool, you can't serve more than 100 pages per second — an unacceptable rate. Increasing the number of threads in the thread pool has limited benefit because application-server performance starts to degrade as the number of threads in the pool increases.

Java EE architecture can't take advantage of messaging protocols such SIP, BEEP, and XMPP because Java EE's synchronous API uses a single thread continuously. Because application servers use limited thread pools, continuous use of a thread prevents an application server from handling other requests while sending or receiving a message using these protocols. Note too that messages sent with these protocols are not necessarily short (particularly in the case of BEEP), and generating these messages can involve accessing resources deployed in other organizations, using Web services or other means. Also, transport protocols such as BEEP and Stream Control Transmission Protocol (SCTP) can have several simultaneous logical connections over a single TCP/IP connection, which makes the thread-management issue even more serious.

To implement streaming scenarios, Web applications have had to abandon standard Java EE patterns and APIs. As a result, Java EE application servers are rarely used for running P2P applications or streaming video. More often, custom components are developed to handle these protocols that often use Java Connector Architecture (JCA) connectors to implement proprietary asynchronous logic. (As you'll see later in this article, a new generation of servlet engines also supports some nonstandard interfaces for handling the Comet pattern. However, this support is radically different from standard servlet interfaces, in terms of both APIs and usage patterns.)

Finally, recall that one of the fundamental Java EE principles is that investment in network infrastructure can shorten transaction duration. In the case of live video feeds, though, an increase in network-infrastructure speed has absolutely no effect on a request's duration because the stream is sent to the client while it's being generated. Improvements to network infrastructure would only increase the number of streams to enable a larger number of clients and facilitate streaming at higher resolutions.

A possible way to avoid the issues we've discussed is to consider latency during application design and implement applications in an asynchronous, event-driven way. If the application is idle, it should not occupy finite resources such as threads. With asynchronous APIs, the application polls for external events and executes relevant actions when an event arrives. Typically, such an application is split into several event loops, each residing in its own thread.

An obvious gain from an asynchronous, event-driven design is that many operations waiting for external services can be executed in parallel as long as no data dependency exists between them. Asynchronous, event-driven architectures also have a massive scalability advantage over traditional synchronous designs, even if no parallel operations occur at all.

Asynchronous API benefits: A proof-of-concept model

The scalability gains from using asynchronous APIs can be illustrated using a simple model of the servlet process. (If you're already convinced that asynchronous design is the answer to Web 2.0 applications' scalability requirements, feel free to skip over this section to our discussion of available solutions to the Web 2.0 / Java EE conundrum.)

In our model, the servlet process does some work on the incoming request, queries a database, and then uses the information picked from the database to invoke a Web service. The final response is generated based on the Web service's response.

The model's servlet uses two kinds of resources with a relatively high latency. These resources differ by their characteristics and behavior under increasing load:

- Database connections This resource is usually available to Web applications as a

DataSourcewith a limited number of connections with which it's possible to work simultaneously. - Network connections. This resource is used for writing the response to the client and for invoking the Web service. Until recently, this resource was limited in most application servers. However, newer generations of application servers have started to use nonblocking I/O (NIO) to implement this resource, so we can assume that we have as many simultaneous network connections as needed. The model servlet uses this resource in the following situations:

-

Invoking the Web service. Although a destination server can handle a limited number of requests per second, this number is usually very high. The duration of the call is determined by network traffic.

-

Reading the request from the client. Our model ignores this cost because a HTTP

GETrequest is assumed. In this situation, the time needed to read the request from the client does not add to the servlet-request duration. -

Sending the response to the client. Our model ignores this cost because for short servlet responses, an application server can buffer the response in the memory and send it later to the client using NIO. And we assume that the response is a short one. In this situation, time needed to write the response to the client doesn't add to the servlet-request duration.

-

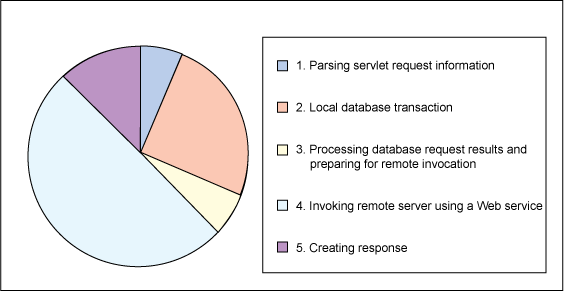

Let's assume that the servlet execution time is split into the stages shown in Table 1:

Table 1. Servlet operation timings (duration in abstract units)

| 2 units | Parsing servlet request information |

| 8 units | Local database transaction |

| 2 units | Processing database request results and preparing for remote invocation |

| 16 units | Invoking remote server using a Web service |

| 4 units | Creating response |

| 32 units |

Figure 1 shows the distribution among business logic, database, and Web services during execution:

Figure 1. Distribution of time among execution steps

These timings are selected to provide readable diagrams. In reality, most Web services would take much more time for processing. It's fair to state that we could be looking at a Web service processing time 100 to 300 times greater than that of business-logic Java code. To give the synchronous invocation model a chance, though, we've picked parameters that are very unlikely in reality, where either the Web service is extremely fast or the application server is very slow, or both.

Let's also assume that we have the connection-pool capacity equal to two. Therefore, only two database transactions can occur at the same time. (Actual numbers of threads and connections would be bigger in the case of a real application server.)

We also assume that Web service invocations take the same time and can all be done in parallel. This is a realistic assumption because Web service interaction duration consists of sending data back and forth. Doing actual work is just a small fraction of the Web service call.

Given this scenario, both synchronous and asynchronous cases will behave the same under low loads. If database query and Web service invocation could occur in parallel, the asynchronous case would behave better. The interesting results occur in an overload situation, such as a sudden access peak. Let's assume nine simultaneous requests. For the synchronous case, the servlet engine thread pool has three threads. For the asynchronous case, we'll use only one thread.

Note that in both cases, all nine connections are accepted as they arrive (as happens with most servlet engines now). However, no processing happens in the synchronous case for the other six accepted connections while the first three are processed.

Figures 2 and 3 were created using a simple simulation program that models both synchronous and asynchronous API cases, respectively:

(Click here for the full image. )

Each rectangle in Figure 2 represents one step of the process. The first number in the rectangle is a process number (1 through 9), and the second number is the phase number within a process. Each process is marked with a unique color. Note that database and Web service operations are on separate lines because they are executed by the database engine and Web service implementation. The servlet engine does nothing while it waits for results. Light-gray areas represent the idle (waiting) state.

The diamond-shaped markers at the bottom of the diagram indicate that one or more requests are completed at this point. The marker's first number represents time in abstract units; the second optional number enclosed in parenthesis is the number of requests that terminate at this point. In Figure 2, you can see that the first two requests finish at point 32 and the last one finishes at the point 104.

Now let's assume that the database and the Web service client runtime support asynchronous interfaces. We also assume that all asynchronous servlets use a single thread (although asynchronous interfaces are perfectly capable of making use of additional threads if they are available). Figure 3 shows the results:

(Click here for the full image. )

There are a few interesting things to note in Figure 3. The first request finishes 23% later than in the synchronous case. However, the last one finishes 26% faster. And this happens when three times fewer threads were used. The request-execution time is distributed much more regularly, so users will receive pages at more regular speed. The difference between the processing time for the first and the last request is 80%. In the case of synchronous interfaces, it is 225%.

Let's now assume that we have upgraded the application and database servers so they work twice as fast. Table 2 shows the timing results (with units relative to those in Table 1):

Table 2. Servlet operation timings after upgrade

| 1 unit | Parsing servlet request information |

| 4 units | Local database transaction |

| 1 units | Processing database request results and preparing for remote invocation |

| 16 units | Invoking remote server using a Web service |

| 2 units | Creating response |

| 32 units |

You can see that the overall individual request-processing time is 24 time units, which is about 3/4 of the original request duration.

Figure 4 shows the new distribution among business logic, database, and Web services:

Figure 4. Distribution of time between steps after upgrade

Figure 5 shows the results after synchronous processing. You can see that the overall execution duration has decreased by about 25%. However, the steps' distribution pattern has not changed much, and servlet threads spend even more time in a waiting state.

Figure 5. Synchronous case after upgrade

(Click here for the full image. )

Figure 6 shows the results after processing with the asynchronous API:

Figure 6. Asynchronous case after upgrade

(Click here for the full image. )

The results in the asynchronous case are very interesting. Processing scales much better with the database and application server performance increase. Fairness has improved, and the difference between the worst and the best request processing times is only 57%. Total processing time (when the last request is ready) is 57% of the original time before the upgrade. This is a significant improvement compared to the 75% for the synchronous case. The last request (request 9 in both cases) is completed more than 40% faster than in the synchronous case, and the first request is just 14% slower than in the synchronous case. In addition, in the asynchronous case, it's possible to execute a greater number of parallel Web service operations. In the synchronous case, this level of parallelism isn't achievable, because the limiting factor is the number of threads in the servlet thread pool. Even if the Web service is capable of handling more requests, the servlet can't send them because it is not yet active.

The real-world test results confirm that asynchronous applications scale better and handle overload situations more gracefully. Latency is a very difficult problem to solve, and Moore's Law (see Resources ) does not give us much hope here. Most modern computing improvements increase the required bandwidth. Latency in most cases either stays the same or even is somewhat worsened. This is why developers are trying to introduce asynchronous interfaces into application servers.

Many options are now available for implementing asynchronous systems, but no single pattern has established itself as a de facto standard. Each approach has its own advantages and disadvantages, and they might play out differently in different situations. The remainder of this article gives an overview — including pros and cons — of mechanisms that let you construct asynchronous, event-driven applications using the Java platform.

Some attempts have been made to enable asynchronous interactions in a generic way on the Java platform. All these attempts are based on a message-passing communication model. Many of them use some variation of the actor model to define the objects. Otherwise, these frameworks differ greatly in usability, available libraries, and approach. See Resources for links to these project's Web sites and related information.

Staged event-driven architecture

Staged event-driven architecture (SEDA) is an interesting framework that combines the ideas of asynchronous programming and autonomic computing. SEDA was one of the biggest inputs for Java NIO API introduced in J2SE 1.4. The project itself has been discontinued, but SEDA sets a new benchmark for scalability and adaptability of Java applications, and its ideas about asynchronous APIs have influenced other projects.

SEDA tries to combine asynchronous and synchronous API design, with interesting results. The framework is much more usable than ad-hoc concurrency , but it hasn't been usable enough to win user mind share.

In SEDA, an application is divided into stages . Each stage is a component that has a number of threads. The request is dispatched to a stage and then is handled there. The stage can regulate its own capacity in several ways:

- Increase and decrease the number of used threads depending on load. This allows per-component dynamic adaptation of the server to actual usage. If some component experiences a usage surge, it allocates more threads. If it is idle, the number of threads is reduced.

- Change its behavior depending on the load. For example, simpler versions of pages can be generated depending on the load. The page could avoid using images, contain fewer scripts, disable nonessential functionality, and so on. Users can still use the application, but they generate fewer requests and less traffic.

- Block stages that try to put a request on it or simply refuse to accept a request.

The first two ideas are great ones and are a smart application of autonomic-computing ideas. The third, however, contributes to the reasons why the framework has not been widely adopted. It introduces a point of failure by adding the risk of a deadlock unless extra caution is exercised during application design. Other reasons why the framework is hard to use include:

- A stage is a very coarse-grained component. An example stage is network interface and HTTP support. It's hard to solve problems such as limited bandwidth of some clients while working with the network layer as a whole.

- There's no easy way to return the result of an asynchronous call. The result is simply dispatched to the stage, in hope that the stage will find the correlating operation state itself.

- Most currently available Java libraries are synchronous. The framework doesn't try to isolate synchronous code from asynchronous code in a consistent way, making it dangerously easy to write code that accidentally blocks the entire stage.

The most-deployed implementation of the SEDA project's ideas is the probably the Apache MINA framework (see Resources ). It is used for implementation of the OSFlash.org Red5 streaming server, the Apache Directory Project, and the Jive Software Openfire XMPP Server.

Strictly speaking, the E programming language is a dynamically typed functional programming language, not a framework. Its focus is on providing secure distributed computing, and it also provides interesting constructs for asynchronous programming. The language claims Joule and Concurrent Prolog among its predecessors in this area, but its concurrency support and overall syntax look more natural and friendly to programmers with backgrounds in mainstream programming languages such the Java language, JavaScript, and C#.

The language is currently implemented over Java and Common-Lisp. It can be used from Java applications. However, several barriers stand in the way of its adoption for heavy-duty, server-side applications today. Most of the problems are due to its early stage of development and will likely be fixed later. Other issues are caused by the language's dynamic nature, but these issues are mostly orthogonal to concurrency extensions the language offers.

E has the following core language constructs to support asynchronous programming:

- A vat is a container for objects. All objects live in the context of some vat, and they can't be synchronously accessed from other vats.

- A promise is a variable that represents the outcome of some asynchronous operation. Initially, it is in unresolved state, meaning that the operation is not finished yet. It resolves to some value or is smashed with failure after completion of the operation.

- Any object can receive messages, and they can be invoked locally. Local objects might be invoked synchronously using the immediate call operation or asynchronously using the eventual send operation. Remote objects can be invoked only using the eventual send operation. Eventual invocation creates a promise. The

.operator is used for immediate invocations and<-for eventual ones. - Promises can also be created explicitly. In that case a reference to the resolver object is provided that can be passed to other vats. This object has two methods:

resolveandsmash. - A

whenoperator lets you invoke some code when a promise isresolved orsmashed. The code in thewhenoperator is treated as a closure and is executed with access to definitions from enclosing scope. This is similar to the way anonymous inner Java classes can access some method-scope definitions.

These few constructs provide a surprisingly powerful and usable system that allows easy creation of asynchronous components. Even if the language isn't used in a production environment, it's useful for prototyping complex concurrency problems. It enforces a message-passing discipline and provides convenient syntax for handling concurrency problems. Its operators are nothing magical, and they can be emulated in other programming languages, albeit with resulting code that will likely lack the elegance and the simplicity of the original.

E raises the bar for usability of asynchronous programming. Concurrency support in this language is quite orthogonal to other language features, and it might be retrofitted into existing languages. The language features are already being discussed in context of the development of Squeak, Python, and Erlang. It would be likely more useful than more domain-specific language features such as iterators in C#.

The AsyncObjects framework project focuses on creating a usable asynchronous component framework in pure Java code. The framework is an attempt to bring together SEDA and the E programming language. Like E, it provides basic concurrency mechanisms. And like SEDA, it provides mechanisms to integrate with the synchronous Java API. The first prototype version of the framework was released in 2002. Development has been mostly stale since that time, but the work on the project recently resumed. E has shown how usable asynchronous programming can be, and this framework tries to be as usable as possible while staying pure Java code.

As in SEDA, the application is split into several event loops. However, no SEDA-like self-management features have been implemented in the project yet. Differently from SEDA, it uses a simpler load-management mechanism for I/O because components are much more fine-grained and promises are used to receive results of operations.

The framework implements the same concepts of asynchronous component, vat, and promise as the E programming language. Because new operators can't be introduced in pure Java code, an arbitrary object can't be an asynchronous component. The implementation has to extend a certain base class, and there should be an asynchronous interface that the framework implements. This framework-provided implementation of the asynchronous interface sends messages to the component's vat, and the vat later dispatches messages to the component.

The current version (0.3.2) is compatible with Java 5 and supports generics. Java NIO is used if it is available for the current platform. However, the framework is able to fall back to plain sockets.

The biggest problem with this framework is that the class library is poor because it's difficult to integrate with the synchronous Java API. Currently, only the network I/O library is implemented. However, recent improvements in this area — such as asynchronous Web services in Axis2 and Comet Servlets in Tomcat 6 described later (see Servlet-specific or IO-specific APIs ) — can simplify such integration.

Waterken's ref_send framework is another attempt to implement E ideas in Java programming. It is mostly implemented using a subset of the Java language named Joe-E.

The library provides support for eventual invocation of operations. However, this support looks less automated than the one in AsyncObjects. Thread safety in the current version of the framework is also questionable.

Only core classes and very small samples are released, and there are no significant applications and class libraries. So it is not yet clear how the ideas of the framework will play out on a larger scale. The authors claim that a full Web server has been implemented and will be released soon. Once it's released, it will be interesting to revisit this framework.

Frugal Mobile Objects is another framework based on the actor model. It targets resource-constrained environments such as Java ME CLDC 1.1. It uses interesting design patterns to reduce resource usage while keeping interfaces reasonably simple.

This framework demonstrates that applications might benefit from asynchronous designs when faced with performance and scalability problems — even in a resource-constrained environment.

The API provided by the framework looks quite cumbersome, but it is possibly justified by the constraints of the framework's target environment.

Scala is another programming language for the Java platform. It provides a superset of Java features, but in a slightly different syntax. It features several usability enhancements compared with the plain Java programming language.

One of its interesting features is the actor-based concurrency support that is modeled after the Erlang programming language. The design looks like it is not yet finalized, but this feature is relatively usable and supported by the language syntax. However, Scala's Erlang-like concurrency support is somewhat less usable and automated than E's concurrency support.

The Scala model also has security issues because reference to the caller is passed with every message. This makes it possible for the invoked component to invoke all operations of the invoking component, instead of just returning the value. E's promise model is more granular in this respect. The mechanism used to communicate with blocking code is not completely developed yet.

The advantage of Scala is that it compiles to JVM bytecode. Theoretically, it can be used by Java SE and Java EE applications as is without any performance penalties. However, suitability for commercial deployment should be determined separately because Scala has limited IDE support and, unlike the Java language, is not backed by vendors. So it might be an interesting platform for short-lifetime projects such as prototypes, but it can be risky to use for projects that are expected to have longer lifetimes.

Servlet-specific or I/O-specific APIs

Because the problems we've described are most acute at the servlet, Web services, and general I/O level, several projects propose to address the issue there. The biggest drawback of these solutions is that they try to solve the problem only for a limited category of applications. Even if it's possible to make an asynchronous servlet, it's almost useless without the ability to make an asynchronous call to local and remote resources. It should be also possible to write an asynchronous model and business-logic code as well. Another common problem is the usability of the proposed solutions, which is usually lower than for generic solutions.

However, these attempts are notable as recognition of the problem of implementing asynchronous components. See Resources for links to these project's Web sites and related information.

JSR 203 is a revision of the NIO API. At the time of writing this article it is still in the early draft stage and might change significantly during the development process. The API is targeted for inclusion in Java 7.

JSR 203 introduces a notion of asynchronous channels . It is designed to address many programmer woes, but it looks like the API stays rather low-level. It finally introduces the asynchronous File I/O API that has been missing in previous versions, and the notions of IoFuture and CompletionHandler make it easier to use classes from other frameworks. Generally, the new asynchronous NIO API is more usable than the selector-based one from the previous-generation API. And it even might be possible to use it for simple tasks directly, without writing custom wrappers.

However, a big disadvantage of this JSR is that it is highly specific to file and socket I/O. It does not provide building blocks to create higher-level asynchronous components. The high-level classes might be built, but they have to provide their own ways of doing the same things. This looks like a good technical decision, considering that there's still no standard way to develop asynchronous components in the Java language.

Glassfish Grizzly NIO support is similar to the SEDA framework's, and it inherits most of SEDA problems. However, it is more specialized to support I/O tasks. The provided API is higher-level than the plain NIO API, but it's still cumbersome to use.

Jetty continuations is a highly nontraditional approach. Usage of exceptions for implementation of a control flow is a rather questionable approach for an API. (You can see other views in Greg Wilkins' blog, which is linked to in the Resources section.)The servlet might request a continuation object and call the suspend() method with a specified timeout on it. This operation throws an exception. Then a resume operation can be invoked on continuation, or the continuation resumes automatically after the specified time.

So Jetty tries to implement a synchronous-looking API with asynchronous semantics. However, this behavior will break the expectations of the client because the servlet will resume at the start of the method, rather than at point where suspend() was called.

The Tomcat Comet API is specifically designed to support the Comet interaction pattern. The servlet engine notifies the servlet about its state transitions and whether data is available for reading. This is a more sane and straightforward approach than the one Jetty uses. The approach uses the traditional synchronous API for writing and reading from streams. Implemented in such a manner, the API would not block if used carefully.

JAX WS 2.0 and Apache Axis2 Asynchronous Web Service Client API

JAX WS 2.0 and Axis2 provide API support for nonblocking invocation of Web services. The Web service engine notifies the supplied listener when the Web service operation finishes. This opens new opportunities for Web service usage — even from Web clients. If there are several independent invocations of Web services from one servlet, they all can be done in parallel, so the overall delay on the client is shorter.

The need for asynchronous Java components is being recognized now, and the area of asynchronous applications is under active development. Both major open source servlet engines (Tomcat and Jetty) provide some support at least for servlets, where developers are feeling the most pain. Although Java libraries are starting to provide asynchronous interfaces, these interfaces lack a common theme, and it's difficult to make them compatible with one another because of thread management and other issues. This creates a need for containers that can host a multitude of different asynchronous components provided by different parties.

Currently users are left with a number of choices that each have advantages and disadvantages in different situations. Apache MINA is an example of a library that provides support for some popular network protocols out of the box, so it might be a good choice when these protocols are required. Apache Tomcat 6 has good support for the Comet interaction pattern, making it an attractive option when asynchronous interactions are limited to this pattern. If you're creating an application from scratch and it's clear that existing libraries may not benefit it much, the AsyncObjects framework might be a good choice because it provides a variety of usable interfaces. This framework might be also useful for creating wrappers around existing asynchronous component libraries.

It's time to create a JSR that focuses on creating a common asynchronous programming framework for the Java language. Then there will be a long road ahead integrating existing asynchronous components into this framework and creating an asynchronous version of existing synchronous interfaces. With each step, the scalability of enterprise Java applications will improve, and we'll be able to face the challenges that lie beyond that. The continuously growing Internet population and continuous diffusion of network services in our everyday activities will certainly provide us with many such challenges.

- Read about the ECPerf 1.1 , SPECjbb2005 , and SPECjAppServer2004 standard Java EE benchmarks.

- Take a look at Greg Wilkins' blog .

- "Ease the integration of Ajax and Java EE " (Patrick Gan, developerWorks, July 2006) examines the potential impacts throughout the full development life cycle of introducing Ajax technology into Java EE Web applications.

- JSR 109: Implementing Enterprise Web Services defines the programming model and runtime architecture for implementing Web services in the Java language.

- "Why Ajax Comet? " (Greg Wilkins, webtide, July 2006) is a description of the Comet pattern.

- "The Slashdot Effect: An Analysis of Three Internet Publications " by Stephen Adler is a good overview of Slashdot effect.

- "SEDA: An Architecture for WellConditioned, Scalable Internet Services " (Matt Welsh, David Culler, and Eric Brewer, University of California, Berkeley) is a good overview of SEDA and provides information about benefits of asynchronous application design.

- Wikipedia explains Moore's Law .

- Check out the Apache MINA project site.

- Visit the SEDA site.

- ERights.org is the home of the E programming language. The book The E Language in a Walnut , available there, covers E basics.

- Visit the AsyncObjects Framework Home Page .

- Learn more about

ref_sendat the Waterken Server site.

- "Frugal Mobile Objects " by Benoit Garbinato et al. describes the Frugal Mobile Objects framework.

- Check out the Scala Programming Language .

- "Actors that Unify Threads and Events " (Philipp Haller and Martin Odersky, January 2007) describes concurrency support introduced in recent versions of Scala.

- JSR 203: More New I/O APIs for the Java Platform ("NIO.2") defines APIs for filesystem access, scalable asynchronous I/O operations, socket-channel binding and configuration, and multicast datagrams.

- "Grizzly NIO Architecture: part II " (Jean-Francois Arcand, java.net, January 2006) and "Grizzly part III: Asynchronous Request Processing (ARP) " (Jean-Francois Arcand, java.net, February 2006) describe Grizzly's architecture.

- Get the scoop on http://docs.codehaus.o