Studying note of GCC-3.4.6 source (142)

5.12.5.2.2.2.1.3.12. Finish the derived RECORD_TYPE – generate VTT

Virtual table table (VTT) is not mandatory for class, so build_vtt below may generate VTT or may not. Note dump_class_hierarchy below at line 5188, option –fdump-class-hierarchy will trigger the function to dump content we see in previous section.

finish_struct_1 (continue)

5174 /* Build the VTT for T. */

5175 build_vtt (t);

5176

5177 if (warn_nonvdtor && TYPE_POLYMORPHIC_P (t) && TYPE_HAS_DESTRUCTOR (t)

5178 && DECL_VINDEX (TREE_VEC_ELT (CLASSTYPE_METHOD_VEC (t), 1)) == NULL_TREE)

5179 warning ("`%#T' has virtual functions but non-virtual destructor", t);

5180

5181 complete_vars (t);

5182

5183 if (warn_overloaded_virtual )

5184 warn_hidden (t);

5185

5186 maybe_suppress_debug_info (t);

5187

5188 dump_class_hierarchy (t);

5189

5190 /* Finish debugging output for this type. */

5191 rest_of_type_compilation (t, ! LOCAL_CLASS_P (t));

5192 }

While for class contains virtual base, virtual table constructed above is not the final one. It requires virtual table table (VTT) in place of virtual table. A VTT holds:

1. primary virtual pointer for complete object of the most derived class.

2. secondary VTTs for each direct non-virtual base of the most derived class which requires a VTT.

3. secondary virtual pointers for each direct or indirect base of the most derived class which has virtual bases or is reachable via a virtual path from the most derived class.

4. secondary VTTs for each direct or indirect virtual base of the most derived class.

Secondary VTTs look like complete object VTTs without part 4.

About VTT and layout with inheritage, here is a good note, we abstract it here.

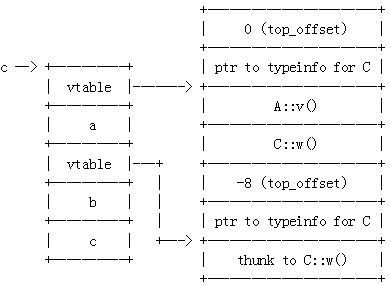

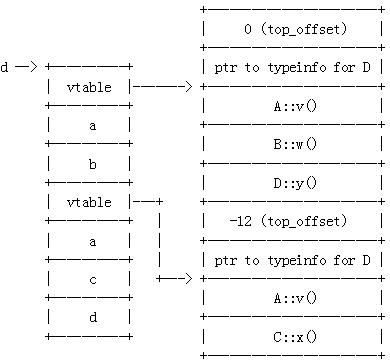

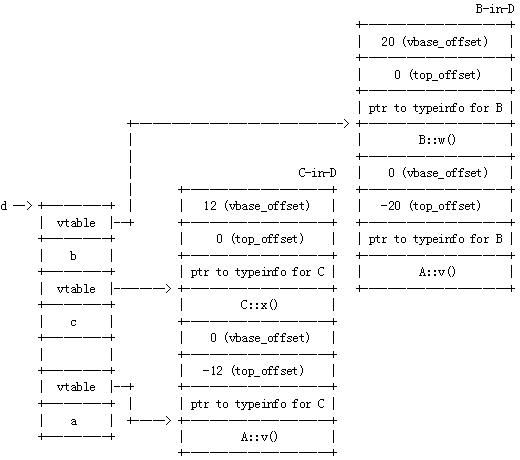

The Basics: Single InheritanceAs we discussed in class, single inheritance leads to an object layout with base class data laid out before derived class data. So if classes A and B are defined thusly: class A { public : int a; }; class B : public A { public : int b; }; then objects of type B are laid out like this (where "b" is a pointer to such an object): If you have virtual methods: class A { public : int a; virtual void v(); }; class B : public A { public : int b; }; then you'll have a vtable pointer as well: that is, top_offset and the typeinfo pointer live above the location to which the vtable pointer points. Simple Multiple InheritanceNow consider multiple inheritance: class A { public : int a; virtual void v(); }; class B { public : int b; virtual void w(); }; class C : public A, public B { public : int c; }; In this case, objects of type C are laid out like this: ...but why? Why two vtables in one? Well, think about type substitution. If I have a pointer-to-C, I can pass it to a function that expects a pointer-to-A or to a function that expects a pointer-to-B. If a function expects a pointer-to-A and I want to pass it the value of my variable c (of type pointer-to-C), I'm already set. Calls to A::v() can be made through the (first) vtable, and the called function can access the member a through the pointer I pass in the same way as it can through any pointer-to-A. However, if I pass the value of my pointer variable c to a function that expects a pointer-to-B, we also need a subobject of type B in our C to refer it to. This is why we have the second vtable pointer. We can pass the pointer value (c + 8 bytes) to the function that expects a pointer-to-B, and it's all set: it can make calls to B::w() through the (second) vtable pointer, and access the member b through the pointer we pass in the same way as it can through any pointer-to-B. Note that this "pointer-correction" needs to occur for called methods too. Class C inherits B::w() in this case. When w() is called on through a pointer-to-C, the pointer (which becomes the this pointer inside of w()) needs to be adjusted. This is often called this pointer adjustment . In some cases, the compiler will generate a thunk to fix up the address. Consider the same code as above but this time C overrides B's member function w(): class A { public : int a; virtual void v(); }; class B { public : int b; virtual void w(); }; class C : public A, public B { public : int c; void w(); }; C's object layout and vtable now look like this: Now, when w() is called on an instance of C through a pointer-to-B, the thunk is called. What does the thunk do? Let's disassemble it (here, with gdb): 0x0804860c <_ZThn8_N1C1wEv+0>: addl $0xfffffff8,0x4(%esp) 0x08048611 <_ZThn8_N1C1wEv+5>: jmp 0x804853c <_ZN1C1wEv> So it merely adjusts the this pointer and jumps to C::w(). All is well. But doesn't the above mean that B's vtable always points to this C::w() thunk? I mean, if we have a pointer-to-B that is legitimately a B (not a C), we don't want to invoke the thunk, right? Right. The above embedded vtable for B in C is special to the B-in-C case. B's regular vtable is normal and points to B::w() directly. The Diamond: Multiple Copies of Base Classes (non-virtual inheritance)Okay. Now to tackle the really hard stuff. Recall the usual problem of multiple copies of base classes when forming an inheritance diamond: class A { public : int a; virtual void v(); }; class B : public A { public : int b; virtual void w(); }; class C : public A { public : int c; virtual void x(); }; class D : public B, public C { public : int d; virtual void y(); }; Note that D inherits from both B and C, and B and C both inherit from A. This means that D has two copies of A in it. The object layout and vtable embedding is what we would expect from the previous sections: Of course, we expect A's data (the member a) to exist twice in D's object layout (and it is), and we expect A's virtual member functions to be represented twice in the vtable (and A::v() is indeed there). Okay, nothing new here. The Diamond: Single Copies of Virtual BasesBut what if we apply virtual inheritance? C++ virtual inheritance allows us to specify a diamond hierarchy but be guaranteed only one copy of virtually inherited bases. So let's write our code this way: class A { public : int a; virtual void v(); }; class B : public virtual A { public : int b; virtual void w(); }; class C : public virtual A { public : int c; virtual void x(); }; class D : public B, public C { public : int d; virtual void y(); }; All of a sudden things get a lot more complicated. If we can only have one copy of A in our representation of D, then we can no longer get away with our "trick" of embedding a C in a D (and embedding a vtable for the C part of D in D's vtable). But how can we handle the usual type substitution if we can't do this? Let's try to diagram the layout: Okay. So you see that A is now embedded in D in essentially the same way that other bases are. But it's embedded in D rather than in its directly-derived classes. Construction/Destruction in the Presence of Multiple InheritanceHow is the above object constructed in memory when the object itself is constructed? And how do we ensure that a partially-constructed object (and its vtable) are safe for constructors to operate on? Fortunately, it's all handled very carefully for us. Say we're constructing a new object of type D (through, for example, new D). First, the memory for the object is allocated in the heap and a pointer returned. D's constructor is invoked, but before doing any D-specific construction it call's A's constructor on the object (after adjusting the this pointer, of course!). A's constructor fills in the A part of the D object as if it were an instance of A. Control is returned to D's constructor, which invokes B's constructor. (Pointer adjustment isn't needed here.) When B's constructor is done, the object looks like this: But wait... B's constructor modified the A part of the object by changing it's vtable pointer! How did it know to distinguish this kind of B-in-D from a B-in-something-else (or a standalone B for that matter)? Simple. The virtual table table told it to do this. This structure, abbreviated VTT, is a table of vtables used in construction. In our case, the VTT for D looks like this:

D's constructor passes a pointer into D's VTT to B's constructor (in this case, it passes in the address of the first B-in-D entry). And, indeed, the vtable that was used for the object layout above is a special vtable used just for the construction of B-in-D. Control is returned to the D constructor, and it calls the C constructor (with a VTT address parameter pointing to the "C-in-D+12" entry). When C's constructor is done with the object it looks like this: As you see, C's constructor again modified the embedded A's vtable pointer. The embedded C and A objects are now using the special construction C-in-D vtable, and the embedded B object is using the special construction B-in-D vtable. Finally, D's constructor finishes the job and we end up with the same diagram as before: Destruction occurs in the same fashion but in reverse. D's destructor is invoked. After the user's destruction code runs, the destructor calls C's destructor and directs it to use the relevant portion of D's VTT. C's destructor manipulates the vtable pointers in the same way it did during construction; that is, the relevant vtable pointers now point into the C-in-D construction vtable. Then it runs the user's destruction code for C and returns control to D's destructor, which next invokes B's destructor with a reference into D's VTT. B's destructor sets up the relevant portions of the object to refer into the B-in-D construction vtable. It runs the user's destruction code for B and returns control to D's destructor, which finally invokes A's destructor. A's destructor changes the vtable for the A portion of the object to refer into the vtable for A. Finally, control returns to D's destructor and destruction of the object is complete. The memory once used by the object is returned to the system. Now, in fact, the story is somewhat more complicated. Have you ever seen those "in-charge" and "not-in-charge" constructor and destructor specifications in GCC-produced warning and error messages or in GCC-produced binaries? Well, the fact is that there can be two constructor implementations and up to three destructor implementations. An "in-charge" (or complete object ) constructor is one that constructs virtual bases, and a "not-in-charge" (or base object ) constructor is one that does not. Consider our above example. If a B is constructed, its constructor needs to call A's constructor to construct it. Similarly, C's constructor needs to construct A. However, if B and C are constructed as part of a construction of a D, their constructors should not construct A, because A is a virtual base and D's constructor will take care of constructing it exactly once for the instance of D. Consider the cases: · If you do a new A, A's "in-charge" constructor is invoked to construct A. · When you do a new B, B's "in-charge" constructor is invoked. It will call the "not-in-charge" constructor for A. · new C is similar to new B. · A new D invokes D's "in-charge" constructor. We walked through this example. D's "in-charge" constructor calls the "not-in-charge" versions of A's, B's, and C's constructors (in that order). An "in-charge" destructor is the analogue of an "in-charge" constructor---it takes charge of destructing virtual bases. Similarly, a "not-in-charge" destructor is generated. But there's a third one as well. An "in-charge deleting" destructor is one that deallocates the storage as well as destructing the object. So when is one called in preference to the other? Well, there are two kinds of objects that can be destructed---those allocated on the stack, and those allocated in the heap. Consider this code (given our diamond hierarchy with virtual-inheritance from before): D d; // allocates a D on the stack and constructs it D *pd = new D; // allocates a D in the heap and constructs it /* ... */ delete pd; // calls "in-charge deleting" destructor for D return ; // calls "in-charge" destructor for stack-allocated D We see that the actual delete operator isn't invoked by the code doing the delete, but rather by the in-charge deleting destructor for the object being deleted. Why do it this way? Why not have the caller call the in-charge destructor, then delete the object? Then you'd have only two copies of destructor implementations instead of three... Well, the compiler could do such a thing, but it would be more complicated for other reasons. Consider this code (assuming a virtual destructor, which you always use, right?...right?!? ): D *pd = new D; // allocates a D in the heap and constructs it C *pc = d; // we have a pointer-to-C that points to our heap-allocated D /* ... */ delete pc; // call destructor thunk through vtable, but what about delete? If you didn't have an "in-charge deleting" variety of D's destructor, then the delete operation would need to adjust the pointer just like the destructor thunk does. Remember, the C object is embedded in a D, and so our pointer-to-C above is adjusted to point into the middle of our D object. We can't just delete this pointer, since it isn't the pointer that was returned by malloc() when we constructed it. So, if we didn't have an in-charge deleting destructor, we'd have to have thunks to the delete operator (and represent them in our vtables), or something else similar. Multiple Inheritance with Virtual Methods on One SideOkay. One last exercise. What if we have a diamond inheritance hierarchy with virtual inheritance, as before, but only have virtual methods along one side of it? So: class A { public : int a; }; class B : public virtual A { public : int b; virtual void w(); }; class C : public virtual A { public : int c; }; class D : public B, public C { public : int d; virtual void y(); }; In this case the object layout is the following: So you can see the C subobject, which has no virtual methods, still has a vtable (albeit empty). Indeed, all instances of C have an empty vtable.

|