本篇分享包含三个部分:

《一、林德散文《无知常乐》英文版赏析》:直接欣赏原文。

《二、赏析参考译文》:直接欣赏优美的译文。

《三、自译和参考译文比对》:比对自译和参考译文进行翻译学习。

一、林德散文《无知常乐》英文版赏析

The Pleasures of Ignorance

Robert Lynd

If I have called in the cuckoo to illustrate the ordinary man's ignorance, it is not because I can speak with authority on that bird. It is simply because, passing the spring in a parish that seemed to have been invaded by all the cuckoos of Africa, I realized how exceedingly little I, or anybody else I met, knew about them. But your and my ignorance is not confined to cuckoos. It dabbles in all created things, from the sun and moon down to the names of the flowers. I once heard a clever lady asking whether the new moon always appears on the same day of the week. She added that perhaps it is better not to know, because, if one does not know when or in what part of the sky to expect it, its appearance is always a pleasant surprise. I fancy, however, the new moon always comes as a surprise even to those who are familiar with her time-tables. And it is the same with the coming-in of spring and the waves of the flowers. We are not the less delighted to find an early primrose because we are sufficiently learned in the services of the year to look for it in March or April rather than in October. We know, again, that the blossom precedes and not succeeds the fruit of the apple-tree, but this does not lessen our amazement at the beautiful holiday of a May orchard.

At the same time there is, perhaps, a special pleasure in re-learning the names of many of the flowers every spring. It is like re-reading a book that one has almost forgotten. Montaigne tell us that he had to bad a memory that he could always read an old book as though he had never read it before. I have myself a capricious and leaking memory. I can read Hamlet itself and The pickwick Papers as though they were the work of new authors and had come wet from the press, so much of them fades between one reading and another. There are occasions on which a memory of this kind is an affliction, especially if one has a passion or accuracy. But this is only when life has an object beyond entertainment. In respect of mere luxury, it may be doubted whether there is now as much to be said for a bad memory as for a good one. With a bad memory one can go on reading Plutarch and The Arabian Nights all one's life. Little shreds and tags, it is probable, will stick even in the worst memory, just as a succession of sheep cannot leap through a gap in a hedge without leaving a few wisps of wool on the thorns. But the sheep themselves escape, and the great authors leap in the same way out of an idle memory and leave little enough behind.

And, if we can forget books, it is as easy to forget the months and what they showed us, when once they are gone. Just for a moment I tell myself that I know May like the multiplication table and could pass an examination on its flowers. their appearance and their order. Today I can affirm confidently that the buttercup has five petals.(Or is it six? I knew for certain last week.) But next year I shall probably have forgotten my arithmetic, and may have to learn once more not to confuse the buttercup with the celandine. Once more I shall see the world as a garden through the eyes of a stranger, my breath taken away with surprise by the painted fields. I shall find myself wondering whether it is science or ignorance which affirms that the swift(that black exaggeration of the swallow and yet a kinsman of the humming-bird) never settles even on a nest, but disappears at night into the heights of the air. I shall learn with fresh astonishment that it is the male, and not the female, cuckoo that sings. I may have to learn again not to call the campion a wild geranium, and to rediscover whether the ash comes early or late in the etiquette of the trees. A contemporary English novelist was once asked by a foreigner what was the most important crop in England. He answered without a moment's hesitation, "Rye." Ignorance so complete as this seems to me to be touched with magnificence; but the ignorance even of illiterate persons is enormous. The average man who uses a telephone could not explain how a telephone works. He takes for granted the miracles of the gospels. He neither questions nor understands them. It is as though each of us investigated and make his own only a tiny circle of facts. Knowledge outside the day's work is regarded by most men as a gewgaw. Still we are constantly in reaction against our ignorance. We rouse ourselves at intervals and speculate. We revel in speculations about anything at all - about life after death or about such questions as that which is said to have puzzled Aristotle, "why sneezing from noon to midnight was good, but from night to noon unlucky." One of the greatest joys known to man is to take such a flight into ignorance in search of knowledge. The great pleasure of ignorance is, after all, the pleasure of asking questions. The man who has lost this pleasure or exchanged it for the pleasure of dogma, which is the pleasure of answering, is already beginning to stiffen. One envies so inquisitive a man as Joweet, who sat down to the study of physiology in his sixties. Most of us have lost the sense of our ignorance long before that age. We even become vain of our squirrel's hoard of knowledge and regard increasing age itself as a school of omniscience. We forget that Socrates was famed for wisdom not because he was omniscient but because he realized at the age of 70 that he still knew nothing.

二、参考译文赏析

无知常乐

罗伯特﹒林德

我请杜鹃来做例子以说明普通人的无知,并不是因为我有什么权威对这种鸟儿发发议论。不过, 我曾在某个教区暂住,而那天春天从非洲飞来的杜鹃似乎全集合在那个地方,因此我也就有了机会了解到我自己以及我所碰见的每一个人对这种鸟儿的知识是如何地微不足道。但是,你我的无知并不限于杜鹃这一方面。它涉及到宇宙万物,从太阳、月亮一直到花卉的名字。有一天,我听见一位聪明伶俐的太太提出了这样一个问题:新月是不是总在星期几露面?她接着又说:不知道倒好,正因为人不知道在什么时候、在天空的哪一带能看见它,新月一出现才给人带来一场惊喜。然而我想,哪怕人把月亮盈亏时间表记得再熟,看见新月出现还是不免又惊又喜,春回大地,花开花落,也莫不如此。尽管我们对一年四季草木节令了如指掌,知道樱草开花在三月或四月而不在十月,不过看见一株早开花的樱草,我们还是照样地高兴。另外,我们知道苹果树先开花,后结果,可是五月一旦到来,果园里一片欢闹的花海,我们不是仍然惊为奇观吗?

倘在每年春天,把许多花卉之名重温一遍,还另有一番风味。那就像把一本差不多忘得干干净净的书再重新念一遍。蒙田说过,他的记忆力很坏,所以他随时都能拿起一本旧书,像从未读过的新书一样地念。我自己的记忆力也漏洞百出、不听使唤。我甚至能拿起《哈姆雷特》和《匹克威克外传》,当作是初登文坛的新作家刚刚印成白纸黑字的作品来念,因为自从上回念过以后,这两部书在我脑子里的印象已经模模糊糊了。这样的记忆力,在某些场合自然叫人伤脑筋,尤其当人渴望精确的时候。不过,在这种时候,人不仅想得到娱乐,还追求着什么目的。如果只讲享受的话,记忆力坏比记忆力好究竟差到哪里去,还真是大可怀疑呢。记忆力坏的人可以一辈子不断地念普卢塔克的《英雄传》和《天方夜谭》,而永远从篱笆洞里连接通过,总不免在那刺条上留下一丝半缕的羊毛。然而,绵羊终归逃出去了,正像伟大的作家从我们不争气的记忆中消失,所留下的东西简直微不足道。

既然读过的书我们可以忘得一干二净,那么一年十二个月以及每个月的风物,一旦时过境迁,我们同样可以轻而易举把它们忘在脑后。在某个短暂的时刻,我们可以说自己对于五月就像对于乘法表那样熟悉。关于五月里的花木、开花时间乃至前后次序,我能通过考试。今天,我就敢肯定金凤花有五瓣。(难道是六瓣吗?上个礼拜我还记得清清楚楚来者。)可是,到了明年,我也许连算术也忘了个干干净净;我得从头学起,以免把金凤花误认为白屈菜。那时,我像一个陌生人进入大花园,放眼四望,五色缤纷的原野再一次使我目不暇接,心迷神醉。那时,我也许要对这么一个问题拿不定主意,就是:认为雨燕(那种简直像大号小燕子,又和蜂鸟沾点儿亲戚的黑鸟儿)从来不在巢里歇着,一到夜里就飞向高高的天空,到底是一种科学论断,还是一种无知妄说? 当我知道了会唱歌的并不是雌杜鹃,而是雄杜鹃,我还要再次感到惊讶。我得重新学习,以免把剪秋罗当作野天竺葵;还要去重新发现白杨在树木生长中习惯上究竟算是早成材还是晚成材。某天,一个外国人问一位当代英国小说家,英国最重要的农作物是什么。他毫不犹豫地回答:“黑麦。” 在我看来,这是一种堂而皇之的彻头彻尾的无知;不过,大大的无知也包括那些没有文化的人。普通人只会使用电话,却无法解释电话的工作原理。他把电话、火车、铸造排字机、飞机都看作当然之事,就像我们的祖父一代把《福音》书里的奇迹故事视为理所当然一样。对于这些事,他既不去怀疑,也不去了解。我们每个人似乎只对很小范围内的某几件事才真正下工夫去了解、弄清楚。大部分人把日常工作以外的一切知识统统当作花哨无用的玩意儿。然而,对于我们的无知,我们还是时时抗拒着,我们有时振作起来,进行思索。我们随便找一个题目,对之思考,甚至入迷——关于死后的生命,或者关于某些据说亚里士多德也感到大惑不解的问题,例如“打喷嚏,从中午到子夜为吉,从夜晚至中午 则凶,其故安在?”为求知而陷入无知,这是人类所欣赏的最大乐事之一。归根结底,无知的极大乐趣即在于提出问题。一个人,如果失去了这种提问的乐趣,或者把它换成了教条的答案,并且以此为乐,那么,他的头脑已经开始僵化了。我们羡慕像裘伊特这样勤学好问之人,他到了60多岁居然还能做下来研究生理学。我们多数人不到他这么大的岁数就早已丧失了自己无知的感觉了。我们甚至像松鼠似的对自己小小的知识存储感到沾沾自喜,把与日俱增的年龄看作是培养无所不知的天然学堂。我们忘记了:苏格拉底之所以名垂后世,并非因为他无所不知,而是因为他到了70高龄还能明白自己仍然一无所知。

三、自译和参考译文比对

The Pleasures of Ignorance

无知的快乐

Robert Lynd

If I have called in the cuckoo to illustrate the ordinary man's ignorance, it is not because I can speak with authority on that bird. It is simply because, passing the spring in a parish that seemed to have been invaded by all the cuckoos of Africa, I realized how exceedingly little I, or anybody else I met, knew about them.

[自译练习]:如果我谈起杜鹃的话题,来说明普通人的无知,那并不是因为我能以权威的谈资来讨论那种鸟。这仅仅是因为,当我在一个似乎被非洲所有的杜鹃侵扰的教区里度过春天时,我意识到,无论是我自己,还是我遇到的任何人,对这些鸟的了解都是如此之少。

[参考译文]:我请杜鹃来做例子以说明普通人的无知,并不是因为我有什么权威对这种鸟儿发发议论。不过, 我曾在某个教区暂住,而那天春天从非洲飞来的杜鹃似乎全集合在那个地方,因此我也就有了机会了解到我自己以及我所碰见的每一个人对这种鸟儿的知识是如何地微不足道。

“call in ”是英语成语,作“请来,约请”解时,后接“某人”作宾语。如:“Grandma was so ill that she was unable to move. We had to call in a doctor.”奶奶病得很重,又不能动弹,我们只得请医生来。此句中,作者“请杜鹃来做例子”是用了拟人化手法,不仅行文生动,也体现了作者对花草鸟虫和大自然的热爱。

But your and my ignorance is not confined to cuckoos. It dabbles in all created things, from the sun and moon down to the names of the flowers. I once heard a clever lady asking whether the new moon always appears on the same day of the week. She added that perhaps it is better not to know, because, if one does not know when or in what part of the sky to expect it, its appearance is always a pleasant surprise.

[自译练习]:但是你我的无知并不局限于杜鹃鸟,而是涉及大自然的一切造物,从太阳和月亮到花卉的名字。我曾经听说有一位聪明的女士问及新月是否总是在那一周的同一天出现。她补充说还是不要知道更好,因为,如果一个人不知道新月什么时间在天空的什么部分出现,它的外观就会一直让人感到惊奇和愉悦。

[参考译文]: 但是,你我的无知并不限于杜鹃这一方面。它涉及到宇宙万物,从太阳、月亮一直到花卉的名字。有一天,我听见一位聪明伶俐的太太提出了这样一个问题:新月是不是总在星期几露面?她接着又说:不知道倒好,正因为人不知道在什么时候、在天空的哪一带能看见它,新月一出现才给人带来一场惊喜。

不得不说参考译文还是更高明,例如"The same day of the week"直译确实是"一周里面的同一天”,这个意思,进行语言脱壳之后,不就是“星期几”嘛!何必译作“一周的同一天”?

I fancy, however, the new moon always comes as a surprise even to those who are familiar with her time-tables. And it is the same with the coming-in of spring and the waves of the flowers. We are not the less delighted to find an early primrose because we are sufficiently learned in the services of the year to look for it in March or April rather than in October. We know, again, that the blossom precedes and not succeeds the fruit of the apple-tree, but this does not lessen our amazement at the beautiful holiday of a May orchard.

[自译练习]:然而我喜欢说,对于熟悉新月时间表的人来说,新月还是一直会带来惊喜。这对于春季的到来和如潮的花卉也是如此。我们并不会因为我们已经熟知报春花在一年中的花期是在三四月而不是十月,就会减少当我们发现提前开放的报春花时的欣喜。我们也知道苹果树是先开花再结果,但这并不会减少我们在五月的苹果园度过美好假日的乐趣。

[参考译文]:然而我想,哪怕人把月亮盈亏时间表记得再熟,看见新月出现还是不免又惊又喜,春回大地,花开花落,也莫不如此。尽管我们对一年四季草木节令了如指掌,知道樱草开花在三月或四月而不在十月,不过看见一株早开花的樱草,我们还是照样地高兴。另外,我们知道苹果树先开花,后结果,可是五月一旦到来,果园里一片欢闹的花海,我们不是仍然惊为奇观吗?

“in the services of the year”中的每个词我们都再熟悉不过,但当services与year搭配,表示自然界的现象,且用在本文中时,它就不再表示“服务”、“帮忙”、“公共设施”等意义。大自然母亲一年四季在不同的时刻为我们人类奉献不同的花木果实,为大地点染不同的色彩。所以,译者将“services of the year”引申为“一年四季草木节令”。(以上来自英语笔译实务教材中的注释讲解)。

吴和平:对比自己的自译练习和参考译文:

一、我把“her time-tables”译为“新月时间表”,这就是直译,但是参考译文用了补译:“月亮盈亏时间表”,补了“盈亏”二字,更加符合中文的表达习惯。

二、“Coming-in of spring and the waves of the flowers.”被参考译文译作“春回大地,花开花落”,是不是过于意译了?原文只是指春天来了的时候,花卉像waves(波浪、浪潮)一样,哪儿来的“花开花落”里面的花落呢?并不是在说四个季节,而是只在说春季啊。

三、参考译文“另外,我们知道苹果树先开花,后结果,可是五月一旦到来,果园里一片欢闹的花海,我们不是仍然惊为奇观吗?”,朗读起来确实琅琅上口,比我自己翻译的句子“我们也知道苹果树是先开花再结果,但这并不会减少我们在五月的苹果园度过美好假日的乐趣。”读起来更符合中文表达,我的翻译的问题是这个句子太长,基本上是按照原文直译,而参考译文的优点是将英文原文过长的句子切割,以“大珠小珠落玉盘”的节奏表达出来 。只是不知道“欢闹”二字,是否是有些过份发挥想象了,此点不敢苟同。整体而言,参考译文还是非常赏心悦目、琅琅上口的!

At the same time there is, perhaps, a special pleasure in re-learning the names of many of the flowers every spring. It is like re-reading a book that one has almost forgotten. Montaigne tell us that he had so bad a memory that he could always read an old book as though he had never read it before.

[自译练习]:与此同时,也许,在每个春天重新学习一遍各种花卉的名字是一种特别的乐趣。这就像重新阅读一本已经忘得差不多的书一样。蒙特奇(Montaigne)告诉我们,他的记忆力是如此的糟糕,以至于他能经常读一本旧书读得津津有味就像以前从来没有读过它一样。

[参考译文]:倘在每年春天,把许多花卉之名重温一遍,还另有一番风味。那就像把一本差不多忘得干干净净的书再重新念一遍。蒙田说过,他的记忆力很坏,所以他随时都能拿起一本旧书,像从未读过的新书一样地念。

蒙田(Montaigne)是16世纪法国思想家和作家。20世纪以来,他被公认为伟大的作家,大多数读者视他为良师益友和随笔巨匠。(以上来自英语笔译实务教材中的注释讲解)。

吴和平:自我批评下,把Montaigne这个名字译作“蒙特奇”或者"蒙太奇",是贻笑大方了,常见的著名人物,已经有公认的中文名,翻译的时候应该沿用,不能自己乱翻!比如“常凯申”这个中文名字,已经成为段子。

I have myself a capricious and leaking memory. I can read Hamlet itself and The pickwick Papers as though they were the work of new authors and had come wet from the press, so much of them fades between one reading and another.

[自译练习]:我自己也有着变化莫测和漏洞百出的记忆力。我能读起《哈姆雷特》和《匹克威克外传》来读得就像它们是新作家刚出版的作品似的,在某一次阅读和另一次阅读中,忘记了太多的内容。

[参考译文]:我自己的记忆力也漏洞百出、不听使唤。我甚至能拿起《哈姆雷特》和《匹克威克外传》,当作是初登文坛的新作家刚刚印成白纸黑字的作品来念,因为自从上回念过以后,这两部书在我脑子里的印象已经模模糊糊了。

capricious是形容词,正式用语,意为“(态度或行为)反复无常的,变幻莫测的,任性的”。它修饰memory,若直接套用词典上的译文,则不忍卒读。想一想,怎样才合适?(以上来自英语笔译实务教材中的注释讲解)。

吴和平:意思就是在本段中,capricious译作“不听使唤”呗!变幻莫测的记忆,意思就是主人无法控制自己的记忆了,意思就是“不听使唤”。是的,脱壳!学翻译,要对源语言描述的内容理解透彻,然后脱壳!

There are occasions on which a memory of this kind is an affliction, especially if one has a passion or accuracy. But this is only when life has an object beyond entertainment. In respect of mere luxury, it may be doubted whether there is now as much to be said for a bad memory as for a good one.

[自译练习]:有的情况下如此糟糕的记忆确实是一种折磨,特别是对热衷于精确性的人来说更是如此。但是,只能是当生活是有目的而不是娱乐才能这么这么认为。仅仅就奢侈地享受阅读来说,糟糕的记忆也许并不是一件坏事了。

[参考译文]:这样的记忆力,在某些场合自然叫人伤脑筋,尤其当人渴望精确的时候。不过,在这种时候,人不仅想得到娱乐,还追求着什么目的。如果只讲享受的话,记忆力坏比记忆力好究竟差到哪里去,还真是大可怀疑呢。

affliction此处为可数名词,正式用语,意为“造成痛苦的事物”(来自英语笔译实务教材中的注释讲解)。

With a bad memory one can go on reading Plutarch and The Arabian Nights all one's life. Little shreds and tags, it is probable, will stick even in the worst memory, just as a succession of sheep cannot leap through a gap in a hedge without leaving a few wisps of wool on the thorns. But the sheep themselves escape, and the great authors leap in the same way out of an idle memory and leave little enough behind.

[自译练习]: 记忆力不好的人可以一辈子都读普罗塔克和《天方夜谭》。即使在最糟糕的记忆中,小碎片和标签也很可能粘在一起,就像一群绵羊跳过树篱笆的缝隙,在荆棘上留下几缕羊毛一样。 但是绵羊自己逃脱了,伟大的作家们也是以同样的方式从你闲置的记忆中逃逸掉了,留下来的东西很少。

[参考译文]:记忆力坏的人可以一辈子不断地念普卢塔克的《英雄传》和《天方夜谭》,而永远从篱笆洞里连接通过,总不免在那刺条上留下一丝半缕的羊毛。然而,绵羊终归逃出去了,正像伟大的作家从我们不争气的记忆中消失,所留下的东西简直微不足道。

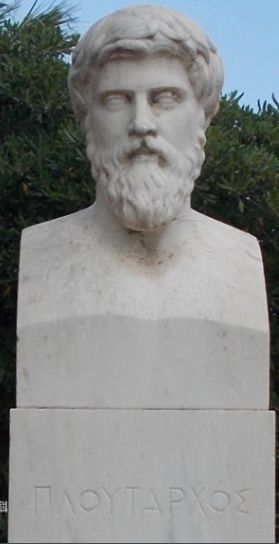

普卢塔克(Plutarch)是16世纪至19世纪初对欧洲影响最大的作家之一,一生创作了多达227中文学作品,其中最著名的是他给希腊罗马的军人、立法者、演说家和政治家撰写的《希腊罗马名人比较列传》。(以上来自英语笔译实务教材中的注释讲解)。

leap是个常用词,意为“jump vigorously”或"move suddenly and quickly"。(以上来自英语笔译实务教材中的注释讲解)。

And, if we can forget books, it is as easy to forget the months and what they showed us, when once they are gone. Just for a moment I tell myself that I know May like the multiplication table and could pass an examination on its flowers. their appearance and their order. Today I can affirm confidently that the buttercup has five petals.(Or is it six? I knew for certain last week.) But next year I shall probably have forgotten my arithmetic, and may have to learn once more not to confuse the buttercup with the celandine.

[自译练习]:我们度过的岁月及其相关一切都会逝去。如果我们能忘记读过的书,那就像忘记岁月一样容易。只是一刹那间,我告诉自己,我对五月花的掌握程度就像乘法口诀表一样熟悉,以至于可以通过一场关于这个季节的花卉的考试。它们的外观以及开放的次序。如今,我能自信地肯定毛茛有五朵花瓣。(或者是六朵?上周我还非常确信答案)但是来年,我很可能就忘记算术了,而且也许不得不再次学习,如何才能不把毛茛和白屈菜搞混。

[参考译文]:既然读过的书我们可以忘得一干二净,那么一年十二个月以及每个月的风物,一旦时过境迁,我们同样可以轻而易举把它们忘在脑后。在某个短暂的时刻,我们可以说自己对于五月就像对于乘法表那样熟悉。关于五月里的花木、开花时间乃至前后次序,我能通过考试。今天,我就敢肯定金凤花有五瓣。(难道是六瓣吗?上个礼拜我还记得清清楚楚来者。)可是,到了明年,我也许连算术也忘了个干干净净;我得从头学起,以免把金凤花误认为白屈菜。

"for a moment"与" for the moment"仅一词之差,意义迥然不同。“for a moment”意为“for a little while”,一会儿;“for the moment”意为“for now”,此刻,目前,暂时,表示“something is true now, even if it will not be true later or in the future”。参考例句:Please wait for a moment, I'm coming over.(请等我一下,我马上过来。)(以上来自英语笔译实务教材中的注释讲解)。

Once more I shall see the world as a garden through the eyes of a stranger, my breath taken away with surprise by the painted fields. I shall find myself wondering whether it is science or ignorance which affirms that the swift(that black exaggeration of the swallow and yet a kinsman of the humming-bird) never settles even on a nest, but disappears at night into the heights of the air. I shall learn with fresh astonishment that it is the male, and not the female, cuckoo that sings. I may have to learn again not to call the campion a wild geranium, and to rediscover whether the ash comes early or late in the etiquette of the trees.

[自译练习]:我将再一次从一个陌生人的视角,把世界看待成一个花园。美丽如画的田野让我为之惊奇,呼吸停滞。我将发现自己在想,究竟是科学还是无知证实了雨燕(一种鸟,黑色的羽毛有燕子那么夸张,但它却是蜂鸟的近亲)甚至从未在鸟巢上安顿下来,而是在夜里消失在高空中。我将带着全新的惊奇得知,杜鹃的歌唱来自雄性,而不是雌性。我可能不得不再次学习,不能把这种坎皮农叫做野生天竺葵,以及重新发现,白杨在树木中,算是早成材的还是晚成材的。

[参考译文]:那时,我像一个陌生人进入大花园,放眼四望,五色缤纷的原野再一次使我目不暇接,心迷神醉。那时,我也许要对这么一个问题拿不定主意,就是:认为雨燕(那种简直像大号小燕子,又和蜂鸟沾点儿亲戚的黑鸟儿)从来不在巢里歇着,一到夜里就飞向高高的天空,到底是一种科学论断,还是一种无知妄说? 当我知道了会唱歌的并不是雌杜鹃,而是雄杜鹃,我还要再次感到惊讶。我得重新学习,以免把剪秋罗当作野天竺葵;还要去重新发现白杨在树木生长中习惯上究竟算是早成材还是晚成材。

swift是“雨燕”,与燕(swallow)十分近似,翅特长,呈镰刀状,身体结实有力。humming-bird是“蜂鸟”,常与雨燕一起列入雨燕目,也可以列为蜂鸟目。括号内的文字体现了作者诙谐幽默的风格,显然不能译为“黑色的,夸张地燕,而又是蜂鸟的亲属”(以上来自英语笔译实务教材中的注释讲解)。

通常etiquette的释义是“礼仪、礼节”或“行规,成规”。(Etiquette is a set of customs and rules for polite behavior, especially among a particular class of people, or in a particular profession.)那么“the etiquette of the trees”应该怎样翻译才自然呢?(以上来自英语笔译实务教材中的注释讲解)。

A contemporary English novelist was once asked by a foreigner what was the most important crop in England. He answered without a moment's hesitation, "Rye." Ignorance so complete as this seems to me to be touched with magnificence; but the ignorance even of illiterate persons is enormous. The average man who uses a telephone could not explain how a telephone works. He takes for granted the telephone, the railway train, the linotype, the aeroplane, as our grandfathers took for granted the miracles of the gospels. He neither questions nor understands them. It is as though each of us investigated and make his own only a tiny circle of facts.

[自译练习]:一位当代的英语小说家曾经问一个外国人什么是英格兰最重要的庄稼。这位小说家毫不犹豫地回答:“黑麦”。这是如此彻底的无知,这种阔绰感动了我。 但不识字的人也有巨大的无知。使用电话的普通人不能解释电话是如何工作的。他把电话、铁路火车、铸造排字机、飞机都看作当然之事,就象我们的祖父一代把福音书里的奇迹故事视为理所当然一样。他既提不出问题也无法理解这些事物。这就好像我们中每个人都独自调查得出只属于自己的微小范围内的事实。

[参考译文]:某天,一个外国人问一位当代英国小说家,英国最重要的农作物是什么。他毫不犹豫地回答:“黑麦。” 在我看来,这是一种堂而皇之的彻头彻尾的无知;不过,大大的无知也包括那些没有文化的人。普通人只会使用电话,却无法解释电话的工作原理。他把电话、火车、铸造排字机、飞机都看作当然之事,就像我们的祖父一代把《福音》书里的奇迹故事视为理所当然一样。对于这些事,他既不去怀疑,也不去了解。我们每个人似乎只对很小范围内的某几件事才真正下工夫去了解、弄清楚。

英格兰的主要农作物应该是小麦。rye是黑麦。

“an average person”不能按字面译为“典型的人(或物)”或“正常的人(或物)”,应译为“普通人”。(来自英语笔译实务教材中的注释讲解)。

Knowledge outside the day's work is regarded by most men as a gewgaw. Still we are constantly in reaction against our ignorance. We rouse ourselves at intervals and speculate. We revel in speculations about anything at all - about life after death or about such questions as that which is said to have puzzled Aristotle, "why sneezing from noon to midnight was good, but from night to noon unlucky." One of the greatest joys known to man is to take such a flight into ignorance in search of knowledge.

[自译练习]:大部分人对自己日常工作以外的知识都视为华而不实的东西。我们实在持续性对我们的无知做出反应。我们时不时地把自己换醒,然后思索。我们沉湎于思索任何事情 —— 从死后的生活,到诸如当初让亚里士多德困惑的这些问题,“为什么从中午到半夜打喷嚏时好事,但是从晚上打喷嚏到中午不是好事呢?” 人类已知的最大乐趣之一就是为了寻求知识而陷入无知之中。

[参考译文]:大部分人把日常工作以外的一切知识统统当作花哨无用的玩意儿。然而,对于我们的无知,我们还是时时抗拒着,我们有时振作起来,进行思索。我们随便找一个题目,对之思考,甚至入迷——关于死后的生命,或者关于某些据说亚里士多德也感到大惑不解的问题,例如“打喷嚏,从中午到子夜为吉,从夜晚至中午 则凶,其故安在?”为求知而陷入无知,这是人类所欣赏的最大乐事之一。

gewgaw: 花哨(华而不实)的小玩意儿。

以上这段,是本文的主题和作者拟表达的思想。无知的快乐存在于求知的过程中,能认识到自己无知且努力将无知变有知,方能享受其中无尽的快乐。(以上引用来自英语笔译实务教材中的注释讲解)。

The great pleasure of ignorance is, after all, the pleasure of asking questions. The man who has lost this pleasure or exchanged it for the pleasure of dogma, which is the pleasure of answering, is already beginning to stiffen. One envies so inquisitive a man as Joweet, who sat down to the study of physiology in his sixties. Most of us have lost the sense of our ignorance long before that age. We even become vain of our squirrel's hoard of knowledge and regard increasing age itself as a school of omniscience. We forget that Socrates was famed for wisdom not because he was omniscient but because he realized at the age of 70 that he still knew nothing.

[自译练习]:归根结底,无知给人带来的极大乐趣是提问。失去这种乐趣的人,或者用这种提问的乐趣,来交换教条地回答问题的乐趣的人,已经开始让自己僵化了。有人羡慕一位名叫乔伊特的男人,他在六十多岁时开始做下来研究哲学。我们中的大多数人在这个年龄之前已经失去了对无知的感觉。我们甚至变得对我们自己井底之蛙的见识自命不凡,认为仅仅是年龄的增长本身,就是一所全能的大学。我们忘记了苏格拉底因智慧闻名,不是因为他是全能的,而是因为他认识到他自己到了70岁,还是一无所知。

[参考译文]: 归根结底,无知的极大乐趣即在于提出问题。一个人,如果失去了这种提问的乐趣,或者把它换成了教条的答案,并且以此为乐,那么,他的头脑已经开始僵化了。我们羡慕像裘伊特这样勤学好问之人,他到了60多岁居然还能做下来研究生理学。我们多数人不到他这么大的岁数就早已丧失了自己无知的感觉了。我们甚至像松鼠似的对自己小小的知识存储感到沾沾自喜,把与日俱增的年龄看作是培养无所不知的天然学堂。我们忘记了:苏格拉底之所以名垂后世,并非因为他无所不知,而是因为他到了70高龄还能明白自己仍然一无所知。

man可以和stiffen搭配,但译为汉语,在此语境中,不能说“人僵化”,而要说“人的思想僵化”。

Jowett 裘伊特(Benjamin Jowett,生于1817年4月15日,卒于1893年10月1日)

英国学者,古典学家和神学家。19世纪不列颠最伟大的教育家。他以译介柏拉图作品而闻名于世。生前担任过牛津大学巴利奥尔学院(Balliol College, Oxford)院长。(来自百度百科)

注意vain与hoard的词义。根据《柯斯林COBUILD英语词典》:If you describe someone as vain, you are critical of their extreme pride in their own beauty, intelligence, or other good qualities. / A hoard is a store of things that you have saved and that are valuable or important to you or you do not want other people to have. 松鼠这种小动物生活在世界各地。许多松鼠栖息在树洞或用树叶、细枝筑成的窝内,有些松鼠(如旱獭)居于地穴。松鼠主要以植物为食,特别喜食种子和坚果。由于大多数松鼠可以常年在外觅食,它们储藏在树洞或地穴中的坚果是不多的。“squirrel's hoard of knowledge”比喻知识很少。

吴和平:朋友,你觉得“squirrel's hoard of knowledge ”归化译作“井底之蛙的见识”,怎么样?