We mentioned last time that in the first conflict between particle and wave, the particle theory led by Newton beat the wave theory and gained the wide acknowledgment in physics academia.

After a century passed, Newton’s system owned so high a social status that it dazzled people’s eyes. And what he advocated - the notion that light is a kind of particles was so firmly believed that people almost forgot about its former opponent.

However, on 13th June 1773, in a Puritan household in Milverton England, a boy was born, whose name was Thomas Young. This leader of the future’s rebel force owned a typical genius-typed way of growth: he began reading all kinds of classics at an age of 2, studying Latin at 6; at the age of 14 he wrote an autobiography in Latin; by the age of 16, he could speak 10 languages. His talent in language later made him capable of interpreting many mysterious Egyptian hieroglyphs on the Tarot. But for our story, more importantly, Young was interested in natural science, too. He learned Newton’s Principia Mathematica and Lavoisier’s Traite Elementaire de Chimie, and these grand works laid the foundation for his future achievement.

At the age of 19, with the impact from his uncle, Young made up his mind to learn medical science in London. Later, he went to Edinburgh University and University of Gottingen. He finalized his learning back in Emanuel College in Cambridge University. At the time when he was still a student, Young studied the structure of human eyes and he began to get contact with some fundamental questions in optics, and finally that formed the idea that light was a wave. Young’s this idea originated from the “interference” phenomenon.

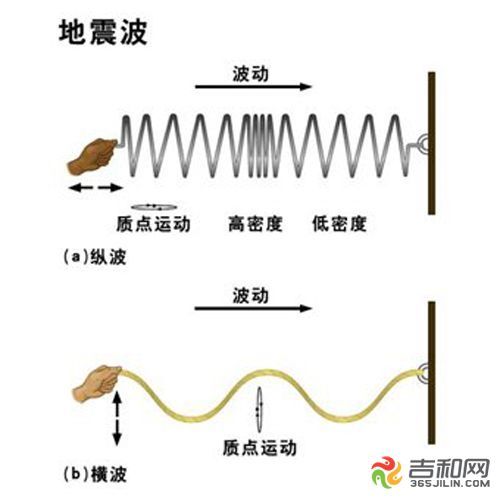

As we know, the common substances are accumulative: a drop of water adding another drop makes two drops instead of vanishing together. But that’s not the case of wave. An array of common wave has its peaks and troughs. Then when two arrays meet, the peak will be twice as high as before if two peaks meet while the tough will be twice as low as before if two troughs meet. However, what if a peak of one wave meets a trough of another?

The answer is they will cancel out each other. If two waves meet under such a circumstance (it’s called “reverse phase” in physics), the overlap will be just flat, no peak nor trough. It’s just like someone is pulling you to the left, while another man is pulling with the same force towards the right, and as a result, you main still.

Thomas Young got deeply moved by this wave idea when studying the light-dark stripes of the Newton’s Ring. Why stripes? If we employ wave to explain, isn’t it such an easy case? At the “light” places, the two lights are just with the “same phase”, and their peaks and troughs strengthen each other, resulting in twice as luminous as before; at the “dark” places, the two lights must be of “reverse phase” with their peaks and troughs opposing each other, resulting in canceling out each other. This bold yet imaginary idea thrilled Young, and then he carried out a series of experiment and published his essays in 1801 and 1803, explaining how to use the interference effect of light wave to interpret Newton’s Ring and diffraction. Even through his data, the wavelength of light was calculated with a value between 1/36000 and 1/60000 inch.

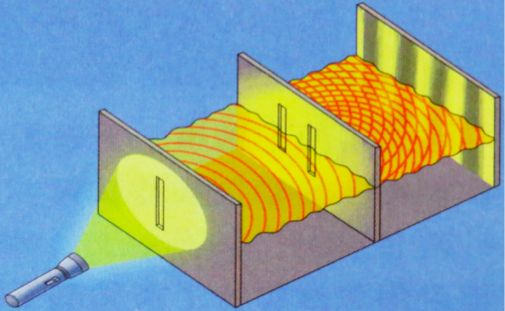

In the year 1807, Young summarized and published his A Course of Lectures on Natural Philosophy. In it, he comprehensively summarized his work in optics and for the first time introduced his world-renown experiment - the double-slit diffraction of light. Later, history proved that this experiment could be among the top 5 most classic experiments in the history of physics. And today, it appears on every textbook of middle school physics.

The experiment method is easy: put a candle in front of a piece of paper with a hole, resulting in a dot light source. Now put another piece of paper after that paper but in your second piece there are two paralleled slits. The light coming through the first hole will travel through the two slits and is projected onto a screen, forming a series of light-dark stripes, known as “the interference stripes”.

Young’s book ignited the powderhose of revolution, and the “Second Wave-particle War” started. After century long silence, the wave army got back to the stage of history. But at that time, they were leading a poor life. The particle army was well equipped and dominant over the battleground while the soldiers in wave army lacked backups and they could only fight like guerrilla so that they could draw the public’s attention from time to time. Young’s essays at first were mocked and tagged as “ridiculous” and “irrational”. Nobody cared about his theory in about 20 years. To defend himself, Young wrote another essay in specific, but he found no place to publish it. Then he had to print it into pamphlets, but it was said that “only one copy had been sold”.

Although the rebellion force seemed vulnerable, after several heavy blows, the canon of the interference stripes finally shocked the whole particle army. This simple but intricate experiment showed some phenomena with proofs so convincing: how to explain the darkness caused by the meet of two lights. The explanation from wave is straightforward: the distances between the two slits and some point on the screen are different. If the difference of their distances equals to the integral times of the wavelength, the two light waves strengthen each other and a luminous stripe is obtained. On the contrary, if the difference equals to half of the wavelength, the two waves cancel out each other, and it results in a dark stripe. The theoretically calculated result of the gap between stripes matched perfectly with the experimental data.

To fight back, particle army proposed many experimental proof to verify the paradox of the wave. The most famous one is the polarization phenomenon discovered by Etienne Louis Malus in 1809. In Young’s letter addressed to Malus, he wrote, “... your experiment only proved that my theory isn’t flawless, but it didn’t prove that it’s fake.”

The decisive moment came in 1819. The final duel originated from an essay contest of Academie des sciences (The Academy of Science of France). The question of the contest is to confirm the diffraction effect of light with sophisticated apparatuses and derive the behavior of motion for lights traveling near an object. The judging panel consisted of many renown scientists, among whom were J. B. Biot, Pierre Simon de Laplace and S. D. Poisson, advocates of the particle theory. The original intention was to explain the motion and diffraction of light through the particle theory, thus it could give a heavy blow to the wave theory.

But something dramatic happened: an unknown young French engineer, Augustin Fresnel, 31-year-old, submitted an essay to the panel. In this essay, Fresnel adopted the idea that light was wave, and through precise mathematical reasoning, he perfectly explained about the diffraction of light. The judging panel were amazed by his system. Poisson didn’t believe it, but he underwent careful investigation and he discovered that if applying this theory to the round-plate diffraction, in the middle of the shadow, a light spot emerged. This seems too ridiculous to Poisson. But another judge, a colleague of Fresnel, Francois Arago, insisted on an experimental detection of it. And as a result, like a miracle, a light spot emerged at the center of the shadow of the plate.

The victory of Fresnel theory was a decisive incident in the Second Particle-wave War. He was awarded the Grand Prix, and he was regarded as another legendary icon among Newton and Huygens. The light spot in the center (misleadingly called “Poison spot) became another heavy weapon of the wave army. The beacon-fire of the rebellion force soon spread over the whole territory of optics. However, the polarization of lights remained unsolved. Particle army was still shooting fire upon the wave army. Thus, Fresnel made another decision: he hypothesized that light was a horizontal wave (like the water wave, the oscillation direction of the oscillator is perpendicular to the direction of the transmission), instead of a vertical wave (the oscillator oscillates along the direction of transmission, like a spring) as Hooke and his followers thought it would be. In the year 1812, Fresnel published his essay “On the interaction of polarized lights”, explained successfully the polarization phenomenon with horizontal wave theory. It conquered the most difficult fortified point.

The day of the great counterstike arrived. In the mid-19th century, the only hope that particle army could hold to was the speed of light measured in water. According to the particle theory, the speed should be faster than in vacuum, while in the wave theory, it should be slower.

Unfortunately, particle army met its Waterloo again in 1850 after the bitter winter of 1819 in Moscow. In May 6th 1850, Jean-Bernard-Leon Foucault (he became famous later for his “Foucault pendulum”) submitted a report to Academie des sciences about his test result of the speed of light. After obtaining the accurate value of light speed in vacuum, he also undertook the measurement of light speed in water, discovering a value smaller than that in vacuum, only 3/4 as much as the former. This result sentenced the particle theory a death penalty. After 100 years, the wave theory finally succeed in overturning the reign of particle. The Second Particle-wave War ended in the success of the wave.

However, Fresnel’s horizontal wave theory also left a difficulty for the wave army: aether. The speed of light reaches a value of 0.3 million kilometer per second. According to the traditional wave theory, it was not difficult to infer the property of its transmission medium: the medium must be a super-hard solid, a great harder than the hardest substance - diamond. But the fact was nobody could really “feel” or “see” this “aether”, nor could any experiment show its existence. Starlight traveled many million billion kilometers of aether to reach our earth, yet aether with unparalleled hardness could not hinder the motion of any planet or even a dust!

The explanation from the wave was that aether was a rigid particle but it was so rarefied that the substance didn’t feel any resistance when traveling though it, “it’s like a wind traveling through a forest” (by Thomas Young). Aether stood absolutely still in vacuum. And only inside a transparent object, it could be partly dragged along.

This idea was not convincing enough, but it didn’t confuse the wave theory for a long time, because soon afterward, a more thrilling victory was coming. Maxwell the great in 1856, 1861, and 1865 published three essays on electromagnetics. This great work built up another giant infrastructure on the mansion of Newton mechanics. Maxwell theory foretold that light, in essence, was a kind of electromagnetic wave. This was written down in italic in his second essay On Physical Lines of Force in 1861. And we have read at the beginning of this chapter that how this prophecy got proved by Hertz’s experiment in 1887. The brilliance of wave reached its peak point. Its power, like the power of the giants in ancient Greek mythology, was invincible. And the earth it relied upon, was the immortal electromagnetic theory by Maxwell.