X Window系统

在你开始前

了解这些教程可以教给您什么以及如何从中获得最大收益。

关于本系列

Linux Professional Institute (LPI)在两个级别上对Linux系统管理员进行认证: 初级 (也称为“认证级别1”)和中级 (也称为“认证级别2”)。 要获得1级认证,您必须通过101和102考试; 要达到2级认证,您必须通过201和202考试。

developerWorks提供了教程,以帮助您为四门考试中的每门考试做准备。 每个考试涵盖几个主题,并且每个主题在developerWorks上都有一个相应的自学教程。 对于LPI 101考试,这五个主题和相应的developerWorks教程为:

| LPI 101考试主题 | developerWorks教程 | 教程总结 |

|---|---|---|

| 主题101 | LPI 101考试准备: 硬件和架构 |

了解如何使用Linux配置系统硬件。 在本教程结束时,您将了解Linux如何配置现代PC上的硬件,以及在遇到问题时应该去哪里寻找。 |

| 主题102 | LPI 101考试准备: Linux安装和软件包管理 |

获得有关Linux安装和软件包管理的介绍。 在本教程结束时,您将了解Linux如何使用磁盘分区,Linux如何引导以及如何安装和管理软件包。 |

| 主题103 | LPI 101考试准备: GNU和UNIX命令 |

获得有关通用GNU和UNIX命令的介绍。 在本教程结束时,您将了解如何在bash shell中使用命令,包括如何使用文本处理命令和过滤器,如何搜索文件和目录以及如何管理进程。 |

| 主题104 | LPI 101考试准备: 设备,Linux文件系统和文件系统层次结构标准。 |

了解如何在磁盘分区上创建文件系统,以及如何使用户可以访问它们,管理文件所有权和用户配额以及根据需要修复文件系统。 还了解硬链接和符号链接,以及如何在文件系统中找到文件以及应在何处放置文件。 |

| 主题110 | LPI 101考试准备: X Window系统 |

(本教程)。 了解如何安装和维护X Window系统。 请参阅下面的详细目标 。 |

要通过考试101和102(并达到1级认证),您应该能够:

- 在Linux命令行上工作

- 执行简单的维护任务:帮助用户,将用户添加到更大的系统,备份和还原以及关闭和重新启动

- 安装和配置工作站(包括X)并将其连接到LAN,或通过调制解调器将独立PC连接到Internet

要继续准备1级认证,请参阅LPI 101考试的developerWorks教程 ,以及整套developerWorks LPI教程 。

Linux Professional Institute不特别认可任何第三方考试准备材料或技术。 有关详细信息,请联系[email protected] 。

关于本教程

欢迎使用“ X窗口系统”,这是为您准备LPI 101考试而设计的五个教程中的第五个。在本教程中,您将学习有关在Linux上设置X窗口系统的信息。 本教程介绍了Linux上X的两个主要软件包:XFree86和X.Org。

本教程根据该主题的LPI目标进行组织。 粗略地说,对于体重较高的目标,应在考试中提出更多问题。

| LPI考试目标 | 客观体重 | 客观总结 |

|---|---|---|

| 1.110.1 安装和配置X |

重量5 | 配置并安装X和X字体服务器。 检查X服务器是否支持视频卡和监视器,并自定义和调整该卡和监视器的X。 安装X字体服务器,安装字体,并将X配置为使用字体服务器。 |

| 1.110.2 设置展示管理器 |

重量3 | 设置和自定义显示管理器。 打开或关闭显示管理器,并更改其问候语和默认位平面。 配置供X工作站使用的显示管理器,例如X,GNOME和KDE显示管理器。 |

| 1.110.4 安装和定制窗口管理器环境 |

重量5 | 自定义系统范围的桌面环境和窗口管理器,包括窗口管理器菜单和桌面面板菜单。 选择并配置X终端,并验证和解决X应用程序的库依赖性问题。 将X显示导出到客户端工作站。 |

先决条件

为了从本教程中获得最大收益,您应该具有Linux的基本知识以及可以在其中实践本教程中介绍的命令的Linux系统。 您还应该熟悉使用GUI应用程序,最好在X Window System下使用。

本教程以本系列前四篇教程中介绍的内容为基础,因此您可能需要首先查看主题101、102、103和104的教程 。

程序的不同版本可能会不同地格式化输出,因此您的结果可能看起来与本教程中的清单和图不完全相同。

安装和配置X

本部分介绍了初级管理(LPIC-1)考试101的主题1.110.1的材料。该主题的权重为5。

在本节中,您将学习如何:

- 检查X服务器是否支持您的视频卡和监视器

- 配置并安装X

- 自定义和调整卡和显示器的X

- 配置和安装X字体服务器

- 安装字体

X Window系统的历史

X窗口系统,也简称为X或X11,是用于图形(位图)显示的窗口系统。 X起源于1984年的MIT,是作为Athena项目的一部分开发的,该项目使用不同的硬件提供了计算环境。 X将显示功能分为显示服务器和客户端 ,它们提供应用程序逻辑。 它是网络透明的,因此显示服务器和客户端不必在同一台计算机上。 请注意,“客户端”和“服务器”的含义与您通常认为的有些相反。 除处理显示的输出外,服务器端还处理来自键盘,鼠标,图形输入板和触摸屏等设备的输入。

X提供了用于GUI应用程序的工具包,但未指定用户界面。 在典型的Linux系统上,您将在KDE或GNOME桌面之间进行选择,并且可能还有其他几个窗口管理器可用。 由于X没有指定用户界面,因此这些桌面和窗口管理器具有不同的外观。

由于X是为服务于具有不同硬件类型的大型社区而开发的,因此您会发现X客户端和服务器的不同版本通常可以很好地互操作。

XFree86和X.Org

到1987年,麻省理工学院希望移交对X的控制权,而MIT X联盟作为一个非营利组织成立,以监督X的发展。在进行了一些管理更改之后,Open Group在1999年成立了X.Org。自1992年以来,X的许多积极开发工作都是由XFree86完成的,XFree86最初为Linux所用的Intel®386硬件创建了X的端口,因此命名为XFree86。 XFree86以非付费会员的身份加入X.Org。

尽管最初是为386创建的,但XFree86的更高版本支持几种不同的平台,并且它成为Linux上使用最广泛的X版本。 在对新的许可条款和XFree86的开发模型产生争议之后,X.Org基金会成立了。 在较早的许可下使用最新的XFree86版本,它创建了X11R6.7和X11R6.8。 许多发行版仍使用XFree86,而许多发行版则改用X.Org。

视频硬件支持

XFree86和X.Org软件包都支持多种现代视频卡。 请查阅您的发行版的在线文档(请参阅参考资料 )。 某些制造商并未发布所有功能的开源驱动程序,因此您可能需要将制造商的驱动程序集成到XFree86系统中。 在制造商的网站上检查是否有改进或更新的Linux驱动程序。 对于加速的3D驱动程序,通常是这种情况。 即使XFree86无法使用卡的硬件功能,也可能可以在VESA(视频电子标准协会) 帧缓冲模式下运行。

现代监视器实现了VESA 显示数据通道 (或DDC )规范,该规范允许以编程方式确定监视器信息和功能。 XFree86配置工具( xf86config除外)使用此信息来配置X系统。

查看X如何与您的硬件一起工作的一种方法是启动实时CD发行版,例如Knoppix或Ubuntu。 这些通常具有出色的检测和使用硬件的能力。 许多发行版提供图形安装选择,这也需要正确检测和使用硬件。

XFree86

大多数发行版都包含已经为系统打包的XFree86或X.Org版本。 如果没有,您可以找到RPM或.deb软件包并根据您在本教程中针对主题102“ LPI考试101准备:Linux安装和软件包管理 ”所学的技术进行安装 。

XFree86安装

如果没有可用的XFree86软件包,则需要从XFree86项目Web站点下载文件(请参阅参考资料 )。 预构建的软件包可在几种流行的硬件平台上用于Linux,或者您可以从源代码发行版中安装。 本教程假定您将安装当前版本(版本4.5.0)的二进制软件包。

您将需要下载几个二进制软件包。 您应该使用可用的md5校验和和GPG密钥来验证下载。 表3列出了XFree86所需的文件。

| 文件 | 描述 |

|---|---|

| Xinstall.sh | 安装脚本 |

| 提取 | Tarball提取实用程序 |

| Xbin.tgz | X客户端,实用程序和运行时库 |

| Xlib.tgz | 运行时所需的数据文件 |

| Xman.tgz | 手册页 |

| Xdoc.tgz | XFree86文档 |

| Xfnts.tgz | 基本字体集 |

| Xfenc.tgz | 字体编码数据 |

| Xetc.tgz | 运行时配置文件-第1部分 |

| Xrc.tgz | 运行时配置文件-第2部分 |

| Xvar.tgz | 运行时数据 |

| Xxserv.tgz | XFree86 X服务器 |

| Xmod.tgz | X服务器模块 |

如果不确定要下载哪个版本,请下载您认为最接近的版本的Xinstall.sh文件,并使用-check选项检查系统,如清单1所示。

清单1.检查正确的XFree86二进制包

root@pinguino:~/xfree86# sh Xinstall.sh -check

Checking which OS you're running...

uname reports 'Linux' version '2.6.12-10-386', architecture 'i686'.

libc version is '6.3.5' (6.3).

Binary distribution name is 'Linux-ix86-glibc23'

If you don't find a binary distribution with this name, then

binaries for your platform are not available from XFree86.org.对于此示例,您应该查找“ Linux-ix86-glibc23”软件包。

表4列出了XFree86的可选文件。 对于本教程,您将需要字体服务器和您想要安装的任何其他项目。

| 文件 | 描述 |

|---|---|

| Xdrm.tgz | 直接渲染管理器(DRM)内核模块源 |

| Xfsrv.tgz | 字体服务器 |

| Xnest.tgz | 嵌套的X服务器 |

| Xprog.tgz | X头文件,配置文件和用于开发X应用程序的库 |

| Xprt.tgz | X打印服务器 |

| Xvfb.tgz | 虚拟帧缓冲X服务器 |

| Xtinyx.tgz | TinyX服务器 |

| Xf100.tgz | 100dpi字体 |

| Xfcyr.tgz | 西里尔字母 |

| Xfscl.tgz | 可缩放字体(Speedo,Type1和TrueType) |

| Xhtml.tgz | 文档HTML版本 |

| Xps.tgz | 文档的PostScript版本 |

| Xpdf.tgz | PDF版本的文档 |

在安装XFree86之前,应该对/ usr / X11R6,/ etc / X11和/ etc / fonts目录进行备份,因为XFree86安装可能会更改它们的内容。 您可以使用tar , cp或zip命令执行此操作。 准备安装XFree86时,请转到下载XFree86文件的目录,然后运行Xinstall.sh脚本,如清单2所示。

清单2.安装XFree86

root@pinguino:~/xfree86# sh Xinstall.sh系统将提示您回答几个问题,具体取决于您是否预先安装了X。在安装必需组件之后,将提示您分别安装可选组件。

安装文件后,该脚本将运行ldconfig命令,并为您提供一些符号链接。

安装XFree86的最简单方法是使用Xinstall.sh脚本安装所需的所有组件。 否则,您将需要重新安装整个程序包,可能会覆盖您所做的任何自定义,或者手动安装其他组件。

XFree86配置

从历史上看,配置XFree86涉及创建XF86Config文件,该文件包含有关视频卡,鼠标,键盘和显示硬件以及自定义项(如首选显示分辨率)的信息。 原始配置工具xf86config要求用户拥有并输入有关视频卡和监视器计时的详细信息。 XFree86的最新版本能够动态确定可用的硬件,并且几乎不需要配置信息就能运行。

可用的配置工具是:

- XFree86-自动配置

-

使用

-autoconfig选项运行XFree86将尝试自动配置X服务器。 如果正确确定了设置,则应该能够用鼠标在屏幕上移动X光标。 按住Ctrl和Alt键,然后按Backspace键退出显示。 这确认自动配置将起作用。 未写入配置文件。 - XFree86-配置

-

如果

-autoconfig选项不起作用,则使用-configure选项运行XFree86可能会起作用。 此选项在某些系统上也可能会引起问题。 - xf86cfg

-

xf86cfg命令尝试启动显示和输入驱动程序。 如果成功,您将看到一个带有系统图的窗口。 右键单击一个项目以查看或更新其配置。 在某些系统上,由于未正确检测到鼠标,您可能需要使用数字小键盘而不是鼠标按钮。 在运行xf86cfg之前,您可能希望尝试从实际的鼠标设备创建到/ dev / mouse的符号链接。 例如:

ln -s /dev/input/mice /dev/mouse

单击退出时 ,将提示您保存/ etc / X11R6 / lib / X11 / XF86Config和/etc/X11R6/lib/X11/xkb/X0-config.keyboard配置文件。 - xf86config

-

xf86config命令使用文本模式界面以交互方式提示您有关鼠标,键盘,视频卡和显示器的信息。 您需要显示的水平和垂直频率信息。 您可以从已知视频卡的数据库中选择大多数视频卡。 否则,您可能需要特定的芯片组和时序信息。

笔记:

- 如果您的系统包含XFree86,则您的发行商可能已包含工具,例如SUSE系统上使用的

sax2命令或某些RedHat®系统上使用的redhat-config-xfree86命令。 始终检查系统文档中有关此类工具的信息。 - 另一个配置工具

XF86Setup不再随XFree86一起分发。

X组织

大多数发行版都包含已经为系统打包的XFree86或X.Org版本。 如果没有,您可以找到RPM或.deb软件包并根据您在本教程中针对主题102“ LPI考试101准备:Linux安装和软件包管理 ”所学的技术进行安装 。

X.Org安装

如果没有可用的X.Org软件包,则需要从X.Org网站或镜像下载并构建源(请参阅参考资料 )。 在撰写本文时,这些站点不包含针对X11R6.9.0或X11R7.0的预构建二进制包。 该源可从CVS存储库中获得,也可以作为用gzip或bzip2压缩的tarball获得。 您需要获取gz或bz2文件, 而不是两者 。 在自己下载和构建X.Org时,您会发现《 X.Org模块化树开发人员指南》 (请参阅参考资料 )是非常宝贵的帮助。 请注意建议使用其他软件包,例如freetype,fontconfig和Mesa,这些软件包对于功能全面的构建建议使用。

X.Org配置

X.Org软件包基于XFree86的最新版本,并具有类似的配置功能,包括动态确定可用的硬件。 配置文件名为xorg.conf,而不是XF86Config。 您可能会在以下几个位置之一找到它:/etc/xorg.conf、/etc/X11/xorg.conf、/usr/X11R6/etc/xorg.conf、/usr/X11R6/lib/X11/xorg.conf。主机名,或/usr/X11R6/lib/X11/xorg.conf。

可用的配置工具是:

- X配置

-

使用

-configure选项运行X会导致X服务器加载每个驱动程序模块,探测该驱动程序,并创建一个配置文件,该文件保存在启动服务器的用户的主目录(通常为/ root)中。 该文件称为xorg.conf.new。 - xorgcfg

- 该工具类似于xf86cfg

- xorg86config

-

xorgconfig命令使用文本模式界面以交互方式提示您有关鼠标,键盘,视频卡和显示器的信息。 与xf86config一样,您将需要水平和垂直频率信息来进行显示。 您可以从已知视频卡的数据库中选择大多数视频卡。 否则,您可能需要特定的芯片组和时序信息。

调音X

现代的多同步CRT监视器通常具有用于设置屏幕上显示图像的大小和位置的控件。 如果您的显示器不具备此功能,则可以使用xvidtune命令调整X显示器的大小和位置。 从X终端会话运行xvidtune ,将看到一个类似于图1的窗口。调整设置并单击“ 测试”以查看其工作方式,或单击“ 应用”以更改设置。 如果单击显示 ,则当前设置将以您可以在CF86Config或xorg.conf文件中用作Modeline设置的格式打印到终端窗口。

图1.运行xvidtune

有关更多信息,请参考手册页。

X中的字体概述

多年来,X系统上的字体处理都是由核心X11字体系统完成的 。 XFree86(和X.Org)X服务器的最新版本包括Xft字体系统 。 核心字体系统最初设计为支持单色位图字体,但随着时间的流逝,它得到了增强。 Xft系统旨在满足现代要求,包括抗锯齿和亚像素光栅化,它使应用程序可以对字形的渲染进行广泛控制。 两种系统之间的主要区别在于,核心字体是在服务器上处理的,而Xft字体是由客户端处理的,客户端将必要的字形发送到服务器。

X最初使用Type 1(或Adobe Type 1)字体,这是Adobe开发的字体规范。 Xft系统可以处理这些以及OpenType,TrueType,Speedo和CID字体类型。

XFS字体服务器

使用核心X11字体系统,X Server从字体服务器获取字体和字体信息。 X字体服务器xfs通常作为守护程序运行,并在系统启动时启动,尽管可以将其作为普通任务运行。 通常,您将在X安装过程中安装字体服务器。 但是,由于X是网络协议,因此可以通过网络而不是从本地计算机获取字体和字体信息。

X字体服务器使用一个配置文件,通常为/ usr / X11R6 / lib / X11 / fs / config。 清单3中显示了样本字体配置文件。该配置文件也可以位于/ etc / X11 / fs中或链接到/ etc / X11 / fs。

清单3.示例/ usr / X11R6 / lib / X11 / fs / config

# allow a max of 10 clients to connect to this font server

client-limit = 10

# when a font server reaches its limit, start up a new one

clone-self = on

# alternate font servers for clients to use

#alternate-servers = foo:7101,bar:7102

# where to look for fonts

#

catalogue = /usr/X11R6/lib/X11/fonts/misc:unscaled,

/usr/X11R6/lib/X11/fonts/75dpi:unscaled,

/usr/X11R6/lib/X11/fonts/100dpi:unscaled,

/usr/X11R6/lib/X11/fonts/misc,

/usr/X11R6/lib/X11/fonts/Type1,

/usr/X11R6/lib/X11/fonts/Speedo,

/usr/X11R6/lib/X11/fonts/cyrillic,

/usr/X11R6/lib/X11/fonts/TTF,

/usr/share/fonts/default/Type1

# in 12 points, decipoints

default-point-size = 120

# 100 x 100 and 75 x 75

default-resolutions = 75,75,100,100

# how to log errors

use-syslog = on

# don't listen to TCP ports by default for security reasons

no-listen = tcp 此示例是Linux工作站安装的典型示例,其中字体服务器不通过TCP网络连接提供字体( no-listen = tcp )。

Xft库

Xft库提供的功能允许客户端应用程序根据模式条件选择字体并生成要发送给服务器的字形。 模式考虑了诸如字体系列(Helvetica,Times等),磅值,粗细(常规,粗体,斜体)和许多其他可能的特征等项目。 虽然核心字体系统允许客户端找到服务器上第一个可用字体的匹配项,但Xft系统会找到所有条件的最佳匹配项,然后将字形信息发送到服务器。 Xft与FreeType交互以进行字体渲染,并与X Render扩展进行交互,这有助于加快字体渲染操作。 Xft包含在XFree86和X.Org的当前版本中。

注意:如果X服务器正在网络上运行并且使用不支持X Render扩展的视频卡,则可能需要禁用抗锯齿功能,因为在这种情况下,网络性能可能会出现问题。 您可以使用xdpyinfo命令检查您的X服务器。 清单4显示了xdpyinfo部分输出。 由于xdpyinfo的输出很大,因此您可能希望使用grep过滤“ RENDER”。

清单4.使用xdpyinfo检查RENDER扩展

[ian@lyrebird ian]$ xdpyinfo

name of display: :0.0

version number: 11.0

vendor string: The XFree86 Project, Inc

vendor release number: 40300000

XFree86 version: 4.3.0

maximum request size: 4194300 bytes

motion buffer size: 256

bitmap unit, bit order, padding: 32, LSBFirst, 32

image byte order: LSBFirst

number of supported pixmap formats: 7

supported pixmap formats:

depth 1, bits_per_pixel 1, scanline_pad 32

depth 4, bits_per_pixel 8, scanline_pad 32

depth 8, bits_per_pixel 8, scanline_pad 32

depth 15, bits_per_pixel 16, scanline_pad 32

depth 16, bits_per_pixel 16, scanline_pad 32

depth 24, bits_per_pixel 32, scanline_pad 32

depth 32, bits_per_pixel 32, scanline_pad 32

keycode range: minimum 8, maximum 255

focus: window 0x2000011, revert to Parent

number of extensions: 30

BIG-REQUESTS

DOUBLE-BUFFER

DPMS

Extended-Visual-Information

FontCache

GLX

LBX

MIT-SCREEN-SAVER

MIT-SHM

MIT-SUNDRY-NONSTANDARD

RANDR

RECORD

RENDER

SECURITY

SGI-GLX

SHAPE

SYNC

TOG-CUP

X-Resource

XC-APPGROUP

XC-MISC

XFree86-Bigfont

XFree86-DGA

XFree86-DRI

XFree86-Misc

XFree86-VidModeExtension

XInputExtension

XKEYBOARD

XTEST

XVideo

default screen number: 0

number of screens: 1使用Xft代替核心X系统需要更改应用程序,因此您可能会发现某些应用程序似乎没有利用Xft更好的字体呈现功能。 在撰写本文时,Qt工具包(用于KDE)和GTK +工具包(用于GNOME)以及Mozilla 1.2及更高版本是使用Xft的应用程序的示例。

安装字体

有两种安装字体的方法,一种用于Xft,另一种用于核心X11字体。

Xft的字体

Xft使用位于一组知名字体目录中的字体,以及在用户主目录的.fonts子目录中安装的字体。 众所周知的字体目录包括/ usr / X11R6 / lib / X11 / lib / fonts的子目录,如/ usr / X11R6 / lib / X11 / fs / config中的目录条目中所列。 根据使用的X Server软件包,可以在FontPath部分XF86Config或xorg.conf中指定其他字体目录。

只需将字体文件复制到用户的.fonts目录或目录中,例如/ usr / local / share / fonts,即可在系统范围内使用。 字体服务器应选择新字体,并在下一次机会使它们可用。 您可以使用fc-cache命令触发此更新。

X中的当前字体技术使用可加载模块为不同字体类型提供字体支持,如表5所示。

| 模组 | 描述 |

|---|---|

| 位图 | 位图字体(.bdf,.pcf和.snf) |

| 自由型 | TrueType字体(.ttf和.ttc),OpenType字体(.otf和.otc)和Type 1字体(.pfa和.pfb) |

| 类型1 | 替代类型1(.pfa和.pfb)和CID字体 |

| tt | 备用TrueType模块(.ttf和.ttc) |

| 速比涛 | 比特流Speedo字体(.spd) |

如果您在安装和使用字体时遇到问题,请检查服务器日志(例如,/ var / log / XFree86.0.log),以确保已加载适当的模块。 模块名称区分大小写。 您可以使用xset命令显示(并设置)X服务器设置,包括字体路径以及配置和日志文件的位置,如清单5所示。

清单5.使用xset显示X服务器设置

[ian@lyrebird ian]$ xset -display 0:0 -q

Keyboard Control:

auto repeat: on key click percent: 0 LED mask: 00000000

auto repeat delay: 500 repeat rate: 30

auto repeating keys: 00ffffffdffffbbf

fadfffffffdfe5ff

ffffffffffffffff

ffffffffffffffff

bell percent: 50 bell pitch: 400 bell duration: 100

Pointer Control:

acceleration: 2/1 threshold: 4

Screen Saver:

prefer blanking: yes allow exposures: yes

timeout: 0 cycle: 0

Colors:

default colormap: 0x20 BlackPixel: 0 WhitePixel: 16777215

Font Path:

/home/ian/.gnome2/share/cursor-fonts,unix/:7100,/home/ian/.gnome2/share/fonts

Bug Mode: compatibility mode is disabled

DPMS (Energy Star):

Standby: 7200 Suspend: 7200 Off: 14340

DPMS is Enabled

Monitor is Off

Font cache:

hi-mark (KB): 5120 low-mark (KB): 3840 balance (%): 70

File paths:

Config file: /etc/X11/XF86Config

Modules path: /usr/X11R6/lib/modules

Log file: /var/log/XFree86.0.log如果您需要进一步控制Xft的行为,则可以使用系统范围的配置文件(/etc/fonts/fonts.conf)或特定于用户的文件(用户主目录中的.fonts.conf)。 。 您可以启用或禁用抗锯齿并控制子像素渲染(用于LCD显示器)等。 这些是XML文件,因此,如果要编辑它们,则需要确保维护格式正确的XML。 有关这些文件的内容和格式的更多信息,请查阅手册页(或信息页)中的fonts-conf。

X11核心字体

如果您具有位图分发格式(.bdf)的文件,则最好使用bdftopcf命令将它们转换为可移植编译格式(.pcf),然后在安装之前使用gzip对其进行压缩。 完成此操作后,您可以将新字体复制到目录中,例如/ usr / local / share / fonts / bitmap /,然后运行mkfontdir命令创建供字体服务器使用的字体目录。 清单6中说明了这些步骤。

清单6.安装位图字体

[root@lyrebird root]# bdftopcf courier12.bdf -o courier12.pcf

[root@lyrebird root]# gzip courier12.pcf

[root@lyrebird root]# mkdir -p /usr/local/share/fonts/bitmap

[root@lyrebird root]# cp *.pcf.gz /usr/local/share/fonts/bitmap/

[root@lyrebird root]# mkfontdir /usr/local/share/fonts/bitmap/

[root@lyrebird root]# ls /usr/local/share/fonts/bitmap/

courier12.pcf.gz fonts.dir 请注意, mkfontdir命令创建了fonts.dir文件。

安装可缩放字体(例如TrueType或Type1字体)时,需要执行额外的步骤来创建缩放信息。 将字体文件复制到目标目录后,运行mkfontscale命令,然后运行mkfontdir命令。 mkfontscale命令将在名为fonts.scale的文件中创建可缩放字体文件的索引。

一旦为新字体设置了字体目录和缩放信息,就需要通过在字体路径中包含新目录来告诉服务器在哪里可以找到它们。 您可以使用xset命令临时执行此操作,也可以通过向XF86Config或xorg.conf中添加FontPath条目来永久执行此操作。 要将新的位图字体目录添加到字体路径的前面,请使用xset的+fp选项,如清单7所示。

清单7.用xset更新fontpath

[ian@lyrebird ian]$ xset +fp /usr/local/share/fonts/bitmap/ -display 0:0 尽管此处未显示,但最好在路径中的位图字体之前添加可缩放字体,因为这样可以更好地匹配字体。 要将目录添加到路径的fp+ ,请使用fp+选项。 同样,使用-fp和fp-选项将分别从字体路径的前面和后面删除字体目录。

您可以通过编辑XF86Config或xorg.conf文件对字体路径进行永久性修改。 您可以在“文件”部分中根据需要添加任意数量的FontPath行,如清单8所示。

清单8.更新XF86Config或xorg.conf

Section "Files"

# RgbPath is the location of the RGB database. Note, this is the name of the

# file minus the extension (like ".txt" or ".db"). There is normally

# no need to change the default.

# Multiple FontPath entries are allowed (they are concatenated together)

# By default, Red Hat 6.0 and later now use a font server independent of

# the X server to render fonts.

RgbPath "/usr/X11R6/lib/X11/rgb"

FontPath "unix/:7100"

FontPath "/usr/local/share/fonts/bitmap/"

EndSection

[有关您可以对X配置文件进行的其他修改的信息,请参见XF86Config或xorg.conf的手册页(如果适用)。

设置展示管理器

本部分介绍了初中级管理(LPIC-1)考试101的主题1.110.2的材料。该主题的权重为3。

在本节中,您将学习如何:

- 设置和自定义显示管理器

- 更改显示管理员问候语

- 更改显示管理器的默认位平面

- 配置显示管理器以供X站使用

涵盖的显示管理器包括XDM(X显示管理器),GDM(GNOME显示管理器)和KDM(KDE显示管理器)。

展示经理

在上一节中,如果在尚未安装X的系统上安装并配置了X,则可能已经注意到,要获得任何类型的图形显示,必须首先登录到终端窗口并运行startx命令。 虽然这适用于本地显示,但很麻烦。 此外,它不适用于远程X终端。

解决方案是使用显示管理器显示图形登录屏幕并处理身份验证。 用户认证后,显示管理器将在运行显示管理器的系统上为该用户启动会话。 图形输出显示在用户输入其登录凭据的屏幕上。 这可以是本地显示器或通过网络连接的X显示器。

XFree86和X.Org都随XDM显示管理器一起提供。 另外两个流行的显示管理器分别是KDE和GNOME。 在本节中,您将学习如何设置和自定义这三个显示管理器。

但是,要设置图形登录,您需要了解Linux系统初始化。 您可以在即将到来的教程LPI 102考试准备(主题106):引导,初始化,关闭和运行级别以及LPI 201考试准备(主题202):系统启动中了解有关此内容的更多信息。 在本节的其余部分,您将学到足够的知识以图形登录方式启动系统,但是本节的主要重点是设置和自定义显示管理器。

在RedHat®和SUSE系统之类的系统上,X通常在运行级别5中启动。Debian系统将运行级别2到5等效,默认情况下在运行级别2中启动。默认运行级别的确定在/ etc / inittab中进行,如下所示在清单9中。

清单9.在/ etc / inittab中设置默认运行级别。

# The default runlevel is defined here

id:5:initdefault:清单10(对于SUSE系统)或清单11(对于Ubuntu系统)中的另一行确定了首先运行的脚本或程序。

清单10. SUSE(或Red Hat)系统的初始脚本

# First script to be executed, if not booting in emergency (-b) mode

si::bootwait:/etc/init.d/boot清单11. Ubuntu(或Debian)系统的初始脚本

# Boot-time system configuration/initialization script.

# This is run first except when booting in emergency (-b) mode.

si::sysinit:/etc/init.d/rcS然后,初始化脚本(/etc/init.d/boot或/etc/init.d/rcS)将运行其他脚本。 最终,将运行针对所选运行级别的一系列脚本。 对于上述示例,它们可能包括/etc/rc2.d/S13gdm(Ubuntu)或/etc/init.d/rc5.d/S16xdm(SUSE),这两个脚本都是用于运行显示管理器的脚本。 您会发现/etc/init.d中的rc n .d目录通常包含指向/etc/init.d中脚本的符号链接,而没有前导S(或K)和数字。 S表示输入运行级别时应运行脚本, K表示终止运行级别时应运行脚本。 这些数字指定运行脚本的顺序为1到99。

提示:如果要确定启动显示管理器的方式,请查找以dm结尾的脚本。

您可能会发现,用于运行显示管理器的脚本(例如/etc/init.d/rc5.d/S16xdm)可能是一个小的脚本,其中包含用于确定将实际运行哪个显示管理器的其他逻辑。 因此,尽管许多系统允许通过配置来控制它们,但您也可以通过检查初始化文件来找出将运行什么显示管理器。

可以通过在适当的rc n.d目录中创建用于启动和停止显示管理器的符号链接来控制是否在系统启动时启动显示管理器就不足为奇了。 此外,如果您需要停止或启动显示管理器,可以直接使用/etc/init.d中的脚本,如清单12所示。

清单12.停止和启动显示管理器

root@pinguino:~# /etc/init.d/gdm stop

* Stopping GNOME Display Manager... [ ok ]

root@pinguino:~# /etc/init.d/gdm start

* Starting GNOME Display Manager... [ ok ]既然您知道如何控制启动和停止显示管理器,那么让我们来看一下配置三个显示管理器中的每一个。

XDM

XFree86和X.Org软件包中包含X Display Manager(XDM)。 在文件系统层次结构标准下,配置文件应位于/ etc / X11 / xdm中。 主要配置文件是/ etc / X11 / xdm / xdm-config。 该文件包含XDM使用的其他文件的位置,有关授权要求的信息,为用户执行各种任务而运行的脚本的名称以及一些其他配置信息。

Xservers文件确定XDM应该管理哪个本地显示器。 它通常只包含一行,如清单13所示。

清单13.示例Xservers文件

:0 local /usr/X11R6/bin/X :0 vt07清单13指出X应该在虚拟终端7上运行。大多数系统支持使用Ctrl-Alt-F1至Ctrl-Alt-F7在虚拟终端之间进行切换,其中vt01至vt06是文本模式终端,而vt07是X终端。 。

如果希望支持远程X终端,则需要一个Xaccess文件。 此文件控制XDM与支持X Display Manager控制协议 ( XDCMP )的终端进行通信的方式。 Xservers文件中定义了不支持此协议的终端。 XDCMP使用众所周知的UDP端口177。出于安全原因,您应将XDCMP使用限制在具有适当防火墙保护的受信任内部网络上。

您可以通过更新/ etc / X11 / xdm中的脚本来自定义XDM的工作方式。 特别是,Xsetup(或Xsetup_0)脚本可让您自定义问候语。 图2显示了一个简单的XDM问候语,其中添加了数字时钟。

图2.修改后的XDM问候语

清单14中显示了修改后的Xsetup_0文件的源。

清单14.示例Xsetup_0文件

#!/bin/sh

xclock -geometry 80x80 -bg wheat&

xconsole -geometry 480x130-0-0 -daemon -notify -verbose -fn fixed -exitOnFail图2中显示的问候语来自使用640x480像素屏幕分辨率和256色的系统。 XDM使用XF86Config或xorg.conf文件中的默认分辨率。 要更改默认的全系统屏幕分辨率,您可以编辑此文件或使用系统附带的实用程序。 清单15显示了XF86Config文件的Screen部分。 请注意,DefaultDepth为16,因此X服务器将尝试以为此深度指定的第一个可能的分辨率(在这种情况下为1024x768)运行屏幕。

清单15.配置屏幕分辨率

Section "Screen"

DefaultDepth 16

SubSection "Display"

Depth 15

Modes "1280x1024" "1024x768" "800x600" "640x480"

EndSubSection

SubSection "Display"

Depth 16

Modes "1024x768" "800x600" "640x480"

EndSubSection

SubSection "Display"

Depth 24

Modes "1280x1024" "1024x768" "800x600" "640x480"

EndSubSection

SubSection "Display"

Depth 32

Modes "1280x1024" "1024x768" "800x600" "640x480"

EndSubSection

SubSection "Display"

Depth 8

Modes "1280x1024" "1024x768" "800x600" "640x480"

EndSubSection

Device "Device[0]"

Identifier "Screen[0]"

Monitor "Monitor[0]"

EndSection 注意Depth是指组成每个像素的位数。 您可能还会看到称为每个像素或位平面的位 。 因此,对每种颜色使用8位平面或8位最多可以允许256种颜色,而深度16时最多可以允许65536种颜色。 对于当今的图形卡,现在更常见的深度是24和32。

您可以使用带有-root选项的xwininfo命令检查屏幕分辨率,以查看正在运行的X服务器的特性,如清单16所示。

清单16.检查屏幕分辨率

ian@lyrebird:~> xwininfo -display 0:0 -root

xwininfo: Window id: 0x36 (the root window) (has no name)

Absolute upper-left X: 0

Absolute upper-left Y: 0

Relative upper-left X: 0

Relative upper-left Y: 0

Width: 1024

Height: 768

Depth: 16

Visual Class: TrueColor

Border width: 0

Class: InputOutput

Colormap: 0x20 (installed)

Bit Gravity State: NorthWestGravity

Window Gravity State: NorthWestGravity

Backing Store State: NotUseful

Save Under State: no

Map State: IsViewable

Override Redirect State: no

Corners: +0+0 -0+0 -0-0 +0-0

-geometry 1024x768+0+0KDM

KDM是K桌面环境(KDE)的K桌面管理器。 KDE版本3使用kdmrc配置文件,它是对早期版本的更改,该版本使用的基于xdm配置文件的配置信息。 它位于$ KDEDIR / share / config / kdm /目录中,其中$ KDEDIR可能是/ etc / kde3 / kdm /或其他位置。 例如,在SUSE SLES8系统上,该文件位于/ etc / opt / kde3 / share / config / kdm中。

清单17. KDM配置文件-kdmrc

[Desktop0]

BackgroundMode=VerticalGradient

Color1=205,205,205

Color2=129,129,129

MultiWallpaperMode=NoMulti

Wallpaper=UnitedLinux-background.jpeg

WallpaperMode=Scaled

[X-*-Greeter]

GreetString=UnitedLinux 1.0 (%h)

EchoMode=OneStar

HiddenUsers=nobody,

BackgroundCfg=/etc/opt/kde3/share/config/kdm/kdmrc

MinShowUID=500

SessionTypes=kde,gnome,twm,failsafe

[General]

PidFile=/var/run/kdm.pid

Xservers=/etc/opt/kde3/share/config/kdm/Xservers

[Shutdown]

HaltCmd=/sbin/halt

LiloCmd=/sbin/lilo

LiloMap=/boot/map

RebootCmd=/sbin/reboot

UseLilo=false

[X-*-Core]

Reset=/etc/X11/xdm/Xreset

Session=/etc/X11/xdm/Xsession

Setup=/opt/kde3/share/config/kdm/Xsetup

Startup=/etc/X11/xdm/Xstartup

AllowShutdown=Root

[Xdmcp]

Willing=/etc/X11/xdm/Xwilling

Xaccess=/etc/X11/xdm/Xaccess许多部分包含与XDM相同类型的配置信息,但是有一些区别。 例如,SessionTypes字段允许KDM启动几种不同会话类型中的任何一种;例如, 其他命令允许KDM关闭或重新引导系统。

您可以通过编辑kdmrc文件来配置KDM。 You can also change many of the Login Manager settings by using the KDE control center (kcontrol) as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Modifying KDM configuration with kcontrol

The KDM handbook (see Related topics ) contains extensive information on KDM configuration.

GDM

GDM is the GNOME Desktop Manager for the GNOME Desktop Environment. This desktop manager was not based on XDM, but was written from scratch. GDM uses a gdm.conf configuration file, normally located in the /etc/X11/gdm directory. Listing 18 shows part of a gdm.conf file.

Listing 18. Partial GDM configuration file - gdm.conf

# You should probably never change this value unless you have a weird setup

PidFile=/var/run/gdm.pid

# Note that a post login script is run before a PreSession script.

# It is run after the login is successful and before any setup is

# run on behalf of the user

PostLoginScriptDir=/etc/X11/gdm/PostLogin/

PreSessionScriptDir=/etc/X11/gdm/PreSession/

PostSessionScriptDir=/etc/X11/gdm/PostSession/

DisplayInitDir=/etc/X11/gdm/Init

...

# Probably should not touch the below this is the standard setup

ServAuthDir=/var/gdm

# This is our standard startup script. A bit different from a normal

# X session, but it shares a lot of stuff with that. See the provided

# default for more information.

BaseXsession=/etc/X11/xdm/Xsession

# This is a directory where .desktop files describing the sessions live

# It is really a PATH style variable since 2.4.4.2 to allow actual

# interoperability with KDM. Note that /dm/Sessions is there

# for backwards compatibility reasons with 2.4.4.x

#SessionDesktopDir=/etc/X11/sessions/:/etc/X11/dm/Sessions/:/usr/share/gdm/Buil\

tInSessions/:/usr/share/xsessions/

# This is the default .desktop session. One of the ones in SessionDesktopDir

DefaultSession=default.desktop Again, you will see some similarities in the type of configuration information used for GDM, KDM, and XDM, although gdm.conf is a much larger file with many more options.

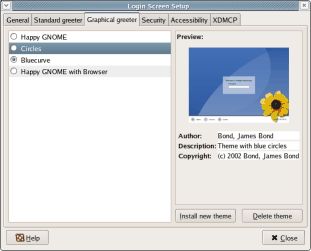

You can configure GDM by editing the gdm.conf file. You can also change many of the settings by using the gdmsetup command. Figure 4 shows an alternate graphical greeter available on a Fedora system.

Figure 4. Modifying GDM configuration with gdmsetup

The GNOME Display Manager Reference Manual (available from the gdmsetup help, or see Related topics ) contains extensive information on GDM configuration.

Customize a window manager

This section covers material for topic 1.110.4 for the Junior Level Administration (LPIC-1) exam 101. The topic has a weight of 5.

In this section, you learn how to:

- Customize a system-wide desktop environment or window manager

- Customize window manager menus and desktop panel menus

- Configure an X terminal

- Verify and resolve library dependency issues for X applications

- Export an X display

Window managers

In the previous section, you learned about display managers and how to set them up. You also learned in this tutorial that while X is a toolkit enabling applications to create graphical windows, it does not specify a user interface. In this section, you learn more about user interfaces and how to configure what happens after you have an X session up and running.

You can imagine that, without any user interface specification, developer creativity might result in many different styles of windows, all vying for space on your screen, and all with different keystrokes, mouse operations, and styles for things like buttons, dialog boxes, and so on. To bring some order to chaos, higher level toolkits were developed. These in turn gave rise to window managers , such as twm, fvwm, and fvwm2 and finally to desktops such as KDE and GNOME.

Desktops provide a consistent user experience but also consume considerable CPU and memory resources. Before computers had the power to support the likes of a KDE or GNOME desktop, window managers were popular, and many users still like them for their light weight and fast response.

If you have just installed X and you type in the command startx , then you will see a display something like Figure 5.

Figure 5. Running twm with startx

This is the twm window manager, shown with the menu that is obtained by pressing mouse button 1 (normally the left button for right-handed users) over the background. You will notice three terminal windows and an analog clock, but no task bars, launchers, or other desktop paraphernalia.

The startx command is actually a front end command to xinit , which starts the X server process and some client applications. It is usually located in /usr/X11R6/bin, as is xinit and many other X utilities. X applications can take settings from an X resources database as well as a command line. Table 6 summarizes the names and purpose of each of the configuration files used by either startx or xinit . Note that some or all of these files may not be present on a particular system or user home directory.

| 文件 | 描述 |

|---|---|

| $HOME/.xinitrc | User-defined executable script that merges in resource files and starts client applications |

| $HOME/.xserverrc | User-defined executable script that provides overrides for default X server configuration |

| /usr/X11R6/lib/X11/xinit/xinitrc | System default executable script that merges in resource files and starts client applications |

| /usr/X11R6/lib/X11/xinit/xserverrc | System default executable script that provides overrides for default X server configuration |

| $HOME/.Xresources | User-defined file describing resources for X applications |

| $HOME/.Xmodmap | User-defined file defining keyboard and mouse settings |

| /usr/X11R6/lib/X11/xinit/.Xresources | System default file describing resources for X applications |

| /usr/X11R6/lib/X11/xinit/.Xmodmap | System default file defining keyboard and mouse settings |

Note carefully that the system xinitrc and xserverrc file omit the leading dot, while all the others have it.

Every window on a screen, and indeed every widget on the screen, has attributes such as height, width, and placement (geometry), foreground and background colors or images, title text and color, and so on. For a new client application, most of these values can be supplied on the command line. Since there are many attributes, it is easier to have defaults. Such defaults are stored in a resource database , which is built from resource files using the xrdb command.

Listing 19 shows the default xinit file shipped with XFree86 4.5.0.

Listing 19. Sample xinit file - /usr/X11R6/lib/X11/xinit/xinitrc

#!/bin/sh

# $Xorg: xinitrc.cpp,v 1.3 2000/08/17 19:54:30 cpqbld Exp $

userresources=$HOME/.Xresources

usermodmap=$HOME/.Xmodmap

sysresources=/usr/X11R6/lib/X11/xinit/.Xresources

sysmodmap=/usr/X11R6/lib/X11/xinit/.Xmodmap

# merge in defaults and keymaps

if [ -f $sysresources ]; then

xrdb -merge $sysresources

fi

if [ -f $sysmodmap ]; then

xmodmap $sysmodmap

fi

if [ -f $userresources ]; then

xrdb -merge $userresources

fi

if [ -f $usermodmap ]; then

xmodmap $usermodmap

fi

# start some nice programs

twm &

xclock -geometry 50x50-1+1 &

xterm -geometry 80x50+494+51 &

xterm -geometry 80x20+494-0 &

exec xterm -geometry 80x66+0+0 -name login Note that the xrdb command is used to merge in the resources, and the xmodmap is used to update the keyboard and mouse definitions. Finally, several programs are started in the background with a final program started in the foreground using the exec command, which terminates the current script ( xinitrc ) and transfers control to the xterm window with geometry 80x66+0+0 . This is the login window, and terminating it will terminate the X server. There must be one such application, although some people prefer the window manager (twm in this example) to have this role. All other applications should be started in the background so the script can complete.

The first two values in the geometry specification define the size of the window. For a clock, this is in pixels, while for the xterm windows, it is in lines and columns. If present, the next two values define the placement of the window. If the first value is positive, the window is placed relative to the left edge of the screen, while a negative value causes placement relative to the right edge. Similarly, positive and negative second values refer to the top and bottom of the screen respectively.

Suppose you want your clock to be larger with a different colored face and to be located in the bottom right of the screen instead of the top right. If you just want this for one user, copy the above file to the user's home directory as .xinitrc (remember the dot) and edit the clock specification as shown in Listing 20. You can find all the color names in the rgb.txt file in your X installation directory tree (for example, /usr/X11R6/lib/X11/rgb.txt).

Listing 20. Modifying xclock startup in xinitrc

xclock -background mistyrose -geometry 100x100-1-1 &If you want to update the defaults for the whole installation, you should update the /usr/X11R6/lib/X11/xinit/.Xresources and /usr/X11R6/lib/X11/xinit/.Xmodmap files instead of the dot versions for individual users.

Several tools can help you customize windows and keystrokes.

- xrdb

-

Merges resources from a resource file into the X resource database for the running X server. By default it passes the source resource file through a C++ compiler. Specify the

-nocppoption if you do not have a compiler installed. - xmodmap

- Sets keyboard and mouse bindings. For example, you can switch settings for left-handed mouse usage, or set up the backspace and delete keys to work the way you are accustomed to.

- xwininfo

- Tells you information about a window, including geometry information.

- editres

- Lets you customize the resources for windows on your screen, see the changes, and save them in a file that you can later use with xrdb.

- xev

- Starts a window and captures X events that are displayed in the originating xterm window. Use this to help determine the appropriate codes to use when customizing keyboards or checking mouse events.

Use the man pages to find out more about each of these commands.

Figure 6 shows a busy screen with several of these commands running.

- The upper left terminal window (the login window) is using

xwdto capture the whole screen to a file. - The window overlapping it is running

editresto modify the resources for the clock window. - The small central window is running

xev, and the output is going to the terminal window below. The right-hand window shows the output ofxwininfofor the root window (the whole screen). - The customized clock with its face colored mistyrose is running in the bottom right corner of the screen.

Figure 6. Window information and configuration

Besides the windows themselves, the window manager also allows customization. For example, the menu that was shown in Figure 5 is configured in a twm customization file. The system default is in the X installation directory tree (/usr/X11R6/lib/X11/twm/system.twmrc), and individual users may have a .twmrc file. If a user has multiple displays, there can be files (such as .twmrc.0 or .twmrc.1) for each display number. Listing 21 shows the part of the system.twmrc file that defines the menu shown in Figure 5.

Listing 21. Menu configuration in twm

menu "defops"

{

"Twm" f.title

"Iconify" f.iconify

"Resize" f.resize

"Move" f.move

"Raise" f.raise

"Lower" f.lower

"" f.nop

"Focus" f.focus

"Unfocus" f.unfocus

"Show Iconmgr" f.showiconmgr

"Hide Iconmgr" f.hideiconmgr

"" f.nop

"Xterm" f.exec "exec xterm &"

"" f.nop

"Kill" f.destroy

"Delete" f.delete

"" f.nop

"Restart" f.restart

"Exit" f.quit

}See the man page for twm or your preferred window manager for more information.

台式机

If you are using a display manager or desktop, you will find that these also can be configured. Indeed, you already saw the Xsetup_0 file for XDM in the previous section. As with the window manager configuration that you have just seen, desktop configuration can be done system-wide or per-user.

GNOME customization

GNOME is configured mostly using XML files. System defaults are found in directories in the /etc filesystem, such as /etc/gconf, /etc/gnome, and /etc/gnome-vfs2..0, along with other directories for specific GNOME applications. User configuration is usually found in subdirectories of the home directory that start with .g. Listing 22 shows several of the possible locations for GNOME configuration information.

Listing 22. GNOME configuration locations

[ian@lyrebird ian]$ ls -d /etc/g[cn]*

/etc/gconf /etc/gnome /etc/gnome-vfs-2.0 /etc/gnome-vfs-mime-magic

[ian@lyrebird ian]$ find . -maxdepth 1 -type d -name ".g[nc]*"

./.gnome2

./.gconfd

./.gconf

./.gnome

./.gnome2_private

./.gnome-desktop

./.gnome_private Rather than extensive man pages, GNOME has an online manual; you can access the manual from the gnome-help command, or from a menu item such as Desktop > Help. As of this writing, the manual has three major sections: Desktop, Applications, and Other Documentation. The table of contents for a recent version of the Desktop Help is shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7. Window information and configuration

You will find information about configuration tools under the System Administration Guide in the Desktop section and also under the Configuration Editor Manual in the applications topic in the Desktop section.

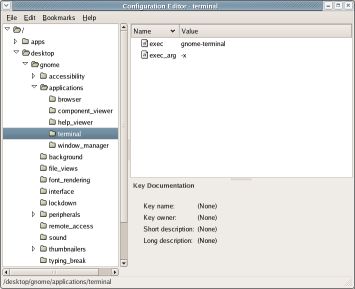

You may launch the graphical configuration editor using the gconf-editor command or by selecting Configuration Editor from the Applications > System Tools menu. The configuration for the gnome-terminal application is shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8. Window information and configuration

In addition to graphical tools, there is also a gconftool-2 command line program for interrogating and updating GNOME configuration information. See the above mentioned System Administration Guide for more details.

KDE customization

KDE is configured using plain text files with UTF-8 encoding for non-ASCII characters. As with GNOME, there may be many different configuration files. If multiple identically named files exist in different parts of the configuration tree, then the values from these are merged. Sy6stem values are located in the $KDEDIR/share/config tree, where $KDEDIR might be /etc/kde3/kdm/ or perhaps somewhere else. For example, on a SUSE SLES8 system, this is located in /etc/opt/kde3/share/config. User-specific customizations are located in the .kde/share tree in the user's home directory.

Configuration files have one or more group names enclosed in square brackets, followed by key and value pairs. The key may contain spaces and is separated from the value by an equal sign. The configuration file for the konqueror browser is shown in Listing 23.

Listing 23. KDE configuration file for konqueror browser

[HTML Settings]

[Java/JavaScript Settings]

ECMADomainSettings=localhost::Accept

JavaPath=/usr/lib/java2/jre/bin/java

EnableJava=true

EnableJavaScript=true

[EmbedSettings]

embed-text=true

embed-audio=false

embed-video=false

[Reusing]

MaxPreloadCount=1

PreloadOnStartup=trueThe configuration files may be edited manually. Most systems will include a graphical editing tool, such as KConfigEditor or a tool customized for the distribution, such as the SUSE Control Center.

Different xterms

The usual xterm program that is installed with graphical desktops is very functional, but also uses quite a lot of system resource. If you are running a system with many X terminal clients running on a single processor, you may want to consider using a lighter-weight terminal. Two such are rxvt and aterm (which was built on top of rxvt ). These are VT102 emulators, which are not usually installed by default, so you will need to install them.

Required libraries

By now you may be realizing that there are many different libraries and toolkits that are used for X applications. So how do you ensure that you have the right libraries? The ldd command lists library dependencies for any application. In its simplest form, it takes the name of an executable and prints out the libraries required to run the program. Note that ldd does not automatically search your PATH, so you usually need to give the path (relative or absolute) as well as the program name, unless the program is in the current directory. Listing 24 shows the library dependencies for the three terminal emulators that you saw above. The number of library dependencies for each gives you a clue about the relative system requirements of each.

Listing 24. Library dependencies for xterm, aterm, and rxvt

root@pinguino:~# ldd `which xterm`

linux-gate.so.1 => (0xffffe000)

libXft.so.2 => /usr/X11R6/lib/libXft.so.2 (0xb7fab000)

libfontconfig.so.1 => /usr/X11R6/lib/libfontconfig.so.1 (0xb7f88000)

libfreetype.so.6 => /usr/X11R6/lib/libfreetype.so.6 (0xb7f22000)

libexpat.so.0 => /usr/X11R6/lib/libexpat.so.0 (0xb7f06000)

libXrender.so.1 => /usr/X11R6/lib/libXrender.so.1 (0xb7eff000)

libXaw.so.7 => /usr/X11R6/lib/libXaw.so.7 (0xb7ead000)

libXmu.so.6 => /usr/X11R6/lib/libXmu.so.6 (0xb7e99000)

libXt.so.6 => /usr/X11R6/lib/libXt.so.6 (0xb7e4f000)

libSM.so.6 => /usr/X11R6/lib/libSM.so.6 (0xb7e46000)

libICE.so.6 => /usr/X11R6/lib/libICE.so.6 (0xb7e30000)

libXpm.so.4 => /usr/X11R6/lib/libXpm.so.4 (0xb7e22000)

libXext.so.6 => /usr/X11R6/lib/libXext.so.6 (0xb7e15000)

libX11.so.6 => /usr/X11R6/lib/libX11.so.6 (0xb7d56000)

libncurses.so.5 => /lib/libncurses.so.5 (0xb7d15000)

libc.so.6 => /lib/tls/i686/cmov/libc.so.6 (0xb7be6000)

libdl.so.2 => /lib/tls/i686/cmov/libdl.so.2 (0xb7be3000)

/lib/ld-linux.so.2 (0xb7fc3000)

root@pinguino:~# ldd `which aterm`

linux-gate.so.1 => (0xffffe000)

libXpm.so.4 => /usr/X11R6/lib/libXpm.so.4 (0xb7f81000)

libX11.so.6 => /usr/X11R6/lib/libX11.so.6 (0xb7ec1000)

libSM.so.6 => /usr/X11R6/lib/libSM.so.6 (0xb7eb9000)

libICE.so.6 => /usr/X11R6/lib/libICE.so.6 (0xb7ea3000)

libc.so.6 => /lib/tls/i686/cmov/libc.so.6 (0xb7d75000)

libdl.so.2 => /lib/tls/i686/cmov/libdl.so.2 (0xb7d72000)

/lib/ld-linux.so.2 (0x80000000)

root@pinguino:~# ldd `which rxvt`

linux-gate.so.1 => (0xffffe000)

libX11.so.6 => /usr/X11R6/lib/libX11.so.6 (0xb7eb0000)

libc.so.6 => /lib/tls/i686/cmov/libc.so.6 (0xb7d81000)

libdl.so.2 => /lib/tls/i686/cmov/libdl.so.2 (0xb7d7e000)

/lib/ld-linux.so.2 (0x80000000)Exporting a display

An X display is known by a name of the form hostname:displaynumber.screennumber . For Linux running on a workstation such as a PC, there is typically only one display with a single screen. In this case, the displayname may be, and usually is, omitted so the display is known as :0.0. The DISPLAY environment variable is usually set to the display name., so you can display it using the command echo $DISPLAY . Depending on your system, this variable may or may not be set if you use su - to switch to another user. In such a case, you may need to set and export the DISPLAY as shown in Listing 25. In this listing you see an attempt to start the xclock application after switching to root, but the attempt fails because the DISPLAY environment variable is not set. Even if the DISPLAY variable is set, you still may not be able to use the display, as you will also need authorization to do so.

Listing 25. Attempting to start xclock

ian@lyrebird:~> whoami

ian

ian@lyrebird:~> echo $DISPLAY

:0.0

ian@lyrebird:~> su -

Password:

lyrebird:~ # echo $DISPLAY

lyrebird:~ # xclock

Error: Can't open display:

lyrebird:~ # export DISPLAY=:0.0

lyrebird:~ # echo $DISPLAY

:0.0

lyrebird:~ # xclock

Xlib: connection to ":0.0" refused by server

Xlib: No protocol specified

Error: Can't open display: :0.0

lyrebird:~ # export XAUTHORITY=~ian/.Xauthority

lyrebird:~ # xclock

lyrebird:~ # ls -l ~ian/.Xauthority

-rw------- 1 ian users 206 Feb 18 16:20 /home/ian/.Xauthority Let's take a look at what is going on here. In this case, the user ian logged in to the system and his DISPLAY environment was set to :0.0 as we expect. When user ian switched to user root, the DISPLAY environment variable was not set, and an attempt to start xclock failed because the application did not know what display to use.

So the substituted user, root, set the DISPLAY environment variable, and exported it so that it would be available to other shells that might be started from this terminal window. Note that setting and exporting an environment variable does not use the leading $ sign, while displaying or otherwise using the value does. Note too, that if the su command had omitted the - (minus) sign, the DISPLAY environment variable would have been set as it had been for user ian. Nevertheless, even with the environment variable set, xclock still failed.

The reason for the second failure lies in the client/server nature of X. Although root is running in a window on the one and only display on this system, the display is actually owned by the user who logged in originally, ian in this case. Let's take a look at X authorization.

Authorization methods

For local displays on Linux systems, authorization usually depends on a so-called MIT-MAGIC-COOKIE-1 , which is usually regenerated every time the X server restarts. A user can extract the magic cookie from the .Xauthority file in his or her home directory (using the xauth extract command and give it to another user to merge into that user's .Xauthority file using the xauth merge command. Alternatively, a user can grant authority for other users to access the local system using the xhost +local: command.

XAUTHORITY

Another alternative is to set the XAUTHORITY environment variable to the location of a file containing the appropriate MIT-MAGIC-COOKIE-1. When switching to root, it is easy to do this, since root can read files owned by other users. This is, in fact, what we did in Listing 25, so after setting and exporting XAUTHORITY to ~ian/.Xauthority, root is now able to open graphical windows on the desktop. We said we'd mention a difference with Red Hat systems. Using su to switch to root on a Red Hat system is slightly different on a SUSE system, where the display setup is done automatically for you.

So what if you switch to another non-root user? You will notice from Listing 25 that the .Xauthority file for user ian allows only user read and write access. Even members of the same group cannot read it, which is what you want unless you'd like someone to open up an application that takes over your screen and prevents you from doing anything! So, if you do extract an MIT-MAGIC-COOKIE-1 from your .Xauthority file, then you have to find some secure way to give it to your friendly non-root user. Another approach is to use the xhost command to grant authority to any user on a particular host.

The xhost command

Because of the difficulty of securely passing an MIT-MAGIC-COOKIE-1 cookie to another user, you may find that, for a Linux system with a single user, xhost is easier to use, even though the xauth approach is generally preferred over the xhost command, However, keep in mind the network heritage of the X Window System so that you do not accidentally grant more access than you intended and thereby open up your system and allow arbitrary network users to open windows on your desktop.

To give all local users authority to open applications on the display (:0.0), user ian can use the xhost command. Open a terminal window on your desktop and enter this command:

xhost +local:

Note the trailing colon (:). This will allow other users on the same system to connect to the X server and open windows. Since you are a single-user system, this means that you can su to an arbitrary non-root user and can now launch xclock or other X applications.

You may also use xhost to authorize remote hosts. This is generally not a good idea except on restricted networks. You will also need to enable the appropriate ports on your firewall if you are using one.

Another alternative for using X applications from another system is to connect to the system using a secure shell ( ssh ) connection. If your default ssh client configuration does not enable X forwarding, you may need to add the -X parameter to your ssh command. The ssh server will also need to have X forwarding enabled. In general, this is a much more secure method of using X remotely than opening up your system to arbitrary connections using xhost .

For more details on using the xauth and xhost commands, you can use the commands info xauth , man xauth , info xhost , or man xhost as appropriate to view the online manual pages. If you are interested in security for X connections, start with the manual pages for Xsecure .

翻译自: https://www.ibm.com/developerworks/linux/tutorials/l-lpic1110/index.html