New Words and phrases

1. slope |slōp|

noun

1 a surface of which one end or side is at a higher level than another; a rising or falling surface: he slithered helplessly down the slope.

• a difference in level or sideways position between the two ends or sides of a thing: the roof should have a slope sufficient for proper drainage | the backward slope of the chair.

• (often slopes) a part of the side of a hill or mountain, especially as a place for skiing: a ten-minute cable-car ride delivers you to the slopes.

• the gradient of a graph at any point.

• Electronics the transconductance of a valve, numerically equal to the gradient of one of the characteristic curves of the valve.

2 US informal, offensive a person from Asia, especially Vietnam or elsewhere in Southeast Asia.

verb [no object]

(of a surface or line) be inclined from a horizontal or vertical line; slant up or down: the garden sloped down to a stream | the ceiling sloped.

• [with object] place or arrange in a sloping position: Poole sloped his shoulders | (as adjective sloped) : a sloped leather writing surface.

ORIGIN

late 16th century (as a verb): from the obsolete adverb slope, a shortening of aslope.

2. set aside

v.

1> give or assign a resource to a particular person or cause

synonymous: allow, appropriate, earmark, reserve

2> make inoperative or stop

synonymous: suspend

adj.

reserved in advance

synonymous: booked, engaged, set-aside(p)

3. refute |rəˈfyo͞ot|

verb [with object]

prove (a statement or theory) to be wrong or false; disprove: these claims have not been convincingly refuted.

• prove that (someone) is wrong.

• deny or contradict (a statement or accusation): a spokesman totally refuted the allegation of bias.

DERIVATIVES

refutable |rəˈfyo͞odəbəlrēˈfyo͞odəbəlˈrefyədəbəl| adjective.

refutal |rəˈfyo͞odl| noun( rare).

refuter |rəˈfyo͞odər| noun

ORIGIN

mid 16th century: from Latin refutare ‘repel, rebut.’

usage: The core meaning of refute is ‘prove a statement or theory to be wrong,’ as in attempts to refute Einstein's theory. In the second half of the 20th century, a more general sense developed, meaning simply ‘deny,’ as in I absolutely refute the charges made against me. Traditionalists object to this newer use as an unacceptable degradation of the language, but it is widely encountered.

4. propagation |ˌpräpəˈɡāSH(ə)n|

noun

1 the breeding of specimens of a plant or animal by natural processes from the parent stock: the propagation of plants by root cuttings | [as modifier] : propagation techniques such as grafting.

• reproduction by natural processes: hunting regulations ensure the propagation of the species | asexual propagation is the primary mode of reproduction.

2 the action of widely spreading and promoting an idea, theory, etc.: a life devoted to the propagation of the Catholic faith | the propagation of ideas was important.

3 transmission of motion, light, sound, etc., in a particular direction or through a medium: the propagation of radio waves through space | the physics of light propagation.

5. ripple |ˈripəl|

noun

1 a small wave or series of waves on the surface of water, especially as caused by an object dropping into it or a slight breeze.

• a thing resembling a ripple or ripples in appearance or movement: the sand undulated and was ridged with ripples.

• a gentle rising and falling sound, especially of laughter or conversation, that spreads through a group of people: a ripple of laughter ran around the room.

• a particular feeling or effect that spreads through or to someone or something: his words set off a ripple of excitement within her.

• Physics a wave on a fluid surface, the restoring force for which is provided by surface tension rather than gravity, and that consequently has a wavelength shorter than that corresponding to the minimum speed of propagation.

• Physics small periodic, usually undesirable, variations in electrical voltage superposed on a direct voltage or on an alternating voltage of lower frequency.

2 a type of ice cream with wavy lines of colored flavored syrup running through it: raspberry ripple.

verb [no object]

(of water) form or flow with small waves on the surface: the Mediterranean rippled and sparkled | (as adjective rippling) : the rippling waters.

• [with object] cause (the surface of water) to form small waves: a cool wind rippled the surface of the estuary.

• move in a way resembling small waves: fields of grain rippling in the wind.

• (of a sound or feeling) spread through a person, group, or place: applause rippled around the tables.

• (as adjective rippled) having the appearance of small waves: a broad noodle, rippled on both sides, wider than fettuccine.

DERIVATIVES

ripplet |ˈriplit| noun.

ripply |ˈrip(ə)lē| adjective

ORIGIN

late 17th century (as a verb): of unknown origin.

6. crest |krest|

noun

1 a comb or tuft of feathers, fur, or skin on the head of a bird or other animal.

• a thing resembling a tuft, especially a plume of feathers on a helmet.

2 the top of something, especially a mountain or hill: she reached the crest of the hill.

• the curling foamy top of a wave.

• Anatomy a ridge along the surface of a bone.

• the upper line of the neck of a horse or other mammal.

3 Heraldry a distinctive device borne above the shield of a coat of arms (originally as worn on a helmet), or separately reproduced, for example on writing paper or silverware, to represent a family or corporate body.

verb [with object]

reach the top of (something such as a hill or wave): she crested a hill and saw the valley spread out before her.

• [no object] US (of a river) rise to its highest level: the river was expected to crest at eight feet above flood stage.

• [no object] (of a wave) form a curling foamy top.

• (be crested) have attached or affixed at the top: his helmet was crested with a fan of spikes.

DERIVATIVES

crestless adjective

ORIGIN

Middle English: from Old French creste, from Latin crista ‘tuft, plume.’

7. infrared |ˌinfrəˈred|

adjective

(of electromagnetic radiation) having a wavelength just greater than that of the red end of the visible light spectrum but less than that of microwaves. Infrared radiation has a wavelength from about 800 nm to 1 mm, and is emitted particularly by heated objects.

• (of equipment or techniques) using or concerned with this radiation: infrared cameras.

noun

the infrared region of the spectrum; infrared radiation.

8. ether |ˈēTHər|

noun

1 Chemistry a pleasant-smelling, colorless, volatile liquid that is highly flammable. It is used as an anesthetic and as a solvent or intermediate in industrial processes.

[Alternative names: diethyl ether, ethoxyethane; chemical formula: C 2H 5OC 2H 5.]

• any organic compound with a structure similar to ether, having an oxygen atom linking two alkyl or other organic groups: methyl t-butyl ether.

2 (also aether) chiefly literary the clear sky; the upper regions of air beyond the clouds: nasty gases and smoke disperse into the ether.

• (the ether) informal air regarded as a medium for radio: choral evensong still wafts across the ether.

3 (also aether) Physics, archaic a very rarefied and highly elastic substance formerly believed to permeate all space, including the interstices between the particles of matter, and to be the medium whose vibrations constituted light and other electromagnetic radiation.

DERIVATIVES

etheric |iˈTHerik, iˈTHi(ə)rik| adjective

ORIGIN

late Middle English: from Old French, or via Latin from Greek aithēr ‘upper air,’ from the base of aithein ‘burn, shine.’ Originally the word denoted a substance believed to occupy space beyond the sphere of the moon. Sense 3 arose in the mid 17th century and sense 1 in the mid 18th century.

9. hitherto |ˌhiT͟Hərˈto͞o|

adverb

until now or until the point in time under discussion: there is a need to replace what has hitherto been a haphazard method of payment.

10. patent

noun |ˈpatnt|

1 a government authority or license conferring a right or title for a set period, especially the sole right to exclude others from making, using, or selling an invention: he took out a patent for an improved steam hammer. Compare with letters patent.

2 short for patent leather.

adjective

1 |ˈpātntˈpatnt| easily recognizable; obvious: she was smiling with patent insincerity.

2 Medicine |ˈpātntˈpatnt| (of a vessel, duct, or aperture) open and unobstructed; failing to close.

• (of a parasitic infection) showing detectable parasites in the tissues or feces.

3 |ˈpatnt| [attributive] made and marketed under a patent; proprietary: patent milk powder.

verb |ˈpatnt| [with object]

obtain a patent for (an invention): an invention is not your own until it is patented.

DERIVATIVES

patentability |ˌpatn(t)əˈbilədē| noun.

patentable |ˈpatn(t)əb(ə)l| adjective

ORIGIN

late Middle English: from Old French, from Latin patent- ‘lying open,’ from the verb patere .

11. postulate

verb |ˈpäsCHəˌlāt| [with object]

1 suggest or assume the existence, fact, or truth of (something) as a basis for reasoning, discussion, or belief: his theory postulated a rotatory movement for hurricanes | [with clause] : he postulated that the environmentalists might have a case.

2 (in ecclesiastical law) nominate or elect (someone) to an ecclesiastical office subject to the sanction of a higher authority.

noun |ˈpäsCHələt| formal

a thing suggested or assumed as true as the basis for reasoning, discussion, or belief: perhaps the postulate of Babylonian influence on Greek astronomy is incorrect.

• Mathematics an assumption used as a basis for mathematical reasoning.

DERIVATIVES

postulation |ˌpäsCHəˈlāSH(ə)n| noun

ORIGIN

late Middle English ( sense 2 of the verb): from Latin postulat- ‘asked,’ from the verb postulare .

12. intrinsic |inˈtrinzikinˈtrinsik|

adjective

belonging naturally; essential: access to the arts is intrinsic to a high quality of life.

• (of a muscle) contained wholly within the organ on which it acts.

ORIGIN

late 15th century (in the general sense ‘interior, inner’): from French intrinsèque, from late Latin intrinsecus, from the earlier adverb intrinsecus ‘inwardly, inward.’

13. cesium |ˈsēzēəm| (British caesium)

noun

the chemical element of atomic number 55, a soft, silvery, extremely reactive metal. It belongs to the alkali metal group and occurs as a trace element in some rocks and minerals.(Symbol: Cs)

ORIGIN

mid 19th century: from Latin caesius ‘grayish-blue’ (because it has characteristic lines in the blue part of the spectrum).

14. Piccadilly Circus

a place in central London where several major roads converge on a large public space.

PHRASES

be like Piccadilly Circus

British informal be very busy or crowded: last week it was like Piccadilly Circus in here, with builders, plumbers, and decorators working flat out to get the house ready.

15. overlap

verb |ˌōvərˈlap| (overlaps, overlapping, overlapped) [with object]

extend over so as to cover partly: the canopy overlaps the house roof at one end | [no object] : the curtains overlap at the center when closed.

• [no object] cover part of the same area of interest, responsibility, etc.: their duties sometimes overlapped.

• [no object] partly coincide in time: two new series overlapped.

noun |ˈōvərˌlap|

a part or amount that overlaps: an overlap of about half an inch.

• a common area of interest, responsibility, etc.: there are many overlaps between the approaches | there is some overlap in requirements.

• a period of time in which two events or activities happen together.

16. diagonal |dīˈaɡənl| (abbreviation diag.)

adjective

(of a straight line) joining two opposite corners of a square, rectangle, or other straight-sided shape.

• (of a line) straight and at an angle; slanting: a tie with diagonal stripes.

noun

a straight line joining two opposite corners of a square, rectangle, or other straight-sided shape.

• Mathematics the set of elements of a matrix that lie on a line joining two opposite corners.

• a slanting straight pattern or line: the bars of light made diagonals across the entrance | tiles can be laid on the diagonal.

• Chess a slanting row of squares whose color is the same.

ORIGIN

mid 16th century: from Latin diagonalis, from Greek diagōnios ‘from angle to angle,’ from dia ‘through’ + gōnia ‘angle.’

17. cone |kōn|

noun

1 a solid or hollow object that tapers from a circular or roughly circular base to a point.

• Mathematics a surface or solid figure generated by the straight lines that pass from a circle or other closed curve to a single point (the vertex) not in the same plane as the curve. A cone with the vertex perpendicularly over the center of a circular base is a right circular cone.

• (also traffic cone) a plastic cone-shaped object that is used to separate off or close sections of a road.

• an edible wafer container shaped like a cone in which ice cream is served.

• a conical mountain or peak, especially one of volcanic origin.

• (also pyrometric cone) a ceramic pyramid that melts at a known temperature and is used to indicate the temperature of a kiln.

• short for cone shell.

2 the dry fruit of a conifer, typically tapering to a rounded end and formed of a tight array of overlapping scales on a central axis that separate to release the seeds.

• a flower resembling a pine cone, especially that of the hop plant.

3 Anatomy a light-sensitive cell of one of the two types present in the retina of the eye, responding mainly to bright light and responsible for sharpness of vision and color perception. Compare with rod ( sense 5).

ORIGIN

late Middle English (denoting an apex or vertex): from French cône, via Latin from Greek kōnos .

18. warp |wôrp|

verb

1 become or cause to become bent or twisted out of shape, typically as a result of the effects of heat or dampness: [no object] : wood has a tendency to warp | [with object] : moisture had warped the box.

• [with object] cause to become abnormal or strange; have a distorting effect on: your judgment has been warped by your obvious dislike of him | (as adjective warped) : a warped sense of humor.

2 [with object] move (a ship) along by hauling on a rope attached to a stationary object on shore.

• [no object] (of a ship) move by being hauled on a rope attached to a stationary object.

3 [with object] (in weaving) arrange (yarn) so as to form the warp of a piece of cloth.

4 [with object] cover (land) with a deposit of alluvial soil by natural or artificial flooding.

noun

1 a twist or distortion in the shape or form of something: the head of the racket had a curious warp.

• [as modifier] relating to or denoting (fictional or hypothetical) space travel by means of distorting space-time: the craft possessed warp drive | warp speed.

• an abnormality or perversion in a person's character.

2 [in singular] (in weaving) the threads on a loom over and under which other threads (the weft) are passed to make cloth: the warp and weft are the basic constituents of all textiles | figurative : rugby is woven into the warp and weft of South African society.

3 a rope attached at one end to a fixed point and used for moving or mooring a ship.

4 archaic alluvial sediment; silt.

DERIVATIVES

warpage |ˈwôrpij| noun.

warper |ˈwôrpər| noun

ORIGIN

Old English weorpan (verb), wearp (noun), of Germanic origin; related to Dutch werpen and German werfen ‘to throw.’ Early verb senses included ‘throw,’ ‘fling open,’ and ‘hit (with a missile)’; the sense ‘bend’ dates from late Middle English. The noun was originally a term in weaving ( sense 2 of the noun) .

19. geodesic |ˌjēəˈdesikˌjēəˈdēsik|

adjective

1 relating to or denoting the shortest possible line between two points on a sphere or other curved surface.

2 another term for geodetic.

geodetic |ˌjēəˈdedik|

adjective

relating to geodesy, especially as applied to land surveying.

ORIGIN

late 17th century: from Greek geōdaitēs ‘land surveyor,’ from geōdaisia (see geodesy) .

noun

a geodesic line or structure.

20. hail 1 |hāl|

noun

pellets of frozen rain that fall in showers from cumulonimbus clouds.

• [in singular] a large number of objects hurled forcefully through the air: a hail of bullets.

verb [no object]

1 (it hails, it is hailing, etc.) hail falls: it hailed so hard we had to stop.

2 [with adverbial of direction] (of a large number of objects) fall or be hurled forcefully: missiles and bombs hail down from the sky.

ORIGIN

Old English hagol, hægl (noun), hagalian (verb), of Germanic origin; related to Dutch hagel and German Hagel .

hail 2 |hāl|

verb

1 [with object] call out to (someone) to attract attention: the crew hailed a fishing boat.

• signal (an approaching taxicab) to stop: she raised her hand to hail a cab.

2 [with object] acclaim enthusiastically as being a specified thing: he has been hailed as the new James Dean.

3 [no object] (hail from) have one's home or origins in (a place): he hails from Pittsburgh.

exclam. archaic

expressing greeting or acclaim: hail, Caesar!

noun

a shout or call used to attract attention.

PHRASES

within hail

(or within hailing distance) at a distance within which someone may be called to; within earshot.

DERIVATIVES

hailer noun

ORIGIN

Middle English: from the obsolete adjective hail ‘healthy’ (occurring in greetings and toasts, such as wæs hæil: see wassail), from Old Norse heill, related to hale1 and whole.

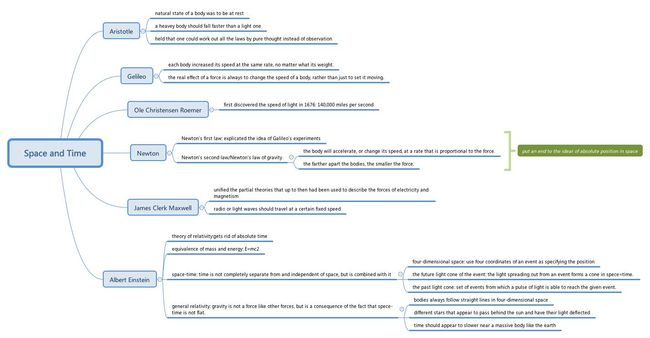

Mindmap

Some concepts

1. nature is everywhere the cause of order.

— Aristotle, Physics VIII.1

While consistent with common human experience, Aristotle's principles were not based on controlled, quantitative experiments, so, while they account for many broad features of nature, they do not describe our universe in the precise, quantitative way now expected of science. Contemporaries of Aristotle like Aristarchus rejected these principles in favor of heliocentrism, but their ideas were not widely accepted. Aristotle's principles were difficult to disprove merely through casual everyday observation, but later development of the scientific method challenged his views with experiments and careful measurement, using increasingly advanced technology such as the telescope and vacuum pump.

2. Galileo proposed that a falling body would fall with a uniform acceleration, as long as the resistance of the medium through which it was falling remained negligible, or in the limiting case of its falling through a vacuum. He also derived the correct kinematical law for the distance travelled during a uniform acceleration starting from rest—namely, that it is proportional to the square of the elapsed time ( d ∝ t 2 ). Prior to Galileo, Nicole Oresme, in the 14th century, had derived the times-squared law for uniformly accelerated change, and Domingo de Soto had suggested in the 16th century that bodies falling through a homogeneous medium would be uniformly accelerated. Galileo expressed the time-squared law using geometrical constructions and mathematically precise words, adhering to the standards of the day. (It remained for others to re-express the law in algebraic terms).

He also concluded that objects retain their velocity in the absence of any impediments to their motion,[citation needed] thereby contradicting the generally accepted Aristotelian hypothesis that a body could only remain in so-called "violent", "unnatural", or "forced" motion so long as an agent of change (the "mover") continued to act on it. Philosophical ideas relating to inertia had been proposed by John Philoponus and Jean Buridan. Galileo stated: "Imagine any particle projected along a horizontal plane without friction; then we know, from what has been more fully explained in the preceding pages, that this particle will move along this same plane with a motion which is uniform and perpetual, provided the plane has no limits." This was incorporated into Newton's laws of motion (first law).

3. Newton's law of universal gravitation states that a particle attracts every other particle in the universe using a force that is directly proportional to the product of their masses and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between them. This is a general physical law derived from empirical observations by what Isaac Newton called inductive reasoning. It is a part of classical mechanics and was formulated in Newton's work Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica ("the Principia"), first published on 5 July 1687. (When Newton's book was presented in 1686 to the Royal Society, Robert Hooke made a claim that Newton had obtained the inverse square law from him; see the History section below.)

In modern language, the law states: Every point mass attracts every single other point mass by a force pointing along the line intersecting both points. The force is proportional to the product of the two masses and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between them. The first test of Newton's theory of gravitation between masses in the laboratory was the Cavendish experiment conducted by the British scientist Henry Cavendish in 1798. It took place 111 years after the publication of Newton's Principia and approximately 71 years after his death.

Newton's law of gravitation resembles Coulomb's law of electrical forces, which is used to calculate the magnitude of the electrical force arising between two charged bodies. Both are inverse-square laws, where force is inversely proportional to the square of the distance between the bodies. Coulomb's law has the product of two charges in place of the product of the masses, and the electrostatic constant in place of the gravitational constant.

Newton's law has since been superseded by Albert Einstein's theory of general relativity, but it continues to be used as an excellent approximation of the effects of gravity in most applications. Relativity is required only when there is a need for extreme precision, or when dealing with very strong gravitational fields, such as those found near extremely massive and dense objects, or at very close distances (such as Mercury's orbit around the Sun).

4. Rømer's determination of the speed of light was the demonstration in 1676 that light has a finite speed, and so does not travel instantaneously. The discovery is usually attributed to Danish astronomer Ole Rømer (1644–1710), who was working at the Royal Observatory in Paris at the time.

By timing the eclipses of the Jupiter moon Io, Rømer estimated that light would take about 22 minutes to travel a distance equal to the diameter of Earth's orbit around the Sun. This would give light a velocity of about 220,000 kilometres per second in SI units, about 26% lower than the true value of 299,792 km/s.

Rømer's theory was controversial at the time he announced it, and he never convinced the director of the Paris Observatory, Giovanni Domenico Cassini, to fully accept it. However, it quickly gained support among other natural philosophers of the period, such as Christiaan Huygens and Isaac Newton. It was finally confirmed nearly two decades after Rømer's death, with the explanation in 1729 of stellar aberration by the English astronomer James Bradley.

5. The Michelson–Morley experiment was a scientific experiment to find the presence and properties of a substance called aether, a substance believed to fill empty space. The experiment was done by Albert Michelson and Edward Morley in 1887.

Since waves in water need something to move in (water) and sound waves do as well (air), it was believed that light also needed something to move in. Scientists in the 18th century named this substance "aether," after the Greek god of light. They believed that aether was all around us and that it also filled the vacuum of space. Michelson and Morley created this experiment to try and prove the theory that aether existed. They did this with a device called an interferometer.

The Earth travels very quickly (more than 100,000 km per hour) around the Sun. If aether exists, the Earth moving through it would cause a "wind" in the same way that there seems to be a wind outside a moving car. To a person in the car, the air outside the car would seem like a moving substance. In the same way, aether should seem like a moving substance to things on Earth.

The interferometer was designed to measure the speed and direction of the "aether wind" by measuring the difference between the speed of light traveling in different directions. It measured this difference by shining a beam of light into a mirror that was only partially coated in silver. Part of the beam would be reflected one way, and the rest would go the other. Those two parts would then be reflected back to where they were split apart, and recombined. By looking at interference patterns in the recombined beam of light, any changes in speed because of aether wind could be seen.

They found that there was in fact no substantial difference in the measurements. This was puzzling to the scientific community at the time, and led to the creation of various new theories to explain the result. The most important was Albert Einstein's special theory of relativity.

6. Albert Einstein, in his theory of special relativity, determined that the laws of physics are the same for all non-accelerating observers, and he showed that the speed of light within a vacuum is the same no matter the speed at which an observer travels.

Space-time is a mathematical model that joins space and time into a single idea called a continuum. This four-dimensional continuum is known as Minkowski space.

Combining these two ideas helped cosmology to understand how the universe works on the big level (e.g. galaxies) and small level (e.g. atoms).

In non-relativistic classical mechanics, the use of Euclidean space instead of space-time is good, because time is treated as universal with a constant rate of passage which is independent of the state of motion of an observer.

But in a relativistic universe, time cannot be separated from the three dimensions of space. This is because the observed rate at which time passes depends on an object's velocity relative to the observer. Also, the strength of any gravitational field slows the passage of time for an object as seen by an observer outside the field.

My Thoughts

Nothing can travel at a speed which is faster than that of light. As a result, we can not go back to the past. However, sometimes, i just wonder that if we could, could we go back to the past, to the place and time we lived before? Could there be the space-time that would hold the past events? As we saw in various movies, we travel through the time machine to the past and live another life there. Of course, there is no such machine, and there is no possibility that we can travel faster than light according to current scientific knowledge. We live in a place where time is not reversible. We live only once, and we should live at most of of it.