Comparing Two High-Performance I/O Design Patterns

by Alexander Libman with Vladimir Gilbourd

November 25, 2005

System I/O can be blocking, or non-blocking synchronous, or non-blocking asynchronous [1, 2]. Blocking I/O means that the calling system does not return control to the caller until the operation is finished. As a result, the caller is blocked and cannot perform other activities during that time. Most important, the caller thread cannot be reused for other request processing while waiting for the I/O to complete, and becomes a wasted resource during that time. For example, a read() operation on a socket in blocking mode will not return control if the socket buffer is empty until some data becomes available.

By contrast, a non-blocking synchronous call returns control to the caller immediately. The caller is not made to wait, and the invoked system immediately returns one of two responses: If the call was executed and the results are ready, then the caller is told of that. Alternatively, the invoked system can tell the caller that the system has no resources (no data in the socket) to perform the requested action. In that case, it is the responsibility of the caller may repeat the call until it succeeds. For example, a read() operation on a socket in non-blocking mode may return the number of read bytes or a special return code -1 with errno set to EWOULBLOCK/EAGAIN, meaning "not ready; try again later."

In a non-blocking asynchronous call, the calling function returns control to the caller immediately, reporting that the requested action was started. The calling system will execute the caller's request using additional system resources/threads and will notify the caller (by callback for example), when the result is ready for processing. For example, a Windows ReadFile() or POSIX aio_read() API returns immediately and initiates an internal system read operation. Of the three approaches, this non-blocking asynchronous approach offers the best scalability and performance.

This article investigates different non-blocking I/O multiplexing mechanisms and proposes a single multi-platform design pattern/solution. We hope that this article will help developers of high performance TCP based servers to choose optimal design solution. We also compare the performance of Java, C# and C++ implementations of proposed and existing solutions. We will exclude the blocking approach from further discussion and comparison at all, as it the least effective approach for scalability and performance.

Reactor and Proactor: two I/O multiplexing approaches

In general, I/O multiplexing mechanisms rely on an event demultiplexor [1, 3], an object that dispatches I/O events from a limited number of sources to the appropriate read/write event handlers. The developer registers interest in specific events and provides event handlers, or callbacks. The event demultiplexor delivers the requested events to the event handlers.

Two patterns that involve event demultiplexors are called Reactor and Proactor [1]. The Reactor patterns involve synchronous I/O, whereas the Proactor pattern involves asynchronous I/O. In Reactor, the event demultiplexor waits for events that indicate when a file descriptor or socket is ready for a read or write operation. The demultiplexor passes this event to the appropriate handler, which is responsible for performing the actual read or write.

In the Proactor pattern, by contrast, the handler—or the event demultiplexor on behalf of the handler—initiates asynchronous read and write operations. The I/O operation itself is performed by the operating system (OS). The parameters passed to the OS include the addresses of user-defined data buffers from which the OS gets data to write, or to which the OS puts data read. The event demultiplexor waits for events that indicate the completion of the I/O operation, and forwards those events to the appropriate handlers. For example, on Windows a handler could initiate async I/O (overlapped in Microsoft terminology) operations, and the event demultiplexor could wait for IOCompletion events [1]. The implementation of this classic asynchronous pattern is based on an asynchronous OS-level API, and we will call this implementation the "system-level" or "true" async, because the application fully relies on the OS to execute actual I/O.

An example will help you understand the difference between Reactor and Proactor. We will focus on the read operation here, as the write implementation is similar. Here's a read in Reactor:

- An event handler declares interest in I/O events that indicate readiness for read on a particular socket

- The event demultiplexor waits for events

- An event comes in and wakes-up the demultiplexor, and the demultiplexor calls the appropriate handler

- The event handler performs the actual read operation, handles the data read, declares renewed interest in I/O events, and returns control to the dispatcher

By comparison, here is a read operation in Proactor (true async):

- A handler initiates an asynchronous read operation (note: the OS must support asynchronous I/O). In this case, the handler does not care about I/O readiness events, but is instead registers interest in receiving completion events.

- The event demultiplexor waits until the operation is completed

- While the event demultiplexor waits, the OS executes the read operation in a parallel kernel thread, puts data into a user-defined buffer, and notifies the event demultiplexor that the read is complete

- The event demultiplexor calls the appropriate handler;

- The event handler handles the data from user defined buffer, starts a new asynchronous operation, and returns control to the event demultiplexor.

Current practice

The open-source C++ development framework ACE [1, 3] developed by Douglas Schmidt, et al., offers a wide range of platform-independent, low-level concurrency support classes (threading, mutexes, etc). On the top level it provides two separate groups of classes: implementations of the ACE Reactor and ACE Proactor. Although both of them are based on platform-independent primitives, these tools offer different interfaces.

The ACE Proactor gives much better performance and robustness on MS-Windows, as Windows provides a very efficient async API, based on operating-system-level support [4, 5].

Unfortunately, not all operating systems provide full robust async OS-level support. For instance, many Unix systems do not. Therefore, ACE Reactor is a preferable solution in UNIX (currently UNIX does not have robust async facilities for sockets). As a result, to achieve the best performance on each system, developers of networked applications need to maintain two separate code-bases: an ACE Proactor based solution on Windows and an ACE Reactor based solution for Unix-based systems.

As we mentioned, the true async Proactor pattern requires operating-system-level support. Due to the differing nature of event handler and operating-system interaction, it is difficult to create common, unified external interfaces for both Reactor and Proactor patterns. That, in turn, makes it hard to create a fully portable development framework and encapsulate the interface and OS- related differences.

Proposed solution

In this section, we will propose a solution to the challenge of designing a portable framework for the Proactor and Reactor I/O patterns. To demonstrate this solution, we will transform a Reactor demultiplexor I/O solution to an emulated async I/O by moving read/write operations from event handlers inside the demultiplexor (this is "emulated async" approach). The following example illustrates that conversion for a read operation:

- An event handler declares interest in I/O events (readiness for read) and provides the demultiplexor with information such as the address of a data buffer, or the number of bytes to read.

- Dispatcher waits for events (for example, on select());

- When an event arrives, it awakes up the dispatcher. The dispatcher performs a non- blocking read operation (it has all necessary information to perform this operation) and on completion calls the appropriate handler.

- The event handler handles data from the user-defined buffer, declares new interest, along with information about where to put the data buffer and the number bytes to read in I/O events. The event handler then returns control to the dispatcher.

As we can see, by adding functionality to the demultiplexor I/O pattern, we were able to convert the Reactor pattern to a Proactor pattern. In terms of the amount of work performed, this approach is exactly the same as the Reactor pattern. We simply shifted responsibilities between different actors. There is no performance degradation because the amount of work performed is still the same. The work was simply performed by different actors. The following lists of steps demonstrate that each approach performs an equal amount of work:

Standard/classic Reactor:

- Step 1) wait for event (Reactor job)

- Step 2) dispatch "Ready-to-Read" event to user handler ( Reactor job)

- Step 3) read data (user handler job)

- Step 4) process data ( user handler job)

Proposed emulated Proactor:

- Step 1) wait for event (Proactor job)

- Step 2) read data (now Proactor job)

- Step 3) dispatch "Read-Completed" event to user handler (Proactor job)

- Step 4) process data (user handler job)

With an operating system that does not provide an async I/O API, this approach allows us to hide the reactive nature of available socket APIs and to expose a fully proactive async interface. This allows us to create a fully portable platform-independent solution with a common external interface.

TProactor

The proposed solution (TProactor) was developed and implemented at Terabit P/L [6]. The solution has two alternative implementations, one in C++ and one in Java. The C++ version was built using ACE cross-platform low-level primitives and has a common unified async proactive interface on all platforms.

The main TProactor components are the Engine and WaitStrategy interfaces. Engine manages the async operations lifecycle. WaitStrategy manages concurrency strategies. WaitStrategy depends on Engine and the two always work in pairs. Interfaces between Engine and WaitStrategy are strongly defined.

Engines and waiting strategies are implemented as pluggable class-drivers (for the full list of all implemented Engines and corresponding WaitStrategies, see Appendix 1). TProactor is a highly configurable solution. It internally implements three engines (POSIX AIO, SUN AIO and Emulated AIO) and hides six different waiting strategies, based on an asynchronous kernel API (for POSIX- this is not efficient right now due to internal POSIX AIO API problems) and synchronous Unix select(), poll(), /dev/poll (Solaris 5.8+), port_get (Solaris 5.10), RealTime (RT) signals (Linux 2.4+), epoll (Linux 2.6), k-queue (FreeBSD) APIs. TProactor conforms to the standard ACE Proactor implementation interface. That makes it possible to develop a single cross-platform solution (POSIX/MS-WINDOWS) with a common (ACE Proactor) interface.

With a set of mutually interchangeable "lego-style" Engines and WaitStrategies, a developer can choose the appropriate internal mechanism (engine and waiting strategy) at run time by setting appropriate configuration parameters. These settings may be specified according to specific requirements, such as the number of connections, scalability, and the targeted OS. If the operating system supports async API, a developer may use the true async approach, otherwise the user can opt for an emulated async solutions built on different sync waiting strategies. All of those strategies are hidden behind an emulated async façade.

For an HTTP server running on Sun Solaris, for example, the /dev/poll or port_get()-based engines is the most suitable choice, able to serve huge number of connections, but for another UNIX solution with a limited number of connections but high throughput requirements, a select()-based engine may be a better approach. Such flexibility cannot be achieved with a standard ACE Reactor/Proactor, due to inherent algorithmic problems of different wait strategies (see Appendix 2).

In terms of performance, our tests show that emulating from reactive to proactive does not impose any overhead—it can be faster, but not slower. According to our test results, the TProactor gives on average of up to 10-35 % better performance (measured in terms of both throughput and response times) than the reactive model in the standard ACE Reactor implementation on various UNIX/Linux platforms. On Windows it gives the same performance as standard ACE Proactor.

Performance comparison (JAVA versus C++ versus C#).

In addition to C++, as we also implemented TProactor in Java. As for JDK version 1.4, Java provides only the sync-based approach that is logically similar to C select() [7, 8]. Java TProactor is based on Java's non-blocking facilities (java.nio packages) logically similar to C++ TProactor with waiting strategy based on select().

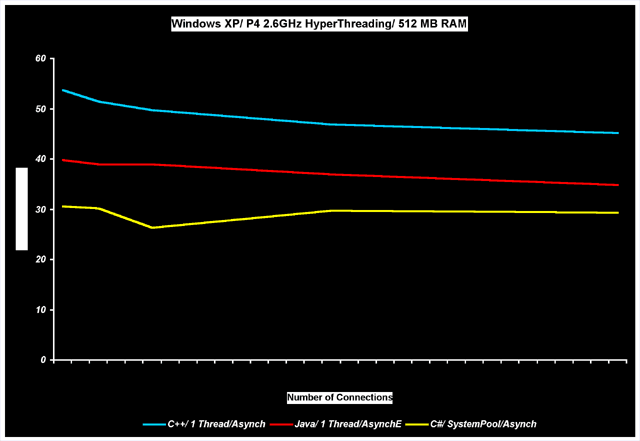

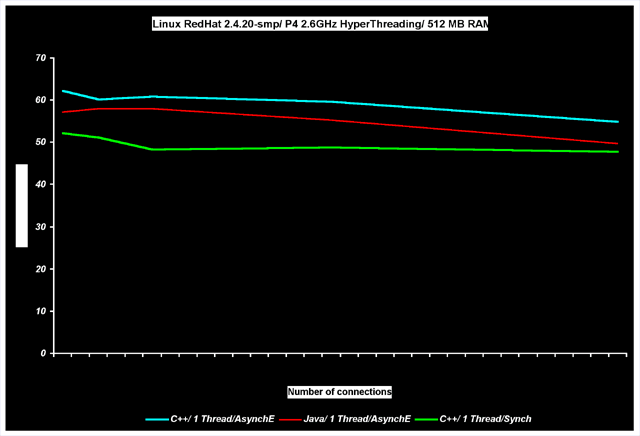

Figures 1 and 2 chart the transfer rate in bits/sec versus the number of connections. These charts represent comparison results for a simple echo-server built on standard ACE Reactor, using RedHat Linux 9.0, TProactor C++ and Java (IBM 1.4JVM) on Microsoft's Windows and RedHat Linux9.0, and a C# echo-server running on the Windows operating system. Performance of native AIO APIs is represented by "Async"-marked curves; by emulated AIO (TProactor)—AsyncE curves; and by TP_Reactor—Synch curves. All implementations were bombarded by the same client application—a continuous stream of arbitrary fixed sized messages via N connections.

The full set of tests was performed on the same hardware. Tests on different machines proved that relative results are consistent.

User code example

The following is the skeleton of a simple TProactor-based Java echo-server. In a nutshell, the developer only has to implement the two interfaces: OpRead with buffer where TProactor puts its read results, andOpWrite with a buffer from which TProactor takes data. The developer will also need to implement protocol-specific logic via providing callbacks onReadCompleted() and onWriteCompleted() in theAsynchHandler interface implementation. Those callbacks will be asynchronously called by TProactor on completion of read/write operations and executed on a thread pool space provided by TProactor (the developer doesn't need to write his own pool).

class EchoServerProtocol implements AsynchHandler

{

AsynchChannel achannel = null;

EchoServerProtocol( Demultiplexor m, SelectableChannel channel ) throws Exception

{

this.achannel = new AsynchChannel( m, this, channel );

}

public void start() throws Exception

{

// called after construction

System.out.println( Thread.currentThread().getName() + ": EchoServer protocol started" );

achannel.read( buffer);

}

public void onReadCompleted( OpRead opRead ) throws Exception

{

if ( opRead.getError() != null )

{

// handle error, do clean-up if needed

System.out.println( "EchoServer::readCompleted: " + opRead.getError().toString());

achannel.close();

return;

}

if ( opRead.getBytesCompleted () <= 0)

{

System.out.println( "EchoServer::readCompleted: Peer closed " + opRead.getBytesCompleted();

achannel.close();

return;

}

ByteBuffer buffer = opRead.getBuffer();

achannel.write(buffer);

}

public void onWriteCompleted(OpWrite opWrite) throws Exception

{

// logically similar to onReadCompleted

...

}

}

IOHandler is a TProactor base class. AsynchHandler and Multiplexor, among other things, internally execute the wait strategy chosen by the developer.

Conclusion

TProactor provides a common, flexible, and configurable solution for multi-platform high- performance communications development. All of the problems and complexities mentioned in Appendix 2, are hidden from the developer.

It is clear from the charts that C++ is still the preferable approach for high performance communication solutions, but Java on Linux comes quite close. However, the overall Java performance was weakened by poor results on Windows. One reason for that may be that the Java 1.4 nio package is based on select()-style API. � It is true, Java NIO package is kind of Reactor pattern based on select()-style API (see [7, 8]). Java NIO allows to write your own select()-style provider (equivalent of TProactor waiting strategies). Looking at Java NIO implementation for Windows (to do this enough to examine import symbols in jdk1.5.0\jre\bin\nio.dll), we can make a conclusion that Java NIO 1.4.2 and 1.5.0 for Windows is based on WSAEventSelect () API. That is better than select(), but slower than IOCompletionPort�s for significant number of connections. . Should the 1.5 version of Java's nio be based on IOCompletionPorts, then that should improve performance. If Java NIO would use IOCompletionPorts, than conversion of Proactor pattern to Reactor pattern should be made inside nio.dll. Although such conversion is more complicated than Reactor- >Proactor conversion, but it can be implemented in frames of Java NIO interfaces. (this the topic of next arcticle, but we can provide algorithm). At this time, no TProactor performance tests were done on JDK 1.5.

Note. All tests for Java are performed on "raw" buffers (java.nio.ByteBuffer) without data processing.

Taking into account the latest activities to develop robust AIO on Linux [9], we can conclude that Linux Kernel API (io_xxxx set of system calls) should be more scalable in comparison with POSIX standard, but still not portable. In this case, TProactor with new Engine/Wait Strategy pair, based on native LINUX AIO can be easily implemented to overcome portability issues and to cover Linux native AIO with standard ACE Proactor interface.

Appendix I

Engines and waiting strategies implemented in TProactor

| Engine Type | Wait Strategies | Operating System |

|---|---|---|

| POSIX_AIO (true async) aio_read()/aio_write() |

aio_suspend() Waiting for RT signal Callback function |

POSIX complained UNIX (not robust) POSIX (not robust) SGI IRIX, LINUX (not robust) |

| SUN_AIO (true async) aio_read()/aio_write() |

aio_wait() | SUN (not robust) |

| Emulated Async Non-blocking read()/write() |

select() poll() /dev/poll Linux RT signals Kqueue |

generic POSIX Mostly all POSIX implementations SUN Linux FreeBSD |

Appendix II

All sync waiting strategies can be divided into two groups:

- edge-triggered (e.g. Linux RT signals)—signal readiness only when socket became ready (changes state);

- level-triggered (e.g. select(), poll(), /dev/poll)—readiness at any time.

Let us describe some common logical problems for those groups:

- edge-triggered group: after executing I/O operation, the demultiplexing loop can lose the state of socket readiness. Example: the "read" handler did not read whole chunk of data, so the socket remains still ready for read. But the demultiplexor loop will not receive next notification.

- level-triggered group: when demultiplexor loop detects readiness, it starts the write/read user defined handler. But before the start, it should remove socket descriptior from the set of monitored descriptors. Otherwise, the same event can be dispatched twice.

- Obviously, solving these problems adds extra complexities to development. All these problems were resolved internally within TProactor and the developer should not worry about those details, while in the synch approach one needs to apply extra effort to resolve them.

Resources

[1] Douglas C. Schmidt, Stephen D. Huston "C++ Network Programming." 2002, Addison-Wesley ISBN 0-201-60464-7

[2] W. Richard Stevens "UNIX Network Programming" vol. 1 and 2, 1999, Prentice Hill, ISBN 0-13- 490012-X

[3] Douglas C. Schmidt, Michael Stal, Hans Rohnert, Frank Buschmann "Pattern-Oriented Software Architecture: Patterns for Concurrent and Networked Objects, Volume 2" Wiley & Sons, NY 2000

[4] INFO: Socket Overlapped I/O Versus Blocking/Non-blocking Mode. Q181611. Microsoft Knowledge Base Articles.

[5] Microsoft MSDN. I/O Completion Ports.

http://msdn.microsoft.com/library/default.asp?url=/library/en- us/fileio/fs/i_o_completion_ports.asp

[6] TProactor (ACE compatible Proactor).

www.terabit.com.au

[7] JavaDoc java.nio.channels

http://java.sun.com/j2se/1.4.2/docs/api/java/nio/channels/package-summary.html

[8] JavaDoc Java.nio.channels.spi Class SelectorProvider

http://java.sun.com/j2se/1.4.2/docs/api/java/nio/channels/spi/SelectorProvider.html

[9] Linux AIO development

http://lse.sourceforge.net/io/aio.html, and

http://archive.linuxsymposium.org/ols2003/Proceedings/All-Reprints/Reprint-Pulavarty-OLS2003.pdf

See Also:

Ian Barile "I/O Multiplexing & Scalable Socket Servers", 2004 February, DDJ

Further reading on event handling

- http://www.cs.wustl.edu/~schmidt/ACE-papers.html

The Adaptive Communication Environment

http://www.cs.wustl.edu/~schmidt/ACE.html

Terabit Solutions

http://terabit.com.au/solutions.php

About the authors

Alex Libman has been programming for 15 years. During the past 5 years his main area of interest is pattern-oriented multiplatform networked programming using C++ and Java. He is big fan and contributor of ACE.

Vlad Gilbourd works as a computer consultant, but wishes to spend more time listening jazz :) As a hobby, he started and runs www.corporatenews.com.au website.