利用AVX指令集实现矩阵乘法

Recent Intel processors such as SandyBridge and IvyBridge have incorporated an instruction set called Advanced Vector Extensions, or AVX. This new addition to the spectrum of SIMD instructions makes the CPU even faster at crunching large amounts of floating point data. Matrix multiplication is a great candidate for performing optimizations via SIMD, since it involves mutually-independent multiplication and summing. To take advantage of the speed up, one could certainly inline a couple of assembly instructions. But this method is both inelegant and non-portable. The preferred approach is to use intrinsics instead.

What are instrinsics? Loosely speaking, intrinsics are functions that provide functionality equivalent to a few lines of assembly. Hence the assembly version can serve as a drop-in replacement to the function at compile-time. This allows performance-critical assembly code to be inlined without sacrificing the beauty and readability of the high-level language syntax. For example, the intrinsic function InterlockedExchange(LONG volatile *target, LONG value) atomically sets the data at the memory address held by target to value. This function will be replaced by a single inlined assembly xchg [target], value during compile time.

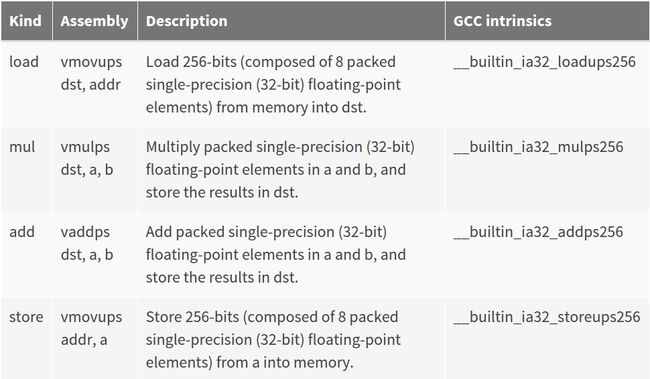

The Intel Intrinsics Guide provides detailed reference on SIMD instructions and their respective intrinsic versions. However, the GCC naming conventions for intrinsic functions are different from those used in Intel, hence additional lookups are required.

There are three types of instructions used:

load: moving data from memory to registers for calculation

arithmetic: batch operation on floating-point numbers in registers

and finally, store: moving data from registers back to memory for future processing

The respective instructions are listed below:

Using the instrinsic versions, one could write vectorized code with ease. The following is a simple example of multiplying two groups of 8 floats:

#include

#include ", ";

return 0;

} Note that the header

g++ -mavx main.cpp -o testThe -mavx switch enables gcc to emit avx instructions. Without it, the program will not compile. Once run, the program should output “2, 6, 12, 20, 30, 42, 56, 72,”.

To keep it simple, I first started with a reduced version of matrix multiplication: multiplying an n x m matrix with an m x 1 matrix, which is essentially a vector. E.g.

This is achieved by setting the element of the last matrix at the ith row and jth column to be the dot product between ith row of the first matrix and jth column of the second matrix.

To do the same process efficiently using AVX code, one could load up to 8 groups of 8 floats per matrix in an iteration, using the __builtin_ia32_loadups256 function, after which respective float numbers in the two matrix would be multiplied, and the results summed to give the dot product. The advantage of this approach is that there is prospect of further instruction-level parallelism and also less overhead in loop.

#include for (int j=0; jfloat)(rand()%1000)/800.0f;

}

}

for (int j=0; jfloat)(rand()%1000)/800.0f;

}

clock_t t1, t2;

t1 = clock();

for (int r = 0; r < num_trails; r++)

for(int j = 0; j < row; j++)

{

float sum = 0;

float *wj = w[j];

for(int i = 0; i < col; i++)

sum += wj[i] * x[i];

y[j] = sum;

}

t2 = clock();

float diff = (((float)t2 - (float)t1) / CLOCKS_PER_SEC ) * 1000;

cout<<"Time taken: "<for (int i=0; icout<", ";

}

cout<const int col_reduced = col - col%64;

const int col_reduced_32 = col - col%32;

for (int r = 0; r < num_trails; r++)

for (int i=0; ifloat res = 0;

for (int j=0; j64) {

ymm8 = __builtin_ia32_loadups256(&x[j]);

ymm9 = __builtin_ia32_loadups256(&x[j+8]);

ymm10 = __builtin_ia32_loadups256(&x[j+16]);

ymm11 = __builtin_ia32_loadups256(&x[j+24]);

ymm12 = __builtin_ia32_loadups256(&x[j+32]);

ymm13 = __builtin_ia32_loadups256(&x[j+40]);

ymm14 = __builtin_ia32_loadups256(&x[j+48]);

ymm15 = __builtin_ia32_loadups256(&x[j+56]);

ymm0 = __builtin_ia32_loadups256(&w[i][j]);

ymm1 = __builtin_ia32_loadups256(&w[i][j+8]);

ymm2 = __builtin_ia32_loadups256(&w[i][j+16]);

ymm3 = __builtin_ia32_loadups256(&w[i][j+24]);

ymm4 = __builtin_ia32_loadups256(&w[i][j+32]);

ymm5 = __builtin_ia32_loadups256(&w[i][j+40]);

ymm6 = __builtin_ia32_loadups256(&w[i][j+48]);

ymm7 = __builtin_ia32_loadups256(&w[i][j+56]);

ymm0 = __builtin_ia32_mulps256(ymm0, ymm8 );

ymm1 = __builtin_ia32_mulps256(ymm1, ymm9 );

ymm2 = __builtin_ia32_mulps256(ymm2, ymm10);

ymm3 = __builtin_ia32_mulps256(ymm3, ymm11);

ymm4 = __builtin_ia32_mulps256(ymm4, ymm12);

ymm5 = __builtin_ia32_mulps256(ymm5, ymm13);

ymm6 = __builtin_ia32_mulps256(ymm6, ymm14);

ymm7 = __builtin_ia32_mulps256(ymm7, ymm15);

ymm0 = __builtin_ia32_addps256(ymm0, ymm1);

ymm2 = __builtin_ia32_addps256(ymm2, ymm3);

ymm4 = __builtin_ia32_addps256(ymm4, ymm5);

ymm6 = __builtin_ia32_addps256(ymm6, ymm7);

ymm0 = __builtin_ia32_addps256(ymm0, ymm2);

ymm4 = __builtin_ia32_addps256(ymm4, ymm6);

ymm0 = __builtin_ia32_addps256(ymm0, ymm4);

__builtin_ia32_storeups256(scratchpad, ymm0);

for (int k=0; k<8; k++)

res += scratchpad[k];

}

for (int j=col_reduced; j32) {

ymm8 = __builtin_ia32_loadups256(&x[j]);

ymm9 = __builtin_ia32_loadups256(&x[j+8]);

ymm10 = __builtin_ia32_loadups256(&x[j+16]);

ymm11 = __builtin_ia32_loadups256(&x[j+24]);

ymm0 = __builtin_ia32_loadups256(&w[i][j]);

ymm1 = __builtin_ia32_loadups256(&w[i][j+8]);

ymm2 = __builtin_ia32_loadups256(&w[i][j+16]);

ymm3 = __builtin_ia32_loadups256(&w[i][j+24]);

ymm0 = __builtin_ia32_mulps256(ymm0, ymm8 );

ymm1 = __builtin_ia32_mulps256(ymm1, ymm9 );

ymm2 = __builtin_ia32_mulps256(ymm2, ymm10);

ymm3 = __builtin_ia32_mulps256(ymm3, ymm11);

ymm0 = __builtin_ia32_addps256(ymm0, ymm1);

ymm2 = __builtin_ia32_addps256(ymm2, ymm3);

ymm0 = __builtin_ia32_addps256(ymm0, ymm2);

__builtin_ia32_storeups256(scratchpad, ymm0);

for (int k=0; k<8; k++)

res += scratchpad[k];

}

for (int l=col_reduced_32; lfloat)t2 - (float)t1) / CLOCKS_PER_SEC ) * 1000;

cout<<"Time taken: "<for (int i=0; icout<", ";

}

cout<return 0;

} This algorithm has three versions of matrix-vector multiplication, namely the SIMD version using all YMM registers which handles column number up to the greatest multiple of 64, a similar version using half the registers handling the remaining column number up to the greatest multiple of 32, and a simple loop-based approach catering to the rest of situations.

Compile with:

g++ -O3 -mavx main.cpp -o avxtestRunning avxtest:

$ ./avxtest

Time taken for serial version: 3980

5831.11, 6747, 6506.54, 6451.99, 5929.76, 6637.35,

Time taken for AVX version: 510

5831.11, 6747, 6506.54, 6451.99, 5929.76, 6637.35,As seen from the timing, using AVX resulted in nearly 8x speed up, which is expected, as each instruction is able to multiply 8 floats in a row. On the contrary, the serial multiplication algorithm, even under maximum optimization settings, was not automatically vectorized by gcc.

原文地址: https://thinkingandcomputing.com/2014/02/28/using-avx-instructions-in-matrix-multiplication/